If art is an expression of the artist, Raul Pizarro’s work can be best described as a multidimensional evolution.

Living with a form of muscular dystrophy, Pizarro reinvents his painting techniques with each physical challenge brought on by the various stages of muscle loss.

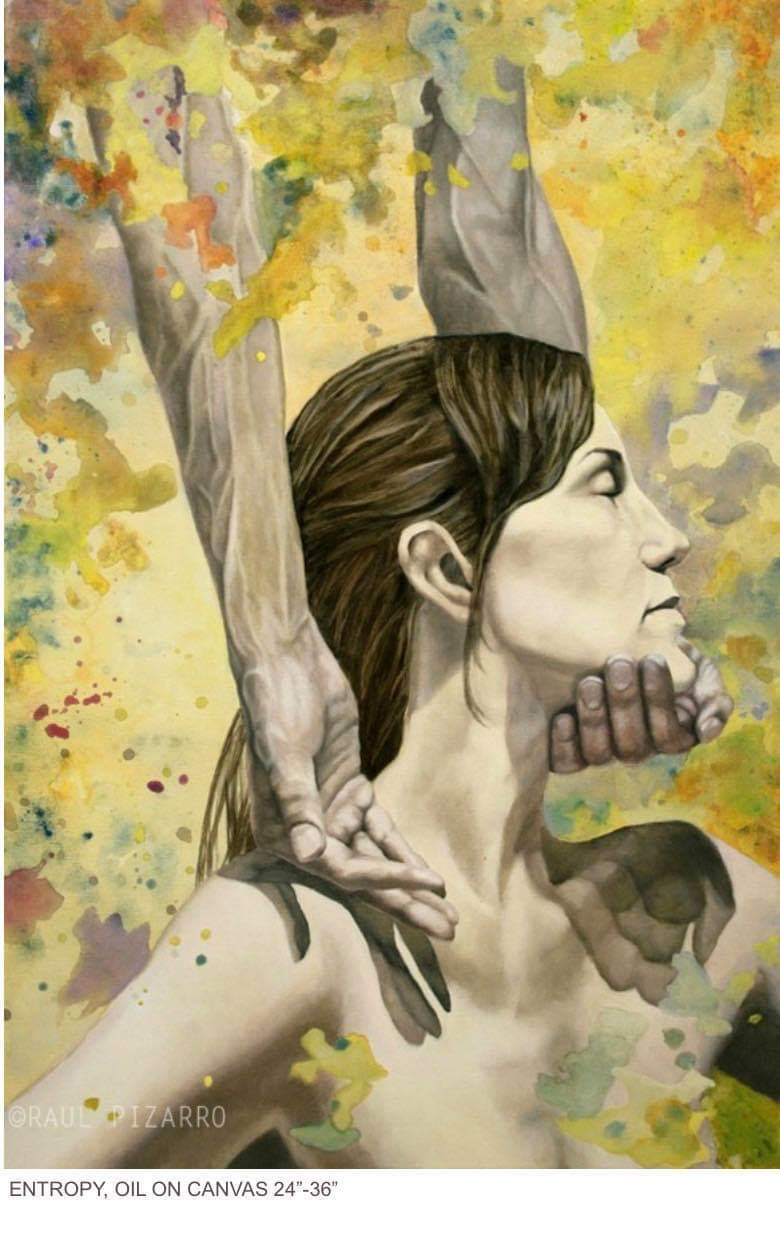

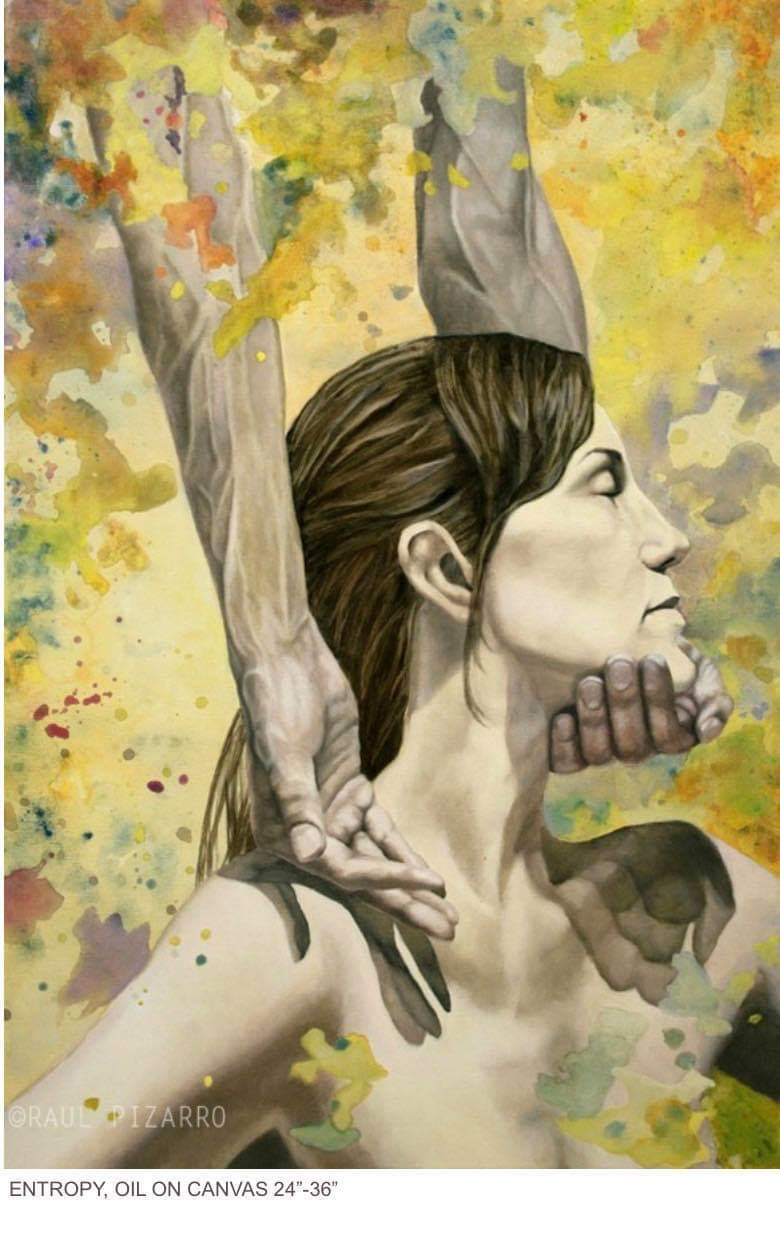

Courtesy of Raul Pizarro

“I paint every day, knowing that every ounce of strength I put into applying each brush stroke is the measure of life,” Pizarro told Latino Rebels. “My muscles aren’t vanishing, they are transforming into permanent echoes on canvas.”

Born in Mexicali, México, Pizarro calls Southern California home. Living on the fringe of Los Angeles County, he reflects on his early childhood and introduction to art.

“My parents wanted to make sure we spoke Spanish so it was all I knew at that age,” he recalled. “When I went to school, all the teachers and students spoke English. Because of the language barrier, my teacher would give me paint to keep me busy while the others learned about colors, numbers, and letters. Drawing was my first bridge to others. I drew things I enjoyed like swinging and the other kids would see it and understand. It’s how we would learn to play. This was my first connection to art.”

Pizarro continued drawing through his teenage years but due to the costs of art supplies, did not paint often.

“My parents were struggling to keep us fed, with a warm roof over our heads,” Pizarro said. “I started painting because one of my teachers gave me a box of art supplies. As a young adult, I started to really dedicate myself to art and exploring different ideas and mediums… I was finding my voice.”

Pizarro, 44, is passionate about immigration rights and queer rights. He describes his art as a timeline that varies by series, with his earlier work being experimental.

Raul Pizarro (Courtesy of Raul Pizarro)

“It was the time I was coming out as queer to myself and also when I left the church I was raised in,” he said. “It was evangelical and just didn’t make sense to me most of the time, so it took some time to come to terms with that truth. One of my first series is titled “Songs For A Deaf God,” which I worked on for nearly 11 years. It’s structured around identity, [while] a few [others] were about gender, and a few others around mental illness.”

