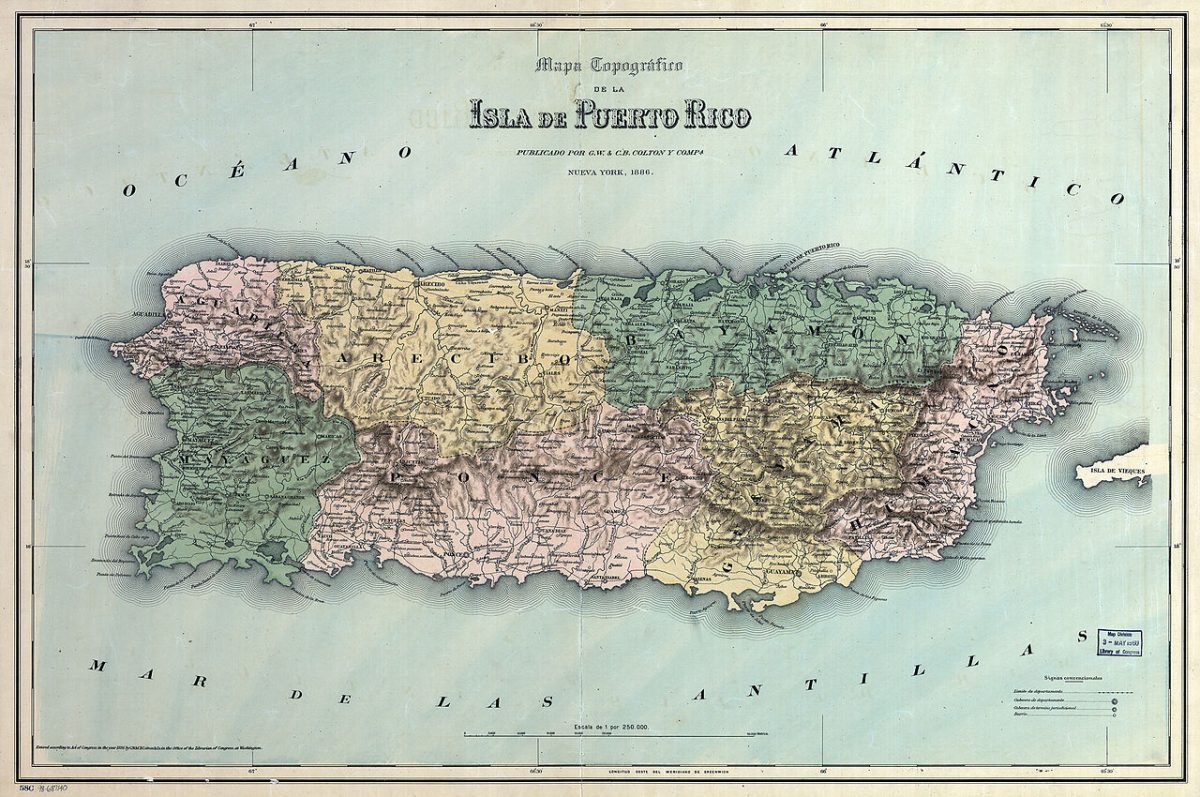

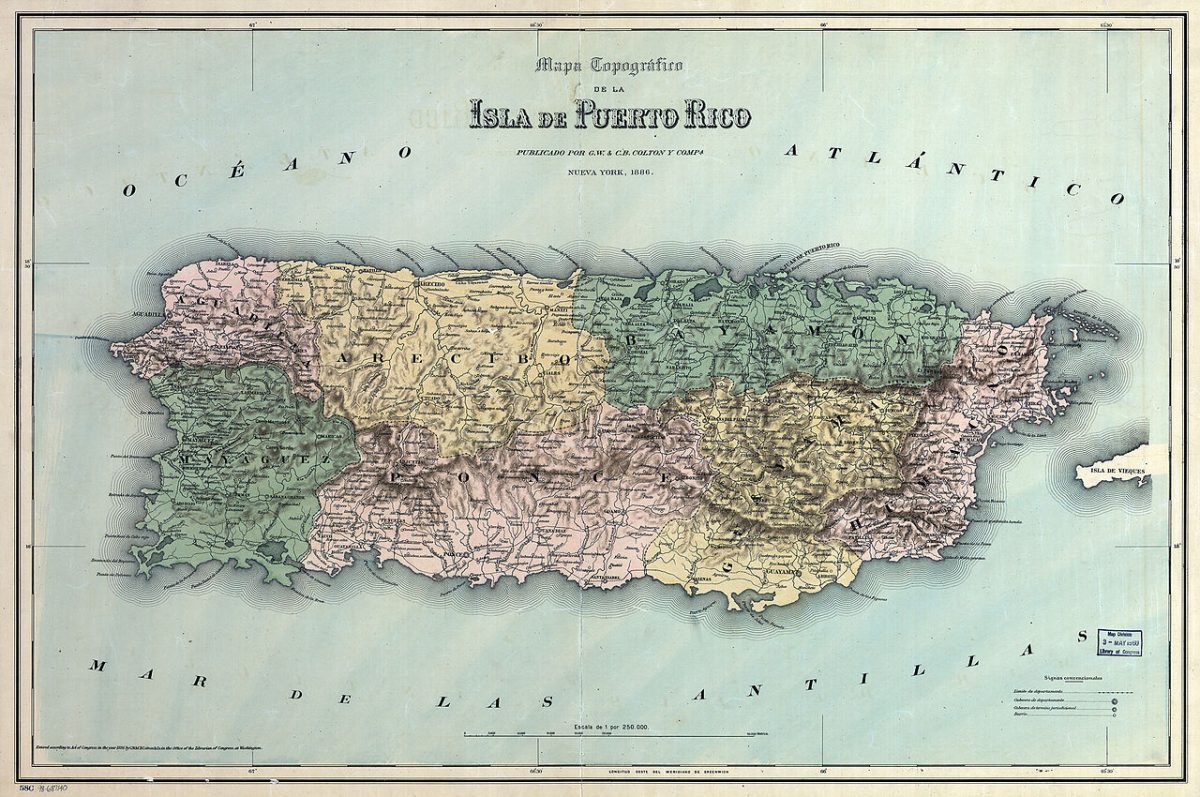

Departments of Puerto Rico under Spanish rule in 1886 (Public Domain)

Editor’s Note: The following article was first published at New York Magazine’s Intelligencer. Puerto Rico’s Centro de Periodismo Investigativo worked with New York Magazine to publish an English version and a Spanish one. The CPI has granted us permission to republish the English version below. Versión en español aquí.

By Andrew Rice and Luis Valentín Ortiz

Since 2016, Puerto Rico has been buffeted by a natural disaster and several overlapping, man-made catastrophes. Its government is bankrupt and owes $74 billion to bondholders: a staggering sum that amounts to 99 percent of the island’s gross national product, or $25,000 for each of its 3 million men, women, and children. It faces a vociferously hostile president, a stalemated and colonial relationship with Congress, entrenched local political dysfunction, and a bunch of angry creditors—most notably, a group of hedge funds that speculate in distressed debt and are fighting for every last penny they think they’re owed.

“I mean, it’s basically a management crisis,” Bertil Chappuis said one afternoon, as we sat at a Cuban luncheonette in San Juan. “Set aside the politics. Set aside policy. Set aside all of that. There was a true management crisis that had come to a head because of the debt.”

Nail, meet hammer: Chappuis is a senior partner at McKinsey & Company, perhaps the world’s most influential management consulting firm. McKinsey prides itself on tackling the world’s most important and intractable problem. Over its century-long existence, the firm —or “The Firm,” as its employees refer to it— has conceived and propagated many of the ideas that now rule American business, which is to say, American life. Its influence can be seen in corporate suites (a disproportionate number of Fortune 500 CEOs are ex-McKinsey consultants) and grocery stores (the bar code is a McKinsey innovation), in banks, universities, and hospitals. All the while, the firm has maintained an air of mystery, seldom disclosing the details of its works, deflecting credit when its efforts are successful, dodging blame when they blow up or inflict pain on those on the receiving end of its efficiencies.

