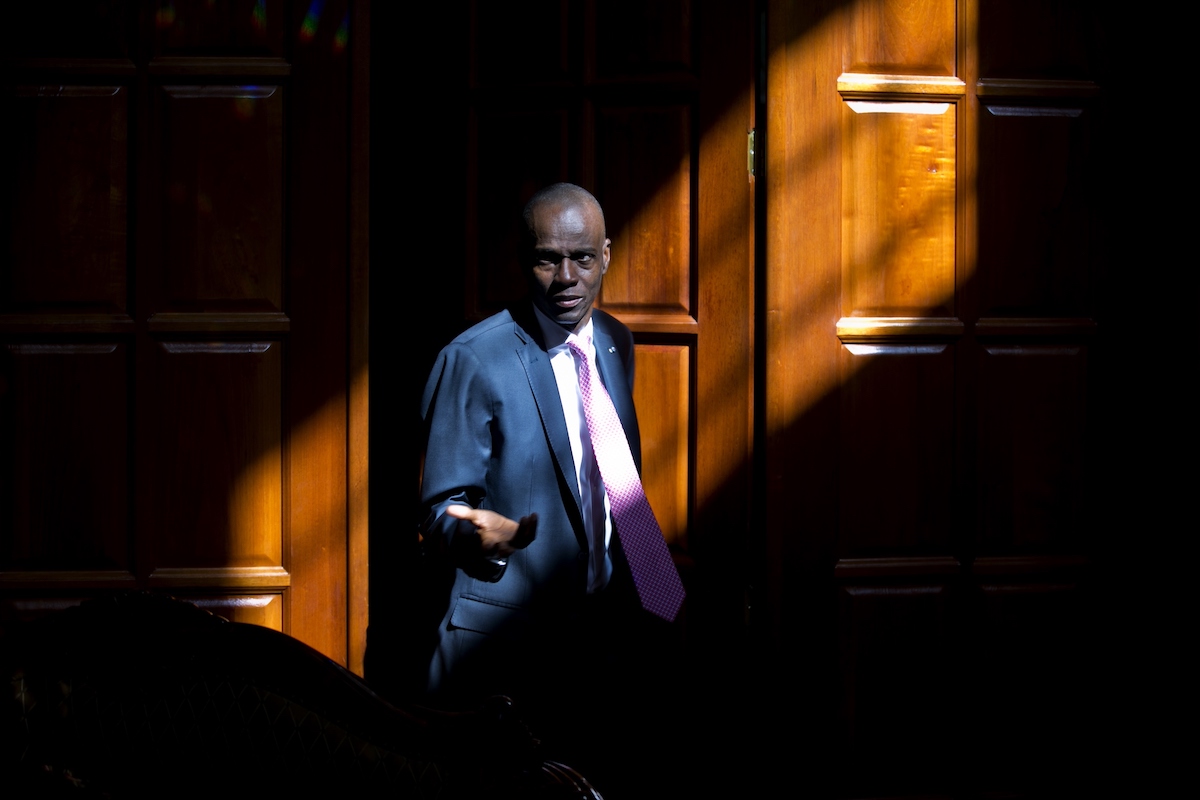

Haiti’s President Jovenel Moïse arrives for an interview at his home in Petion-Ville, a suburb of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Friday, February 7, 2020. (AP Photo/Dieu Nalio Chery)

By MICHAEL WEISSENSTEIN, Associated Press

PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti (AP) — President Jovenel Moïse said Friday that he is optimistic that negotiations with a coalition of his political opponents will succeed in forging a power-sharing deal to end months of deadlock that have left Haiti without a functioning government.

In an interview with The Associated Press, Moïse laid out his bargaining position in the talks that began last week in the mission of the papal envoy to Haiti with political opponents and some civil society groups. He said he would accept an opposition prime minister and a shortened term in office, but only after adoption of a constitutional reform strengthening the presidency.

Moïse said his efforts to improve living conditions for Haiti’s 11 million people had been thwarted during his first three years in office by the constitutional requirement that the National Assembly must approve virtually all significant presidential actions.

He said he would serve only a single term in office so he would not personally benefit from the powers of a stronger presidency.

“It makes me optimistic to see my brothers and sisters from the political opposition, civil society and religious groups,” he said. “I think we’re at a crossroads.”

Moïse is a former banana farmer who won 56% of the vote against three opponents in the 2016 election. He made some progress on rural infrastructure projects during his first two years in office. Then the end of subsidized Venezuelan oil aid to Haiti fueled chaos in the Western Hemisphere’s poorest nation.

Without the help, the economy shrank, and investigations found questionable spending of hundreds of millions of dollars over the years in aid from the Petrocaribe program run by Venezuela. Protests began over the Petrocaribe misspending and protests snowballed until Moïse’s opponents waged a near-total lockdown of Haiti’s capital for three months last fall.

Protests were accompanied by a constant blocking of Moïse’s agenda in the National Assembly. A small group of opposition legislators blocked Moïse proposals with tactics ranging from filibusters to throwing furniture inside the Senate chamber or calling supporters to block governing party senators access to the building.

The country was unable to organize legislative elections and the National Assembly shut down last month, leaving Moïse without a constitutionally recognized government. He says the constitution allows him to rule by decree with legislative approval but he is choosing not to in order to forge national unity.

