In this December 16, 2019 photo, Venezuela’s National Assembly President and self-proclaimed interim president Juan Guaidó speaks during a interview with the Associated Press in Caracas, Venezuela. (AP Photo/Matías Delacroix, File)

By SCOTT SMITH, Associated Press

CARACAS, Venezuela (AP) — Tour operator Alejandro Palacios joined hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans protesting in the streets early this year, wanting to believe that things would finally change in the country as upstart opposition leader Juan Guaidó rallied international support and promised a swift end to President Nicolás Maduro’s rule.

To Palacios, Guaidó seemed different from the string of past opposition leaders who had challenged Maduro and his predecessor, the late Hugo Chávez, over 20 years of increasingly authoritarian socialist rule.

The United States and dozens of nations had thrown their support behind the youthful congressional leader, recognizing him as the country’s legitimate president, arguing that Maduro’s re-election was invalidated by fraud and a ban on most opponents.

And there seemed to be signs that the military might heed Guaidó’s repeated calls for soldiers to abandon Maduro. A few joined him in the streets in a quickly quelled uprising. The U.S. and other nations sent caravans of aid to Venezuela’s borders to be distributed by Guaidó’s backers, and they were put in charge of many Venezuelan embassies and assets abroad.

Then February turned to March, and the months marched by. No international aid made it through Maduro’s blockade. The military stayed loyal. Even the nation’s catastrophic economy began to improve slightly. Maduro remains in power.

“Here we are today, like nothing ever happened,” said a disillusioned Palacios, 26, who has watched many relatives pack up and leave in desperation while he stayed behind to care for his parents living on a government pension constantly shrinking under the world’s highest inflation.

In this February 2, 2019 file photo, anti-government protesters take part in a nationwide demonstration demanding the resignation of President Nicolás Maduro, in Caracas, Venezuela. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd, File)

Palacios no longer answers the opposition leader’s call to protest, nor do most of the others who once filled the streets.

Cracks have even appeared in Guaidó’s base of support in the National Assembly, the only major institution controlled by the opposition. His re-election as congressional president is no longer assured and legislators’ official terms expire in a few months.

Throughout, the 36-year-old Guaidó has admitted no mistakes, and neither he nor his backers in Washington have offered a fresh strategy to rescue their floundering battle to unseat Maduro. The Trump administration has continued to pile economic and travel sanctions onto members of Maduro’s inner circle, but so far with little effect.

“We’re up against a dictatorship,” Guaidó said in an interview with The Associated Press. “I think that is central.”

Guaidó said he remains focused on winning over the military, the linchpin of support for Maduro, and he dismissed the idea of further negotiations with the socialist administration—talks his side says Maduro has used to defuse protests without making concessions.

He also said he favors boycotting legislative elections in 2020 as long as the electoral board running the vote remains packed with Maduro loyalists.

Still, Guaidó insists his domestic and international support will only grow.

In this December 17, 2019 photo, Venezuelan opposition leader and self-proclaimed interim president Juan Guaidó speaks during an extraordinary session at the National Assembly in Caracas, Venezuela. (AP Photo/Matías Delacroix)

Guaidó, the hand-picked successor to then-detained opposition leader Leopoldo López, leaped onto the stage last January at a dark moment in the once-wealthy nation’s history. Despite sitting atop the world’s largest proven oil reserves, gasoline shortages plague the nation, most homes don’t have reliable drinking water or electricity and there are shortages of food, medicine and spare parts.

Roughly 4.5 million people have left the country, figures that rival mass migration from war-torn Syria.

Seizing on the nation’s desperation, Guaidó drew masses into the streets 11 months ago when he claimed to be Venezuela’s legitimate interim president after congress declared Maduro’s re-election illegal.

The bold move overnight turned Guaidó into the nation’s most-popular politician since Chavez burst onto the political scene in the early 1990s. More than 60% of Venezuelans viewed him favorably in February, according to Caracas-based polling firm Datanalisis, with many believing he would rid them of Maduro within three months.

“Guaidó became the outsider that people were looking for to face Maduro,” said Datanalisis’ president Luis Vicente León. “A kind of hope formed around him.”

Today that support has sunk by 20 percentage points, said León, a sign that Venezuelans are starting to think that removing Maduro from power may be impossible.

Maduro, whose approval ratings in the other polls have dipped closer to 10%, has proven more resilient than many expected.

Venezuela’s oil production has inched up for the second consecutive month after crashing to a seven-decade low under U.S. sanctions, and shoppers are increasingly pulling U.S. dollars from their wallets—a sign the economy is bouncing back, or at least stabilizing, due in part to an easing of currency controls that the government had earlier resisted.

