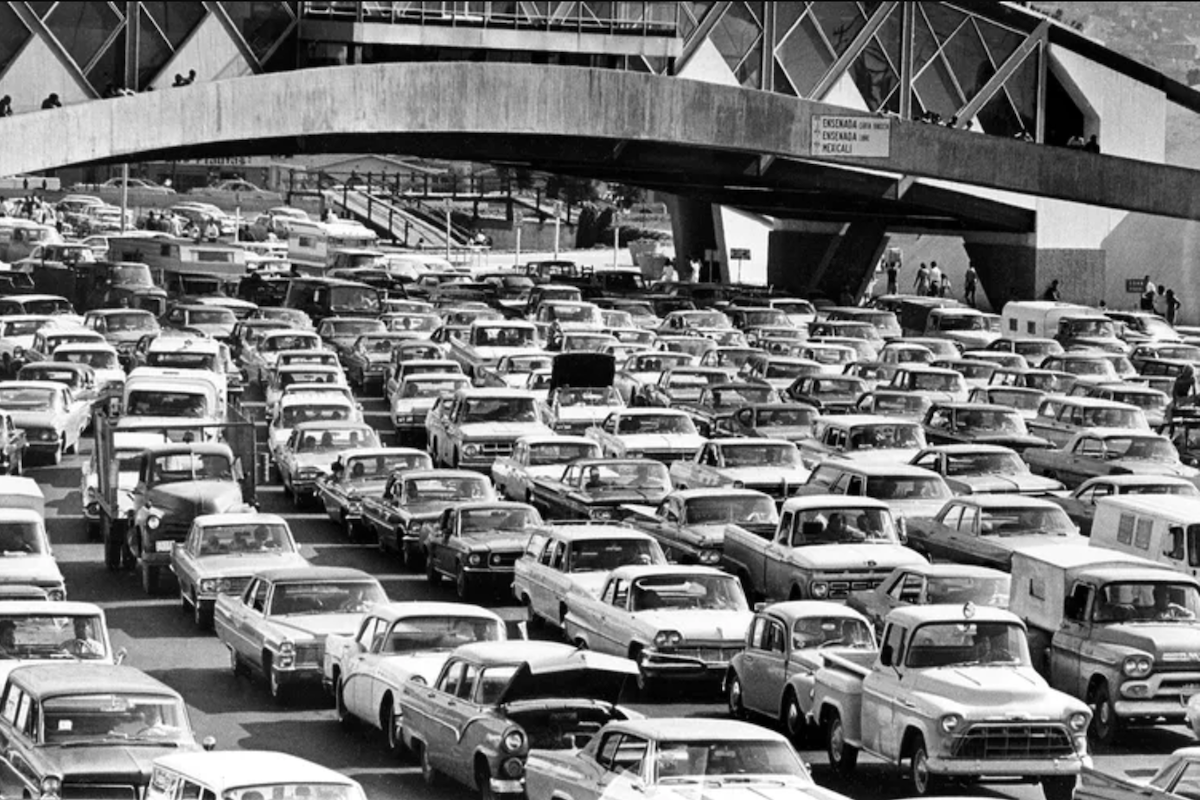

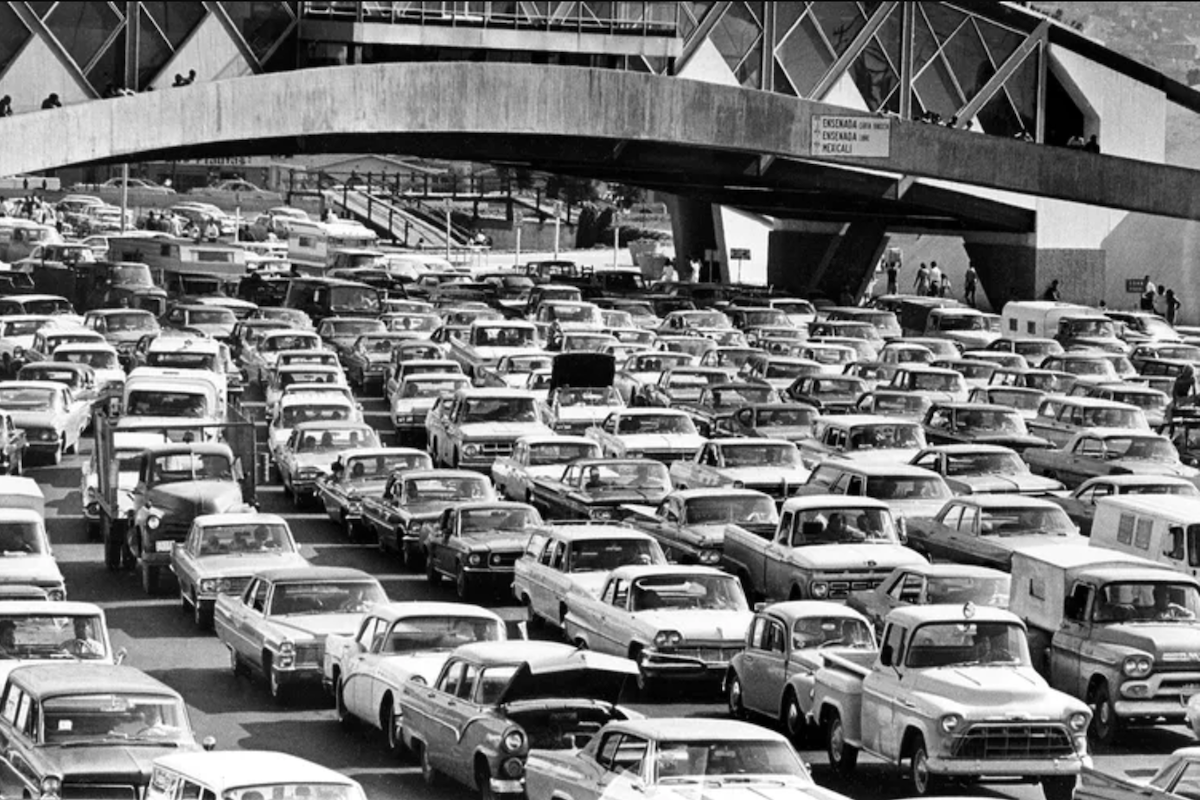

Nixon’s Operation Intercept in 1969 led to massive traffic jams. (AP Photo)

By Aileen Teague, Brown University

Just a week ago, President Donald Trump appeared poised to take the drastic step of closing the U.S.-Mexico border to both trade and travel. He said he wanted to stop the flood of Central American migrants entering the United States but also punish Mexico for failing to do so.

….through their country and our Southern Border. Mexico has for many years made a fortune off of the U.S., far greater than Border Costs. If Mexico doesn’t immediately stop ALL illegal immigration coming into the United States throug our Southern Border, I will be CLOSING…..

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 29, 2019

….the Border, or large sections of the Border, next week. This would be so easy for Mexico to do, but they just take our money and “talk.” Besides, we lose so much money with them, especially when you add in drug trafficking etc.), that the Border closing would be a good thing!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) March 29, 2019

But on April 4, the president backpedaled and instead gave Mexico a year to stop the flow of drugs across the border. If that didn’t happen, he threatened, auto tariffs would be imposed—and the president suggested he might still close the border if that didn’t work.

If Trump ever follows through on his threat and puts up a closed sign at the southern border, it wouldn’t be the first time. Twice in the last half-century, the U.S. has tried to use the border to force Mexico to bend to America’s will. The ruse failed both times.

I studied these incidents while researching for a book on the origins of U.S. drug control policies and militarized policing techniques in Mexico from the 1960s to the 1990s. The history suggests that threats of border closure may be politically useful but are never a real answer to human tragedy.

Operation Intercept

In 1969, President Richard Nixon launched Operation Intercept in hopes of forcing Mexico to collaborate more fully with his administration’s policies to stop the flow of drugs—one of his campaign promises.

Although it technically wasn’t a full border closure, it required customs agents to search every car, truck and bus entering the United States. This caused long delays and a significant drop in economic activity in both countries. Border businesses and politicians begged Nixon to end Operation Intercept.

Meanwhile, Mexican leaders paid lip service to U.S. demands, based on my archival research. They highlighted the progress they had already made in their anti-drug operations and vowed to “continue with increasing intensity.”

