Quelita, Chalatenango

I was raised in a Catholic home, daily prayers, mass on Sundays, and all the traditional rituals. I never really reflected or paid much attention to what any of it meant. You imitate what other people do at church and you memorize words repeating them over and over. As a kid, I’d prefer to stayed home rather than performing my best behavior just to avoid getting spanked or my ears pulled. The only person that never went to church was my grandfather. My aunts, grandmother, and my mom would justify it saying he was tired or sick.

I remember asking my grandmother why we were forced to go. I told her I also wanted to stayed home with him. Her answer was: “there are some things you can’t understand at your age.” That was how the conversation went.

I don’t remember him ever paying any respect to the priest. He would ignore him if he saw him in the street. This priest had arrived from Italy and turned out to be abusive towards peasants and those who came to church rural areas. He had a reputation of bullying people especially if they were poor.

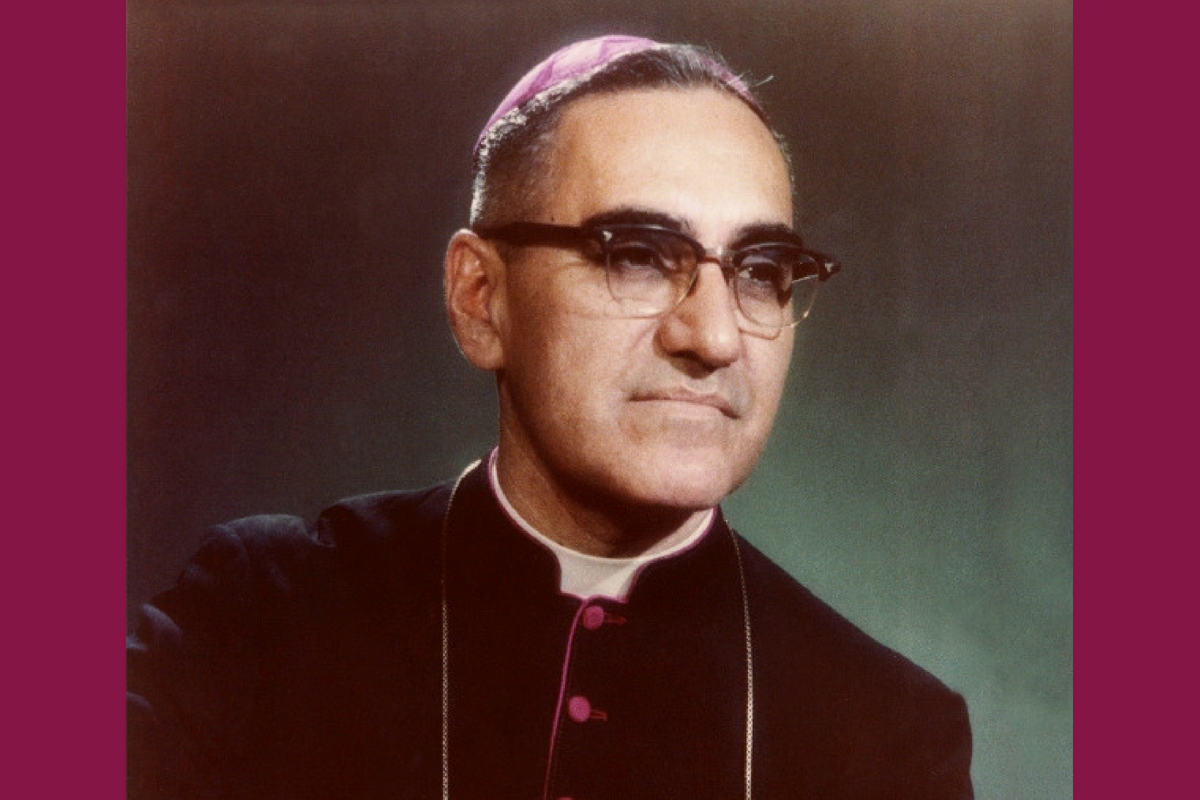

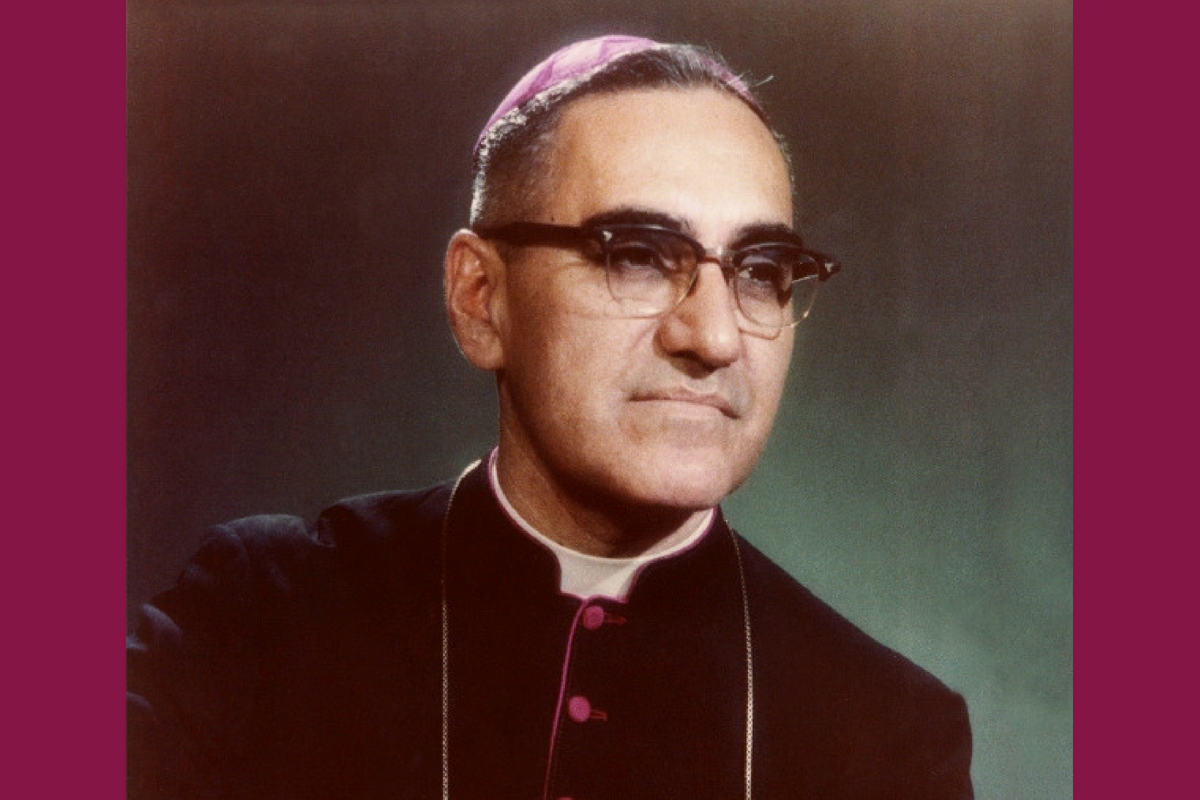

Every morning, my grandfather used to listen to the news from a small radio. One day, he turned up the volume and asked me to pay attention. I got to hear a man who was begging people to stop killing each other. “Who’s that?” I asked. “Just listen carefully,” he responded. When the transmission was over, I learned that this man was Monsignor Romero. I recall my grandfather telling me this was no regular priest and he wasn’t like the one that had been assigned to the hometown where we lived. My grandfather didn’t believe politicians. He used to say they were also a bunch of liars and that even