Louisiana’s refineries require the kind of oil Venezuela produces to operate properly. AP Photo/Gerald Herbert

By Eric Smith, Tulane University

U.S. sanctions against Venezuela’s state-owned oil and gas company, along with some government officials and executives, are intended to put pressure on the government headed by Nicolás Maduro.

As the interim director of the Tulane Energy Institute, which tracks energy markets and provides forecasts, and someone with 35 years of oil industry experience, I’m certain that they will also reverberate in this country too—especially in Louisiana, where the oil and gas industry is among the state’s biggest employers.

Economic Dysfunction

Despite having the world’s biggest petroleum reserves, Venezuela is now functionally bankrupt and wracked by hyperinflation. Even before the sanctions against Petróleos de Venezuela, the state-owned company known as PDVSA, its crude production was rapidly declining.

Since the late president Hugo Chávez’s election in 1998, followed by Maduro’s rise to power in 2013, the Venezuelan government has effectively destroyed the country’s political institutions, as well as its petroleum-based economy. Oil production has declined by two-thirds, dropping from about 3 million barrels per day in 2000 to around 1.2 million barrels per day in January 2019.

During this long decline, Venezuela collected payments in advance from some of its biggest customers, and therefore cannot collect the revenue now that it would otherwise be obtaining from oil production. Thanks to this practice, it actually doesn’t earn any hard currency from much of the crude that it does export.

Instead, these export earnings actually pay off cash advances from China, Russia and Repsol, the Spanish energy company.

Refineries located along the U.S. Gulf Coast in Louisiana and Texas were just about Venezuela’s last source of hard currency. That came to a halt when the Trump administration slapped sanctions on PDVSA in late January 2019.

Crude Quality

You might think that Venezuela could just find new markets for its oil, but that is harder than it may sound.

Venezuelan crude is heavy and sour, meaning it is extremely dense and contains a high percentage of sulfur. Globally, most refineries process light sweet crude into gasoline, jet fuel, diesel and other fuels and products. Only specialized “complex” refineries can handle the dense petroleum produced in Venezuela and remove its unwanted sulfur.

