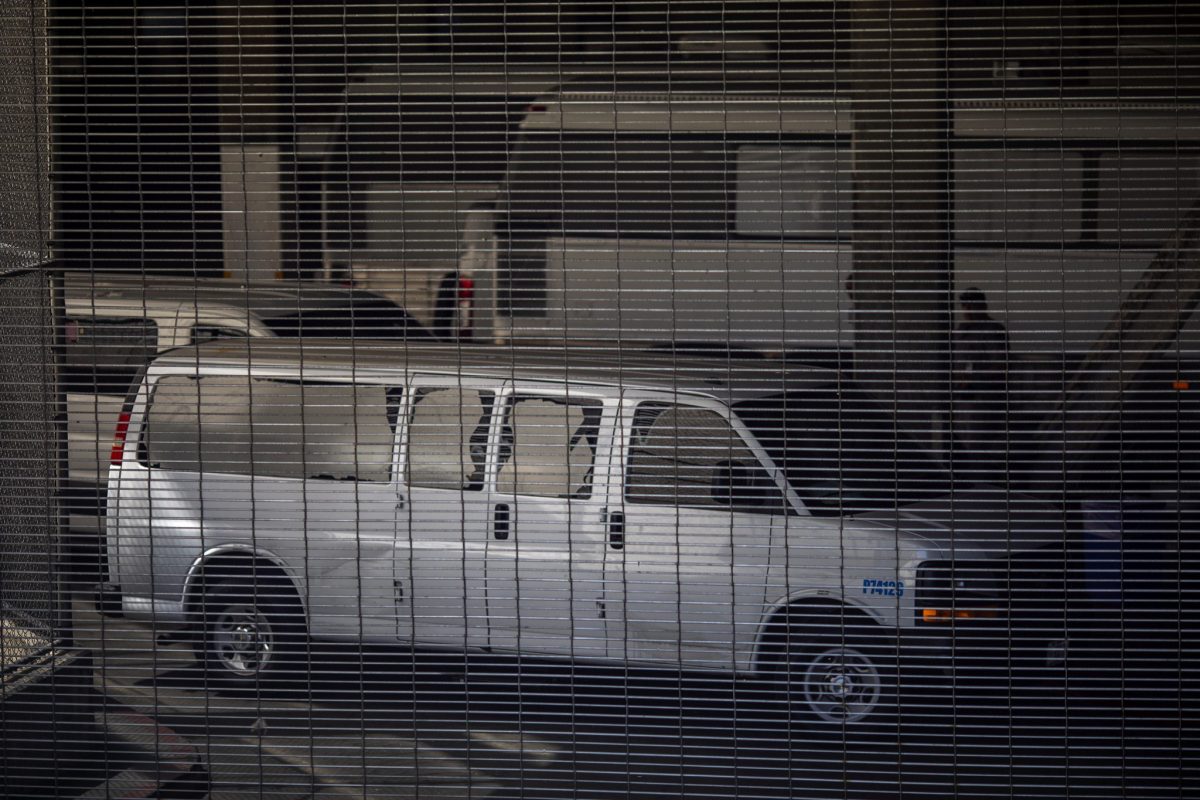

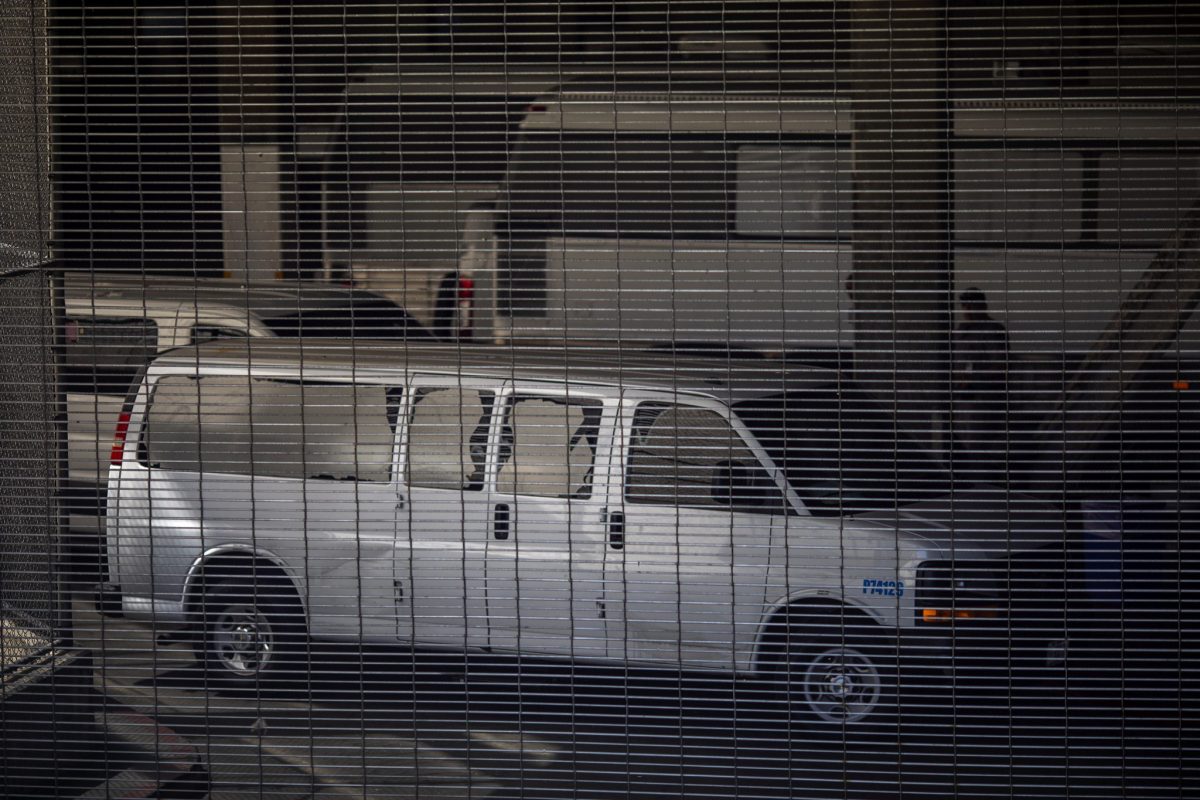

Vehicles are seen in an intake area under the Metropolitan Detention Center prison as mass arrests by federal immigration authorities, as ordered by the Trump administration, were supposed to begin in major cities across the nation on July 14, 2019 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by David McNew/Getty Images)

By Nourelhoda Eidy, Ronnie Alvarez, and Madeline Simone

As three students who spent our summers learning about the health impacts of immigration work raids, we find it is necessary to reflect on the implications of Trump’s interior enforcement tactics. Our research is enabled by accounts of people either directly affected by raids or those who helped with responding to the crisis. We recognize that immigration raids are largely politicized, which is evidenced by the increased number of large-scale worksite raids since Trump was elected in 2016. As a research group in the public health sector, we aim to draw connections between the human rights violations that are raids to the health and social implications they have on mixed-status communities.

To begin, two types of raids are either worksite or in the comfort of your own home. ICE enforcement can take many forms—as they frequently collaborate with local police, sometimes including SWAT-like units with no-knock warrants. One tactic is that local police will station checkpoints in neighborhoods with high concentrations of Latinx individuals and pull over cars. This tactic is highly driven by racial motives.

ICE often swarms facilities and/or homes in a hyper militarized fashion (with weaponry, and body armor), blockading all exits. In many cases, ICE has warrants for suspected drug activity or for employer arrests for exploitation of immigrant workers. These warrants serve as decoys because once inside the facility or home, ICE proceeds to racially profile all peoples perceived to be undocumented and arrests them. This is often referred to as “collateral arrests.”

Raids in worksites may result in hundreds of detainees. Once someone is detained, they are taken to a detention facility where they may not know the location. Due to being in an unknown location or location away from a major city, the process of obtaining legal representation takes even longer. Detainees are predominantly men who typically serve as the main breadwinner for their families. Consequently, families take a financial hit. Not only is the main source of income gone, but now there are increased expenses with legal proceedings.

If the court allows a bond for a detainee, they are difficult to pay due to financial limitations. The legal process involving immigration cases is a lengthy endeavor due to a backed up system and the extensive wait for court dates. Because of this, detainees may opt for voluntary departure, in which they choose to be deported to their country of origin to avoid such an extensive and expensive legal process. In many accounts, voluntary departure of an undocumented parent leads their citizen children to also leave for the purpose of family unification. This moves us into a conversation on how immigration enforcement affects whole families and communities.

