San Juan seen from the municipality of Gurabo. 98 percent of Puerto Rico is designated as an Opportunity Zone. (Photo by Sebastián Márquez Vélez)

By Joel Cintrón Arbasetti

SAN JUAN, PUERTO RICO — Modesta Irizarry did not know that her town, Loíza, a municipality on the north coast of Puerto Rico, was designated as an “opportunity zone.” In the neighborhood of Salud, Mayagüez, on the island’s west side, Orlando Serrano had not heard that his community is also under the same category. So is almost 98% of Puerto Rico.

Opportunity zones form part of President Donald Trump’s tax reform, which reduces from 37.5% to 20% the tax rate paid by funds that invest in these “low-income communities.” Proposed legislation at the local level that enables the federal program on the island also exempts investors from Puerto Rico and abroad from paying construction excise taxes, while reducing 50% of municipal license fees during a 15 year period.

“We are trying right now to understand the opportunity zones,” said Roberto Thomas, a community organizer from Bahía de Jobos, in southern Puerto Rico, between the towns of Salinas and Guayama.

Community leaders Irizarry, Serrano and Roberto Thomas told the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI) that their communities have not had access to information about opportunity zones.

Dozens of investors and businesspeople, meanwhile, have had the opportunity to orient themselves and listen from government officials, who tout the program’s benefits in various conferences and forums.

State governments designated 25% of qualifying areas as opportunity zones. An exception from Congress allowed nearly 98% of Puerto Rico to be declared an opportunity zone, including Vieques, Culebra and Isla de Mona. Under the special case, certain areas became opportunity zones despite not qualifying under the census’ “low income community” definition.

Tracy Hadden, senior data scientist at the Center for Real Estate & Urban Analysis at George Washington University, said he designation of almost 98% of Puerto Rico as an opportunity zone was “an extraordinary situation” unseen elsewhere in the United States. In an interview with the CPI, she noted that Puerto Rico is especially vulnerable to climate change: it is a Caribbean island exposed to hurricanes and sea level rise.

“Opportunity zones were really designated without thought of that…. If people drove less and consume less land, those two things will slow climate change. Because consuming less land leaves more land available for carbon sequestration and driving less emits less greenhouse gases. Sea level rise and extreme weather is already happening. For example, Red Hook [a neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York] had been designated as opportunity zone. Some models say the main street of Red Hook is going to be underwater in 15 years,” said Hadden, who coauthored a study on opportunity zones for Smart Growth America.

A bill to establish the framework for opportunity zones on the island remains stuck in the Puerto Rico Legislature since November. The Senate approved it, but failed to agree on the amendments made by the House.

Since December 18, the CPI has requested an interview with House Speaker Carlos “Johnny” Méndez. Despite multiple follow-up efforts with his press officer for three months, and even a visit to his office, the lawmaker refused to talk about this matter.

Rep. Antonio Soto, chairman of the House Treasury, Budget and PROMESA Committee, told CPI that a conference committee is currently discussing the bill, namely the “definitions of credit” and “the committee” that will evaluate the projects proposed for these opportunity zones. Soto did not want to give details about the concerns over these two areas of the legislative bill.

On his way out of the Puerto Rico Convention Center following a closed-door meeting among majority lawmakers last Wednesday, Méndez assured “there is already an agreement” over the opportunity zone bill. “[The bill] was discussed [during the meeting]. Maybe it is going to be approved next week,” he said when asked by CPI.

From left to right: Senate President Thomas Rivera Schatz, Governor Ricardo Rosselló, and House Speaker Carlos “Johnny” Méndez at the press conference for the Multisectoral Working Group to Mitigate Climate Change (Courtesy of La Fortaleza)

The proposed legislation lacks mechanisms to ensure that municipalities will benefit from it or that communities will be protected from the impact of large-scale investments or integrated into the economic development process it promises, the CPI found.