For the last two years, though, Chappuis and the firm have taken on an unusually visible role in Puerto Rico’s contentious and very public bankruptcy process. Under a law Congress passed in 2016, the island’s finances are overseen by a federally appointed board, which hired McKinsey as its “strategic consultant.” Chappuis, in turn, is the firm’s point man. In October, the board issued a 148-page fiscal plan that touches nearly every sector of the Puerto Rican government. Following McKinsey’s guidance, it laid out numerous service reductions, agency consolidations, and “right-sizing” measures—the plan’s euphemism for job cuts.

“This is a historic opportunity to actually reset the game here,” Chappuis declared when we first met in mid-January. Raised in San Juan, he is tall and dark-haired with a regal bearing. His background is in internet technology, and he has scant experience dealing with a governance problem on the scale of Puerto Rico’s. He has never worked as an elected official or a bureaucrat or an economist (but he leads a team of consultants who do have such expertise). What he does possess is an infectious enthusiasm for management science—the much-chronicled “McKinsey Way.” His optimism is unwavering, even as his work and the firm’s role in Puerto Rico seemed imperiled.

Bertil Chappuis

The day after we had coffee, public employees would protest outside the federal courthouse, where the island’s bankruptcy case was being heard. Leaders of police unions were blaming a wave of murders on budget cuts and mismanagement. The critics of the oversight board —or la junta de control, as it is called by people in Puerto Rico who say its powers far exceed oversight— decry both the impact of the cuts and the fact that much of the resulting savings would go to repay creditors, including the hedge funds, many of which bought bonds at a deep discount after Puerto Rico defaulted on its debts.