As we’ve seen in our research, the spillover effect of these raids on a community is tremendous. An individual does not have to be directly involved in an immigration raid to suffer the health consequences. Affected communities are not limited to undocumented individuals, but also include those who are citizens in mixed-status families, permanent residents, or DACAmented. Members of mixed-status families, for example, live with pending sense of dread knowing that a loved-one, or many, have been raided, detained, physically abused, or deported as a result of these events.

There is a common theme of people living in a state of constant fear moving forward. It is a constant fear of what will happen to detained loved ones, a fear of anyone else from their family or community being removed, and a fear of ICE coming back.

Individuals respond to immigration enforcement with lack of trust in police and other social institutions. Something as simple as walking a child to school or sitting in a public park is avoided for fear of any encounters with officials. Additionally, fewer students attend schools in the days following a raid, creating an educational disadvantage for these students. Likewise, a combination of individuals not seeking out health services and the stress endured from the aftermath of such an event, leads to poorer health.

This can be evidenced by a study in 2008 after a worksite raid in Postville, Iowa, which concluded that Latina mothers experienced an increase in rates of low birth weight (LBW) in comparison to white women after the raid, regardless of their citizenship status. These health consequences can be condensed, lifelong, and even cross-generational. Whether they’re caused by the continuous fear of being detained, having limited access to healthcare, or plunging trust in government authority, these all contribute to an overall health crisis in immigrant communities.

Change is possible, and here is what we can do:

As a country, we need to take steps and create interventions that target various levels. As some politicians and groups continue to advocate for the goal of abolishing ICE, more immediate action is necessary and possible. On a national level, it is clear there must be stronger accountability procedures and transparency in ICE actions. This includes transparency in the treatment of detainees and the quality of facilities. ICE actions should be explicit in their warrant, and collateral arrests should be forbidden.

On both a structural and social level, we need to move away from reinforcing and attributing terms with negative connotations to this community. When detainees are held by ICE, they receive what serves as a case number but is referred to as an “Alien Registration Number.” The supposed leader of our country even refers to the drivers of our agricultural success as “illegal aliens.” These terms erase the reality that undocumented immigrants have shaped this country for decades. Further, when we eliminate the usage of these words, we decriminalize immigration, and stop treating undocumented individuals as felons. We need to stop treating undocumented individuals as any different from the people who founded this country, or the waves of Irish and German immigrants, who came to the United States to escape economic turmoil. The original immigrants who came to America came in pursuit of opportunity, this community is no different.

Our research has focused mainly on community level intervention and response. In the aftermath of the raids, we have studied, community organizations, including Iowa Welcomes Its Immigrant Neighbors (IowaWINs), have played an imperative role in working with different sectors, including legal services, teachers, religious leaders and Latinx/immigrant advocates, to provide a wide range of services. Organizations operate out of churches and create a system to bring families in and offer legal aid, therapists, day care, support for bond payments, etc. Additionally, they host educational workshops to spread knowledge of undocumented individuals’ rights, make families aware of how to respond when ICE appears at your door, and create preparation response methods should another raid occur. Therefore, many organizations, such as IowaWINs and O’Neill Cares Coalition, set up food pantries in churches and reached out to neighboring religious institutions to provide monetary or material donations. Most importantly, they bring a community that has been inflicted with so much pain and is living in fear together to foster an environment of social resilience and support.

These are a few of the many ways that the country can work towards reducing health consequences related to unfair and unjust immigration enforcement practices. We need to build better relationships and give gratitude to a community that has contributed so much to this country’s progress, rather than continuing to create a mythical enemy out of them. As three future health professionals and scholars, we reject the elitist definition of the American identity, and are ready to recreate a system of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness… FOR ALL.

***

Nourelhoda Eidy is a senior studying Community and Global Public Health.

Ronnie Alvarez is a junior studying Public Health Sciences with a minor in Chemistry.

Madeline Simone is a senior studying Biology, Health, and Society with a minor in Spanish.

They participated in research related to the “Health Impacts of Immigration Enforcement” research project, led by Drs. William Lopez and Nicole Novak, which draws on the work of Dr. Lopez’ book, Separated: Family and Community in the Aftermath of an Immigration Raid.