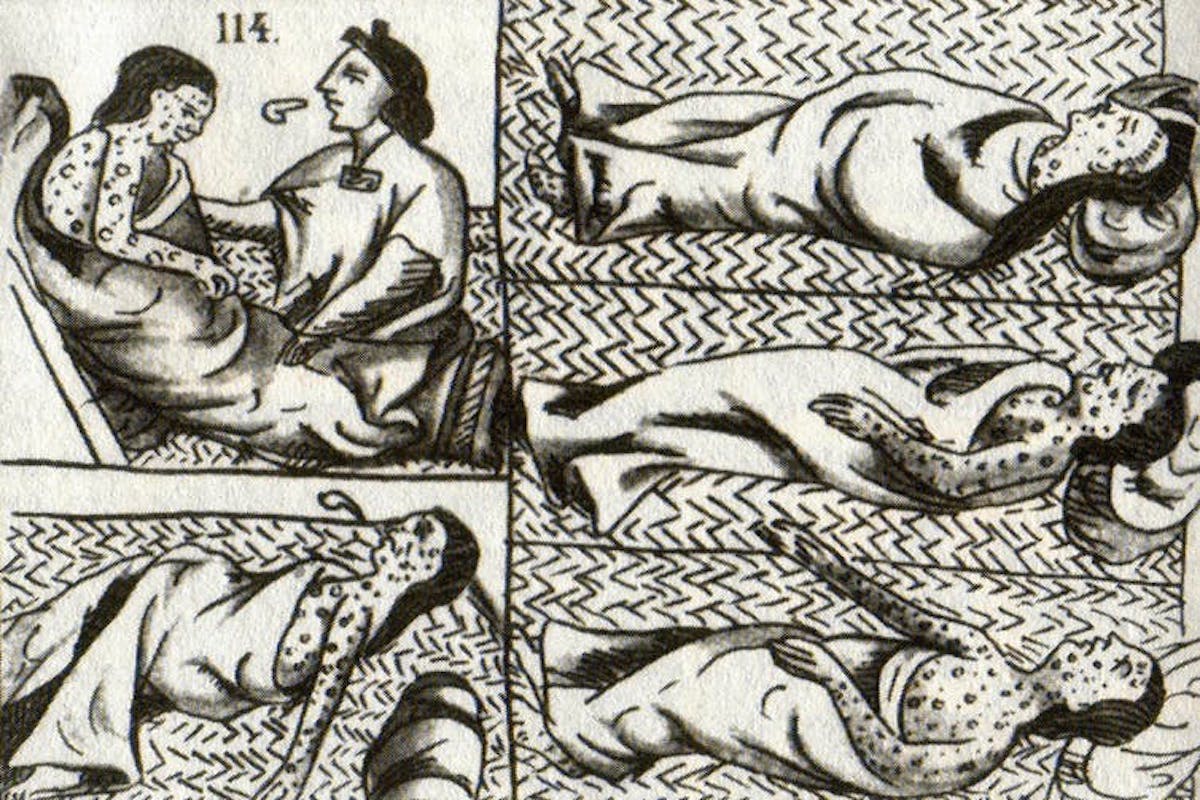

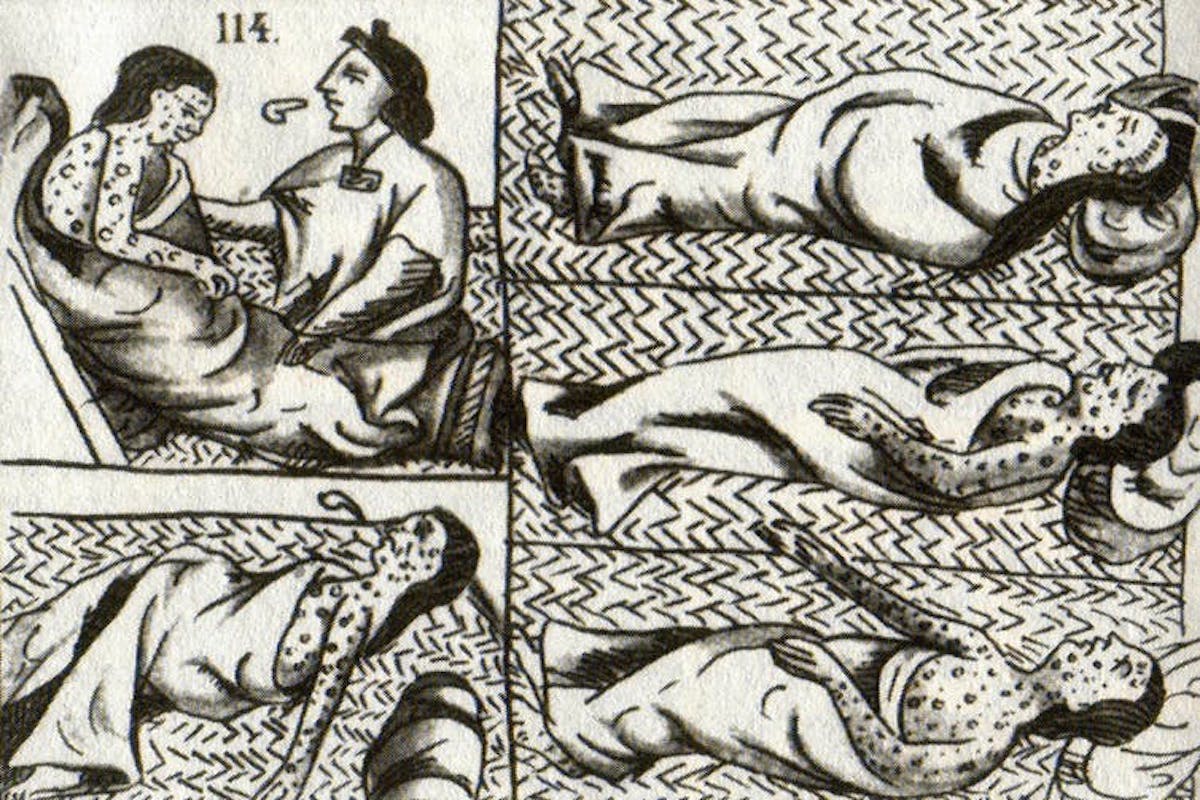

A 16th-century Aztec drawing of smallpox victims.

By Richard Gunderman, Indiana University

Recent outbreaks in the U.S. have drawn attention to the dangers of measles. The Democratic Republic of Congo is fighting a deadly outbreak of Ebola that has killed hundreds.

Epidemics are nothing new, of course. And some widespread infectious diseases have profoundly changed the course of human history.

Five hundred years ago, in February of 1519, the Spaniard Hernán Cortés set sail from Cuba to explore and colonize Aztec civilization in the Mexican interior. Within just two years, Aztec ruler Montezuma was dead, the capital city of Tenochtitlan was captured and Cortés had claimed the Aztec empire for Spain. Spanish weaponry and tactics played a role, but most of the destruction was wrought by epidemics of European diseases.

Conquest of the Aztec Empire

After helping conquer Cuba for the Spanish, Cortés was commissioned to lead an expedition to the mainland. When his small fleet landed, he ordered his ships scuttled, eliminating any possibility of retreat and conveying the depth of his resolve.