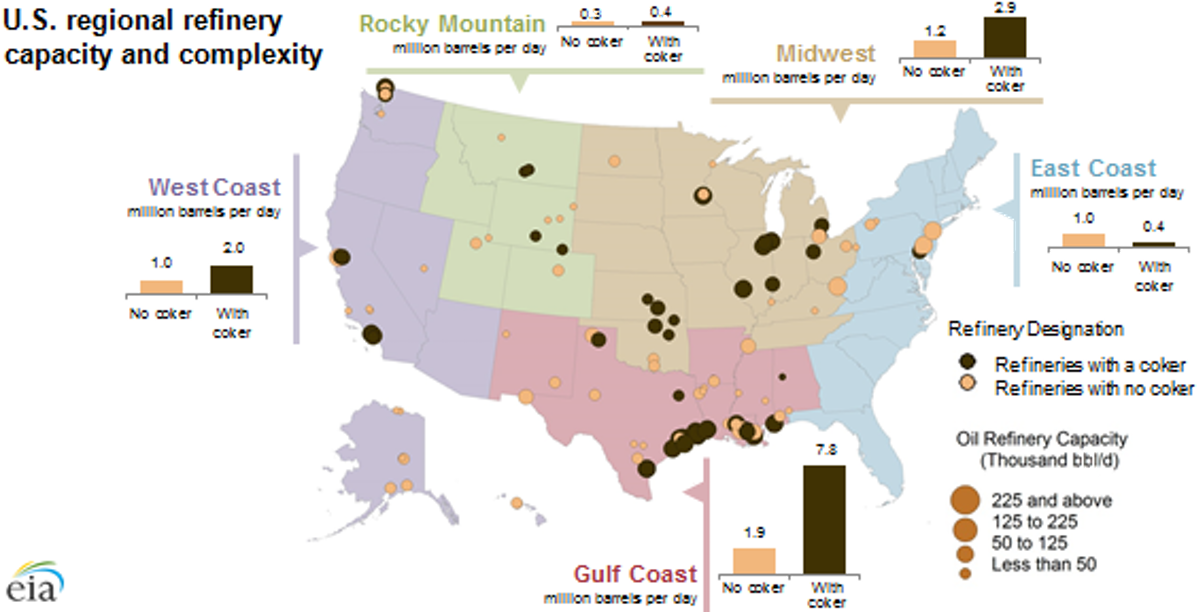

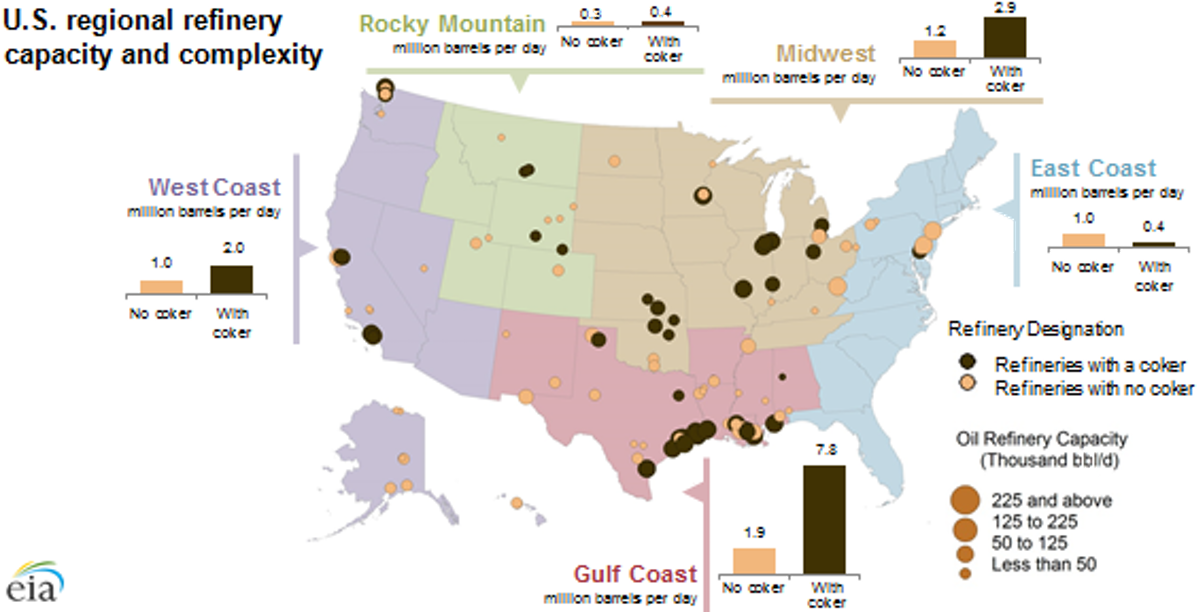

More than half of U.S. refinery capacity is “complex,” meaning it requires at least some heavy crude oil to operate properly. Nearly all Gulf Coast refineries are complex. (U.S. Energy Information Administration)

The U.S. refineries that can do this are mainly located along the Gulf Coast, in the Midwest and in California. Most of the rest are located in China and India.

Complex refineries cost about 50 percent more to build. They are also more expensive to operate. They can compete, however, because they use crude from sources like Venezuela that costs less than most crude oil.

Complex Refineries

Although U.S. oil production is rising, the domestic industry still needs to import heavy crude to keep the complex refineries operating efficiently. As of early 2019, 90 percent of U.S. imports were heavy crude. Countries that export this heavy petroleum include Mexico, Canada, Colombia, Ecuador, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Nigeria and Iran.

Based on their proximity, Canada and Mexico should be good sources for U.S. refiners. However, due to delays in the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline and other pipelines that may eventually run from the northern border to the Gulf Coast, there’s no easy way to replace the blocked shipments from Venezuela.

While Canada is shipping more heavy crude by rail, this approach is much more expensive. It costs about $20 per barrel to ship heavy crude from Canada by rail, versus an estimated $12.50 per barrel via pipelines.

Mexico’s challenge is different. Its heavy crude production has been declining for years. Mexico now imports light crude, as well as gasoline and other refined products from the U.S..

Russia and Saudi Arabia

Another factor is that Saudi Arabia and Russia are cutting their oil production, especially heavy sour crude, as part of an effort to shore up crude prices. Canada is curtailing heavy oil production as well.

