This February 13, 2020 photo shows a memorial for Juan Carlos Medina Serrano in his family’s living room, the day his remains were buried, in Irapuato, Guanajuato state, Mexico. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

By MARK STEVENSON Associated Press

IRAPUATO, Mexico (AP) — Mexico’s drug war has long played out in dusty northern border cities or the poppy fields of its southern mountains, but now the killings have moved to the conservative industrial heartland state of Guanajuato, creating a strange duality: shiny new auto plants and booming foreign investment even as the state becomes Mexico’s most violent.

Gleaming four-lane highways pass sprawling automotive plants and people carry yoga mats and sip chai at outdoor cafes in upscale suburbs. Several new luxury subdivisions spring up every year in the state’s colonial city of San Miguel de Allende, which is popular with foreigners.

But Guanajuato’s visible wealth contrasts with its grim headlines: Seven men lined up in a junkyard and shot. Gunmen open fire in a roadside eatery, leaving nine customers dead in a lake of blood. Seven people are gunned down at a street-side taco stand.

That was just one week in late January when the government said Guanajuato, which has around 5% of Mexico’s population, suffered 20% of its homicides. In 2019, the state had a homicide rate of about 61 per 100,000 inhabitants, making it Mexico’s most violent.

In this February 13, 2020 photo, Alondra Mora wipes away a tear as she talks about her late husband, Miguel Flores Lopez, during an interview in the two-bedroom home where they lived with their four children, in Irapuato, Guanajuato state, Mexico. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

It is not the auto plant executives or foreigners who are getting killed, as local officials like to point out. The violence arises from a bloody war between the home-grown Santa Rosa de Lima gang and the powerful Jalisco New Generation Cartel, which is waging a major offensive to move into Guanajuato. The state is attractive to drug cartels for the same reason it is to auto manufacturers — road and rail networks that lead straight to the U.S. border.

The head of the state’s security commission, Sofia Huett, defines Guanajuato’s odd dynamic this way: “Sometimes people confuse the violence with a lack of public safety in Guanajuato, and in fact they are two different things.”

What Huett apparently means is that what officials define as decent, law-abiding people aren’t being killed. Criminals are killing criminals is a refrain repeatedly heard, along with the belief that most of the criminals are from outside the deeply Roman Catholic state — a reference to the invading gang from Jalisco and violence spilling over from Michoacan.

“The murders in Guanajuato are not killings carried out during robberies,” Huett said. For example, she notes that muggings in the state are among the lowest in the nation. “The majority of crimes, the ones that most affect inhabitants, are well below the national average.”

Most investors — and even local officials — seem prepared ignore the wave of homicides as just gang members killing gang members.

“There are victims who are caught in the crossfire, and they are the ones I really feel sorry for,” said Ricardo Ortiz, mayor of the city of Irapuato. “But we can’t be expected to protect people who are doing bad things.”