In D.C., Democrats like presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren were excoriating McKinsey for having “paved the way for many of Puerto Rico’s creditors to receive handsome payouts.” Meanwhile, the Trump administration was maneuvering to cut federal disaster aid to the financially fragile island, a campaign that culminated in April with a Twitter tantrum accusing Puerto Rico’s “grossly incompetent” elected leaders of “foolishly or corruptly” spending the money the territory had already received. Democrats and Republicans in Congress are currently at loggerheads about how much, or how little, relief to offer.

As if that weren’t enough, McKinsey’s involvement in Puerto Rico was complicated by…McKinsey. Over the past year, the firm’s once unimpeachable reputation has been tainted by disclosures stemming from a series of lawsuits and newspaper investigations that reveal its intimate links to bad businesses (the pharmaceutical company that popularized opioids), bad policies (Trump’s immigration crackdown), and bad people (Saudi Arabia’s allegedly murderous Prince Mohammed bin Salman). McKinsey’s core company value, its loyalty to its clients, has been called into question by allegations of double-dealing. Last fall, The New York Times reported that McKinsey had millions invested in Puerto Rican bonds via the firm’s secretive internal hedge fund. McKinsey denied any conflict of interest, saying it was a routine investment that its consultants on the island were unaware of, but at the least the revelations gave McKinsey’s critics more ammunition to claim it was profiting from Puerto Rico’s misery.

Among the many mind-blowing figures in the fiscal plan, one stands out: the $1.5 billion earmarked over the next six years for costs related to the restructuring process itself—more than a billion of which will go to lawyers, bankers, and consultants, McKinsey included. (The firm billed the board more than $72 million through January, and its ongoing contracts total about $3.3 million a month.) The projected overall fees are more than five times what Detroit spent on its $20 billion bankruptcy, previously the largest local-government default in U.S. history, and higher even than the bill for Lehman Brothers, the $613 billion corporate liquidation that nearly destroyed the world economy.

All those fees are being footed by the taxpayers of Puerto Rico, which is far poorer than any U.S. state, with a median household income of less than $20,000 a year. Its economy was shrinking even before the island was devastated by Hurricane María, among the deadliest storms to ever hit U.S. territory. Everywhere in Puerto Rico, whether talking to community organizers or high-level government officials, I heard the refrain: “They’re treating us like guinea pigs.” And they’re right. Puerto Rico is a sort of island laboratory for an experiment in austerity. Although Detroit and a few other cities have gone bust —D.C. in the 1990s, New York in the 1970s— there is currently no legal mechanism for a U.S. state to declare bankruptcy. Yet as baby-boomers retire, many states face debt and pension obligations that may force a reckoning like Puerto Rico’s. Illinois owes $50,000 per taxpayer; New Jersey, $60,000.

2018 meeting of island’s fiscal control board (Photo by Centro de Periodismo Investigativo)

Already the island is an object lesson in what happens when the logic of capitalism overtakes the structure of government. It is an article of faith at McKinsey that the same management theory that makes businesses run more profitably can be applied to further the public interest. “It’s not about cutting costs. It’s about how we deliver the service more productively,” Chappuis said, arguing that the focus on the immediate pain of austerity is simplistic. “The notion of value, of expanding the pie, of doing things better and cheaper —everything that moves a modern economy forward— is missing from the debate.”

Of course, that assumes that what advances the modern economy advances the common good—a proposition currently under siege from both the right and the left. “When things are working correctly, it’s a huge problem,” one young former McKinsey consultant said of the firm. Disgusted with the company’s work with federal law enforcement under Trump, he recently quit and penned a scathing anonymous essay in the leftist journal Current Affairs. “McKinsey is capitalism distilled,” he wrote. “Its advocacy of the primacy of the market has made governments more like businesses and businesses more like vampires.”

***

Capitalism lured Puerto Rico into this calamity; could capitalism lead it back out? It is possible that the most clear-eyed analyst of the island’s history of mismanagement, and the best guide to understanding its future, is the consultant who embodies its present state of tumultuous transformation. Chappuis believes he can help the island pull off an economic miracle because he’s seen one happen there before. When he was growing up, Puerto Rico was considered a model of progressive economic transformation. A government program called Operation Bootstrap, initiated shortly after the Second World War, shifted the territory from plantation-based agriculture toward industrialization. “That led to 25 years of amazing economic growth,” Chappuis said.

By the 1970s, though, the development engine had sputtered out. Like many bright young Puerto Ricans, Chappuis left to attend college, in his case at MIT, and made his life on the mainland. He moved to Palo Alto and joined McKinsey in the mid-1990s, just as the internet economy was lifting off. “I basically started our software practice,” Chappuis said. But he couldn’t stop thinking about Puerto Rico. “It was very frustrating to see everything around me booming and then I’d come back here and everything seemed to be in stasis.” Then stasis turned to crisis.