In this December 19, 2019 photo, a man sitting on a bus looks at a mosaic of late leader Hugo Chávez, left, and of Venezuela’s President Nicolás Maduro, right, in Caracas, Venezuela. (AP Photo/Matías Delacroix)

Maduro also appeals to many Venezuelans who still mistrust an opposition seen as corrupt and elitist and who honor the memory of Chavez, who died before the economic collapse hit home.

Vice President Delcy Rodríguez declared the “attempted coup d’etat” led by President Donald Trump a failure as she spoke last week to the National Constituent Assembly, a body the government created to bypass the opposition-dominated congress.

“They don’t understand what’s happening within Venezuela,” Rodríguez said. “They follow Hollywood scripts but don’t have an ending our political project.”

Maduro has agreed to several rounds of negotiations over the years, including some sponsored by the Vatican and the government of Norway that raised hopes of a breakthrough to the political crisis, only to have them fall apart.

Accelerating the opposition’s downfall have been revelations of corruption.

The National Assembly that Guaidó heads has suspended seven opposition lawmakers —three of them from Guaidó’s Popular Will party— who are accused of lobbying on behalf of businessmen who were under investigation both in Venezuela and the U.S. for allegedly defrauding Maduro’s landmark food subsidy program.

In January, the National Assembly must decide whether to extend Guaidó’s tenure, and he said he is confident he has the backing to be re-elected as assembly president. Analysts say appointing any alternative would be devastating for the opposition.