Mexico even said it was willing to accept American anti-drug aid, such as aircraft and sophisticated weaponry, in order to help the Nixon administration fight its drug war.

In the end, however, nothing substantial changed. The border reopened after three weeks.

The incident did, however, teach Mexican leaders how to appease similar American demands in the future by using the right “war on drugs” rhetoric.

But in practice, drug control was never a top priority of the Mexican government. And Mexico even used American anti-drug policies to its own advantage. For example, in the 1970s, the country received U.S. financial aid to stem the flow of drugs. It used at least some of the money to suppress domestic political dissent instead.

History Repeats

The war on drugs also inspired President Ronald Reagan’s partial border closure in 1985. Aptly named Operation Intercept II, it suffered a similar fate.

The Mexican authorities were unable to find a kidnapped Drug Enforcement Administration agent, and the White House once again decided to use the border to force them into more vigorous action, closing nine checkpoints.

Ordinary Mexicans saw this border closure as yet another form of “Yankee imperialism.” They wondered how the disappearance of one agent could cause such an uproar when hundreds of Mexicans had been killed as a result of our “war on drugs.” The abducted agent was later found dead.

Although the border was reopened within a matter of days, once again, the shutdown severely hurt the border economy—as well as relations between the two countries.

Border Closings Make Bad Policy

Both versions of Operation Intercept were severely disruptive while failing to motivate any meaningful changes in Mexican policy on drug control, border security or anything else.

Put another way, they showed that it is effectively impossible to close the U.S.-Mexico border, or to severely restrict traffic, for any extended period of time. The economic, social and cultural interdependence of Mexico and the United States is too deep. And U.S. national security depends on strong relations with Mexico.

Trump’s warnings about an “invasion” of Mexican rapists and Central American gang members may appeal to his supporters. His threat to close the border may as well. But, as his advisers apparently pointed out to him, border closings do little more than damage economies and foster resentments. Immigration would dip but hardly stop.

Mexico and the United States are allies, not enemies. The way I see it, pushing Mexico and other nations to do America’s bidding on highly complex problems like drug control and migration simply produces more antagonism while failing to achieve the desired results.![]()

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.