According to a forensic investigation commissioned by the oversight board, Puerto Rico’s government engaged in a wide variety of destructive borrowing behaviors. Many states have done similarly, but Puerto Rico has a much smaller tax base, and as a territory —without congressional representation or the right to vote for president— it can’t count on the same level of federal support. Puerto Rico’s Medicaid program, for instance, is funded at a much lower rate than the states’. For 30 years, the island used a federal tax break to attract new industries, such as pharmaceuticals, but Congress phased out the subsidy in 2006, sending the economy into a slump. Still, local politicians continued to spend lavishly on crowd-pleasing public works, like a $2 billion San Juan train line than ran just 10 miles. They relied on accounting gimmicks to balance the budget, and when they faced a gap, they borrowed more money. Most citizens were barely aware of what was happening. The debt mounted stealthily like a hidden rot.

Because of Puerto Rico’s quirky territorial status, its bonds offered tax advantages to mainland investors. “Puerto Rico debt was a hot commodity on the bond market,” Chappuis said. “This became an art form in Puerto Rican government: how to carve out revenue streams.” Around five years ago, though, the streams finally ran dry. The island’s credit rating plunged as analysts questioned whether it would have the revenue to service its enormous debt. When Puerto Rico made a desperate issue of $3.5 billion in junk bonds in 2014, warnings in the prospectus suggested a default was imminent. But hedge funds snapped up the bonds anyway, enticed by a loophole in U.S. law that seemed to prevent Puerto Rico from declaring bankruptcy. It looked as if the bondholders could seize tax revenues or assets belonging to the island and no one could stop them.

President Obama and Congress stepped in to give Puerto Rico a measure of legal protection from its creditors. Defying a lobbying campaign by the hedge funds, Congress enacted a law called PROMESA —Spanish for “promise”— that had two main components. First, it allowed the island to seek bankruptcy protection and thus work out its debts in federal court. Second, it created the oversight board to supervise the bankruptcy proceedings and impose fiscal discipline on its government.

To defuse the inherent colonial tension, President Obama and congressional Republicans offered a degree of deference. The seven board members —a bipartisan group of legal, financial, and policy experts, a majority of whom were Puerto Rican by birth— were to share some power with the local governor and legislature. The board itself decided not to hire a large staff, in part out of a desire, according to several sources, to avoid looking like it was setting up a parallel government. Rather, it would rely on consultants.

After PROMESA passed, Chappuis said he felt compelled to return home. He interviewed to be appointed to the oversight board but wasn’t nominated. So instead he suggested to his partners at McKinsey that the firm pursue Puerto Rico as a client. “I saw the work we’d started doing in the public sector,” he said. “I’m not going to mention specific names… but we did a lot of public-sector work around the world, even here in the Caribbean.” Following a competitive bidding process, McKinsey won the contract to serve as the strategic adviser to the board.

***

When McKinsey landed in Puerto Rico in November 2016, its first task, in Chappuis’s words, was to “unravel the hair ball of data, of systems, of issues” facing the island. The job quickly proved more challenging than he anticipated. He says the government didn’t have reliable figures on the number of people it employed, it had no unified payroll system, and it wasn’t even clear how much money Puerto Rico possessed. (Its creditors have accused it of hiding billions off its balance sheet.)

Chappuis assembled a team led by consultants with many years of experience in bankruptcy, public finance, education, health care, and many other technical subjects. They swarmed the capital, poring over the government’s finances; examining its agencies, schools, and prisons; and delving into the most granular aspects of governance. “People don’t come to work at McKinsey for the money,” Chappuis insisted, echoing a sentiment I often heard from the firm’s employees. Its entry-level salaries are generous, and its senior partners make millions, but that compensation pales in comparison to what Chappuis said he could make in, say, private equity or investment banking. “I have a team of people who are —I know the word passionate is used a lot— but we have people who are deeply, deeply committed to the work.”

To Puerto Ricans who came in contact with McKinsey consultants, however, it was a shock—like an emergency airlift from Harvard Business School. The firm recruits from the most prestigious universities and M.B.A. programs, with the majority of its young consultants staying only a few years before seeking their fortunes in the upper echelons of business and public life. Alumni include Sheryl Sandberg, Chelsea Clinton, and presidential hopeful Mayor Pete Buttigieg. In September, according to a filing in the bankruptcy case, the senior full-time consultant in Puerto Rico —acting as its “integrating thought leader”— was a 31-year-old graduate of Harvard and the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins. A recent graduate of Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government was doing “deep dives” into the education and tourism budgets as well as examining police-department pension projections. A 2016 graduate of Columbia University helmed the “right-sizing” initiative and assisted with financial calculations to, for example, identify a date when the government “would run out of funding were it to defer reductions” in personnel costs. The analyst handling hurricane-damage assessments was from Yale’s class of 2017.