“The local bill eliminates all traditional compensation mechanisms, exempts you from paying construction taxes and 50% of municipal licences for 15 years. By exempting these two things, the municipality receives nothing or very little in benefit from the investment being made,” warned Pedro Cardona, a planner and former vice president of the Puerto Rico Planning Board, the entity tasked with the island’s official macroeconomic indicators.

“These municipal license fees are made to compensate. That is: you have this elite development or such, but it contributes to the municipality’s educational system, road improvements, so that everyone can enjoy the benefit of having that investment [project]. When you eliminate that, the proportion totally tilts toward the particular development and not the collective,” he added.

Cardona argued on the little benefit that municipalities designated as opportunity zones could receive versus the burden they will receive during the initial process of development or redevelopment projects.

Pedro Cardona questioned the benefits of the bill that turns almost the entire country into an Opportunity Zone. (Photo by Sin Comillas)

“You are going to have some impact on the municipal water infrastructure, on roads… it has an impact on a lot of things. And then you do not get any benefit, or very little benefit,” added Cardona, who teaches a course on urban theory at University of Puerto Rico’s School of Architecture.

Cayey mayor Rolando Ortiz noted that municipal executives have not been consulted on the opportunity zone bill.

“We have not been consulted and this type of measure is confiscatory. When it comes to encouraging economic activity to the detriment of municipalities, it is not correct. The central government has abandoned municipal infrastructure and when it legislates at the expense of municipal revenue, in times when the government has taken resources away from municipalities, that goes against us,” said Ortiz, who ended in February his tenure as president of the Puerto Rico Mayors Association.

He admitted that he did not know about opportunity zones nor its proposed legislation, yet considered that it is “a genuine effort to activate the economy, which is supposed to have long-term benefits and not everything has to be negative. In other jurisdictions, [the incentive] has had a positive long-term impact. But the [municipal license fee payment and construction taxes] should not be reduced so much, nor it should be reducing both.”

Officials Fail to Prioritize Community Integration

The intent of the federal opportunity zone legislation is to encourage economic development in disadvantaged communities. While states designate opportunity zones in areas that qualify as a low-income community, Puerto Rico’s also include non-low-income areas, leading to the 98% coverage figure.

Rep. Soto believes that no investor “will invest in areas where there is no return on investment. In depressed areas, it would not be worth it because they have no return on investment. A hotel will not be built in that area. Maybe something related to housing or an elderly home, whatever the Permit Office deems fit.”

Ceiba’s coast, on the east of the island. (Photo by Sebastián Márquez Vélez)

On the integration of municipalities and communities to the development process, the lawmaker said that “it depends on the investor’s interest and the zone planning so both can be harmonizes.”

Since the construction of the Ciudadela housing complex in Santurce, for instance, “the whole street has improved and there have been no displacements,” Soto told the CPI.

Still, there were displacements in Santurce. Ciudadela’s current location, with apartments that cost between $128,000 and $335,000, was home to the San Mateo neighborhood. Its residents were evicted, and their houses demolished in 2005, backed by the government and the local Housing Department.

“Municipalities can submit comments to the [Priority Projects in Opportunity Zones] Committee,” Rep. Soto said.

The “Priority Projects in Opportunity Zones Committee” will be ascribed to the governor’s office. The government chief financial officer and former chief of staff, Raúl Maldonado, will preside over the group that would further comprise Chief Investment Officer Gerardo Portela and Financial Advisory & Fiscal Agency Authority (AAFAF) Executive Director Christian Sobrino. “The Governor may appoint additional members to the Committee to meet specific requests,” the bill reads.

From the governor’s office, Maldonado led the inclusion of Puerto Rico as an opportunity zone while he was chief of staff. When the CPI asked how communities will be protected and included in the proposed developments, he said that a “community summit” would be held.