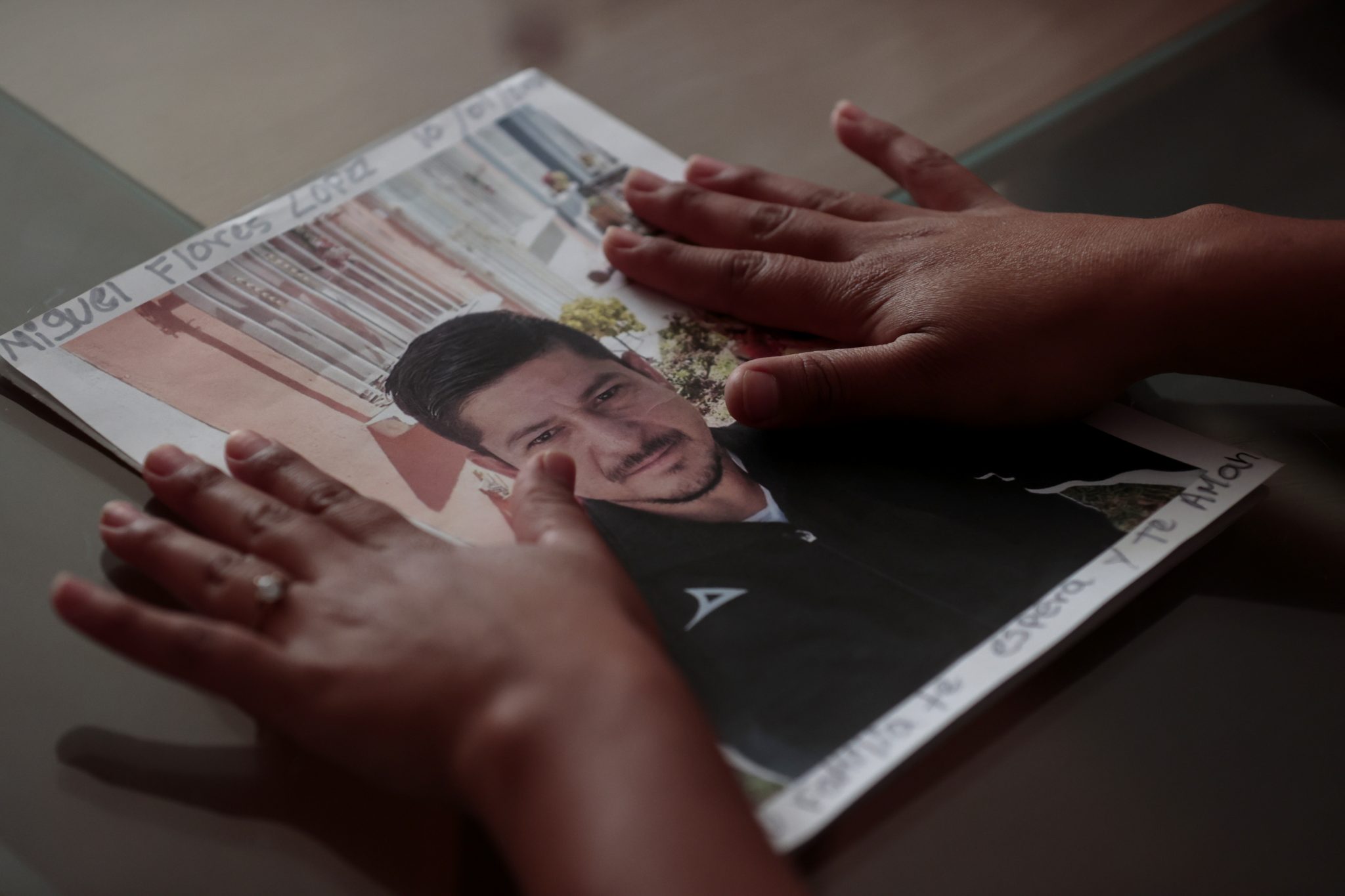

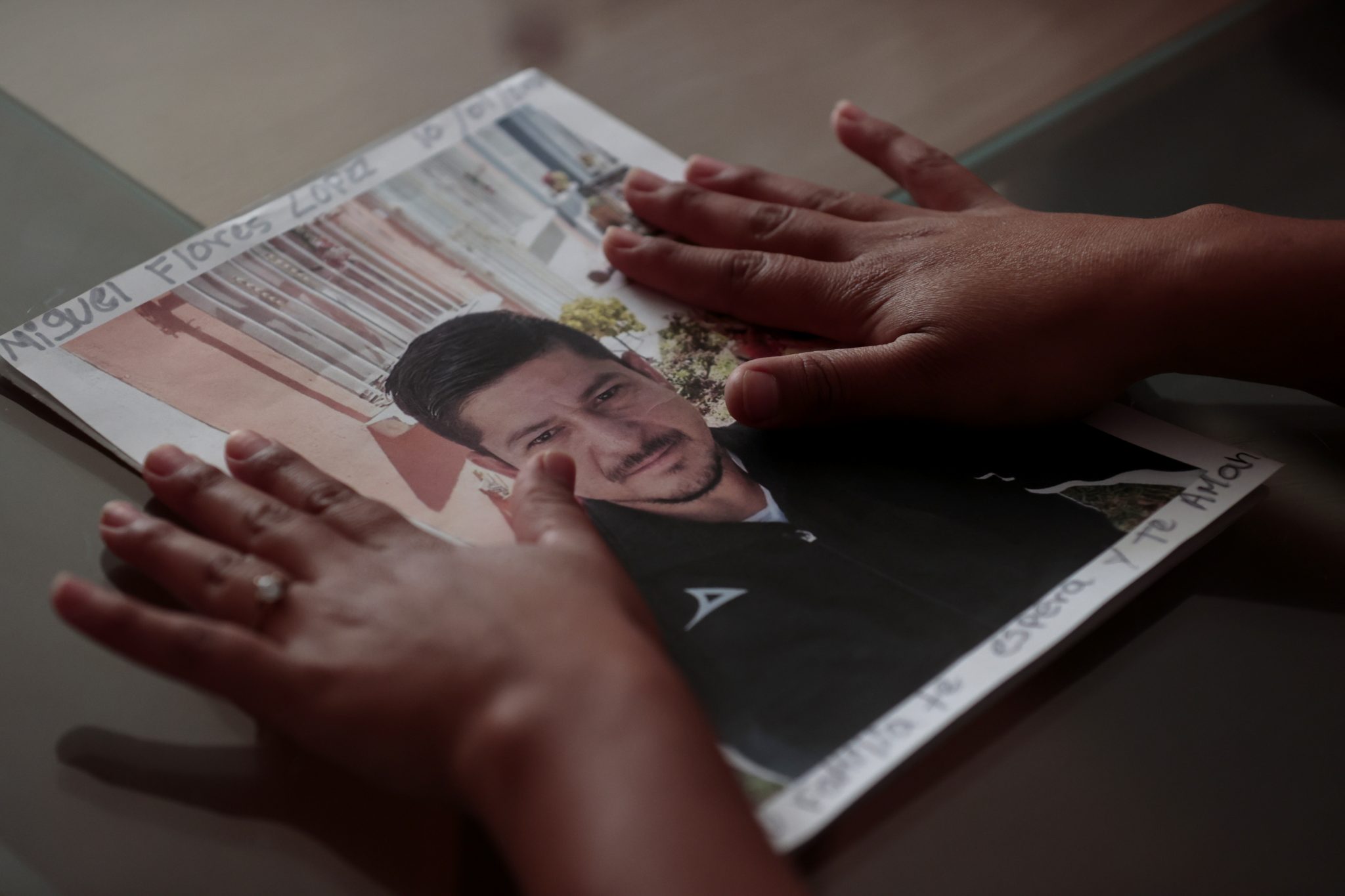

In this February 13, 2020 photo, Alondra Mora runs her hands over a picture of her late husband, Miguel Flores Lopez, as she talks about his disappearance, during an interview in the two-bedroom home where they lived with their four children, in Irapuato, Guanajuato state, Mexico. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

Moises Guerrero, mayor of Apaseo El Grande, where a new, $1 billion Toyota pickup assembly plant opened this month, also minimizes the spillover of the gang war onto citizens and investors. Referring to targeted killings by cartel gunmen, Guerrero said: “They don’t make mistakes. They go after the person they are after.”

Huett says that “between 80 and 85% of the homicides in Guanajuato are related to criminal activities.” She also points the finger at people from out of state. “If we look at 10 people who have been arrested, often of those 10 only one or two of the suspects come from Guanajuato.”

That kind of statement has caused untold grief for crime victims like Alondra Mora, whose husband, Miguel Flores Lopez, disappeared Jan. 10 after he was dragged from his taxi by armed men. Mora chokes up as she shows a photo of him in the humble house they rented on the outskirts of Irapuato. The house is so tiny that visitors’ knees touch when they sit in armchairs in the living room.

Mora and her husband came to Guanajuato from their native gang-plagued state of Michoacan in mid-2019, looking to build her shoe-retail business in what they viewed as a more prosperous state.

“They have to stop discriminating,” Mora said of Guanajuato state officials. “If people with money are kidnapped, how long is it before they are released? One day? But for those who don’t have money, it costs them their lives, because they don’t even look for them.”

Mora experienced first-hand Guanajuato’s willingness to ignore the killings of poor migrants from other states.

