Central American migrants crossing Suchiate River on makeshift boats. (Iván Francisco Porraz, Author provided)

By Stacey Wilson-Forsberg, Wilfrid Laurier University and Iván Francisco Porraz Gómez, ECOSUR

The day we arrive in Ciudad Hidalgo, Chiapas, the southern Mexican state that borders Guatemala, all is quiet. A violent confrontation had occurred just the day before: Central American migrants, mostly from Honduras, had thrown rocks at Mexican migration officials who attempted to stop their entry into Mexico over the international bridge. Many of the migrants hope their final destination will be a better life in the United States.

As we approach the town, we chance upon a small caravan of about 30 men, women and children walking along the road in the scorching sun. They are in rough shape and we decide not to take photos today. We don’t want to compromise their privacy. Dignity is one of the few things these people have left.

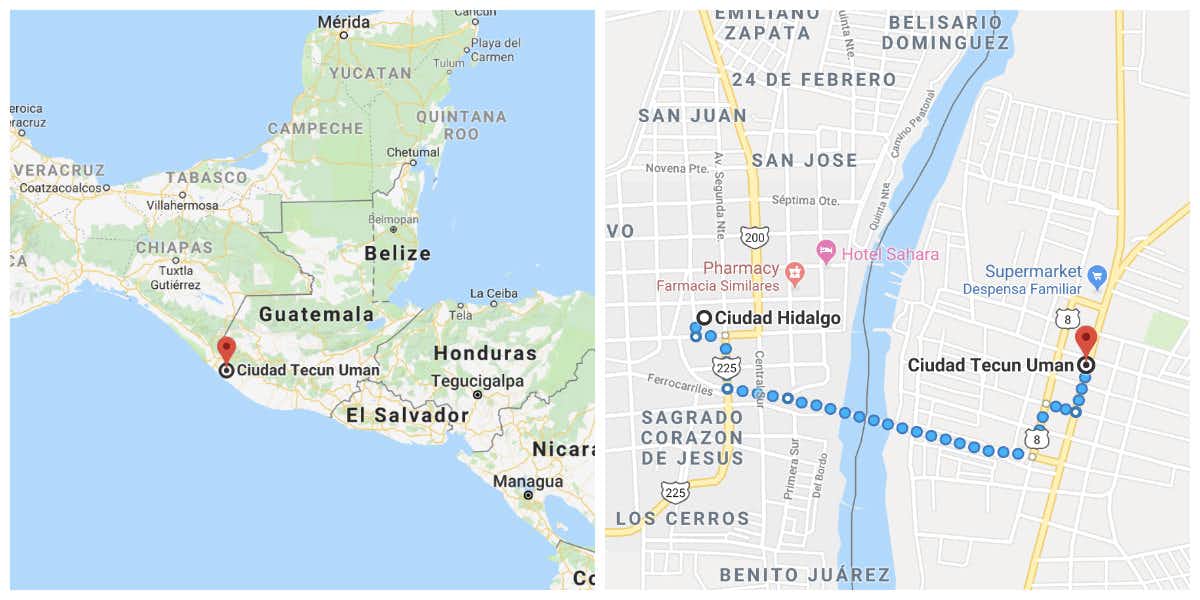

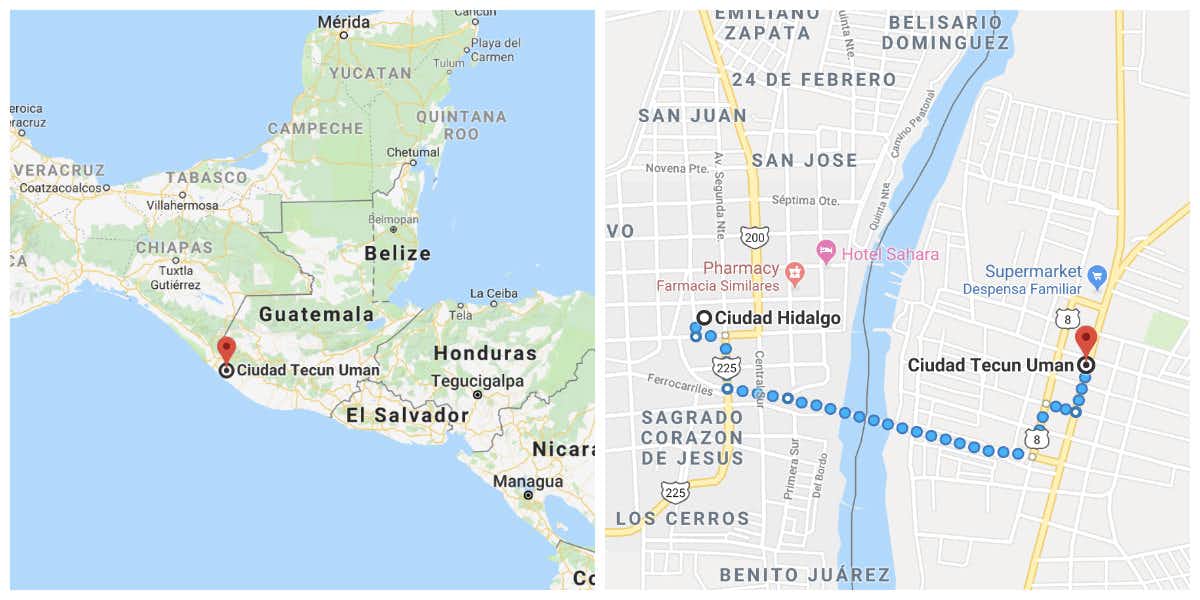

Left is a map of the area detailed and right is the border crossing. (Google Maps)