Observers say developed nations that provide Haiti with most of its state budget are highly reluctant to keep funding a government that could be accused of moving toward dictatorship.

Haiti’s 1987 constitution was drafted after the end of three decades of dictatorship and aims in part to prevent the emergence of another strongman by sharply limiting presidential powers.

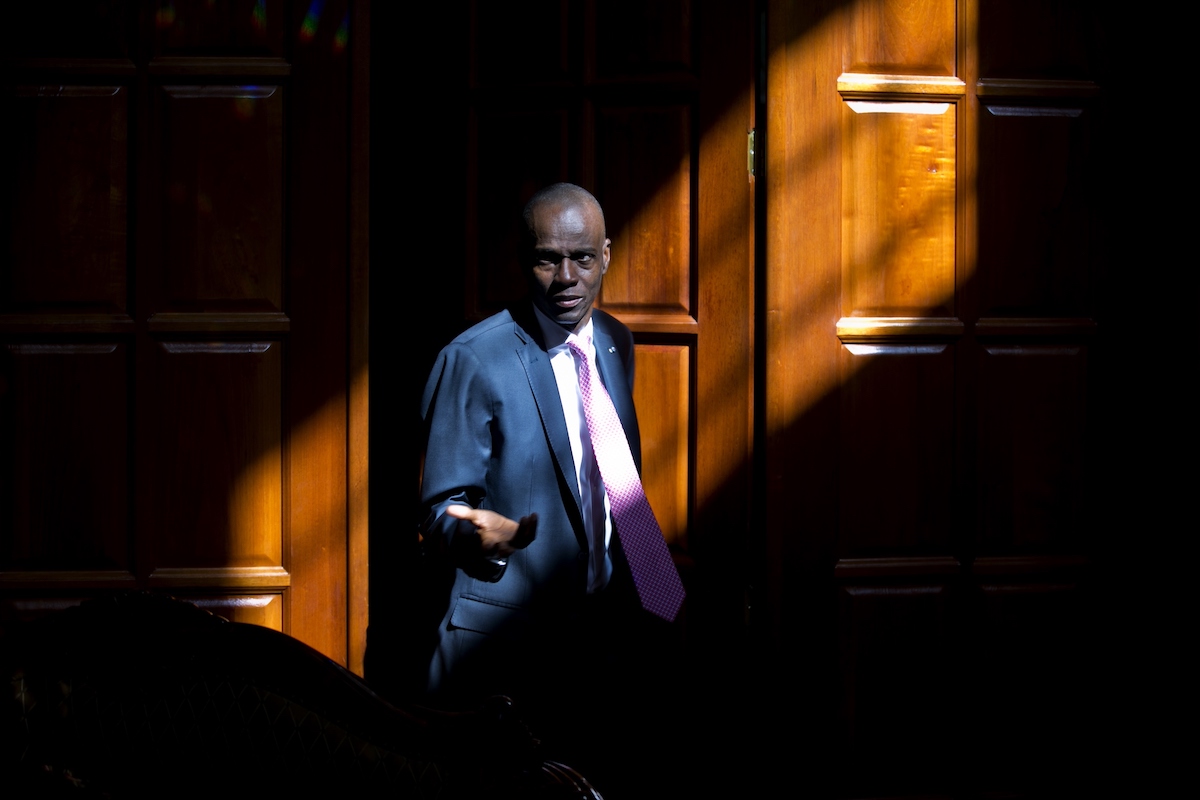

“The 1987 constitution took all the power out of the president’s hands. The president has zero power and the people demand everything from the president of the republic,” Moïse told AP in the foyer of his home in the hills above Port-au-Prince.

Haiti’s President Jovenel Moïse peaks during an interview with The Associated Press in his home in Petion-Ville, Haiti, Friday, Feb. 7, 2020. ( AP Photo/Dieu Nalio Chery)

Moïse said he wants a new constitution to stipulate that presidential proposals automatically pass if the National Assembly does not vote them up or down within 60 days.

He also wants all political terms to last five years. Senate terms currently range from two to six years, depending on a variety of factors, leading to constant churn and campaigning in a country where widespread insecurity and corruption make elections difficult to organize.

Convening a constitutional assembly to rewrite the charter would almost certainly take most of Moïse’s remaining two years in office.

Most of the political opposition has demanded that Moïse significantly cut his time in office, with some demanding his immediate resignation and others asking for him to hand over power early next year.

He said negotiations would succeed “if there’s good will on the part of the people involved to find a way forward with a realistic calendar.”

“You can’t say you’re going to carry out these reforms in two months,” he said.

A coalition of relatively moderate opponents and civil society groups were unable to reach a deal with Moïse’s representatives last week at the papal nunciature. Another group of hard-line opponents did not participate.

Moïse said he thinks he can reach a deal with enough opponents to move the country forward.

“‘We need to all get together and forge a deal, even if that deal isn’t accepted by everyone,” he said. “You’ll have radicals, extremists who won’t sign, who won’t accept it, but that won’t kill the republic.

“I’m not hung up on finishing my term. I’m hung up on making reforms,” he said.

[…] Haitian President Lays Out Terms for Deal With Opposition via @AP https://www.latinorebels.com//2020/02/09/haitianpresident/ … […]