thought some could have good intentions, at the end money always corrupted them forgetting why they were there in the first place. This Romero guy, he said, was more like Christ and it was the type of people he believed in: “The prick you go see every Sunday is like a dictator and is a piece of shit. You need to learn how to see the difference. You don’t owe any respect to him.”

That same year Monsignor was murdered. My grandfather told us that his death was not going to be in vain. He didn’t know how or when but he said this assassination was going to change the history of El Salvador. There were days after this happened that my grandfather didn’t speak. He was more attentive to the radio than ever absorbing every word and sound coming from it. Things were really bad… injustice everywhere…

When my grandfather was on his death bed years later and grasping for what were going to be his last breaths, he told me some things that are resonating today as if it was yesterday: “Stay alert with people who give gifts to buy friendship, trust and sympathy, teach your daughter that mother nature has to be respected because she is sacred, she feeds us and keeps us alive, and you make sure you follow teachings like the ones left by Monsignor Romero.”

Today, I feel my grandfather’s presence more than ever. He was a peasant and a man with a conscious. My Salvadoran heart rejoices knowing he is also celebrating the universal legacy of a man whose actions have left most Salvadorans knowing that love is real and is worth fighting for. ¡Que viva Monseñor Romero!

***

For more Stories From El Salvador, visit their site here. If you want to share your own story, contact them here. You can follow the group on Instagram @storiesfromelsalvador or on Facebook.