Members of the Massachusetts Asian American Commission protest on the steps of the Statehouse in Boston. (AP Photo/Steven Senne)

By Adrian De León, University of Southern California—Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences

In a recent Washington Post op-ed, former Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang called upon Asian Americans to become part of the solution against COVID-19.

In the face of rising anti-Asian racist actions —now at about 100 reported cases per day— Yang implores Asian Americans to “wear red, white, and blue” in their efforts to combat the virus.

Optimistically, before Donald Trump declared COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus,” Yang believed that “getting the virus under control” would rid this country of its anti-Asian racism. But Asian American history, my field of research, suggests a sobering reality.

A History of Anti-Asian Racism

Up until the eve of the COVID-19 crisis, the prevailing narrative about Asian Americans was one of the model minority.

The model minority concept, developed during and after World War II, posits that Asian Americans were the ideal immigrants of color to the United States due to their economic success.

But in the United States, Asian Americans have long been considered as a threat to a nation that promoted a whites-only immigration policy. They were called a “yellow peril:” unclean and unfit for citizenship in America.

In the late 19th century, white nativists spread xenophobic propaganda about Chinese uncleanliness in San Francisco. This fueled the passage of the infamous Chinese Exclusion Act, the first law in the United States that barred immigration solely based on race. Initially, the act placed a 10-year moratorium on all Chinese migration.

In the early 20th century, American officials in the Philippines, then a formal colony of the U.S., denigrated Filipinos for their supposedly unclean and uncivilized bodies. Colonial officers and doctors identified two enemies: Filipino insurgents against American rule, and “tropical diseases” festering in native bodies. By pointing to Filipinos’ political and medical unruliness, these officials justified continued U.S. colonial rule in the islands.

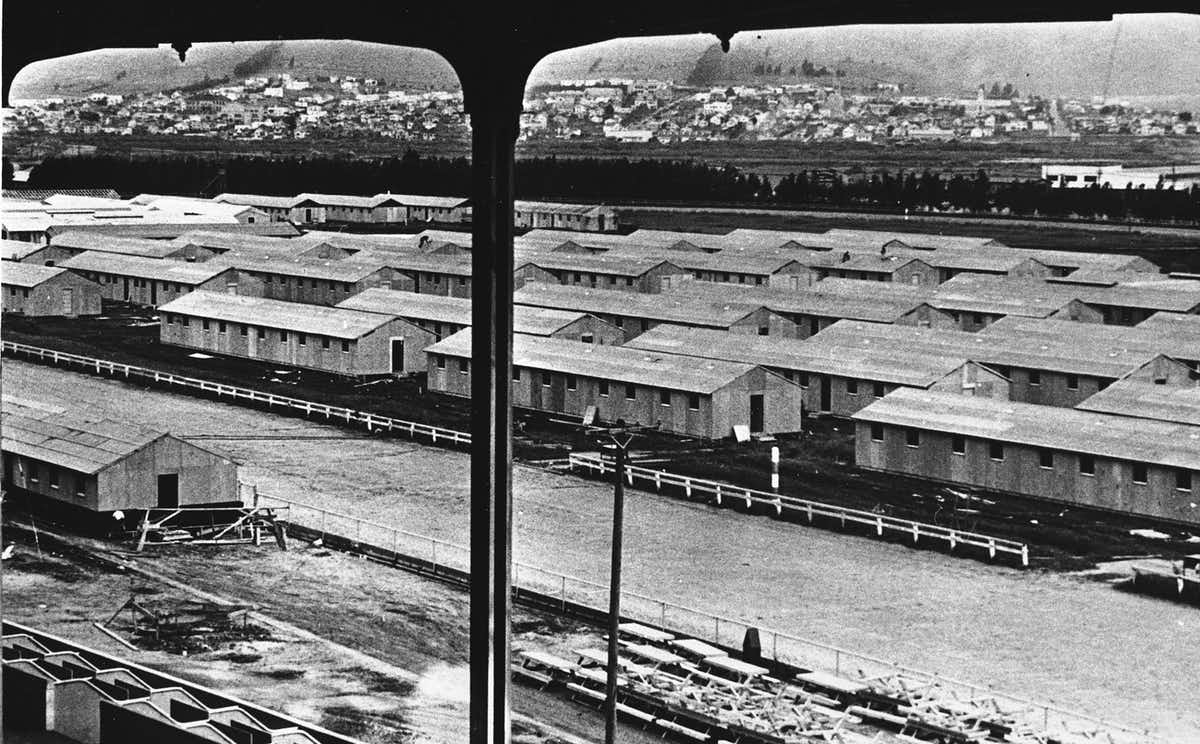

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 to incarcerate people under suspicion as enemies to inland internment camps.

