A man is disinfected by a health worker at the site where Guatemalans returned from the U.S. are being held in Guatemala City, Friday, April 17, 2020. Recently deported Guatemalans were placed in a athletic dorm facility to wait for the results of their tests for the new coronavirus. (AP Photo/Moisés Castillo)

By SONIA PÉREZ D., NOMAAN MERCHANT, BEN FOX and MICHAEL WEISSENSTEIN, Associated Press

GUATEMALA CITY (AP) — The Trump administration’s failure to test all but a small percentage of detained immigrants for the novel coronavirus may be helping it spread through the United States’ sprawling system of detention centers and then to Central America and elsewhere aboard regular deportation flights, migrants’ advocates said Friday.

The discovery of numerous COVID-19 cases among deportees on a flight that arrived this week prompted Guatemalan President Alejandro Giammattei to tell Guatemalans in a national address on Friday he was suspending such flights—a step his foreign minister had mentioned earlier to reporters.

Just 400 detainees in the U.S. out of more than 32,000 have been tested so far, according to testimony that Matthew Albence, the acting director of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, gave Friday to a congressional committee. The House Committee on Oversight and Reform said that Albence “also confirmed that ICE does not routinely test detainees before deporting them.”

More than 1,600 people deported from the United States to Guatemala over the last month were allowed to go home and into voluntary, unenforced quarantine. Fears are rising that it may have seeded the Central American nation with an untold number of undetected cases, increasing its vulnerability to the pandemic.

U.S. authorities took passengers’ temperatures before departure, and Guatemalan officials checked them for cough, fever and other symptoms on arrival. Those with possible COVID-19 symptoms had their mucous and saliva tested, but apparently healthy deportees underwent no testing and were allowed to head home even if they arrived on a flight with sick people.

Health experts say that was very risky because many infected people never show symptoms but are still highly contagious. Airport workers and at least one family member of a deportee have tested positive in Guatemala and are believed to have been infected by returned migrants, said Dr. Edwin Asturias, a University of Colorado epidemiologist who is from Guatemala and maintains close contact with health authorities there.

“It’s clear that deportees have been coming infected and without appropriate safety measures in the same airspace with other people,” Asturias said. “As we’re seeing, this type of deportation is producing contagion in Guatemala.”

Only on Monday did Guatemala begin testing every passenger who shared a flight with someone confirmed as positive. The same day, a plane carrying 76 people arrived on an ICE flight from Alexandria, Louisiana. A migrant who was feeling ill was tested and found to be infected, leading to tests for everyone else. Forty-three tested positive despite showing no signs of illness and are in medical quarantine, officials said.

