By Nicolás Bedoya

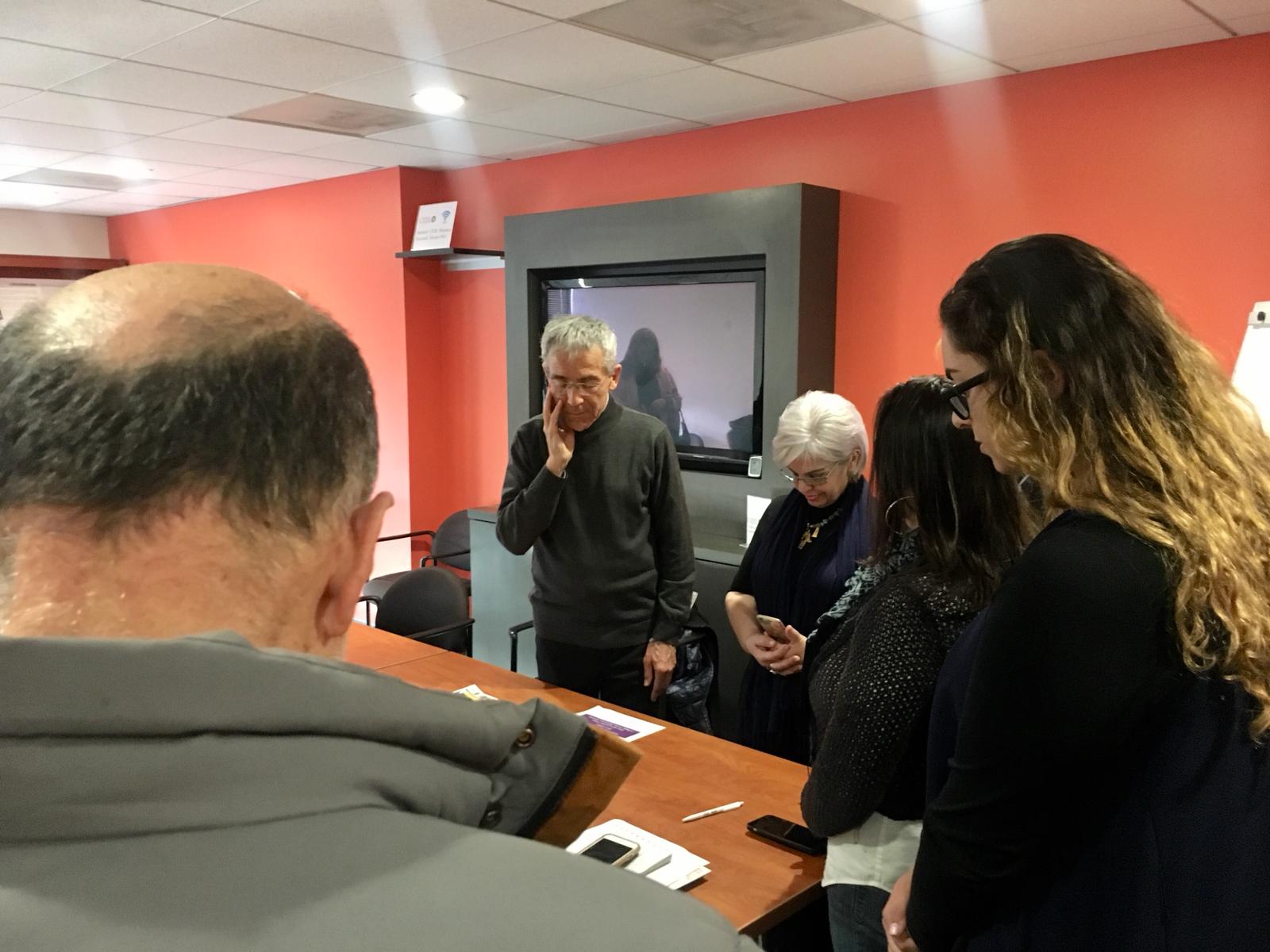

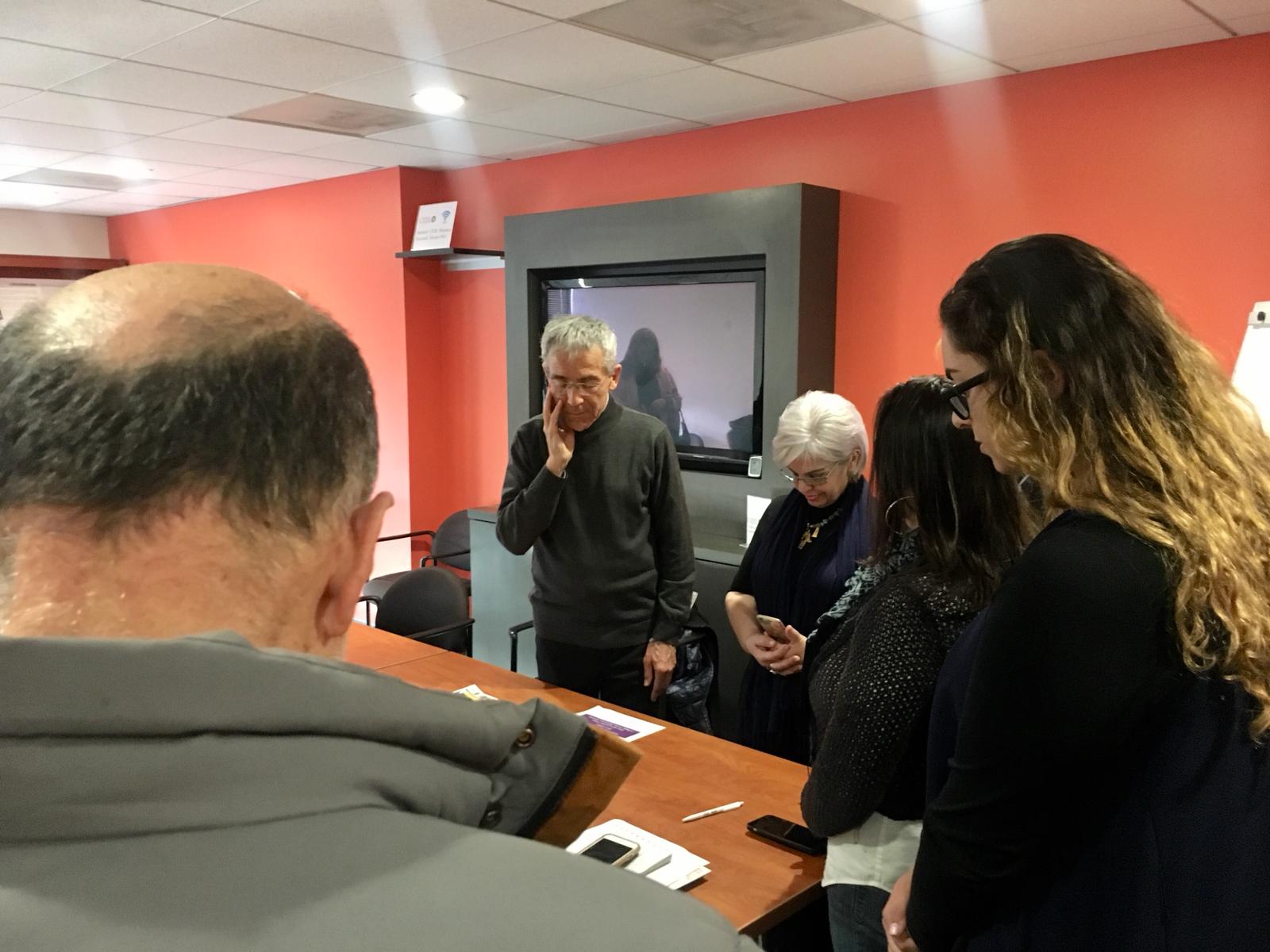

In a small classroom at the City University of New York (CUNY), exiled Colombians gathered to talk with Arancha García del Soto on April 16. Del Soto is part of Colombia’s Commission for Truth Clarification, Peaceful Coexistence and Non-Repetition, also known as the Truth Commission, tasked with piecing together the complex history of the country’s decades-long armed conflict.