Chappuis won’t offer much detail about the firm’s interactions with the government, but court filings, as well as oversight-board emails obtained via a lawsuit brought by the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo (CPI), reveal the dimensions of its intervention. McKinsey set what it refers to as an “aspirational vision” for the island. It advised the board on the proposed repeal of labor laws deemed too protective of workers. It tracked tax collections and projected health-care-cost inflation. According to invoices, it worked on “privatization options” for the highway authority and also the insolvent, patronage-riddled state-owned power company.

McKinsey stopped visiting in the immediate aftermath of the hurricane, but its consultants were back within weeks to survey the devastation, working on “power restoration” and “operational stabilization” at the power company. (It was crippled for months.) According to court documents, McKinsey sent consultants to San Juan’s airport to interview departing passengers to get “a sense for ‘what is happening on the ground.’ ” In what the consultants termed a “data poor environment,” they were trying to estimate how many people might leave the island for good in order to make accurate demographic and economic projections.

The power grid of Puerto Rico before and immediately Hurricane María. (September 24, 2017/Public Domain)

The oversight board’s demand for McKinsey’s services has only expanded over time. “It just keeps adding and adding,” Chappuis said, “and we keep absorbing.” But he said that despite the escalating work, McKinsey charges the board a flat fee that is below what private-sector clients pay.

Although PROMESA gave the oversight board the final say over the fiscal plan and budget, it left it to Puerto Rico’s government to identify specific cuts through what Chappuis describes as “a highly iterative process” involving numerous drafts and revisions of the plan. Still, with consultants taking on more and more responsibility, McKinsey has virtually become a shadow agency of the government, and a powerful one at that—feeding a colonialist dynamic that PROMESA was supposedly designed to avoid. In January, a federal official familiar with McKinsey’s work in Puerto Rico told me: “They’re doing everything. If McKinsey leaves, the board essentially ceases to operate.”

Chappuis disputes this characterization of McKinsey’s influence. “We, as the adviser, never make policy choices,” he said. “We’re fact finders, we’re analysts, and we’re framers of choices.”

Puerto Rico elected the 37-year-old Ricardo Rosselló governor soon after the passage of PROMESA. Although he campaigned on a pledge to put finances in order, his administration has been in constant, bitter conflict with the board and McKinsey. The first draft of the fiscal plan called for contracting the size of the government workforce by almost a third. That percentage has been reduced, but the initial target set the tone: The oversight board demands and Puerto Rico resists.

Under the plan’s current version, two-thirds of Puerto Rico’s 114 government agencies would be consolidated or eliminated, yielding an annual savings of $1.6 billion. The board would slash personnel costs, double the tuition at the University of Puerto Rico, and strip $153 million from the annual public-safety budget, partly by eliminating supposedly redundant divisions like the Rescue Squad. Since PROMESA was passed, Puerto Rico has closed or will close more than 450 public schools.

“It’s rare that a public institution forces itself to reform if they don’t have the driving reason to do so,” said the executive director of the oversight board, Natalie Jaresko, a former U.S. State Department official who oversaw a similar restructuring in Ukraine. (McKinsey was involved there, too.) Without McKinsey, she said, “it would be impossible to build a staff that is expert on every single issue.”

“Part of having to make choices,” she added, “is that it forces you to think.”

***

If Puerto Rico’s fiscal disaster has a ground zero, it is a brutalist concrete building in San Juan that once housed the Government Development Bank for Puerto Rico. During the run-up to the debt crisis, the bank —often referred to as the island’s “piggy bank”— issued a dizzying variety of bonds, securitizing Puerto Rico’s sales tax, gas tax, even taxes on rum, with underwriting assistance from Goldman Sachs and other investment banks. Each bond issue gave the government immediate cash while pledging revenues to investors for decades, thus mortgaging the island’s future. When I visited the bank’s offices recently, its seal was still on the wall, along with pictures of its past presidents. But it had recently been dissolved, leaving behind only the debt.

I was there to see Christian Sobrino, who greeted me wearing a casual GDB windbreaker. A young attorney, he was appointed by Governor Rosselló to wind down the bank. As the administration’s nonvoting representative on the oversight board, he serves as the governor’s voice. He was incensed with the board and McKinsey. “They have been trying to push layoffs—period,” he said. “We think it’s to punish a government that has not kneeled down and said, ‘Yes sir, whatever you want.’”

Christian Sobrino. (Photo via Twitter)

Soon after he started the job, Sobrino said, he met with Jaresko and, via speakerphone, McKinsey consultants. They presented him with a report, “The Path Forward”; on the first page, beneath the heading “The New Normal,” were three questions:

- What are you not going to do?

- What are you going to do differently?

- How does that decision lead to savings?

