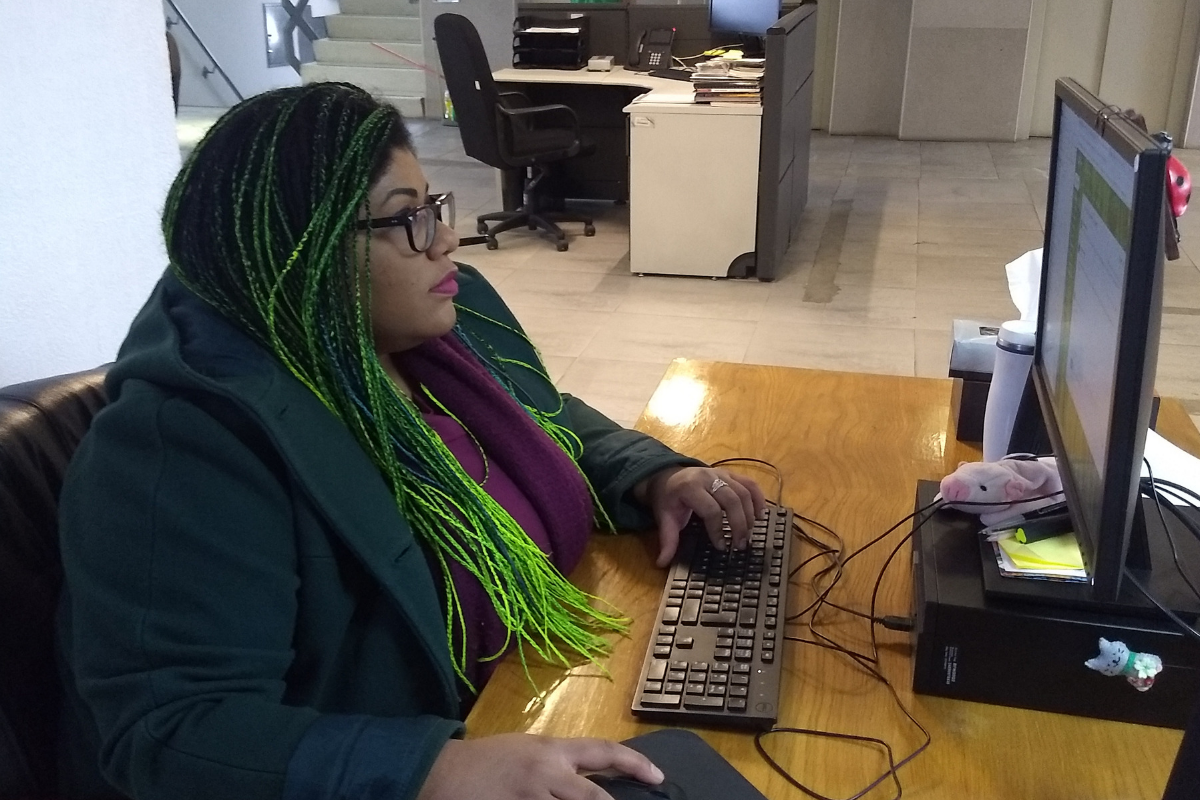

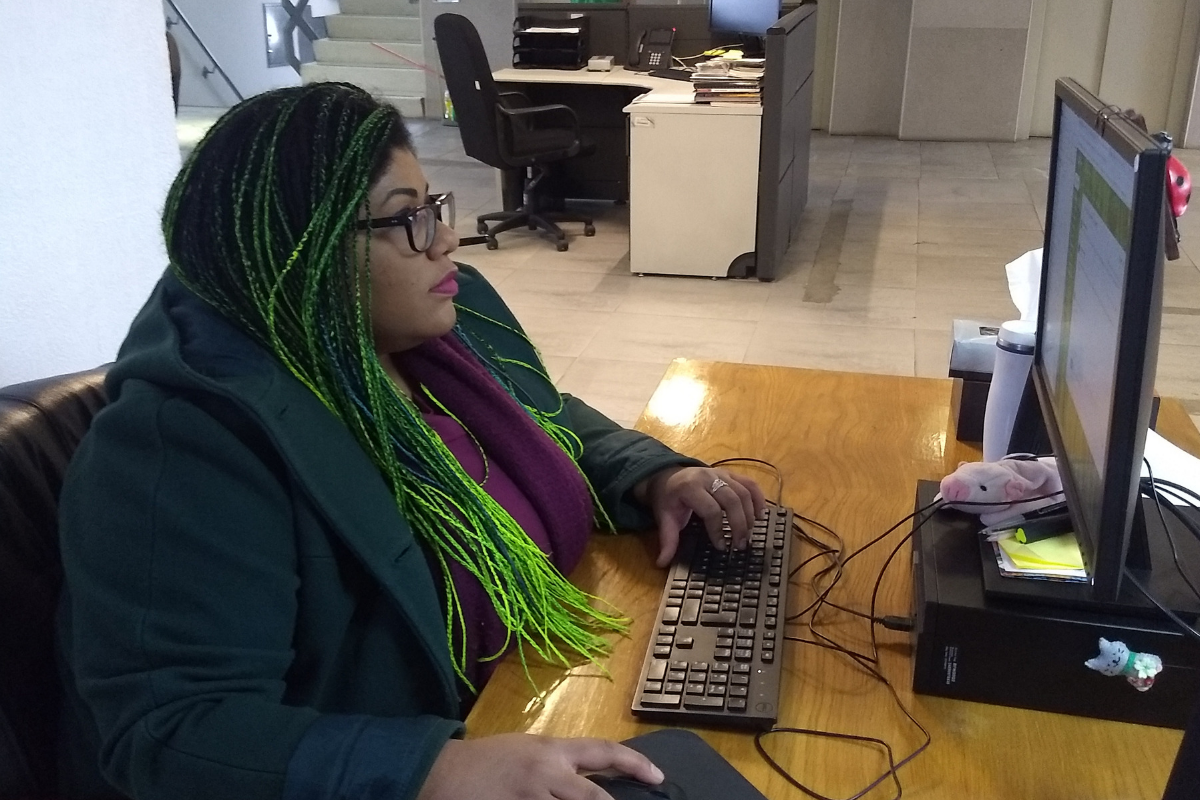

Georgina Diedhou. (Photo by Jonathan Custodio/Latino Rebels)

Georgina Diedhou had a rough time growing up.

Her father immigrated to Mexico from Senegal and met her mother in Mexico City, who was born and raised in Puebla. Diedhou has dual Mexican and Senegalese citizenship. Though she’s encountered many who reduced her negritude to her Senegalese background, the 29-year-old is quick to point out that her grandmother hails from Litzma de Tehautepec, a mostly Afro-Mexican town in the southern state of Oaxaca, which has the second-highest percentage of the afro-descendant demographic in the country.

At a time when local activists take to the streets to fight for the protection of women, she believes that her struggles are representative of what black women face in Mexican society—and has dedicated herself to educating the community in order to fight back.

Diedhou works with the National Council to Prevent Discrimination (CONAPRED) and has spent the last 7 years developing courses, workshops, and conferences to better educate the masses on topics of discrimination, including rights’ violations, racial profiling, racism, xenophobia, racial segregation, Anti-Semitism, homophobia, transphobia, lesbophobia, and other systems of oppression.

Facing Bullying and Anti-Blackness

“What most affected me was the bullying when I was a girl,” Diedhou told Latino USAabout her experiences growing up. Along with her three sisters, she went to a Franco-Mexican primary school on a scholarship. “It’s a school where there are only children of political officials and powerful people in the country. My parents only spent on materials, book bags, clothes, food and transportation,” she explained.

The bullying entailed a combination of racial and physical violence. “There, violence had to do with skin color: punches, putting your stuff in the trash, pushing you, threatening you. And all from a vision of ‘it’s because you’re black. You deserve it; you’re a slave.’ After years of violence as a girl, it affects you so much that you return that same violence to defend yourself,” she recalled.

She and her siblings ended up losing their scholarships due to Mexico’s economic crisis in the mid-1990s, which was tied to the Mexican government’s abrupt devaluation of the Mexican peso versus the U.S. dollar. Coupled with national political disarray, including the assassination of a 1994 presidential candidate, foreign investors shied away from the country as an asset.

