In this April 13, 2020 photo, signs on the boarded up 11th Street Diner pay tribute to front line workers during the new coronavirus pandemic in Miami Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky, File)

By Gabriel R. Sanchez, Melanie Sayuri Dominguez and Edward D. Vargas

A shorter version of this analysis was published previously at Latino Decisions.

As more data becomes available across states and cities across the country, it has become more and more apparent that the coronavirus is hitting racial and ethnic communities at a much higher rate than white Americans. For example, data from Louisiana’s Department of Health showed Blacks account for 70 percent of coronavirus deaths in the state, despite making up just 32 percent of the population. In New York City, according to recent data analysis, the death rate for Latinos in the city is approximately 22 people per 100,000; the rate for African Americans is 20 per 100,000, both of which are double that of whites (10 per 100,000). Strikingly, while Latinos make up 29 percent of the NYC population, they represent 34 percent of the people who have died of the coronavirus. This is followed by Blacks who make up 22 percent of the population, but represent 28 percent of corona deaths.

Leading public health experts, including Dr. Camara Jones, have shed light on this important issue and properly identified that the underlying causes for the racial and ethnic differences in positive tests and deaths associated with the coronavirus are due to inequalities in social determinants of health. We agree with this perspective and want to add to the discussion with some new data based on our national on-line survey (n=4,000). The survey allows for the examination of any behavior changes across the public, with a particular focus on how changes in daily activities to stop the spread of the virus may have varied based on race. The survey was fielded between March 12 and 15, dates that overlapped President Trump’s announcement of a national emergency in response to the coronavirus outbreak on March 13.