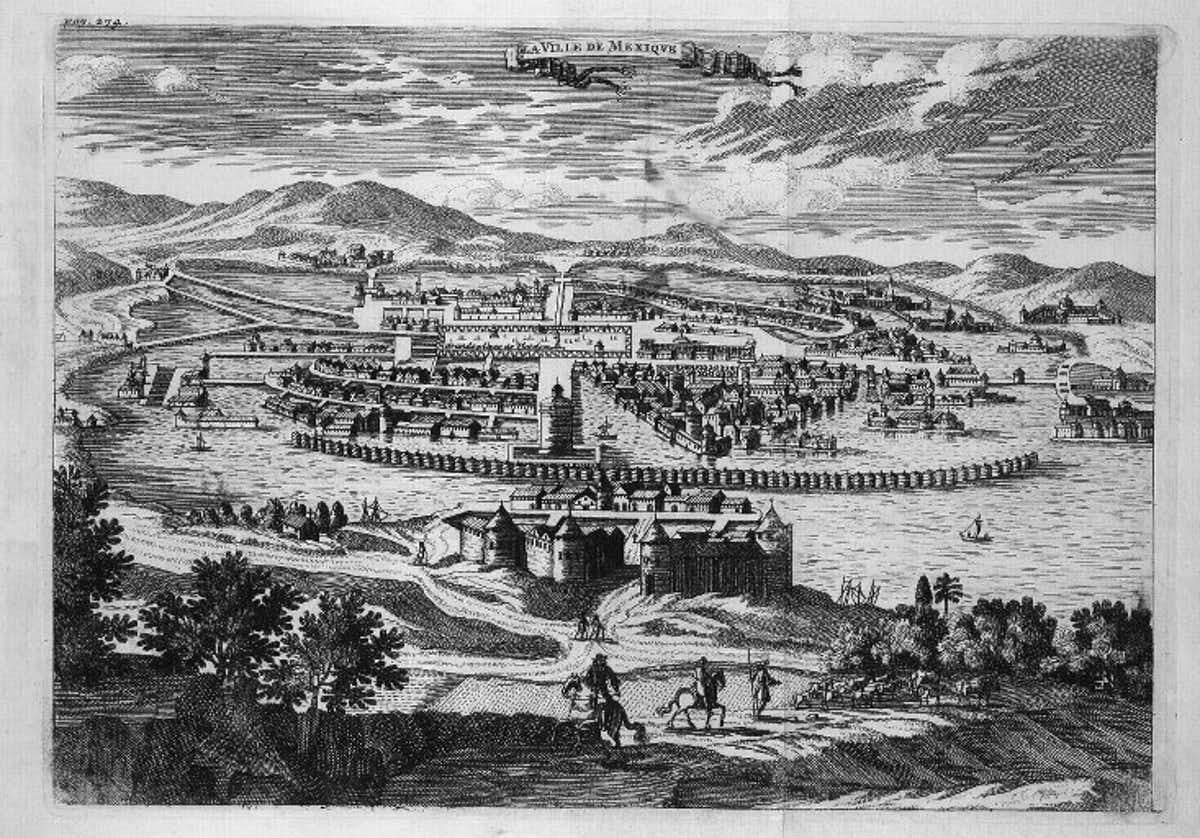

Cortés with his 500 men then headed into the Mexican interior. This region was home to the Aztec civilization, an empire of an estimated 16 million people at this time. Through a system of conquest and tribute, the Aztecs had established the great island city of Tenochtitlan in Lake Texcoco that ruled over an area of about 80,000 square miles.

Discovering widespread resentment toward the capital city and its ruler, Cortés formed alliances with many locals. Though vastly outnumbered, he and a small force marched on Tenochtitlan, where Montezuma received them with honor. In turn, Cortés took Montezuma prisoner.

It took Cortés two years, but he finally conquered the Aztec capital in August 1521. His ally in this fight was the European germs he and his men unwittingly brought with them.

Cortés’ Microscopic Secret Weapon

Although Cortés was a skilled leader, he and his force of perhaps a thousand Spaniards and indigenous allies would not have been able to overcome a city of 200,000 without help. He got it in the form of a smallpox epidemic that gradually spread inward from the coast of Mexico and decimated the densely populated city of Tenochtitlan in 1520, reducing its population by 40 percent in a single year.

Smallpox is caused by an inhaled virus, which causes fever, vomiting and a rash, soon covering the body with fluid-filled blisters. These turn into scabs which leave scars. Fatal in approximately one-third of cases, another third of those afflicted with the disease typically develop blindness.

The disease existed in ancient times in Egyptian, Indian and Chinese cultures. It remained endemic in human populations for millennia, coming to Europe during the 11th century’s Crusades. When Europeans began to explore and colonize other parts of the world, smallpox traveled with them.

The native people of the Americas, including the Aztecs, were especially vulnerable to smallpox because they’d never been exposed to the virus and thus possessed no natural immunity. No effective anti-viral therapies were available.

Recalling the epidemic, one victim reported:

“The plague lasted for 70 days, striking everywhere in the city and killing a vast number of our people. Sores erupted on our faces, our breasts, our bellies; we were covered with agonizing sores from head to foot.”

A Franciscan monk who accompanied Cortés provided this description:

“As the Indians did not know the remedy of the disease, they died in heaps, like bedbugs. In many places it happened that everyone in a house died, and as it was impossible to bury the great number of dead, they pulled down the houses over them, so that their homes became their tombs.”