The patronizing tone, Sobrino said, was typical of McKinsey, as was what followed: charts projecting an imminent budget shortfall and outlining a “right-sizing initiative.” He expressed withering scorn for the “McKinsey-bots,” his name for what he described as a constantly changing cadre of hotshots who fly into Puerto Rico for short stints and treat local officials with condescension. “I think the first phrase I heard from a McKinsey-bot was, ‘We are going to corporatize the Puerto Rican government,’ ” Sobrino said. (No one at McKinsey could recall saying this, said a spokesman, adding that the statement “misrepresents both the goals and substance of our work.”) Sobrino contended that the firm has been supplying the oversight board with faulty analysis and fueling a perception that the island’s elected leaders were incompetent, a notion Trump has amplified. Last fall, I reached Sobrino by cell phone in Washington, where he said he was on a mission to counter a Trump tweetstorm inspired by the fiscal plan. “Not only are they not effective,” Sobrino said of McKinsey, “they’re causing harm to people.”

Complaints about the fiscal plan fall into several broad —and sometimes conflicting— categories. Critics such as Sobrino concede that some cuts were necessary but object to their being imposed clumsily by unelected outsiders. Others think the plan is not transformative enough. Dentist Rafael Torregrosa lobbied in vain to persuade McKinsey to consider health options that were less reliant on private insurers. “We’re paying good money to them as consultants of la junta to push only one model,” he said, “which happens to be the worst model in health care.”

The overwhelming sentiment, though, is sheer exhaustion with austerity. After Hurricane María, there was an expectation that the debt would be quickly resolved, with bondholders accepting a giant reduction in what they are owed — a “haircut,” in bankruptcy terminology. Hopes for debt forgiveness were bolstered by bankruptcy expert Donald Trump. “We’re going to have to wipe that out,” the president told Fox News two weeks after the hurricane. “You can say good-bye to that.” But administration officials quickly walked back his statement, and creditors are still fighting to be paid.

“We’re just being squeezed, squeezed, squeezed,” said Luis Carlos Robles, who works for a nonprofit that serves an impoverished San Juan neighborhood. His community of 26,000 people surrounding the Caño Martín Peña —a polluted, debris-choked waterway— had absorbed a double blow. María left around a thousand people there homeless, while the budget cuts led to the closure of four of its eight schools and the possible cancellation of a planned government dredging-and-redevelopment program. Crime is “exploding,” Robles said, with gangs committing murders in broad daylight and victims sometimes left lying in the street for hours.

Protesters in New York City during one of the control board meetings (Photo by Centro de Periodismo Investigativo)

Perhaps the most hotly contested part of the government-restructuring process is the issue of public safety. According to the fiscal plan, Puerto Rico spends almost $10,000 more per violent crime than the median state. “The conversation to date has been about ‘We don’t have enough money,’ ” Chappuis said. “It’s not the right way to frame it.” He said the police force has plenty of funding and has avoided layoffs by reducing its personnel costs through an early-retirement program and other attrition measures. But that was foolish, Chappuis argued, incentivizing the best and most experienced cops to leave. The fiscal plan’s solution was to have cheaper administrative staff do the office work, which would keep the police officers in the field.

The government and the police union maintain that austerity has ruined morale. Union leaders claim officers are working without disability or life insurance and their pensions are in jeopardy. The fiscal plan proposes reductions in overtime and “procurement optimization,” which translates into cheaper and less reliable guns, from the unions’ point of view. The changes have led to an exodus of some 1,700 officers in the last three years.

The police force has been consolidated with other emergency services into a unified Department of Public Safety, and that has led to competition for scarce resources. Bodies have piled up at the morgue and rape kits have gone untested at the Institute of Forensic Sciences. When the Firefighters Corps was shorthanded, the public-safety director, Héctor Pesquera, said he had to divert money from the police. “These budgets that the board imposed, I was not consulted at all,” he said. He complained that the oversight board’s red tape slowed his efforts to procure basic supplies, like bullets.

Héctor Pesquera (Photo by Centro de Periodismo Investigativo )

McKinsey has managed to find a few allies in local government. “The McKinsey fiscal-plan people are all over my numbers,” said Julia Keleher, Rosselló’s education secretary, in January, but she was happy about it. The school system has reading scores on a par with Jordan’s and Moldova’s, and Keleher, a fast-talking 44-year-old native of Philadelphia, said many of the schools that the plan targeted for closure had small enrollments. Shuttering them and shedding some 2,000 teachers would free up resources to strengthen the schools that remain, she argued. McKinsey separately helped her with a foundation she set up to support her work with the schools. “I’m trying to create that sense of being connected to a larger community of experts,” Keleher said. “It’s very difficult on an island.”

