Alex (featured in the film) drinks water on a hot day in Texas. (Photo by Moyo Oyelola)

Current anti-immigrant policies can instill fear and discourage people from making the journey to the United States. Look no further than family separations still happening at the border or President Trump’s recent pitch to Congress to declare “national emergency” in hopes of funding his U.S./Mexico border wall, which the Senate later blocked. The message is clear: the United States seems and feels like a hostile place for immigrants.

The rhetoric by the Trump administration has been normalized to the extent that it bled over to the mainstream, and into people’s daily lives. Downright racists attacks in public spaces —such AS Aaron Schlossberg’s (a.k.a racist NYC midtown lawyer) threats to call ICE for hearing people speak Spanish or the other xenophobic tirade coming from Jill Kronenberger, in which she told the manager of a Mexican restaurant in Parkersburg, West Virginia, Sergio Budar, to “get the f*ck out” of her country for hearing him speak Spanish— are a manifestation of bigots feeling empowered to spout hateful language.

When those acts of transgression become almost too commonplace, the public goes to its leaders in search of guidance or just reassurance. But when some prominent politicians fail to condemn white supremacy and acknowledge the dangers underprivileged communities face, people are at a standstill.

For that reason, art that focuses on the plight of marginalized people gains greater significance. We observe things with a different lens—we see everything more critically and with more urgency. Directed by Chelsea Hernandez, Building the American Dream (which recently had its World Premiere at this year’s SXSW) is a documentary that follows three immigrant families in Texas. They find themselves in a system stifled by abuse of power and labor in favor of economic gain.

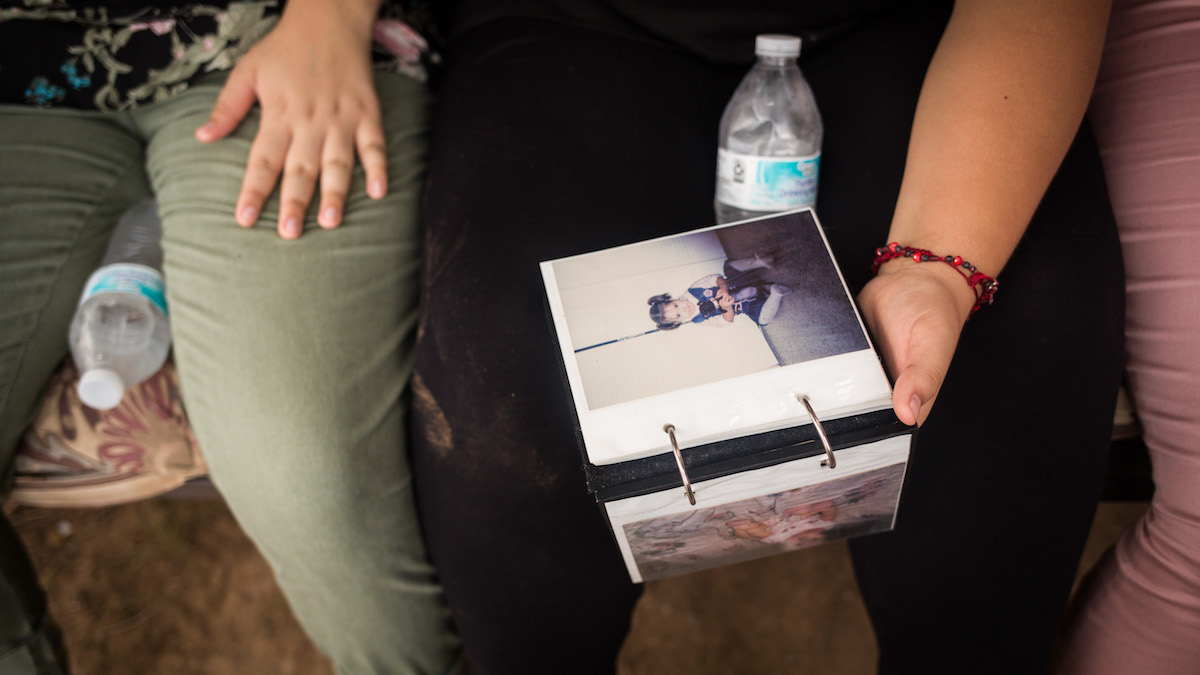

The film features the Granillo family. The patriarch Gustavo starts off by admitting that people approach the loss of a loved one in different ways; his son Roendy Granillo died at the age of 25 at a construction site. You could “destroy” everything that reminds you of that person or you could choose to venerate your loved one, hoping to keep their memories alive, in the most tangible ways possible, as the father says. In the family’s case, they choose the latter. There are countless photographs of their deceased son all over the house.

