TIJUANA — “¿Me compras mi dinero?” a little boy asked, holding his food plate. After he said it a few times to no avail, he pulled out some bills from his pocket. It was Honduran currency. He could not use it to buy anything, and he was asking to exchange money for a currency that could be used in Tijuana near the U.S. port of entry.

A boy asks to buy his money, Honduran currency, so he can get U.S. or Mexican currency to buy things needed. (Photo by Francisco Lozano/Latino Rebels)

18-year-old Luis was hit by a tear gas canister on Sunday at the Chaparral border crossing in Tijuana. He got a head wound that required 12 stitches. (Photo by Francisco Lozano/Latino Rebels)

Migrants living in the streets of Tijuana walk past a hotel to go to local store to buy goods needed. (Photo by Francisco Lozano/Latino Rebels)

The immigrants are basically homeless and staying at the Benito Juárez shelter, a sports field that local officials and humanitarian groups have turned into a tent city. The overflow crowd stays in the streets, in makeshift tents.

Migrant men sit on a barricade near the encampment as night settles in. (Photo by Francisco Lozano/Latino Rebels)

An aid worker uses a mask to deter the foul smell of human feces in the encampment. (Photo by Francisco Lozano/Latino Rebels)

(Photo by Francisco Lozano/Latino Rebels)

A little kid runs of joy after him and his mother are given a ration of food by the Mexican Navy. (Photo by Francisco Lozano/Latino Rebels)