Though her time at the school was done, the trauma had only just begun. At only 9 years old, Diedhou began to be hyper-sexualized and assaulted by teenage boys and older men.

“I had the body of a woman as a 9-year-old girl. Here in Mexico, there is a culture of assault and hyper-sexualization. Adults follow you and tell you obscenities in the street,” she said.

Sexual Abuse in Mexico

Data from Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) shows that 25 percent of women have suffered sexual abuse before turning 18-years-old and according to a Brain-Gallup poll, approximately 46 percent of Mexican women say they have been sexually assaulted.

Diedhou believes it’s worst for black women. “[Men say] ‘Oh, of course, she’s a fiery black woman , a black woman that deserves it, and a black woman that will facilitate services or sexual goals.’ From a misogynist or machismo vision, how many men carry themselves in Mexico, it’s like ‘I’ve never thrown around a black woman before—well, I deserve to live that experience.’ So, to have sex with a black woman is different because they exoticize you,” she said.

The culture of the hyper-sexualization and sexual harassment of women often expands to other forms of gender violence. According to Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), 43 percent of women over 15-years-old have suffered abuse from their partners, 53 percent have suffered violence at the hands of strangers, and 66 percent have confronted some form of sexual, physical, emotional, or economic violence.

For Diedhou, the treatment didn’t stop once she grew into adulthood.

“In high school and college, it was the same. From teachers who assault you to students who assault you in the street,” said Diedhou, who also notes that the objectification and abuse was accompanied by discrimination in the classroom. “At the university, it was ‘if you don’t take off what you have on your head, you’re not entering my class.’ [The professor was referring to] my red braids. That was my first confrontation with my psychology professor,” she said.

“Dreadlocks are dirty, a symbol of dirt and abandonment,” she remembers him saying.

When Diedhou began looking for a job to help pay for school, she continued to be subjected to discrimination based on her hair. She interviewed for a job to as a receptionist at a spa and recalls the employer telling her, “Yes, I’ll hire you but take that off your head. It’s kind of dirty. It’s a bad image for business.” She denied to do this, saying, “I’m sorry, but no. This is my natural hair. No.”

She didn’t get the job.

Rosa María Castro, director of the Women’s Association on the Coast of Oaxaca, an organization that holds both local and national forums and conferences geared towards equality for Mexican women, says it’s difficult for women to think about anything other than survival after a traumatic experience. “Their priority is to survive that violence. It’s not to study. It’s not to work. If proper attention is not received, women remain stuck and stop having aspirations,” Castro said.

Historically Ignored

At the moment, there is a movement of women in Mexico who have taken to the streets to fight against sexual assault and harassment after several policemen were accused of raping teenage girls on two separate instances.

Author Eren Cervantes-Altamirano noted on Twitter that often it is indigenous and Afro-Mexican women who are targeted by violence.

“One cannot forget that the women most commonly raped, disappeared, and killed are those living at the intersections of poverty, youth, Indigeneity, trans identities, queerness,” Cervantes-Altamirano tweeted, before noting the recent murder of Carmela Parra Santos, a local Afro-Mexican municipal leader.

When I wrote this during the weekend, I was thinking about how #Indigenous women are often the targets of state-sanctioned feminicide. Today #CarmelaParra was murdered, an Afro-Indigenous leader fighting for Indigenous land and autonomy. #NoMeCuidanMeViolan #NiunaMas https://t.co/24CrOj608g

— Eren Cervantes-Altamirano (@ErenArruna) August 20, 2019

Though Dieghou acknowledges that there are many others who can speak to the topic, Diedhou feels that the Afro-Mexican community has been historically ignored and that change does not happen without obstinate persistence—a belief that drives her work.

“There are many people who are Afro and they don’t know it. They think that they’re brown or black because the sun hit them or because that’s how they were born; that it’s something in the genetics but nothing more,” said Diedhou, who is firm in her own identity. “I’m black before whatever else,” she affirmed.

***

Jonathan Custodio is a freelance journalist based out of The Bronx. He has reported on race and identity in México for the Pulitzer Center and has covered hyperlocal issues in the Northwest section of The Bronx for the Norwood News. He is currently finishing his B.A. in Journalism at Lehman College.