Looking through a family photo album, Roendy’s mother reminisces on life when her son was alive. (Photo by Moyo Oyelola)

A commendable decision by the director is to humanize the young man. We learn that Roendy had other interests that didn’t reduce him to solely being a construction worker. The parents show us a painting he had finished prior to his tragic death. Despite no formal training, he was a talented painter, and viewed as special.

As a way to honor their son’s death, the family decides to fully campaign on a “Rest Break” ordinance, a safety measure which would allow construction workers an official break during working hours—there’s no state or federal law that requires construction companies to give their workers one.

The documentary perfectly captures the excruciating and nerve-racking process of American bureaucracy. During a council hearing, members of the Granillo family express their concerns about the well-being of immigrant workers, about what message it sends if the city just profits off of people’s labor without providing protections and rights. We witness different council members for and against the ordinance. Some show genuine empathy while others offer a less convincing performance and finish it off by beating around the bush as to why they can’t support the safety measure in favor of workers. Despite strong opposition among members, the Dallas City Council agrees to vote on the “Rest Break” ordinance at the next hearing. After all the back-and-forth, the Granillos leave hopeful that their son’s death will not be in vain.

The Granillo family gather for a group photo in Dallas, Texas. (Photo by Moyo Oyelola)

In another part of the city, we meet Salvadoran electrician power couple Claudia and Alex. They work well on projects together and have been doing it for many years now. At first glance, they seem happy, but like many immigrant workers, they were exploited for their labor without receiving the compensation they deserved. When they demanded to have their wages paid, the superintendent decided to call the cops on them, claiming theft. Until this day, the couple is still owed around $11k.

Aside from that, Claudia has to check in with ICE every three months—she risks deportation every time she shows up. This is when it hits: the prospect of family separation is not exclusive to the border with incoming migrants, but even with people who have lived and raised families in this country for years.

Sometimes you don’t have to experience labor abuse first hand to get involved in shaping the narrative. The documentary profiles DACA recipient Christian as he attempts to educate other migrant workers of their rights to prevent another death like his father’s, who died while working at a construction site. He meets immigrants and is inquisitive about their well-being and overall health. Christian knows that some of them aren’t honest due to fear of retaliation from their bosses. He emphasizes that educating workers of their rights and protections is crucial if they want to combat the rampant abuses.

It’s easy to lose yourself in the stories the film highlights, but if you take a second and pull back, you realize that they represent just a small fraction of immigrants in the state of Texas alone. Through interviews with industry experts, we learn that one-fifth of workers are denied payment, fifty percent of workers are undocumented, fifty percent of close to one million workers are without any kind of protection, and the most disturbing is that every two and a half days a construction worker was dying in the state. Those statistics are hard to process, but serve to educate the public about the life-and-death sentence immigrant workers navigate every day.

There’s a moment early on in the documentary that puts things into perspective. A real estate agent takes us on a luxury apartment tour. Big open spaces, lavish and modern appliances, exciting views overlooking the city. The apartment reflects the mainstream notion of the American Dream, live and in the flesh. And this is the crux of the film. What is the “American Dream?” What do you sacrifice to achieve it? But most importantly, who gets to experience it? What needs to happen in order for you to say “I’ve made it?” Does the dream even exist? And lastly, for whom is it a tangible goal and for whom is it an elusive far-fetched, well, dream?

The “Texas Miracle” is a popular phrase in the state. It basically means that no matter what, Texas always finds a way to thrive. The recent economic boom reinforces that idea. But what the film makes clear is that miracles don’t happen in a vacuum: in Texas, immigrants create the magic, they are the miracle.

***

Luis Luna is Latino Rebels’ arts writer. He tweets from @luarmanyc.