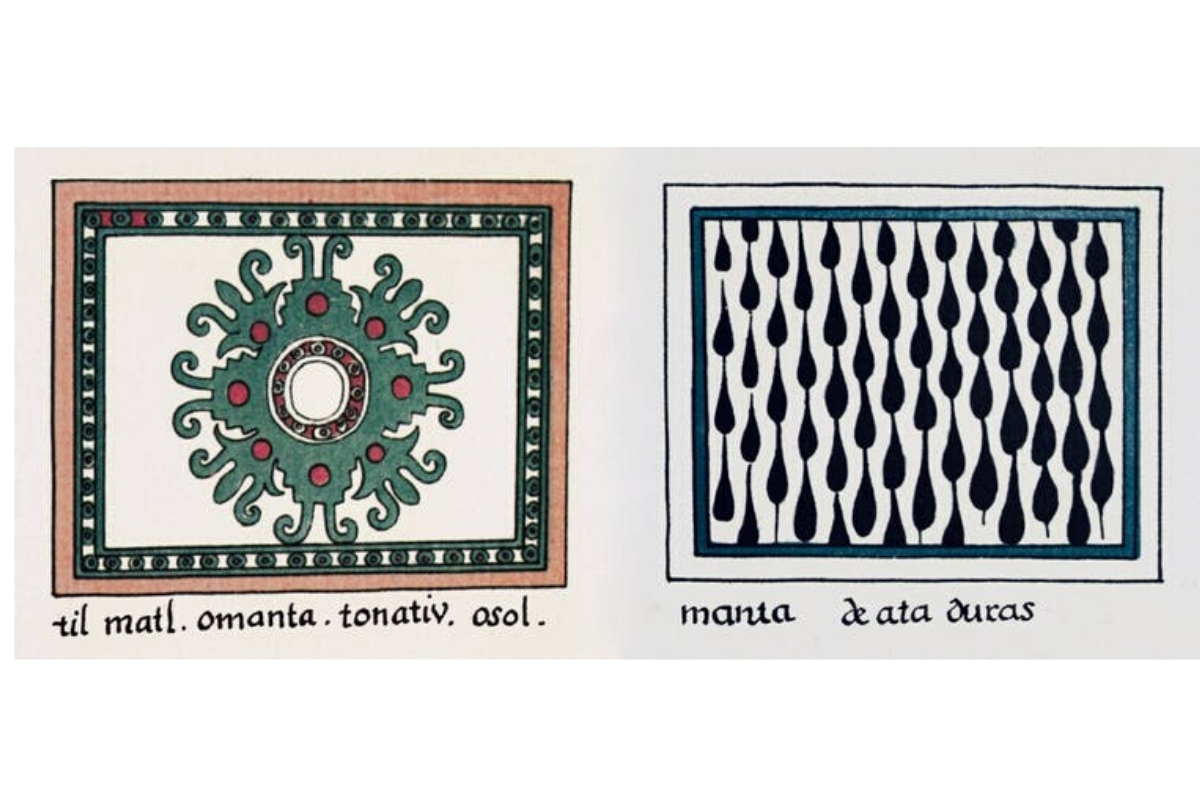

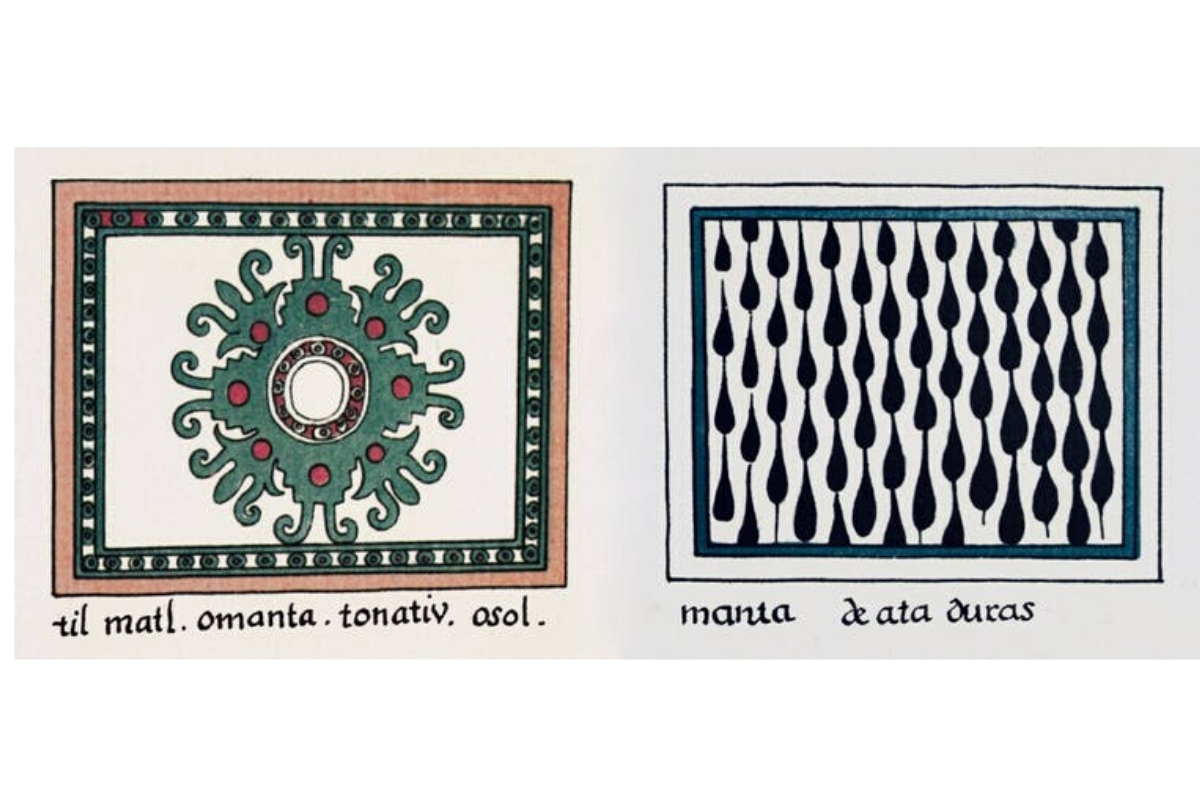

Ceremonial cape designs by Mexica (Aztec) artists who created the Codex Magliabechiano in the mid-1500s. Tonatiu (left) represents the sun deity and ‘ataduras’ (right) depicts bindings. (Via The Book of the Life of Ancient Mexicans, Z. Nuttall 1903, CC BY-NC)

By Felice S. Wyndham, University of Oxford

When infections sweep through human populations that have never experienced them before, the impacts are biological, social, psychological, economic—and all too often catastrophic. Many continue to loom large in our collective imaginations. The bubonic plague in Europe, smallpox in the Americas, and the Spanish flu are thought to have been the deadliest in history—and led to radical transformations in the societies they ravaged.

After Europeans invaded what became the Americas, from the 1490s onwards, most indigenous societies were decimated by waves of smallpox, influenza, measles, cocoliztli (a hemorrhagic fever), and typhus fever. We often think of this terrible episode —when colonialism caused novel diseases to run rife through the Americas— as being a thing of the distant past.

But it has, in fact, been an ongoing, if reduced, process over the last five centuries. The neocapitalist impetus for over-connectedness and exploitation of every last redoubt of South America’s heartland means that even the last holdouts are in danger of disease contact. As an ethnographer of ecological change, I have recorded testimonials from people who have survived harrowing contact with novel diseases of this kind in living memory.

Over the past decade, I’ve collaborated with Ei Angélica Posinho, an elder in an Indigenous Ayoreo community in northern Paraguay, South America, to document her life story. In the 1970s, when she was about 12 years of age, she lived through a novel virus infection among her people.

Ei Angélica Posinho being interviewed. (Photo courtesy of the author)

What follows is part of Ei’s story, shared with her permission—but many, if not all, Ayoreo elders of her generation have similarly tragic accounts.

A Story of Loss and Resilience

Ei, whose name means “Root” in the Ayoreo language, was born and grew up in a family whose mobile livelihood was built on gardening, fishing, hunting and gathering wild foods in “isolation” in their palm savannah, arid forest and wetland home.

Outsiders have called them “uncontacted peoples”, but most of the groups currently in isolation did interact historically with non-Indigenous groups and only later chose to physically distance themselves for protection. Ei’s extended family members, for example, studied and monitored the Paraguayan, Bolivian and Brazilian settlers who had been encroaching on their traditional territories for years, and purposefully avoided contact with them. They knew that the white settlers carried diseases that could devastate their families.