The school closings were extraordinarily unpopular. At the beginning of April, Keleher resigned under fire amid reports of an FBI investigation into her department. In an email, Keleher said the controversy surrounding her “explains a lot about why PR is in the condition it’s in,” and claimed that corruption in the department was something she had been trying to clean up. “What I’m living through is insane and destructive,” she wrote. Pesquera resigned as well shortly after he criticized budget cuts at a public hearing convened by the board. Nowhere has the hostility toward the fiscal plan been more intense, though, than at the University of Puerto Rico. “I’m an economist,” said professor Juan Lara. “I know that when you have a crisis like this, you do have to renegotiate the debt and have an austerity program. My complaint is that it’s not being done right.”

Julia Keleher’s official headshot

Lara questions both the depth of the cuts and where much of the projected savings are going: into the pockets of investors holding Puerto Rican bonds. “After the hurricane, it was basically taken as a given by everyone, including me, that there was going to be a very large haircut,” Lara said. But the federal judge overseeing the bankruptcy recently approved a settlement involving some $17 billion worth of bonds tied to Puerto Rico’s sales-tax revenues. The group of creditors with the strongest legal claim —many of them hedge funds— were set to get around 93 percent of their money back, less a haircut than a slight trim. (Meanwhile, a weaker group of creditors, who are mainly Puerto Rican, were likely to lose about half of their investment.) Even after the renegotiation, Lara predicted that the cost of servicing the debt would be so high that Puerto Rico would soon default again.

One afternoon, Lara took me for a walk around campus, where signs of decline and dissension were everywhere. GALLETAZO AL PLAN FISCAL, read a slogan spray-painted on a chipped concrete wall. With a loud crack, Lara slapped his hands together.

“Galletazo is like a slap in the face,” he translated.

The semester had just begun, and Lara had noticed a marked decrease in the number of students around campus, which he attributed to fewer scholarships and sharp tuition increases, as dictated by the oversight board. He is 68 years old and suspects he will never see his pension.

Outside a classroom building, Lara and I passed one of his students, Gabriel Negrón, a curly-haired 19-year-old student leader. He was in the middle of painting an American flag with a Spanish slogan decrying “thievery and piracy.” The next day, I saw him waving it at the rally outside the federal courthouse, where protesters chanted slogans attacking la junta and hedge funds. “The vultures,” Negrón said, “are just going to keep draining Puerto Rico.”

***

To Negrón, McKinsey was just another vulture. The Puerto Rican protesters didn’t distinguish between the hedge funds who owned the debt and the global consulting firm that was working out the bankruptcy. From their perspective, it was a predatory circle: Global financial institutions invented exotic new debt instruments; sophisticated investors bought them, even as they plunged into default; and then the high-priced consultants came along to ensure that Puerto Rico paid the bill. Their cynicism was reinforced by a very real controversy over allegations that McKinsey secretly reaped financial rewards from the oversight board’s decisions on the debt. The issue came to light after the prodding of a determined McKinsey antagonist named Jay Alix, who for years had been trying to expose what he considers the firm’s web of self-enriching conflicts of interest.

Alix is the retired founder of, and largest shareholder in, a corporate-bankruptcy consulting firm in direct competition with McKinsey. Typically, bankruptcy consultants and lawyers file sworn statements disclosing dozens if not hundreds of client relationships. Yet McKinsey’s were brief and opaque and hardly appeared to capture the vast scope of the global consulting firm’s client network. After a series of frustrating meetings with McKinsey executives, Alix decided to launch his own investigation. He formed a shell company and bought unsecured debt in several businesses for which McKinsey was acting as a bankruptcy consultant, and then he began agitating for more disclosure in court. When the firm complied, grudgingly, scores of potential conflicts of interest were discovered. Alix promptly filed a federal lawsuit claiming that McKinsey was a “criminal enterprise” engaging in bankruptcy fraud.

Alix’s probe soon ventured beyond the narrow realm of bankruptcy, peering into a rarely discussed part of the firm: the McKinsey Investment Office. Founded in the 1980s to manage partners’ retirement money, the MIO has some $12 billion in assets. It invests some of the money in outside hedge funds and manages some itself. A 2016 Financial Times report revealed the MIO’s in-house hedge fund had turned a profit in 24 of the past 25 years—and Alix didn’t think that the stellar track record was a coincidence.

“The MIO,” he said in a deposition, “is central to the business model of McKinsey & Company.”

McKinsey has long compared the MIO to a blind trust over which its consulting wing has no control. Yet last year, spurred by Alix, a Justice Department regulator investigated the MIO and concluded that it was not, in fact, operating as a blind trust: The partner who founded McKinsey’s subsidiary focused on bankruptcy also sat on the MIO’s board and served on the committee that oversaw investment decisions. McKinsey agreed to settle the DOJ’s case by paying $15 million without conceding fault.