While the order also affected German- and Italian-Americans on the East Coast, the vast majority of those incarcerated in 1942 were of Japanese descent. Many of them were naturalized citizens, second- and third-generation Americans. Internees who fought in the celebrated 442nd Regiment were coerced by the United States military to prove their loyalty to a country that locked them up simply for being Japanese.

In the 21st century, even the most “multicultural” North American cities, like my hometown of Toronto, Canada, are hotbeds for virulent racism. During the 2003 SARS outbreak, Toronto saw a rise of anti-Asian racism, much like that of today.

In her 2008 study, sociologist Carrianne Leung highlights the everyday racism against Chinese and Filipina health care workers in the years that followed the SARS crisis. While publicly celebrated for their work in hospitals and other health facilities, these women found themselves fearing for their lives on their way home.

No expression of patriotism —not even being front-line workers in a pandemic— makes Asian migrants immune to racism.

Making the Model Minority

Over the past decade, from Pulitzer Prizes to popular films, Asian Americans have slowly been gaining better representation in Hollywood and other cultural industries.

Whereas “The Joy Luck Club” had long been the most infamous depiction of Asian-ness in Hollywood, by the 2018 Golden Globes, Sandra Oh declared her now famous adage: “It’s an honor just to be Asian.” It was, at least at face value, a moment of cultural inclusion.

However, so-called Asian American inclusion has a dark side.

In reality, as cultural historian Robert G. Lee has argued, inclusion can and has been used to undermine the activism of African Americans, indigenous peoples and other marginalized groups in the United States. In the words of writer Frank Chin in 1974, “Whites love us because we’re not black.”

For example, in 1943, a year after the United States incarcerated Japanese Americans under Executive Order 9066, Congress repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act. White liberals advocated for the repeal not out of altruism toward Chinese migrants, but to advocate for a Trans-Pacific alliance against Japan and the Axis powers.

By allowing for the free passage of Chinese migrants to the United States, the nation could show its supposed fitness as an interracial superpower that rivaled Japan and Germany. Meanwhile, incarcerated Japanese Americans in camps and African Americans were still held under Jim Crow segregation laws.

In her new book, “Opening the Gates to Asia: A Transpacific History of How America Repealed Asian Exclusion,” Occidental College historian Jane Hong reveals how the United States government used Asian immigration inclusion against other minority groups at a time of social upheaval.

For example, in 1965, Lyndon B. Johnson’s administration signed the much-celebrated Hart-Celler Act into law. The act primarily targeted Asian and African migrants, shifting immigration from an exclusionary quota system to an merit-based points system. However, it also imposed immigration restrictions on Latin America.

A sign at the 2020 Lunar New Year Parade in Manhattan’s Chinatown. (Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

Beyond Model Minority Politics

As history shows, Asian American communities stand to gain more working within communities and across the lines of race, rather than trying to appeal to those in power.

Japanese American activists such as the late Yuri Kochiyama worked in solidarity with other communities of color to advance the civil rights movement.

A former internee at the Jerome Relocation Center in Arkansas, Kochiyama’s postwar life in Harlem, and her friendship with Malcolm X, inspired her to become active in the anti-Vietnam War and civil rights movements. In the 1980s, she and her husband Bill, himself part of the 442nd Regiment, worked at the forefront of the reparations and apology movement for Japanese internees. As a result of their efforts, Ronald Reagan signed the resulting Civil Liberties Act into law in 1988.

Kochiyama and activists like her have inspired the cross-community work of Asian American communities after them.

In Los Angeles, where I live, the Little Tokyo Service Center is among those at the forefront of grassroots organizing for affordable housing and social services in a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood. While the organization’s priority area is Little Tokyo and its community members, the center’s work advocates for affordable housing among black and Latinx residents, as well as Japanese American and other Asian American groups.

To the northwest in Koreatown, the grassroots organization Ktown for All conducts outreach to unhoused residents of the neighborhood, regardless of ethnic background.

The coronavirus sees no borders. Likewise, I think that everyone must follow the example of these organizations and activists, past and present, to reach across borders and contribute to collective well-being.

Self-isolation, social distancing and healthy practices should not be in the service of proving one’s patriotism. Instead, these precautions should be done for the sake of caring for those whom we do and do not know, inside and outside our national communities.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.