Colombian Truth Commission in its EXILE chapter @ CUNY pic.twitter.com/rxSVPXZWET

— aranchagarciadelsoto (@aranchagdelsoto) April 18, 2019

Although there is no reliable statistic, del Soto says there are an estimated 350,000 to 500,000 exiled Colombians as a result of the internal armed conflict, which, despite a peace agreement signed in December 2016, continues to rage. Since the signing of the peace deal, over 450 social leaders have been murdered.

As a result of the historic peace accord with the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), the Colombian government created the Truth Commission to gather the collective and individual memories of the victims of the conflict. It’s the first commission of its kind in the country’s history. The event in New York offered the exile community the chance to contribute their own memories, which have historically been silenced, according to Mary Roldán, a professor of Latin American history at CUNY who has researched the conflict in Colombia.

“The incapacity of people to share their voice and see their story reflected in the official narrative that gets published and reproduced in a country is a way to suppress the lives of others but also marginalize and exclude,” Roldán said.

At the end of its three-year mandate, the Truth Commission must produce a final report that explains what happened during the armed conflict, why it happened, the consequences of the violence and recommendations for ending the cycles of violence.

The commission is led by the Jesuit priest Francisco de Roux, who is well-known for his defense of human rights and work in some of Colombia’s most hostile places. De Roux has witnessed the worst of Colombia’s armed conflict, having buried 27 of his murdered friends and coworkers. Only one member of the commission, Carlos Martín Beristain, was born outside of Colombia. It was Beristain who proposed working with the exile community. He and a team of 40 specialists, including del Soto, are traveling the globe and defining the methodology for the task. After the inauguration of the Truth Commission in November, del Soto and Beristain got straight to work in their native Spain and then traveled to Germany, France, Switzerland, Australia and now the United States to meet with the dispersed exile population. This community often has been overlooked due to the impression in Colombia that they were better off and had more opportunities, but exiled Colombians see it differently.

Francisco de Roux leads a moment of silence before starting a meeting with exiled Colombians in Washington, D.C., in November 2018. (Photo by Nicolás Bedoya)

“In Colombia, leaders are killed, but here in the United States, even though we have freedom of expression, we are killed morally,” Yolanda Naranjo said at the CUNY event.

The pain of leaving their homes and families and uprooting their lives with no or little support has further silenced victims. The Truth Commission hopes its presence in countries with exiled Colombian populations will cultivate the trust necessary for victims to share their painful stories. However, the new Colombian government, headed by President Iván Duque and the Democratic Center governing party, has been openly hostile to the commission. By the time the commission was inaugurated on November 28, 2018, their budget had been reduced by 40%.

“This is an attempt to strangle the commission,” del Soto said.

As a presidential candidate, Duque wrote an op-ed in national newspaper El Colombiano, hinting that he believed the commission was trying to justify the armed rebellion of the FARC. To dispel these accusations, del Soto reiterated several times during the meeting that the commission wants the testimonies of all victims willing to tell their stories, no matter their politics or affiliations with armed groups. Since the Truth Commission is an extrajudicial body, the victims’ testimonies can have no legal repercussions, providing more incentive for victims and victimizers to tell the truth.

“Transitional justice is black and white, but the historical truth is gray,” de Roux said at a meeting with exiled victims in Washington, D.C., in November.

At the meetings held in the United States, exiled journalists, politicians, businessmen and religious and social leaders have answered the commission’s call. Victims of paramilitaries, the national army and guerrillas have attended these initial meetings to hear the mission and methodology of the commission. In many cases, the pain of exile has passed on to the next generation. In Washington, the children of victims attended the meeting instead of their parents, who said they preferred to not reopen wounds.

Del Soto and Beristain have opted for a psychosocial approach to the victims, prioritizing their well-being to avoid re-victimizing them. “Our biggest challenge is in creating that trust and the collective environment necessary to share that pain that is so fragmented, divided and hidden,” del Soto said.

In today’s world where “truths” themselves have become the subject of debates, the work of the commission may seem impossible. But for the dozens of victims and commissioners who meet behind the closed doors of universities, the truth of the conflict is slowly being pieced together.

“Silence kills but you can’t cover up the truth,” del Soto said. “The same way you can exhume bodies, you can also exhume the truth. That is our conviction.”