One of the bankruptcies the MIO had an interest in was Puerto Rico’s. Last fall, the Times reported the MIO had a significant investment in Puerto Rican debt. The resulting outcry, in Congress and Puerto Rico, forced the oversight board to hire yet another consultant, a law firm, which released the February report concluding the MIO operated independently and that there was “no evidence” McKinsey’s consultants “knew about this direct investment, let alone altered their behavior because of it.” Moreover, the report said, McKinsey’s failure to disclose the investment wasn’t illegal, because PROMESA doesn’t require the same disclosures as bankruptcy law. “We just don’t think about MIO as part of our work,” Chappuis said. He told me his team had been taken by “complete surprise.”

“I wish people could actually shadow our team for a few days,” he continued. “I guarantee you their heads would blow up with the complexity and intensity of the task in Puerto Rico. I wish people could also see the from-to.” That pushmi-pullyu term was the consultant’s way of saying “progress.”

***

This past January, the major topic of conversation in Puerto Rico, splashed all over the newspapers, was the story of a rebellious, debt-ridden colony and one framer’s efforts to imbue it with fiscal discipline. I speak, of course, of the musical Hamilton, which had a monthlong run in San Juan, with Lin-Manuel Miranda reprising the title role. The production ran into political complications. A plan to stage the show at the University of Puerto Rico was abandoned at the last minute, after campus activists threatened to protest austerity. But a more welcoming venue was found, and on opening night an audience of theater-loving tourists, visiting dignitaries and farándula —the local glitterati— gave Miranda a thunderous standing ovation. In the second act, the audience swayed along to a showstopping number, “The Room Where It Happens,” about the backroom deal Hamilton worked out to pay off America’s creditors.

Proceeds from the musical were going to benefit hurricane-ravaged arts groups, but the event doubled as a celebration of the progress Chappuis wished the rest of America could see. As Miranda took his bows at the end of the show, he wrapped himself in a Puerto Rican flag. Afterward, he attended a rum-soaked party at a fancy office complex owned by one of the production’s sponsors, Banco Popular. Puerto Rico’s tourism sector is starting to revive. (The Times named the island its top destination for 2019.) New federal assistance, such as a program that designates the entire island as an “opportunity zone,” will offer a lucrative tax break for investments in small businesses, real estate, and the like. And Hurricane María, ironically enough, has generated an unexpected windfall. The current fiscal plan estimates Puerto Rico will receive $82 billion in disaster relief and predicts a substantial stimulus effect. Tax revenues increased by $540 million owing to recovery-related activity in 2018, the board estimates.

Puerto Rico’s Capitol building (Brad Clinesmith)

“The debate now is about the magnitude of the windfall,” said Brad Setser, an economist at the Council on Foreign Relations, who worked on PROMESA as a Treasury Department official. “And whether the windfall goes to creditors or Puerto Rico.”

This is the biggest unknown in McKinsey’s calculations, and it’s subject to highly unpredictable forces. First, Trump is vehemently opposed to giving Puerto Rico the $82 billion it anticipates, and if the figure is lower, the economic stimulus will be smaller. Second, whatever the size of the boost to tax revenue, how it’s allotted will be determined in court. The bankruptcy proceeding is a bloody battle involving many types of bonds and classes of creditors, each with varying legal claims. Some bondholders contend that Puerto Rico is simply trying to wriggle out of paying back the money it borrowed, and they want McKinsey and the board to get tough with the government. “Even though they are there to be the debt collectors, they’re doing a lousy job of it,” said Cate Long, a former financial journalist who now runs an analysis firm that works for some of the creditors.

Gradually, the oversight board and its expensive lawyers are hashing out deals with different groups of bondholders. Each settlement leaves a little less for McKinsey to work with in the fiscal plan. “What are we getting for the money?” Lara asked, referring to McKinsey’s consulting fees. “You get the colonial affront, you get the high cost, and you don’t get the product. That is probably the worst part.”

But Chappuis said things are beginning to change for the better: “The root system is taking hold. We just need to keep pushing through for the plant to start showing green shoots.” Whatever critics might say, he saw tangible improvement over the past two years in longtime problem areas such as fiscal management, education, and the power authority, which will soon be privatized. “We believe that addressing these foundational elements is the really tough work of transformation. Very few people have vocations for it in political administrations because they don’t have incentives to think in more than four-year stints.”

While some might consider the signs of a short-term economic revival a reason to dial down the austerity measures, Chappuis said the stimulus projections have only strengthened McKinsey’s case for transformation. “We’re going to have three or four good years. Let’s take advantage of them to right the ship.” Of course, that presumes that Trump is bluffing and the government aid is coming, that the courts will rule favorably, and that reality will bend to McKinsey’s rational analysis.

Polls might show that the fiscal plan is deeply unpopular, but Chappuis said he thought the board could still win over his fellow Puerto Ricans. “I’ve talked to the Uber drivers, the taxi drivers, the people. I hear everybody saying, ‘Of course we need someone to come in and fix this mess.’ ”

If a solution is ever found, if a deal is ever done, McKinsey is sure to be in the room where it happens.