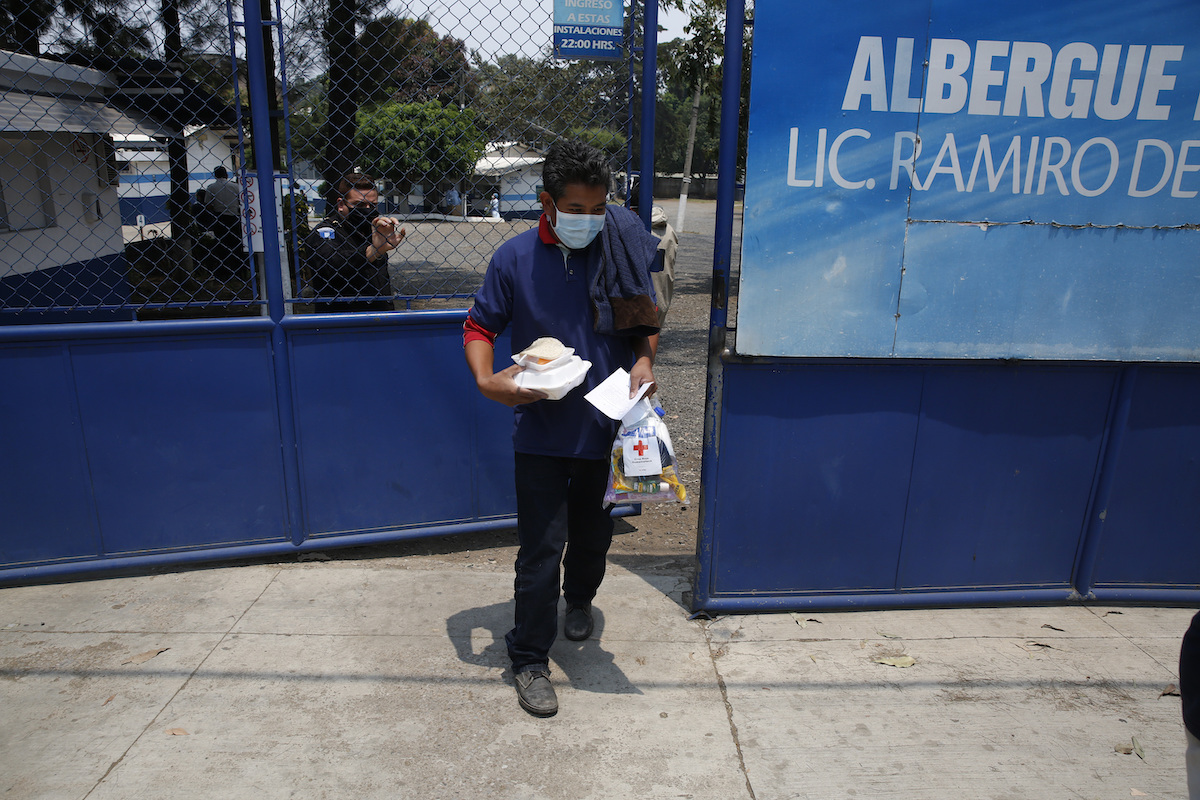

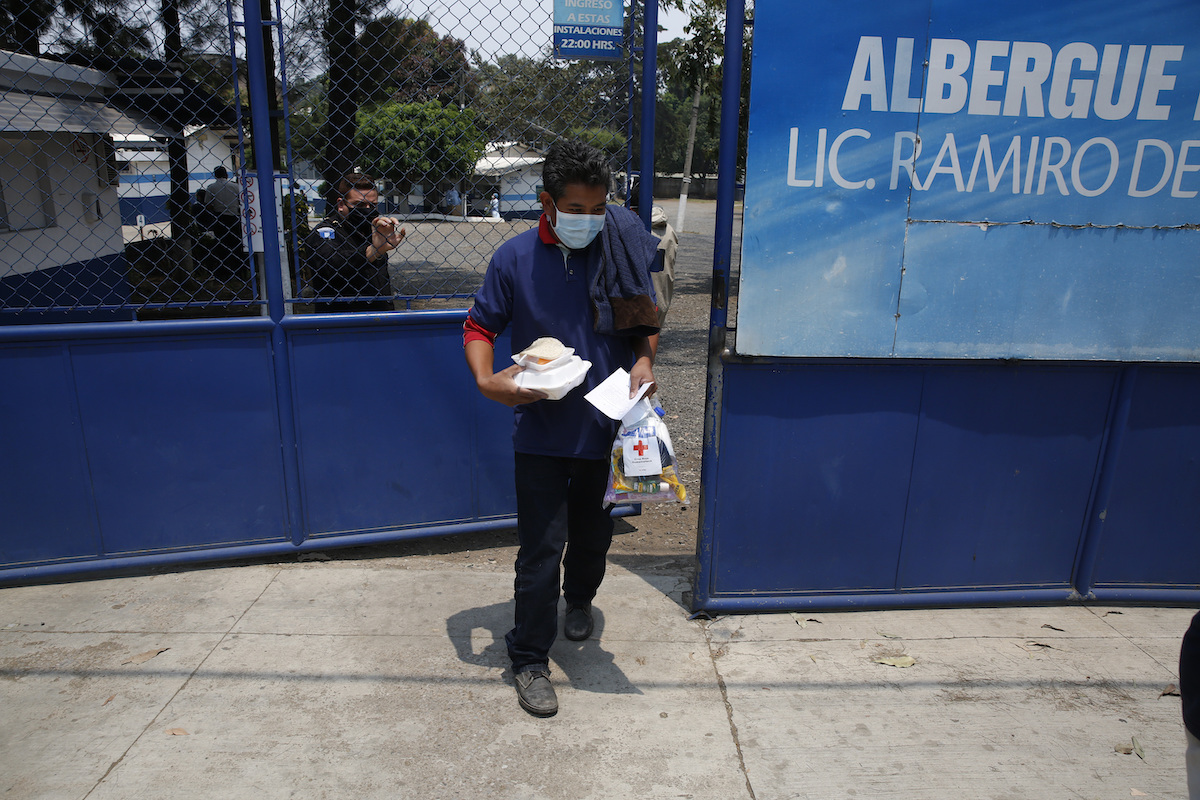

A deported man leaves the site where Guatemalans returned from the U.S. are being held in Guatemala City, Friday, April 17, 2020. (AP Photo/Moisés Castillo)

Giammattei, who spoke while wearing a surgical mask, said a team from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also tested 12 of the passengers at random on Friday and all tested positive. He said flights would be suspended until the U.S. certifies passengers on such flights are free of the new virus.