Smallpox took its toll on the Aztecs in several ways. First, it killed many of its victims outright, particularly infants and young children. Many other adults were incapacitated by the disease because they were either sick themselves, caring for sick relatives and neighbors, or simply lost the will to resist the Spaniards as they saw disease ravage those around them. Finally, people could no longer tend to their crops, leading to widespread famine, further weakening the immune systems of survivors of the epidemic.

Disease Can Drive Human History

Of course, the Aztecs were not the only indigenous people to suffer from the introduction of European diseases. In addition to North America’s Native American populations, the Mayan and Incan civilizations were also nearly wiped out by smallpox. And other European diseases, such as measles and mumps, also took substantial tolls, altogether reducing some indigenous populations in the new world by 90 percent or more. Recent investigations have suggested that other infectious agents, such as Salmonella —known for causing contemporary outbreaks among pet owners— may have caused additional epidemics.

The ability of smallpox to incapacitate and decimate populations made it an attractive agent for biological warfare. In the 18th century, the British tried to infect Native American populations. One commander wrote, “We gave them two blankets and a handkerchief out of the smallpox hospital. I hope it will have the desired effect.” During World War II, British, American, Japanese and Soviet teams all investigated the possibility of producing a smallpox biological weapon.

Mass vaccination against smallpox got going in the second half of the 1800s. (Everett Historical/Shutterstock.com)

Happily, worldwide vaccination efforts have been successful, and the last naturally occurring case of the disease was diagnosed in 1977. The final case occurred in 1978, when a photographer died of the disease, prompting the scientist whose research she was covering to take his own life.

Many great encounters in world history, including Cortés’s clash with the Aztec empire, had less to do with weaponry, tactics and strategy than with the ravages of disease. Nations that suppose they can secure themselves strictly through investments in military spending should study history—time and time again the course of events has been definitively altered by disease outbreaks. Microbes too small to be seen by the naked eye can render ineffectual even the mightiest machinery of war.![]()

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.