Pizarro’s most recent series is mostly focused on bears. He began painting it for his nephew who was non-verbal until he was three years old. The relationship he has with his nephew is, as he describes, the closest to having a bond to that of with ones own child.

“The paintings in that series are moments where I rediscovered joy through his eyes,” he explained. “Then I began to explore my own truths through the bears. They are important to me as they are both fierce and nurturing. That is what the painting process has been for me as well.”

Art imitating life is natural here. In terms of how Pizarro’s art is reflective of his disability, nearly all of his paintings are tied around how his body is continuously changing. Some more explicit than others.

“There is a painting titled ‘Vínculo’ [Spanish for ‘bond’] that I painted when I was really ashamed about the way my body was starting to look, emaciated with contractures on my limbs,” Pizarro said. “In the painting there are identical beings facing each other with closed eyes, both equally emaciated with one touching the other’s face while the other touches the other’s chest. It was a time when I wanted to connect and heal the way I viewed myself, and accepting my life just as it was.”

Pizarro uses a power wheelchair that has a lift and a custom easel that moves up, down, left, right and tilts towards him with a remote control. When using both the lift and easel, it makes working on larger pieces possible.

Courtesy of Raul Pizarro

“With this set up I’ve been able to create paintings larger than I had before,” Pizarro said. “The largest piece I have worked on is six feet tall.”

Pizarro’s influences are varied with most of them consisting of moments of reflection and acceptance. His nephew and niece are a big influence on the latest bear series.

“Seeing them discover things we’ve forgotten or taken for granted as adults is an unexpected gift,” he noted.

What does Pizarro’s art mean to him?

“My life is art. I leave all of my strength in it, all of my joy, sorrow and truths. I store all of those moments on canvases.”

***

Val Vera is a writer who covers disability culture, lifestyle, politics, law, and technology. He tweets from @ValVeraTX.

[…] This article was originally published on Latino Rebels. Read the original story here. […]

[…] Val Vera with a well-crafted article for Latino Rebels… […]