U.S. President Donald Trump’s insistence on building a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border to keep out “illegal” migrants receives constant media coverage. However, outsiders to the procession know little about the frontera sur, the 871-kilometer stretch of land between southern Mexico and Guatemala that is the gateway to North America.

We are two researchers: one in human rights from Canada and the other in social anthropology from Mexico. We visited the border region last month to observe daily life and to gather information with the hope that these details will help us to change the media narrative that often dehumanizes Central American migrants.

Since October 2018, thousands of people have entered Mexico in several “caravans.” Most of them cross the Suchiate River that cuts through Tecun Uman, Guatemala and Ciudad Hidalgo, Mexico and continue their journey through Mexican territory.

The small caravan we witness is accompanied by Mexican federal police and several government migration vans. We are unsure if the vans are empty or full of detained people. We later learn that the federal police are leading the caravan away from the larger city of Tapachula (near Ciudad Hidalgo) and out of the state of Chiapas.

Central American migrants wait to be processed by Mexican migration officials on the international bridge connecting Mexico and Guatemala. (Iván Francisco Porraz, Author provided)

The migrants will find Good Samaritans who will give them water, tortillas and diapers along their journey. However, patience is wearing thin toward their burgeoning presence in the centre of Tapachula.

The migrants are nameless people: “nobodies” with little choice but to continue the journey northward to Mexico City and ultimately to the U.S. border. They travel in groups because there is safety in numbers. The region is notorious for criminal gangs and human trafficking.

As migrant caravans become commonplace, life carries on along the Suchiate River. It has become a place of permanent mobility.

What Will Happen When You Go Home?

The Honduran exodus is the result of a fateful combination of unemployment, environmental degradation and generalized violence.

The Honduran government does little to improve the deeply embedded poverty and inequality that foster these conditions. A long history of sustained U.S. intervention in the region has aggravated the situation and accelerated the human exodus..

This “mixed migration” phenomenon does not easily fit into the narrow definitions of the 1951 UN Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. The migrants have international protection needs, but they are also seeking to improve their economic situation. Many hope they will reunite with family members in the U.S. Nevertheless, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) asks the question: “What will happen to you if you go home?” The vast majority respond that their lives are in grave danger.

Humanitarian Visas

Day-to-day survival is the goal of this vulnerable population.

Applying for refugee status in Mexico is the best option for survival in the long term. However, the country’s refugee determination process is backlogged and unpredictable.

A humanitarian visa allowing the migrants to live and work in Mexico for one year is fast but temporary. For desperate people, one year seems like a lifetime. In their situation, they can’t think ahead.

It seems that the Mexican government’s response to the caravans has been reactive rather than pro-active. The result is semi-controlled chaos.

One day the Hondurans enter Mexican territory legally with humanitarian visas and the next day they are denied visas and barred entry. Those who take their chances by swimming across the river are detained and deported.

Life Goes On

Migration from Central America is a historical and socio-economic reality. But the constant movement of border residents back and forth to buy and sell goods also adds to the frenetic environment of the frontera sur.

At the shore of the shallow river, we watch merchandise crossing from Guatemala to Mexico on small wooden planks balanced on rubber tire tubes. Men in waist-deep water pull the makeshift boats and guide them with long poles.

A young woman prepares Salvadoran pupusas on the strip of land between Mexico and Guatemala. (Stacey Wilson-Forsberg, Author provided)

Shipments of mangoes, corn flour and feminine hygiene products in purple boxes are neatly piled along the shore in an effort to avoid paying customs duties.

At the quieter forested border crossing of Talisman, Chiapas, a long queue of smashed cars awaits entry. The cars are towed over 3,000 kilometers from the U.S. border city of El Paso to Chiapas. They are repaired in Guatemala and sold throughout Central America.

On the strip of land between Mexico and Guatemala is an improvised pupusa eatery. We ask the young woman preparing our lunch whether the pupusas are Honduran or Salvadoran—an ongoing debate around here. “Salvadoran,” she replies. The young woman identifies as Salvadoran, although she was born in Mexico and has never actually been to El Salvador, a mere 12-hour drive from the border.

People will continue to flee Honduras and the other Central American countries. High numbers will walk over Mexico’s southern border in large and small caravans. They will stop to rest and attempt to make money by selling fruit and candy or begging, and then they will continue their journey northward.

As they pass through, life goes on in the hot, humid and hilly stretches of land where tumultuous Central America and the poorest part of Mexico meet.![]()

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.