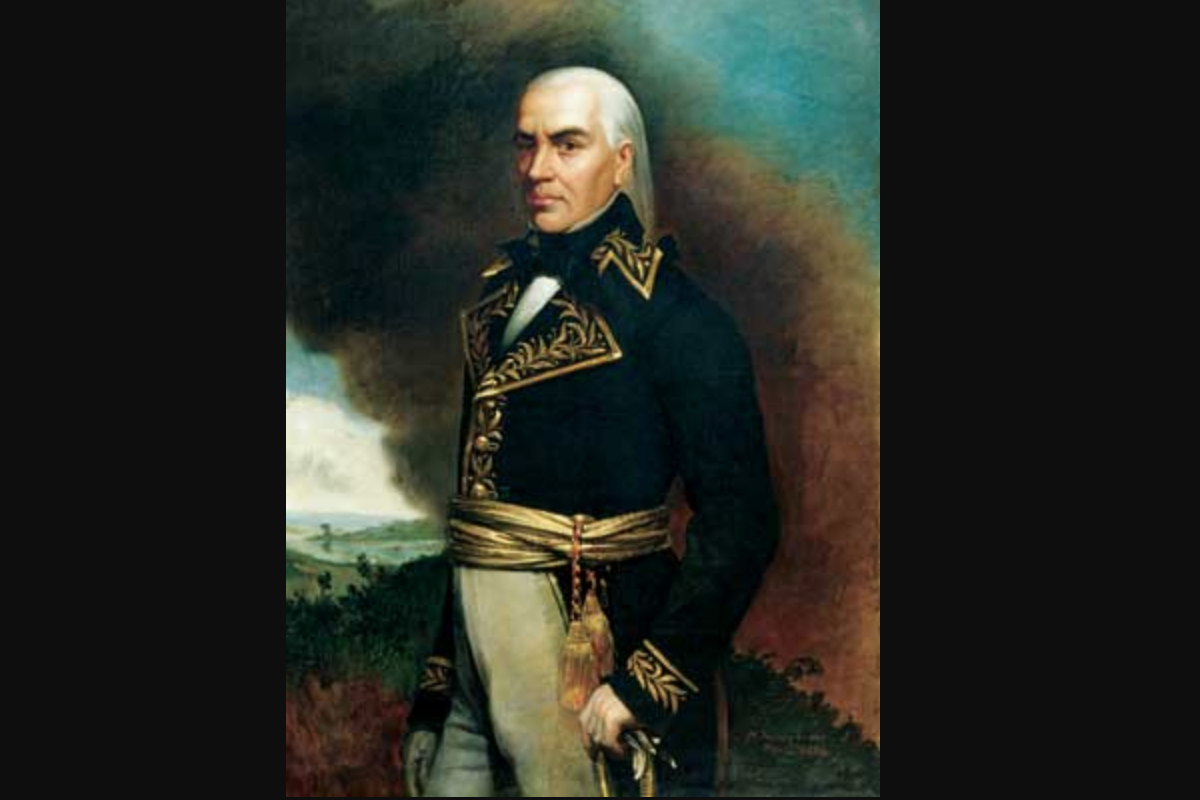

Portrait of General Francisco de Miranda by Martin Tovar y Tovar (Public Domain)

In 1805, Venezuelan revolutionary Francisco de Miranda arrived in Washington D.C., the new capital of a new nation. He demanded an audience with high-ranking members of the United States government to discuss his lifelong ambition: The independence of the Spanish colonies and, more specifically, if the U.S. would help Spain, one of their allies during the American Revolution, or if they would, in Miranda’s own words, “wink at it.”

It was Miranda’s second time in the United States, having visited Philadelphia in 1783 when he was a 33-year old Spanish officer from Caracas and veteran of the Siege of Pensacola. Persecuted by the Inquisition for his liberal views, Miranda defected from the Spanish army and traveled from Stockholm to Kiev to Istanbul, fighting in the French Revolution where he rose to the rank of general.

After barely avoiding the guillotine, Miranda settled in London and focused on his revolutionary project: A united Spanish-speaking nation in the Americas, spanning from California to Tierra del Fuego, with the strength, population and resources capable to rival the nascent United States in the north or the powerful and always-hungry European empires.