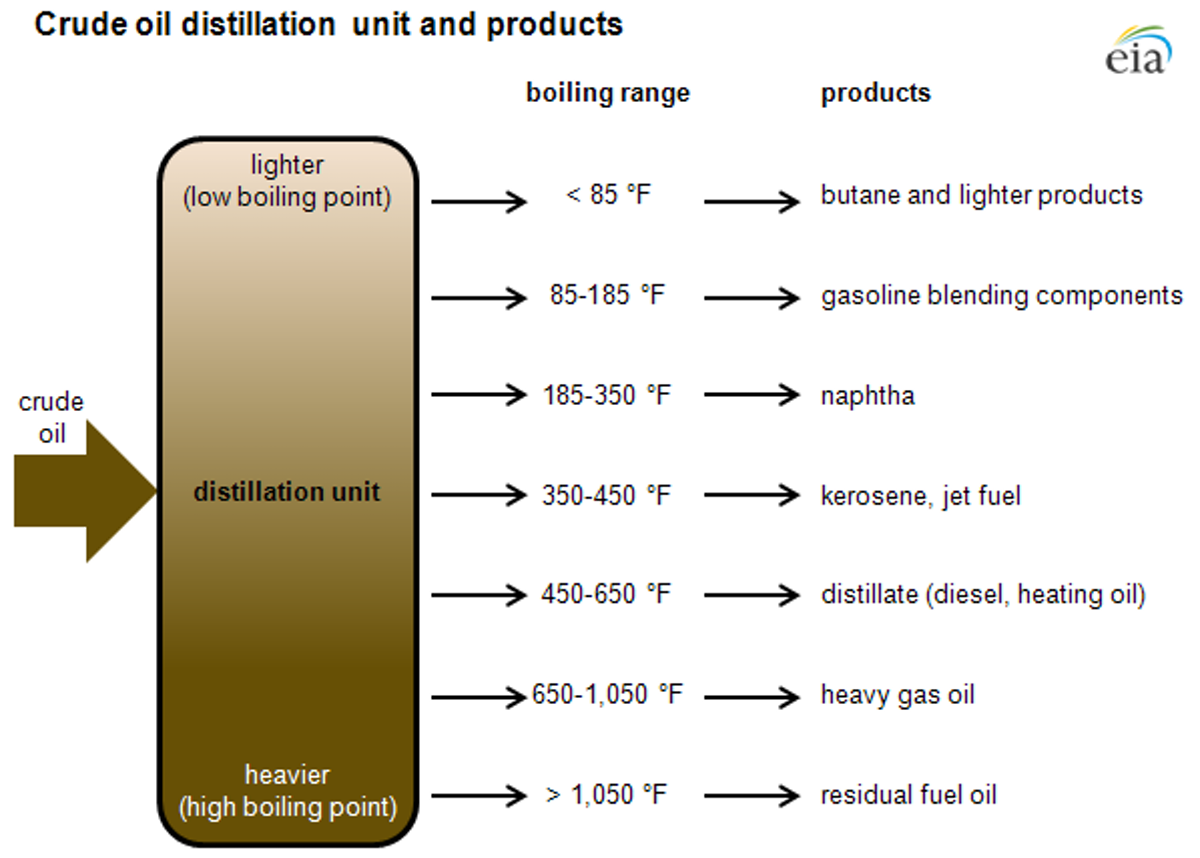

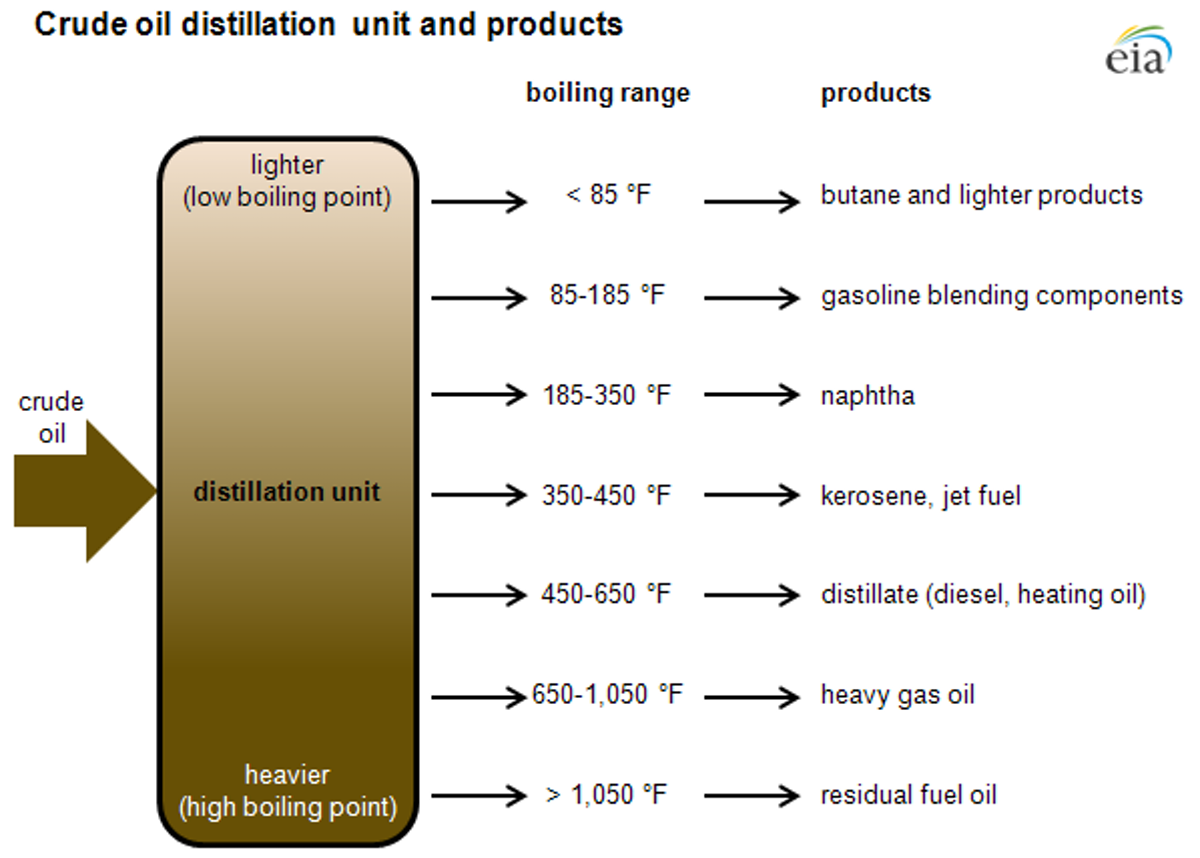

It may sound reasonable for the U.S. to simply substitute its own light sweet crude for imported heavy sour crude. But the crude distillation units at complex refineries like those in Louisiana were not designed to use ever higher percentages of light sweet crude.

These refineries require approximately 30 percent heavy crude to operate optimally. At a minimum, the Gulf Coast region needs something like 3.1 million barrels of heavy sour crude per day.

The 563,000 of barrels per day the U.S. was buying from Venezuela in November 2018 only represented 2.8 percent of the roughly 20 million barrels of crude it consumed. But those imports represented a bigger share of the heavy oil the U.S. used: 17 percent, according to my calculations.

Without that supply, Gulf Coast refineries can only reduce throughput and shut down much of their idle sulfur removal capacity.

High Stakes for Some States

Shutting off heavy crude from Venezuela to Gulf Coast refineries would reduce the production of heavier distillates, such as heating oil, marine fuel oil and diesel.

Heavier crude must be distilled at higher temperatures, which yields diesel, fuel oil and other products. (U.S. Energy Information Administration)

Jet fuel and gasoline won’t be as affected because these products can be produced from any refinery capable of processing abundant domestic light sweet crude.

I would expect U.S. exports of diesel and heavier distillates to decline as a result, particularly shipments to Latin America and to Europe. After that, domestic supplies to the states supplied by Gulf Coast refineries could be hit as well.

Prices for diesel and fuel oil are likely to rise once supplies are constrained, which could occur quickly because U.S. refineries have little capacity to spare.

Even if U.S. refineries do eventually replace Venezuelan oil, the odds are that crude will come from farther away and cost more. That would, in turn, make diesel cost more, increasing the cost to consumers for everything from food to furniture and flat-screen TVs.

This would happen not just in Louisiana, but in communities far away, as long as the delivery trucks, rail cars and vessels involved have diesel engines. The disruption would illustrate the way that U.S. sanctions intended to apply pressure on other countries can also take a toll on Americans.![]()

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.