“It’s very worrying because these adults and children are being deported from places with high levels of contagion,” said Leonel Dubón, director of Refuge for Childhood, a center for young and vulnerable deportees in Guatemala.

ICE has restricted the movement of hundreds of detainees across the United States after they were suspected of coming into contact with an infected person, according to interviews with detainees and lawyers. The agency says 124 have tested positive for COVID-19 in 25 detention facilities.

A Department of Homeland Security official who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss internal procedures said not everyone in immigration custody is tested because there are a limited number of tests available not just to ICE but worldwide.

“We are only testing individuals we have reasons to believe may have the disease because of symptoms or close contact with individuals with symptoms,” the official said.

DHS learned that four on a March 26 flight tested positive after arriving in Guatemala. Last week it started ensuring that everyone on deportation flights has a mask, and on Thursday began pulling people off if they had a temperature of 99 degrees, instead of 100.6 previously.

The U.S. will consider new procedures if needed but has no plans to halt removals, the official said: “We continue to feel strongly that each country has an obligation to receive its citizens, that taking those individuals out of custody is the safest situation for them.”

At the Richwood Correctional Center in Monroe, Louisiana, three cases had been confirmed and dozens of detainees are under lockdown. One Guatemalan detainee who has COVID-19, Diego Ortiz García, said Friday he is confined to a dorm with about 20 others suspected of having the virus. ICE said late Friday that it had confirmed 20 COVID-19 cases at Richwood.

Another Richwood detainee who was infected, Salomón Diego Alonzo, was hospitalized Thursday. According to his attorney, Veronica Semino, Alonzo was taken there shortly after a guard told an immigration judge he “does not have the lung capacity” to speak during a hearing he listened to remotely, by phone.

So far there hasn’t been any documented case of the virus among deportees to other countries in Central America’s Northern Triangle region.

In El Salvador, more than 800 have arrived over the last month and been placed into 30-day quarantine. President Nayib Bukele said in a statement to AP that 70 percent have been tested with none coming back positive. Tests are pending for the rest.

Honduran officials said they weren’t aware of any cases among deportees, who undergo 14-day quarantine on arrival even if asymptomatic.

That hasn’t eased concerns.

“Every airplane that arrives with deportees is an alarm bell for the communities in our countries” said César Ríos, director of the non-governmental Salvadoran Institute of Migration.

A deported woman looks at her family as she picks up the food they brought her, at the site where Guatemalans returned from the U.S. are being held in Guatemala City, Friday, April 17, 2020. (AP Photo/Moisés Castillo)

ICE has said 25 employees at U.S. detention centers have tested positive including 13 at a removal staging facility in Alexandria, which has sent at least 17 flights to Guatemala this year. It has not said how many of the 32,000 people in U.S. immigration detention have been tested.

Attorneys for detainees have raised concerns about the risks of holding people in close proximity. About half of those in ICE detention have no criminal history apart from an immigration violation, and advocates question whether they need to be in custody given the crisis.

Despite twice halting deportation flights briefly, Guatemala has been receiving about one per day carrying 50 to 100 people from a variety of U.S. locations over the last month, a sharp reduction from the normal pace.

Dr. Michele Heisler, a professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan, said ICE’s practice of screening only deportees with fevers is “absolutely inadequate” and it would be best to test them all.

With a population of 17.2 million, Guatemala had 235 confirmed cases as of Friday afternoon.

“Guatemala will be overwhelmed,” Heisler said. “They already have a very fragile health care system. From a public health and medical perspective, this is just unbelievably irresponsible of our country.”

***

Merchant reported from Houston, Fox from Washington and Weissenstein from Havana. Elliot Spagat in San Diego, Colleen Long in Washington, Marcos Alemán in San Salvador and Marlon González in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, contributed.