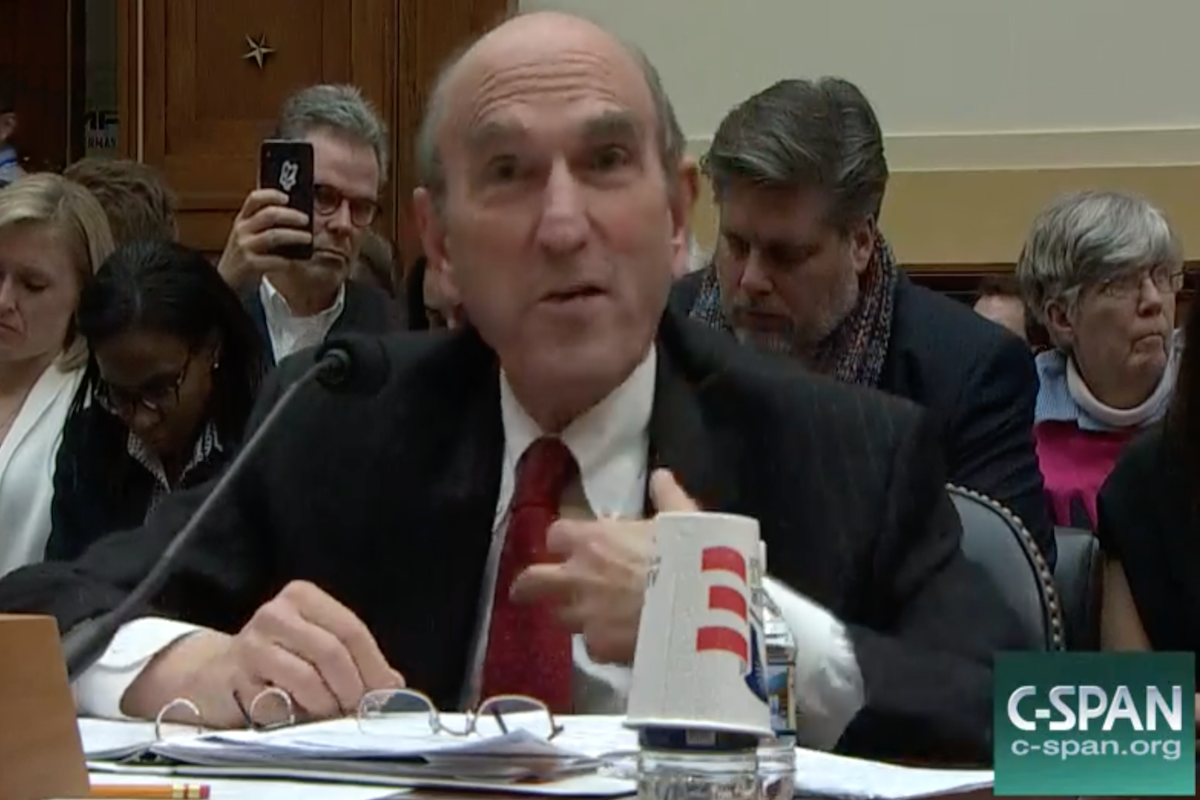

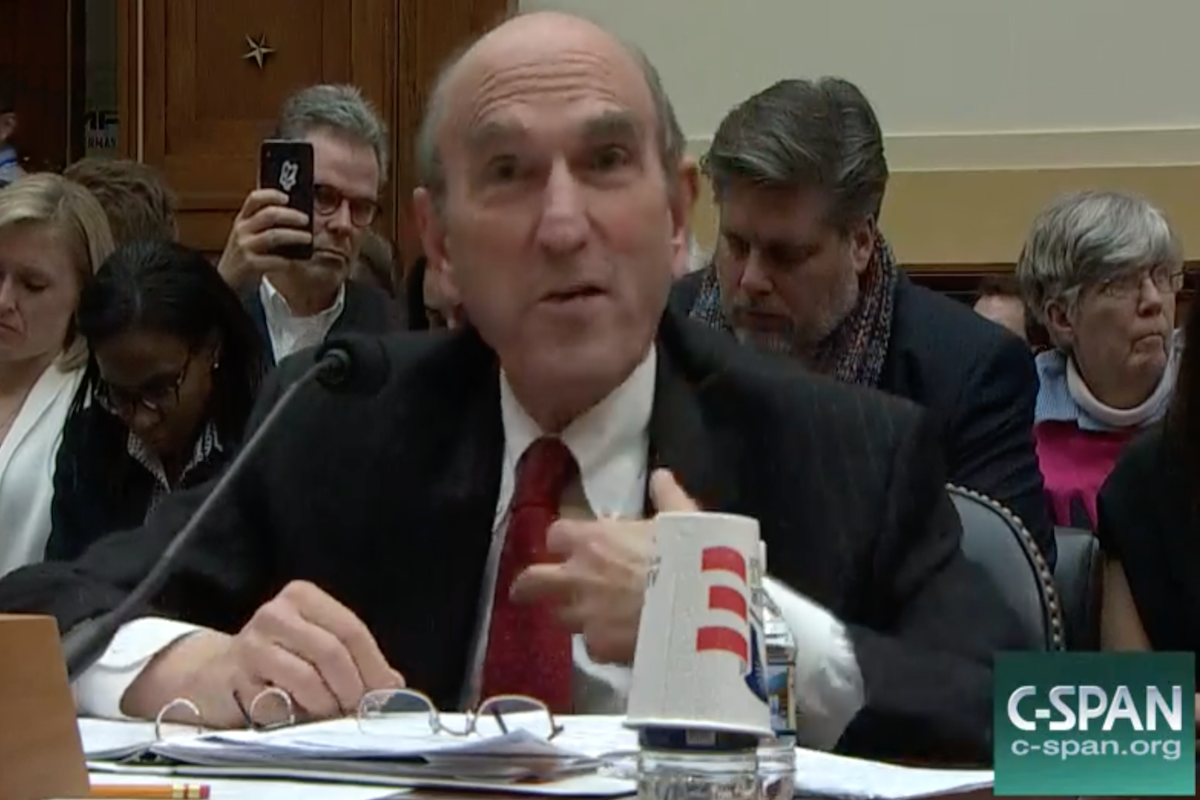

Adding to his obstacles, Maduro’s government has stepped up its campaign to undermine the opposition, offering large bribes to lawmakers to vote against Guaidó, Elliott Abrams, the U.S. special envoy to Venezuela, told reporters in Washington on Friday.

Elliott Abrams testifying earlier in 2019 (C-SPAN)

Maduro’s government also recently charged four opposition lawmakers with treason and rebellion, bringing to roughly 32 the number of legislators who have been detained, forced into exile or had their constitutional immunity from prosecution revoked. Opposition leaders said a special police force on Friday detained lawmaker Gilber Caro, in what Guaidó called a ¨kidnapping.”

U.S. diplomats say Guaidó continues to have their full support, and they plan to further increase diplomatic and economic pressure on Maduro to hold new elections. They are urging European leaders to follow the U.S. example.

“The Maduro regime fears free elections,” Abrams said. “So pressure is needed to get the free elections that can bring Venezuela out of the repression and poverty that have been the hallmark of the Maduro for years.”

Palacios, whose faith in Guaidó has long since faded, said he hopes somebody steps forward to lead Venezuela out of its crisis.

He has turned his back on Guaidó’s call for more street protests and instead has buried himself in running his business, which caters to the few remaining adventure tourists. He is also caring for his parents and ailing grandmother, who suffers Parkinson’s disease and struggles to find medicine she needs.

“Sadly, you can’t make any plans for the future because there’s no economic stability,” said Palacios, dismayed by the opposition’s fading show of strength. “I’m annoyed. It’s just more of the same.”

***

Scott Smith on Twitter: @ScottSmithAP