He approached British Prime Minister William Pitt with a proposition to invade Venezuela. Ultimately, Miranda grew worried that they would override the revolution make the country a colony, expanding their nearby possessions in Trinidad and Guiana.

Author, historian and member of the Venezuelan Academy of History Edgardo Mondolfi Gudat told Latino Rebels about Miranda’s motivations: “Another factor that carries weight is opportunity. Miranda, who had trusted so much in Great Britain to support or approve his proposals, [sees the British government] at the time had overcome its tensions with Spain so he has no other option than try his luck over the United States.”

Miranda met with U.S. President Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of State James Madison. In his writings at the time, Miranda expressed high spirits for what he understood as covert support but expressed ambivalence to what he actually witnessed.

“They have their eyes set on Mexico,” he wrote after a meeting with Madison.

About his meeting with Jefferson, Miranda wrote: “He showed us a two-headed snake and other curio that proclaim frivolity and a spirit more proper to the Literary than the government of a great State.”

Patrick Iber, a U.S. historian and Assistant Professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, shared his thoughts with Latino Rebels about this era. For him, “[the United States] was never ‘isolationist’ in the sense of not seeking to influence events outside of its borders or not participating in the international system.”

According to Iber, two priorities of the federal government at the time were to keep a distance from the more powerful European powers and protect their commercial interests. This led to “the development of the idea of a separate Western Hemisphere free from European incursion,” Iber explained.

The historian added that by 1811 the U.S. Congress had made a declaration welcoming the independence of Spanish American colonies and “though France and Spain were indeed allies during the [American] revolution, that changed quickly.”

Some of Miranda’s friends in the U.S. government were Alexander Hamilton and Henry Knox, but with the former dead and the latter retired, his most influential supporter was Colonel William Stephens Smith, a New York customs official and brother-in-law of John Quincy Adams. Years later, Miranda wrote the following about Adams:

“His constant topic was the independence of South America, her immense wealth, inexhaustible resources, innumerable population, impatience under the Spanish yoke, and disposition to throw off the dominion of Spain. It is most certain that he filled the heads of many of the young officers with brilliant visions of wealth, free trade, republican government… in South America.”

The Failed Invasion

Smith introduced Miranda to merchant Samuel Ogden, who procured weapons, supplies, men and an 18-cannon ship named the Leander. On February 2 1806, the Leander left New York on its way to the Caribbean.

The majority of the crew of 120 were Americans and, although a few believed in Miranda’s cause, such as such as William Steuben Smith —Colonel Smith’s son— others, as Mondolfi Gudat points out, were deceived into join: “[It was an expedition] marked by secrecy, marked by some mystery on [its] goals. Some of the recruits, not all, didn’t have all that clear their destination.”

One of them, a New Jersey native called John Edsall, described his situation in the following terms: “I was villainously sold to assist furthering the views of a set of aspiring men in overturning the laws and government of a country which they had nothing to do, and whose inhabitants cursed them for the pretended protestations of liberation from laws better than they themselves were capable of framing.”

