Fire consumes an area in Altamira, Brazil, Tuesday, Aug. 27, 2019. Brazil insisted on Tuesday that it would set conditions for accepting any aid from the world’s richest nations to help fight Amazon fires, saying France couldn’t protect the Notre Dame Cathedral from fire devastation and should focus on its own problems. (AP Photo/Leo Correa)

By LUIS ANDRÉS HENAO and CHRISTOPHER TORCHIA, Associated Press

PORTO VELHO, Brazil (AP) — Acrimony between Brazil and European countries seeking to help fight Amazon fires deepened on Tuesday, jeopardizing hopes of global unity over how to protect a region seen as vital to the health of the planet.

A personal spat between the leaders of Brazil and France seemed to dominate the dispute, but it also centered on Brazilian perceptions of alleged interference by Europe on matters of sovereignty, economic development and the rights of indigenous people. Brazil said it will set conditions for accepting any aid from the Group of Seven nations, which offered tens of millions of dollars for firefighting and rainforest protections.

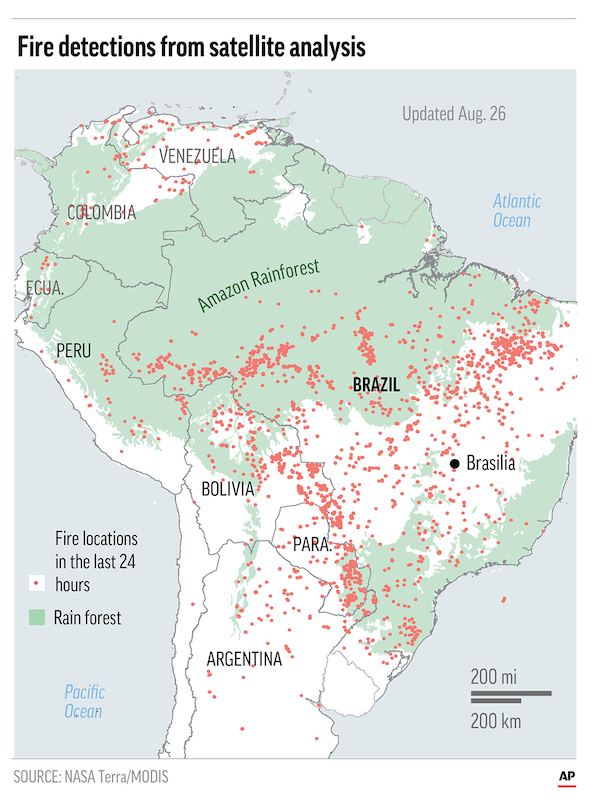

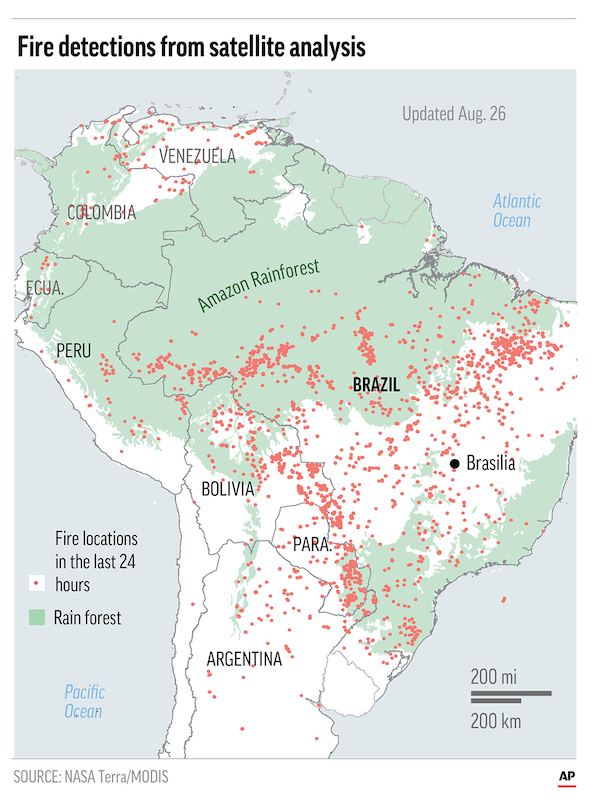

The Amazon’s rainforests are a major absorber of carbon dioxide, considered a critical defense against rising temperatures and other disruptions caused by climate change. While many of the recorded fires this year were set in already deforested areas by people clearing land for cultivation or pasture, Brazilian government figures indicate that they are much more widespread this year, suggesting the threat to the vast ecosystem is intensifying.

The effect of the fires was evident in the Amazonian city of Porto Velho, where a thick pall of smoke covered the sky for most of the day. Elane Diaz, a nurse in the city, spoke about respiratory problems while waiting for a doctor’s appointment at a hospital with her 5-year-old-son Eduardo.

“The kids are affected the most. They’re coughing a lot,” Diaz said. “They have problems breathing. I’m concerned because it affects their health.”