By the 1970s, however, Ei’s extended family group had been so pressured by settler attacks and inter-group conflict that they made the excruciating decision to trek the weeks’ distance to the nearest Mission to seek refuge. They mourned what was going to happen to them in advance, because they knew they would become ill. In Ei’s words:

After the decision to go live with the whites was made, my mama came home and my papa cried with her, his partner. It seemed as if we were going to die already. Lots of people cried. Everybody cried. They knew that with the missionaries many people would get sick and die. Most of my immediate family went with us as we left the bush at that time – we were eight people all together. Later, almost all eight of us died of sickness.

Ei’s mother and unborn sibling died soon after contact, as did her younger brother, contracting what was probably measles as soon as they interacted with the outsiders. Ei and her father became extremely ill, but survived, in part because:

The sickness didn’t get one of my brothers, so when my papa and I became ill, he was able to go to look for food. He saved us, bringing honey that we’d mix with water and drink. We didn’t want to eat the white people’s food as it smelled terrible to us. One time my brother brought us two armadillos, and my papa was so pleased. He said to me, ‘We are so lucky that your brother didn’t get infected with this illness. He has saved us.’

Many other Ayoreo families were not so fortunate. One of the deadliest aspects of diseases that affect everyone at once, such as in a new contact situation, is the breakdown of food procurement and care-giving. When this happens, even those who are not seriously ill may die from starvation or lack of basic care.

The Mexica Experience

Such devastation caused by novel diseases has a long history across the Americas. Soon after invading —Europeans arrived in the late 1400s and 1500s, and then again in numerous, subsequent waves— smallpox and other diseases spread across the two continents.

These first epidemics often arrived in Indigenous societies even before people there knew about the arrival of Europeans—the infections traveling in advance through existing networks of connection, from body to body, along Indigenous trade routes large and small.

In colonial Tenochtitlán (modern day Mexico City), oral histories were recorded with people who had survived the catastrophic epidemics of the 1500s. Bernardino de Sahagún and his team of Nahuatl-speaking Mexica scholars and scribes documented the experience in the 12th book of what became known as the Florentine Codex—or the Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España (General History of the Things of New Spain).

Living in a time of utter upheaval and catastrophic loss of life, these scholars wrote about the impact of smallpox. They specifically recorded how, in 1520, many died from the collapse of food and care systems:

There was much perishing. Like a covering, covering-like, were the pustules. Indeed many people died of them, and many just died of hunger. There was death from hunger; there was no one to take care of another; there was no one to attend to another.

A Long History of Physical Distancing

Ei has relatives who to this day live in isolation in the dry forests of northern Paraguay and eastern Bolivia—they likely number between 50 and 100 individuals, but no one knows for sure. There are probably about 100 additional groups in voluntary isolation in Brazil and Peru as well.

Year after year, these small groups have chosen to remain apart from white settlers. They harvest their traditional foods, trek their seasonal routes, speak their ancestral languages, and avoid contact with the myriad viruses circulating in the globalized, hyper-connected world of 2020.

Ei, having lived through a similar situation as a youngster, says that they are living on the run, afraid of the violence and disease invaders have brought. As many of us voluntarily isolate ourselves in our homes to protect against COVID-19, we are in a unique position to understand and respect Indigenous groups who choose to remain apart.

These last resisters of the 500-year narrative of epidemiological devastation have a fundamental right to sovereignty over their home territories. Indeed, many Indigenous groups are now blockading access to their communities, fearing COVID-19 infection. Meanwhile, governments from Brazil to the US have signalled that, in line with the historical patterns of the last 500 years, they may be poised to exploit the current pandemic to threaten indigenous land sovereignty.

But as we all now face an exponential wave of COVID-19 cases, let’s keep in mind that a key aspect of coming through events such as this with resilience is people’s ability to take care of one another and protect hard-won rights. Though industrialized nations’ food supply chains are vastly more extensive than those of the Ayoreo or the 16th-century Mexica, they are still fragile. Everyone needs nourishment and healthcare to fight off or recover from serious illness. And both are intimately coupled with social and political networks.![]()

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.