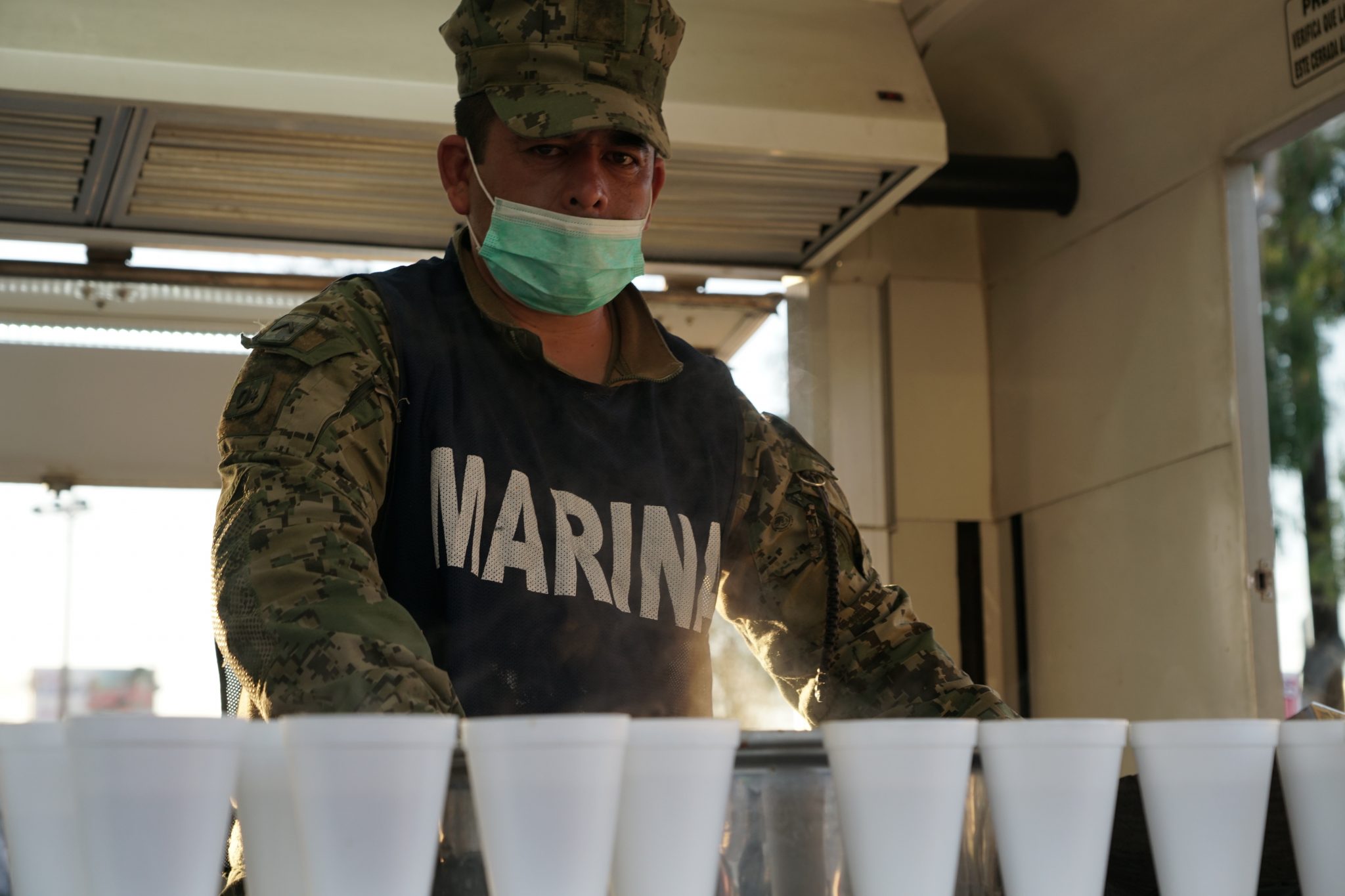

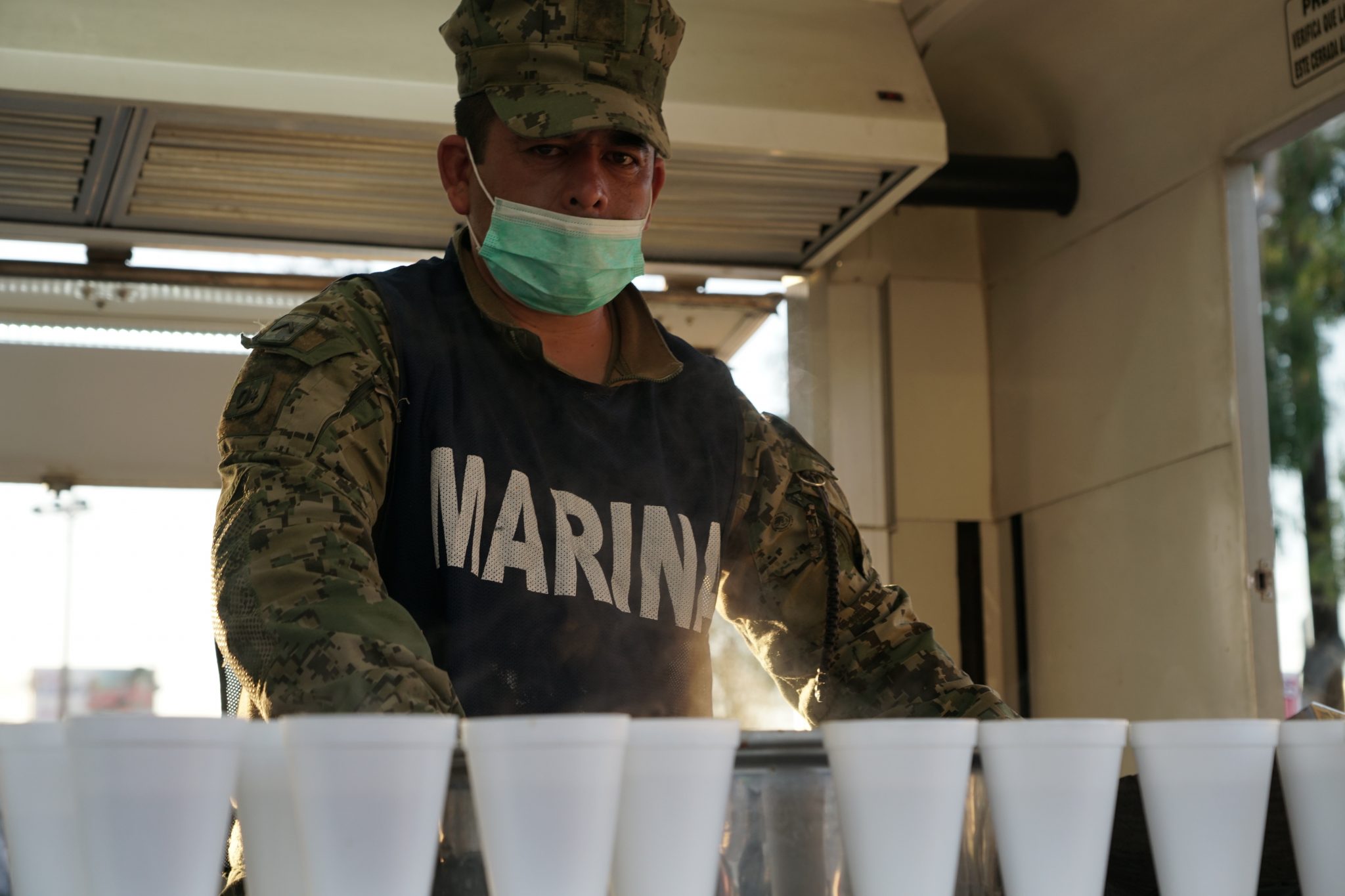

A member of the Mexican Navy serves hot drinks at dusk to asylum seekers. (Photo by Francisco Lozano/Latino Rebels)

A child eating candy. (Photo by Francisco Lozano/Latino Rebels)

To bring some relief, people drive up and drop off clothing and other goods.

Women in children line up during supper rationing at the encampment in Tijuana, Mexico near the U.S. border. (Photo by Francisco Lozano/Latino Rebels)

Migrant mother feeds instant noodle soup to her two young girls. (Photo by Francisco Lozano/Latino Rebels)

La Güera brings temporary joy and a melancholic feeling to the migrants. (Photo by Francisco Lozano/Latino Rebels)

“La Guera” sings a tune protesting the Honduran government after a heated and tearful speech. (Photo by Francisco Lozano/Latino Rebels)

A young mother of three breastfeed her youngest. She chose to remain anonymous in case she gets sent back for fear of her life. (Photo by Francisco Lozano/Latino Rebels)

A tired migrant woman sits on the sidewalk with thank you signs above her in the streets outside the Tijuana encampment near the US border on Monday. (Photo by Francisco Lozano/Latino Rebels)

Many blame the U.S. intervention in the region through decades of civil unrest and revolutions as the cause of the instability, pushing mass migration from the 1980’s to the present. The U.S. supported right-wing regimes in El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, and Nicaragua while they committed human rights abuses. Among these crimes were U.S.-trained death squads.

Families seemed wearier now that they are in limbo at the border than they were during their travail through Mexico. Desperation and stress can be seen in the faces of women and children as they wonder why they are not being allowed to seek much-needed asylum.