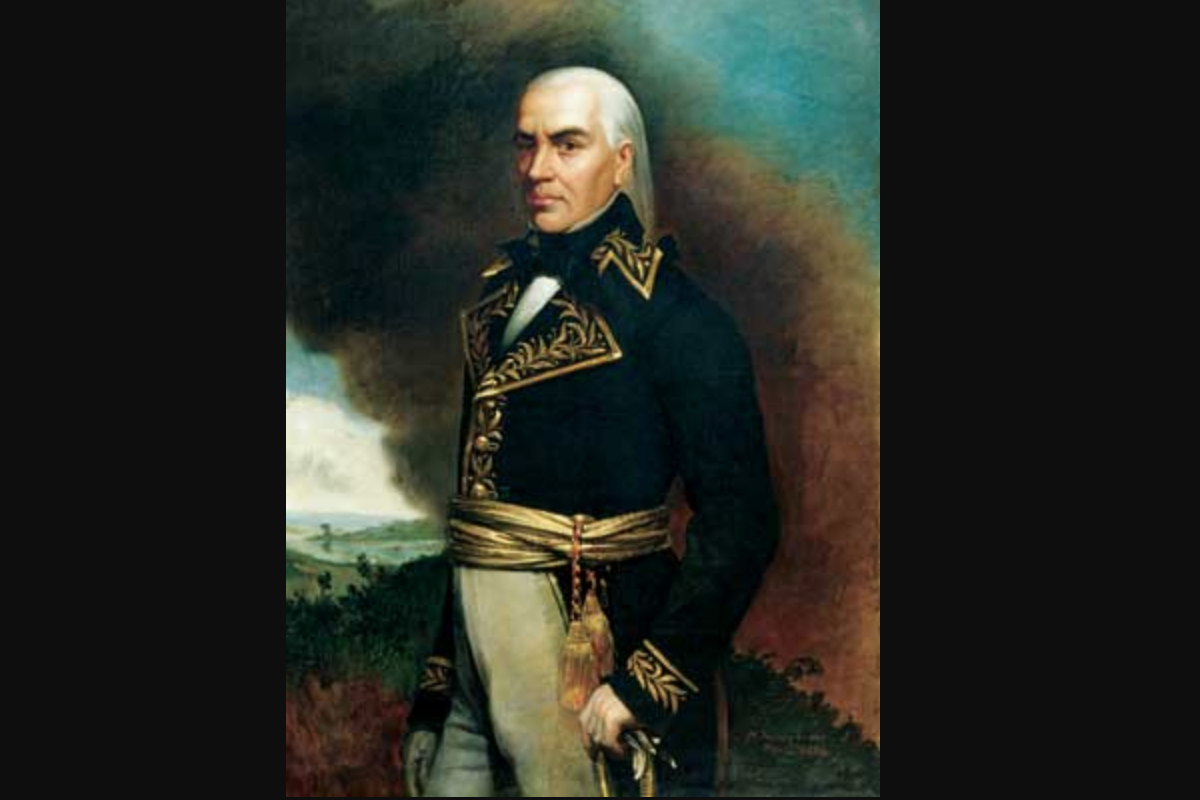

Forced to remain in Jacmel, Haiti, for several weeks under the protection of General Alexandre Pétion, Miranda’s expedition acquired two other ships. On March 12, Miranda hoisted a horizontal yellow, blue and red flag. His design would later would serve as inspiration for the current-day flags of Colombia, Venezuela and Ecuador.

Flag that Miranda used in 1806 (Public Domain)

Later that year in April, a disastrous first landing near Puerto Cabello ended with the Spanish navy seizing the ships acquired in Haiti and Miranda fleeing to Trinidad. Sixty crew members were imprisoned, including Steuben Smith and Edsall. Ten of them were executed for piracy.

Colonel Smith and Ogden were arrested for violating neutrality towards Spain. They maintained to have acted following orders by Jefferson and Madison, causing a scandal. The duo was quietly acquitted and the whole affair died out.

In early August of 1806, Miranda assaulted La Vela de Coro near Curaçao, taking the local garrison, hoisting his flag on the Ayuntamiento, and proclaiming independence. Nonetheless, failing to gather local support, Miranda set sail to Aruba and eventually returned to England.

For Mondolfi Gudat, the curiosity of Miranda and a group of American recruits, far from the capital, demanding loyalty helps to explain the lukewarm response: “You have to understand the weight of mentality and traditions and deeply-rooted prejudices. It’s not enough to decree freedom to make it happen.… The response of the locals was one of fear and caution to this adventure.”

Five years later, on July 5 1811, Venezuela declared independence from Spain, establishing a federal republic modeled after the United States. Miranda was among the signers, after Simón Bolívar and other patriots personally went to London to request him to return to Caracas and take command of the military.

The new republic roughly lasted a year, falling apart among internal social upheaval, an invasion, and a devastating earthquake. Miranda, by then de facto leader of the republic, was handed to the Spanish authorities. He died in jail in Cádiz, southern Spain, on July 14 1816, never managing to see what all his attempts inspired.

***

José González Vargas is a Venezuelan journalist who has written for several outlets, including Latino USA, Latino Rebels, Caracas Chronicles and Into. He tweets from @Maxmordon.