“When I went to file the missing person report, the guy who took my statement was making fun of us for being from Michoacan, saying: ‘Why did you have to come here?'” she recalled.

Prosecutors even asked her to investigate the case for herself, she said. The couple’s bank debit card had been used after her husband’s disappearance, and she had to ask the bank where the withdrawal was made. Prosecutors never checked phone records, apparently eager to write it off as a gang killing.

In this February 12, 2020 photo, soldiers patrol a neighborhood in Irapuato, Guanajuato state, Mexico. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

“As far as they’re concerned, everybody who disappears was involved in something bad,” Mora said.

Maria Guadalupe Gallardo López is one of approximately 80 activists looking for missing relatives in the Guanajuato as part of the group “A Tu Encuentro,” roughly “Looking for You.”

Armed men took her husband, Juan Carlos Medina Serrano, from their house Dec. 3. A few days later, authorities found 19 rotting bodies buried in a backyard in a nearby town, but it took two months for them to notify Gallardo Lopez that her husband had been among the bodies. He was identified by genetic testing.

With the dismembered body returned to the family in a sealed box, the family quickly held a poverty-stricken wake for him, with a few candles next to a cross of quick-lime sprinkled on the bare floor of their dwelling. On a table, a candle burned before a figure of St. Judas Tadeo, Mexico’s patron saint of lost or desperate causes popular in the underworld.

Gallardo López can’t, or won’t, explain what her husband did for a living. “He sold things … on the street,” she said vaguely. But she also said that if police and prosecutors keep writing off deaths like her husband’s, it won’t be good for anybody.

“They have to do their job. If they don’t take action, if they don’t do their job, they are going to keep finding people like this,” she said. “I don’t want anybody to have go through what I did.”

While families like hers suffer, many in Guanajuato have lives largely untouched by the violence.

Jorge Barroso, the young marketing director at Tenis Court athletic shoes, whose factory is in Guanajuato’s shoe-making capital of Leon, says he lives without fear, going out to restaurants or clubs as he wishes.

“The truth is, I don’t even perceive it,” Barroso said. “When I read about this stuff in the newspapers, it’s like they’re talking about another state.”

Gov. Diego Sinhue says “Guanajuato is not Sinaloa,” the Mexican state that became famous as the cradle of the drug cartel of the same name.

But like Sinaloa, Guanajuato has a home-grown gang, the Santa Rosa de Lima cartel. The gang, named after a small farming hamlet, got its start robbing freight trains and then turned to stealing gasoline and diesel from an oil refinery in the city of Salamanca.

In this February 10, 2020 photo, a policeman drives past town hall in Apaseo El Alto, Guanajuato state, Mexico. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell)

When the government cracked down on fuel theft, the Santa Rosa gang turned to extorting protection payments from local businesses, going industry by industry. First they shook down tortilla shops, then auto dealerships and real estate agents. Now they are apparently focusing on bars and nightclubs.

Part of Guanajuato’s odd reality stems from its success at cracking down on crimes that hurt businesses together with its inability to stop the drug gang war.

Theft from railroad cars — which only a few years ago started to affect shipments of tires and auto parts — fell dramatically after soldiers and police were posted on the rail lines, and huge billboards were put up along the tracks saying : “Crackdown on railway theft: prison terms of up to 17 years. This means you. Jail without bail.”

In other parts of Mexico, protesters, pressure groups or cartel gunmen regularly block roads and train tracks, but that doesn’t happen in Guanajuato. While the state isn’t very strenuous in investigating homicides, protesters are hit with the toughest possible charges, including terrorism.

“Here, there are no road blockades by protest groups or criminals, and in the end that is attractive for business,” said Huett, the security commissioner.

Last year, 79 police officers were killed in the state. To stem the onslaught, the federal government has made Guanajuato a priority, constructing some of the first National Guard barracks here.

Worst hit has been the town of Apaseo El Alto, where Mayor Maria del Carmen Ortiz took office after her husband — the leading candidate to fill the office — was shot to death in 2018. Between late 2019 and early 2020, her police chief, a town councilman and a police officer were shot to death.

“2018, 2019 were terrible years,” she concedes.