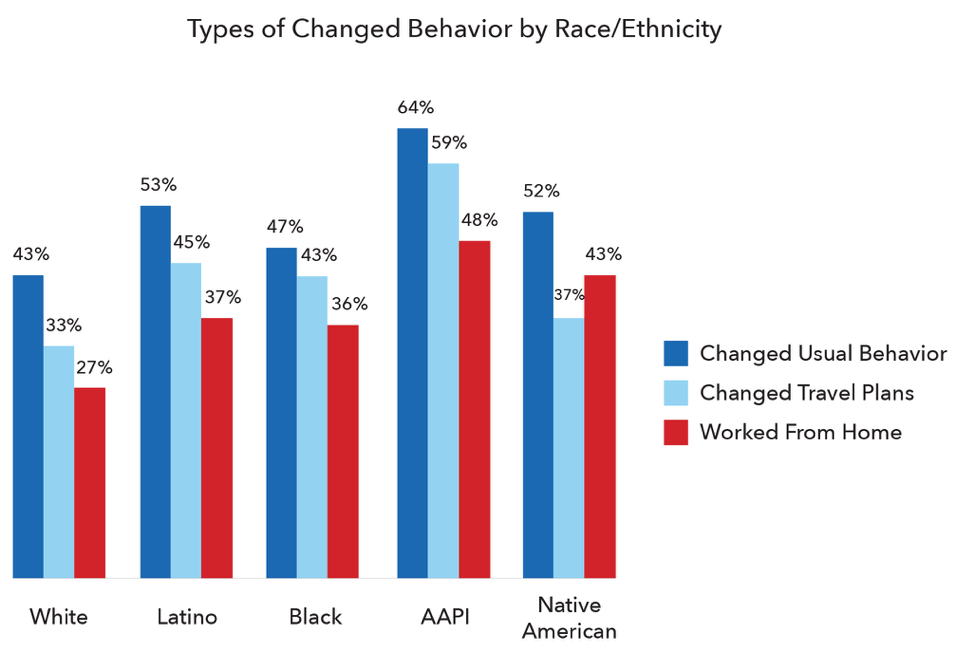

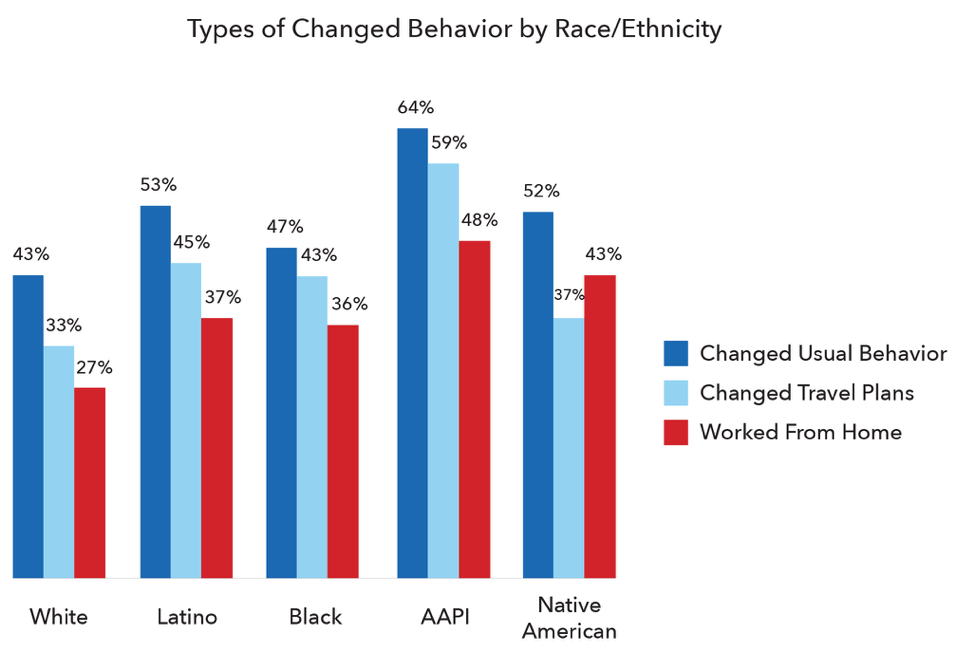

The growing concern about the potential spread of the virus has led many Americans to change their travel plans, work remotely from their home, and take other steps to reduce interactions with others. The survey asked respondents to report whether they had done any of the following in order to attempt to reduce the spread of the virus: changed travel plans, work from home instead of going to your usual place of work, or changed any other usual behaviors. The survey was conducted at a time when the severity of the virus to the United States population was becoming clear but before many states began issuing closures to non-essential business, which presented a great opportunity to explore voluntary changes in behavior.

As reflected in the figure below, racial and ethnic minorities were more likely than whites to have shifted their behavior across all three measures. For example, the Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) community was nearly twice as likely to report that they made travel plans to help reduce the spread of the virus (59% compared to 33%), with Latino and African respondents also being more likely than whites to have followed this important suggestion from public health leaders at the time. The difference between each of these racial groups is statistically significant, and although not significant, Native Americans were also more likely to have revised their travel plans.

Multi-wave National Panel Study of COVID19 (n=4000)

There is a similar pattern for reported changes to other usual behaviors. While 43% of non-Hispanic white respondents reported that they have changed usual behaviors as a result of the coronavirus, Latinos and Native Americans were approximately ten percent more likely to shift behavior, African Americans 14% more likely, and AAPI a robust 21% more likely than whites to change behavior. The gap in reported change in travel plans is statistically significant for all groups.

Finally, the survey asked respondents whether they have moved from their usual places of work to working from home to help reduce the possible spread of the virus. Once again racial and ethnic minorities were more likely to report shifts in behavior, with statistically significant differences between all four groups and whites. The difference between members of the AAPI community and whites was again the widest at 21%, with at least ten percent gaps for Latinos (+10%) and Native Americans as well (+16%). The difference between whites and African Americans was 9%. It is important to note the observed differences in working from home we found in our survey are significant despite underlying racial inequalities that have been noted in the ability to work from home across the workforce.

If the racial and ethnic differences that have been reported by several jurisdictions highlighted in our opening are not due to behavior, then they must be due to inequalities in social conditions that put these communities in higher risk. This includes racial and ethnic minorities living in higher population density and racially segregated neighborhoods where the virus can spread more quickly, having higher rates of asthma due to living in poor air quality areas that makes the impact of the virus much stronger, and a host of other “underlying health conditions” that racial and ethnic minorities suffer from due to vast inequalities in poverty rates and access to health insurance and health care.

Our research team will continue to track potential differences in behavior by race and ethnicity as well as how the in-direct consequences of the coronavirus including job loss, loss of employment-based health insurance, and stress and anxiety due to these issues may lead to even more severe racial and ethnic health inequalities than before this health epidemic started.

***

Gabriel R. Sanchez is a Professor of Political Science at the University of New Mexico. He is the Executive Director of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Center for Health Policy and Co-Director of the Institute of Policy, Evaluation and Applied Research (IPEAR) at the University of New Mexico.

Melanie Sayuri Dominguez is a Doctoral Candidate in Political Science at the University of New Mexico and a Doctoral Fellow for the University of New Mexico’s Center for Social Policy.

Edward D. Vargas is an Assistant Professor of Transborder Studies at Arizona State University.