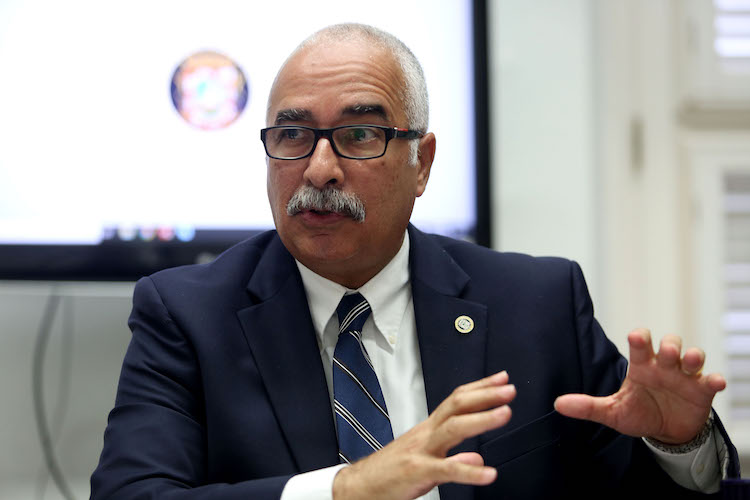

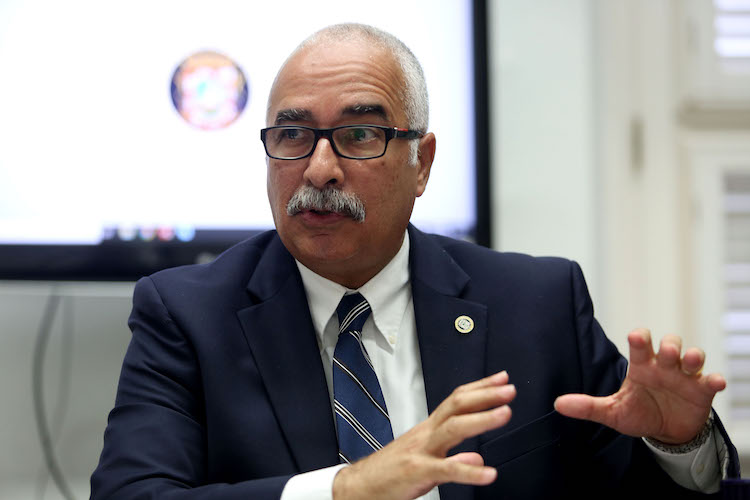

Raúl Maldonado, Puerto Rico’s Chief Financial Officer, led the efforts for the designation of Puerto Rico as an Opportunity Zone. (Photo by Gabriel López Albarrán | Center for Investigative Journalism)

“We will be soon at a conference, a community summit. where we will attend the 736 communities that exist in Puerto Rico and the 336 public housing developments, explaining to community leaders how they can create opportunity zones. Because, for example, if you want to open a place to store food for a community, that qualifies,” Maldonado explained. He added that seminars with community leaders and students would also be held.

Contrary to what the CFO stated, opportunity zones would not be the main topic to be discussed at the community summit, but rather the recovery of communities affected by Hurricane María, three community leaders told CPI.

“[Opportunity zones] is not the central issue, but it was an issue that we were going to try to include,” said Hector Albertorio, director of the governor’s Third Sector and Faith-Based Organizations Office, which is one of the summit’s coordinators.

On Tuesday, the Puerto Rico government is holding the 2019 Opportunity Zones Summit at the Convention Center, aimed at explaining the legislation the benefits of opportunity zones to investors. According to the English-only press release issued by the government, participants include Gov. Rosselló, Portela, Puerto Rico Federal Affairs Administration Director Carlos Mercader, U.S. Treasurer Jovita Carranza and Daniel Kowalski, an advisor U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin.

Six months ago, Maldonado and Portela traveled to the states to present Puerto Rico as an opportunity zone to investment firms. They then met on the island with executives from banks such as Citibank and JP Morgan.

“In the first round of presentations we made on Wall Street, we already had $600 million in just two funds that are already here looking for investment. They already have the money separated in a fund. What we are doing now is, to the Goldman Sachs of life, to the very large firms, we went there and presented to them, and they are now including Puerto Rico in their investment portfolios as one of their most attractive option,” Maldonado told the CPI.

