Trump says Argentina is intentionally weakening the peso. (FJZEA/Shutterstock.com)

By Farok J. Contractor, Rutgers University

President Donald Trump slapped new tariffs on Brazil and Argentina after accusing them of manipulating their currencies to boost exports.

It wasn’t the first time Trump has labeled another country a “currency manipulator” for supposedly meddling to keep its own currency weak or undervalued. China received that epithet from the president long before it felt the pain of his trade war.

But the truth is more complicated than Trump makes it out to be.

Everyone Does It

The first thing to understand is that government efforts to influence their exchange rates —which is often dubbed currency manipulation— is extremely common, as I’ve seen firsthand in my work as an international business professor.

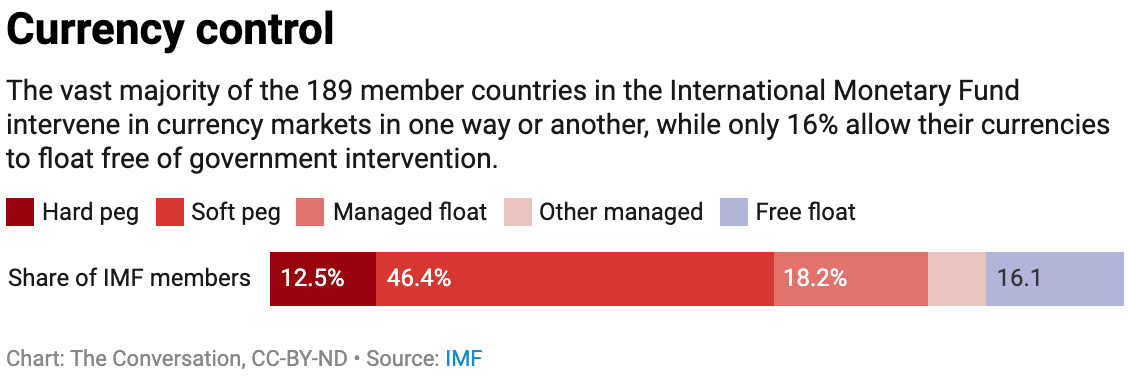

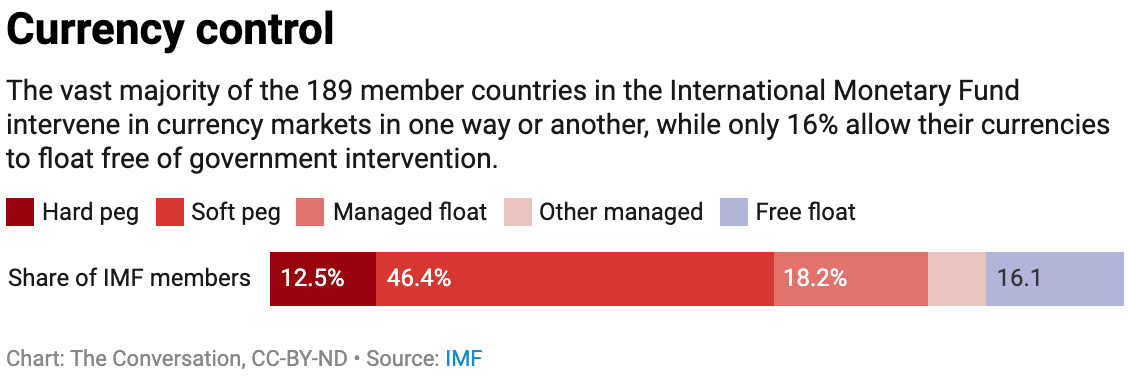

All but 31 of the International Monetary Fund’s 189 members meddle, in a mild or total fashion, to influence or fix their exchange rates. Only a few major currencies, such as the dollar or euro, are allowed a “free float” based on market forces of supply and demand with minimal or no government intervention.

Other governments have a variety of ways to manage their currencies. Some peg their currencies to a fixed rate, as long as they can afford to keep it there. Others tie their currencies to a major but stable currency like the euro or a basket of different ones. For example, the Lebanese pound is tied to the dollar at a fixed rate of 1,507.5 to 1.

About 16% of IMF members use a “managed float,” in which they allow market forces to play a role but with the government buying or selling their own currency as needed to bias the exchange rate upward or downward. Argentina and Brazil both adhere to a managed float system.

Why Weaken a Currency

Generally, when the Trump administration has criticized countries, the allegation is that their government is keeping its currency undervalued in order to give an artificial boost to exports while making it harder for imports to compete.

A weaker currency makes the products it sells abroad cheaper, while making imports more expensive for its consumers. This may have the effect of boosting jobs in that country. Trump believes this is what Brazil and Argentina are doing.

Brazil President Jair Bolsonaro in October, 2019 (AP Photo/Eraldo Peres, File)

Economists say the two countries are actually trying to prevent their currencies from weakening against the dollar. That’s in part because a weak currency also makes imports more expensive for businesses that rely on foreign inputs to make their products.

So higher import costs, along with persistently high inflation in both Argentina and Brazil, largely offset any gains from their weaker currencies.

The Strong Dollar

But more importantly, these currencies seem undervalued primarily because the U.S. dollar is unnaturally strong.

One reason for the strength of the dollar is that inflation-adjusted interest rates in the U.S. are still relatively high. Another is that the dollar is still a haven, making it an attractive place to park your cash during global economic uncertainty.

As a result, a massive amount of foreign money has flowed into dollar denominated-bank deposits, treasury bonds, U.S. stocks and real estate over the past few years. And the reality is that the dollar is now exceptionally strong, not that other currencies are weak or necessarily being manipulated.

Ultimately, labeling other countries as currency manipulators is more about politics and geopolitical relations than policy.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on July 13, 2016.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.