Still, Diaz and some other residents in Porto Velho, the capital of Rondonia state, were supportive of Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, saying he was doing what he could to protect the Amazon and that international criticism was unfounded.

“Germany had already been helping through NGOs and they couldn’t prevent this,” said Mona Lisa Pereira, an agronomist. “It seems like this is the fire of a lifetime. But it’s not. We have fires every year.”

Bolsonaro, who took office this year with a promise to boost development in Latin America’s biggest economy, has questioned whether offers of international aid mask a plot to exploit the Amazon’s resources and weaken Brazilian growth. On Tuesday, he said French President Emmanuel Macron had called him a liar and that he would have to apologize before Brazil considers accepting rainforest aid.

Macron has to retract those comments “and then we can speak,” Bolsonaro said.

In a video message, Brazilian novelist Paulo Coelho offered an apology to France for what he called Bolsonaro’s “hysteria,” saying the Brazilian government had resorted to insults to dodge responsibility for the Amazon fires.

Bolsonaro met governors of states in the Amazon region, some of whom criticized laws that protect the environment and the rights of indigenous people that they said limited opportunities for economic development.

Marcos Jose Rocha dos Santos, the governor of Rondonia state, questioned the intentions of international aid.

“International resources are welcome as long as who uses those resources is us,” Rocha dos Santos said. “We will determine where the money will be applied, it’s useless if those resources get here and go to international NGOs.”

At a summit in France on Monday, the G-7 nations pledged $20 million to help fight the flames in the Amazon and protect the rainforest, in addition to a separate $12 million from Britain and $11 million from Canada.

Onyx Lorenzoni, the Brazilian president’s chief of staff, sharpened the criticism, saying Europe should use the funds for its own problems.

“Macron could not avoid an obvious fire in a church that is a world heritage site,” Lorenzoni told the G1 news website, referring to the Notre Dame Cathedral that was ravaged by fire in April.

Macron, who has questioned Bolsonaro’s trustworthiness and commitment to protecting biodiversity, shrugged off the snub from the Brazilian president. The French leader said Bolsonaro’s interpretation was a “mistake” and that the aid offer is “a sign of friendship.”

He said the aid money isn’t just aimed at Brazil, but at nine countries in the vast Amazon region that also spans Bolivia, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Guyana, Suriname and French Guiana, an overseas region of France. About 60% of the Amazon region is in Brazil.

Even so, Macron has threatened to block a European Union trade deal with several South American states, including Brazil. He has also acknowledged that Europe, by importing soya from Brazil, shares some blame for agricultural pressure on the rainforest. Bolsonaro has previously said he wants to convert land for more cattle pastures and soybean farms.

In contrast to the tension between France and Brazil, U.S. President Donald Trump praised the Brazilian president. “He is working very hard on the Amazon fires and in all respects doing a great job for the people of Brazil – Not easy,” Trump tweeted Tuesday.

Bolsonaro also said that Japan is “extremely aligned with us” and seeks a deeper trade partnership with South American nations.

Brazil’s National Space Research Institute, which monitors deforestation, said the number of fires has risen by 85% to more than 77,000 in the last year, a record since the institute began keeping track in 2013. About half of the fires were in the Amazon region, with most just in the past month.

Neighboring Bolivia is battling its own vast blazes. The largest are in the Chiquitanía region, a zone of dry forest, farmland and open prairies that has seen an expansion of farming and ranching. President Evo Morales, who has been under criticism for an allegedly slow response to the fires, was in the region on Tuesday overseeing firefighting efforts involving more than 3,500 people, including soldiers, police and volunteers.

A volunteer heads to put out a fire at the Chiquitania Forest fir of Chochis near Robore, Bolivia, Monday, Aug. 26, 2019.

The Amazon has experienced an increased rate of fires during drought periods in the last 20 years, but the phenomenon this year is “unusual” because drought has not yet hit, said Laura Schneider of Rutgers University-New Brunswick.

Schneider, an associate professor in the geography department, said fire is commonly used by people to clear land for cultivation, and the actual area burned this year must be measured for an accurate comparison with damage in past years.

The funds offered this week by the world’s richest countries are widely viewed as useful but insufficient for dealing with the threats to the Amazon in the long term. Under international pressure, Bolsonaro has said he would make 44,000 troops available to fight the blazes.

However, federal prosecutors in the Amazon state of Para said they had warned Brazil’s environmental protection agency about a “fire day” organized by farmers earlier this month to clear land. The agency said it lacked support from military police to protect its field teams in risky monitoring operations, according to prosecutors.

Grace Quale, a laboratory technician at the 9 of July hospital in Porto Velho, said more people were undergoing tests because of respiratory problems caused by smoke. Children and the elderly are suffering the most, said Quale, who supports Bolsonaro and believes fires are being set by opponents trying to discredit him.

“What’s happening is disrespectful to our humans, to our animals, because if they end the Amazon, how will we survive?” she said.

***

Torchia reported from Rio de Janeiro. Associated Press writers Anna Jean Kaiser in Rio de Janeiro and Carlos Valdez in La Paz, Bolivia, contributed to this report.