As of February 2019, at least 10 corporations have registered with the local State Department under the “Opportunity Zone Fund” category. This is the type of entity required to tap into the benefits of opportunity zones. Eight of them belong to U.S. investors, mostly associated with Puerto Rico businesspeople. Three of these eight are associated with the same real estate firm: Morgan Reed. Only two corporations appear to be wholly owned by local investors.

“What happens is that the local [investor] will not open [an Opportunity Zone Fund corporation] until local legislation is enacted. The greatest benefit for locals is that they have the same tax benefit as in the U.S., which is a reduced rate on income tax and zero tax on capital gains. So as soon as the legislation passes, you will see that there will be dozens of funds in Puerto Rico. Everyone is following closely,” Maldonado said.

Conferences and Summits for Investors

Investors interested in the tax exemptions offered by opportunity zones held a conference on January 30 at the Vanderbilt Hotel in Condado, organized by Colectivo 360, a real estate firm. A press release issued by the entity referred to opportunity zones as a mechanism to invest in “communities in difficulty.”

Attending the event was Manuel Laboy, Puerto Rico’s economic development secretary.

The local opportunity zones bill does not establish that the tax exemption program is aimed at low-income communities. The 58-page document barely mentions them. The only part that mentions these words is in its preamble, which explains that not only low-income communities were designated as opportunity zones.

“Opportunity zones are definitely a program to promote investment in communities. This is called a community development program. Particularly for economically and socially disadvantaged communities, as the bill states,” Laboy said.

Aerial view of Cantera, one of the sectors of the Communities of Caño Martín Peña. In the background, the Golden Mile in Hato Rey, Puerto Rico’s main financial center. (Photo by Sebastián Márquez Vélez)

The CPI asked how are communities integrated in this process.

“We are at this moment… This type of event is very important to attract a type of investor, because at the end of the day, you have to achieve two things: bring those who want to invest and tie them with the projects. This will eventually make the quality of the project, which will define whether investors are interested in getting into this. And in the definition of the project, that’s where I see a great opportunity to integrate the communities,” Laboy explained.

How?

“Well, that’s not going to happen here because this is to attract investors,” Laboy replied.

Will it happen later?

“Well, in my case, in the case of the Economic Development and Commerce Department [DDEC], each project has a strategy. Roosevelt Roads, for example, which is not currently chosen as an opportunity zone, we do want to include it and we are meeting with the association that represents the communities of Ceiba and Naguabo. That is an example of what I want to do with the rest of the projects that we are pushing.”

Admission to the event cost $500 for general audience and $3,000 to sit at the “sponsor table,” which was reserved for executives of firms such as KPMG, Kevane Grant Thornton, Somera Road, Reality Realty and BMA Group. The room was packed and, according to one speaker, 30% of attendees were investors from abroad. Gov. Rosselló delivered the keynote speech.

The event organized by the Collective 360 called for investors interested in the tax exemptions offered by the Law of Zones of Opportunities. (Photo by Joel Cintrón Arbasetti | Center for Investigative Journalism)

Alberto Bacó, a former DDEC secretary, attended the event, although this time on the investors’ side.

The CPI asked Bacó whether he is interested in opening a fund to invest in opportunity zone projects.

“Yes, one of my personal projects is a redevelopment and hospitality industry fund. I believe in the visitor economy, I believe that part of Puerto Rico’s future lies in doubling the tourism industry. So I’m raising a fund. I already have investors for the fund, which is going to be called the Puerto Rico Rediscovery and Redevelopment Fund.”

The local legislative bill has no mechanism to integrate or protect communities declared as opportunity zones, the CPI told Bacó.

“On that, I understand that discussion should be promoted,” he said.

How?

“Well, to publicly talk about how to avoid the negatives that normally… To do it through legislation is very difficult because then people do not invest. You want them to invest, but you also want the negative effects of gentrification not to occur. So you have to promote dialogue, you have to promote forums like this and bring that point and discuss it,” Bacó explained.

During the forum, however, nobody discussed this issue.