Pensioners queue outside a bank during the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak in Buenos Aires on April 3, 2020. Photo by JUAN MABROMATA/AFP via Getty Images)

By Vincent Guermond, Royal Holloway and Kavita Datta, Queen Mary University of London

As the coronavirus pandemic hits jobs and wages in many sectors of the global economy that depend on migrants, a slowdown in the amount of money these workers send back home to their families looks increasingly likely. These international remittances will be crucial in transmitting the unfolding economic crisis in richer countries to poorer countries. They will fundamentally shape how, and the pace at which, the world recovers from coronavirus.

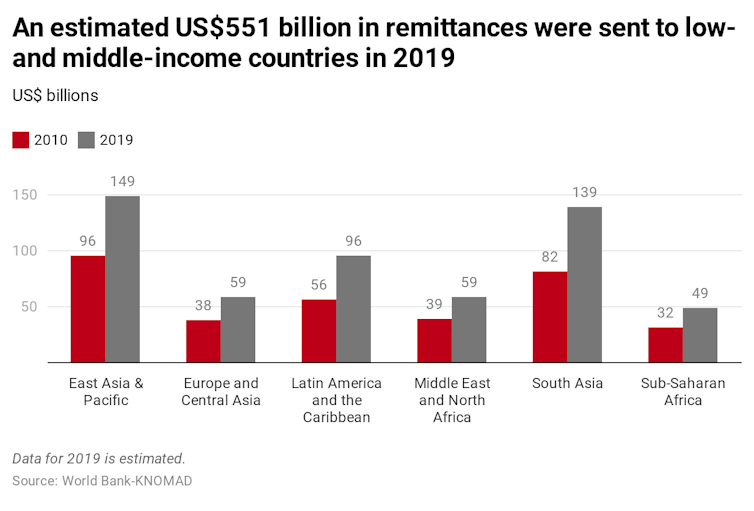

Remittances shelter a large number of poor and vulnerable households, underpinning the survival strategies of over 1 billion people. In 2019, an estimated 200 million people in the global migrant workforce sent home US$715 billion (£571 billion). Of this, it’s estimated US$551 billion supported up to 800 million households living in low- and middle-income countries.

The majority of remittances are small sums of money, spent by recipients on everyday subsistence needs including food, education and health. The World Bank projects that within five years, remittances will outstrip overseas aid and foreign direct investment combined, reflecting the extent to which global financial flows have been reshaped by migration.

But the social distancing and lockdown measures used to contain the spread of coronavirus have led to a global economic slump, with the International Monetary Fund predicting the global economy will contract by 3% in 2020. Three issues make this looming crisis particularly salient for the migrant workers who generate remittances.

Migrant Workers at Risk

First, as the Institute for Public Policy Research think tank illustrated in a recent briefing, migrant workers tend to work in sectors that are particularly vulnerable at times of an economic downturn and have less employee protections. They are also more likely to be self-employed.

Second, the access migrant workers have to public funds is —with some exceptions— specifically restricted as a condition of their visas. So it’s uncertain whether they will be able to access the already limited government interventions to mitigate the effects of the pandemic. For example, the South African government’s initiative to help small- and medium-sized businesses is only available for those with South African citizenship.

Third, and as a result of this, migrant workers adopt a series of strategies or tactics to cope. They often continue to work in compromised circumstances, such as in jobs with lower wages, poor working conditions and, in the current crisis, exposure to infection. They also restrict their spending – and contemplate a return back home.

In the UK, some migrants are hyper-visible NHS doctors and nurses. Their labour has been somewhat belatedly acknowledged by the government, and their importance to the health service demonstrated by the Home Office’s decision to extend all visas of health workers coming up for renewal by a year.

But many more migrants are hidden and largely unsung heroes who continue to work in so-called semi-skilled or unskilled jobs in sectors such as food manufacturing and delivery, social care and cleaning. High rates of infection among Somali migrants in Norway, for example, are partly attributable to their concentration in these “close-contact” professions where home working is not an option.

The 2008 Financial Crisis

The 2008 financial crash and recession provide some indications of how this crisis in migrant work may affect remittance flows. Between 2008 and 2009, remittance flows declined by 5.5% globally. Some parts of the world saw even more marked declines. Transfers to Latin America and the Caribbean, most originating from the US, decreased by 12%. Migrants remitted smaller amounts, more infrequently, or in extreme cases, stopped altogether as they were laid off and faced uncertain future employment prospects.

Early predictions of the impact of coronavirus on remittances detail significant declines. One study by the Inter-American Dialogue estimated there would be a 7% decline in remittances from the US, which will fall from by US$76 billion to US$70 billion, with receiving households from Mexico and Central America being most affected. According to another study by BBVA Research, remittances to Mexico could fall by 17%.

With the global economy slowing down even before coronavirus, and the pandemic affecting different parts of the world over different timelines, long-term recovery prospects are unclear. The particular vulnerability of poor countries is apparent with the World Bank pledging US$160 billion over the next 15 months to aid both immediate health priorities and longer term economic recovery.

It remains unclear whether that US$160 billion is adequate and will reach vulnerable households, particularly given the negative impact the World Bank and IMF’s historic structural adjustment programmes, in which strict spending conditions were attached to aid, had on the healthcare systems of many developing countries.

In contrast, remittances —often known as aid that reaches its destination— constitute a significant safety net for vulnerable households. Our own research shows that remittances don’t just reach immediate household members but are also distributed among extended family and friends. They also support local economies through family payments to shopkeepers and construction workers. In regions such as the Horn of Africa, where 40% of households are heavily dependent upon remittances, any disruption in flows sent by the Somali diaspora will further exacerbate food insecurity.

How richer nations respond to the current crisis will have significant economic ramifications for countries dependent on remittances. Richer nations must adopt inclusive economic policies which both protect the livelihoods of migrants and reduce the socio-economic impacts of the pandemic. Their jobs are linked to the survival of millions of others.![]()

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.