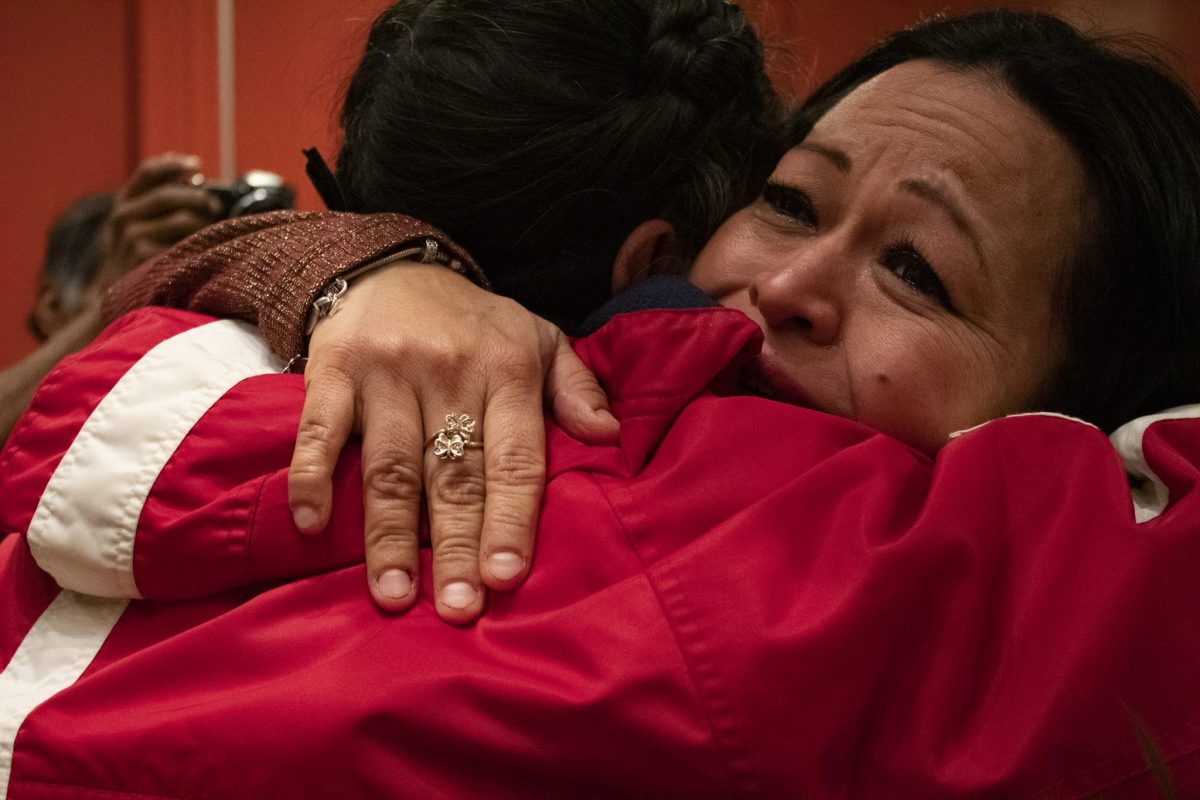

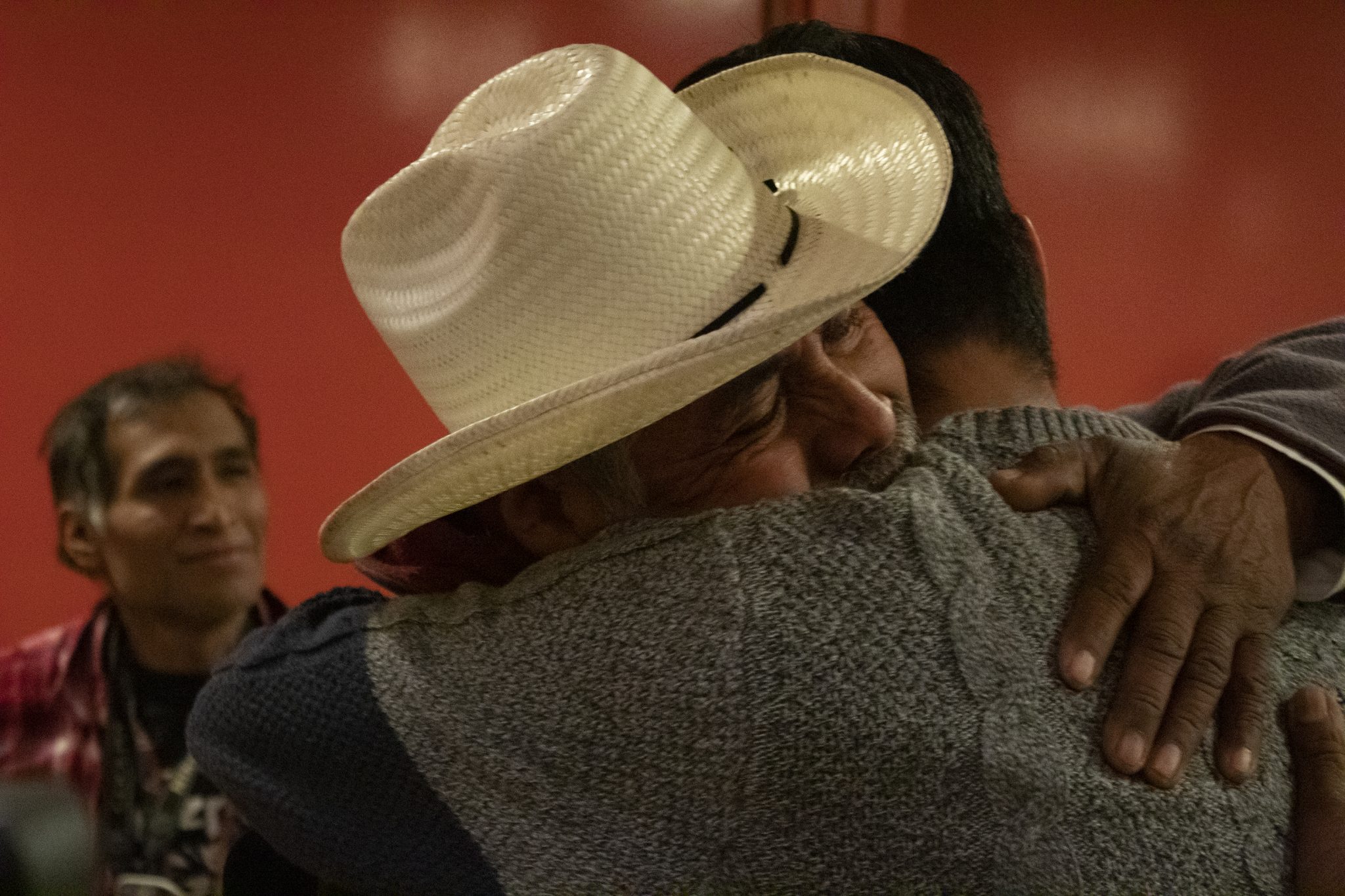

(Photo by Mariana Calvo/Latino Rebels)

It has been about two months since New York City locked down to prevent the spread of COVID-19. For weeks, we have heard harrowing stories of people dying alone in hospital rooms, of businesses shuttering, of canceled milestones, of lives irrevocably changed, and far too many, shattered. Coronavirus has brought our city to its knees, but its impact has not been equal.

Data from the New York City government shows that POC communities have been the hardest hit by the coronavirus because of unequal access to economic opportunity or healthcare. Many are essential workers and don’t have the luxury to work remotely or to not work at all.

Among Latino New Yorkers, one group has been especially impacted —undocumented immigrants— as they are not eligible for any of the benefits outlined in Congress’ stimulus bill. When I consider the situation that most of us living in a lockdown are in, particularly when it comes to facing the difficulty of being away from loved ones, the undocumented community is one that has faced family separation and distancing time and time again.

As a photographer of Mexican origin based in New York City, I have paid close attention to the images of Latino New Yorkers who have succumbed to COVID-19.

I think about the immeasurable pain their families are going through, both in the United States and abroad. I think about how that pain is especially acute for undocumented immigrants who had waited for decades to reunite with the family members they left behind who will no longer get the chance to see them again. I think about a family reunification event I witnessed just weeks before the coronavirus began its spread around the world.

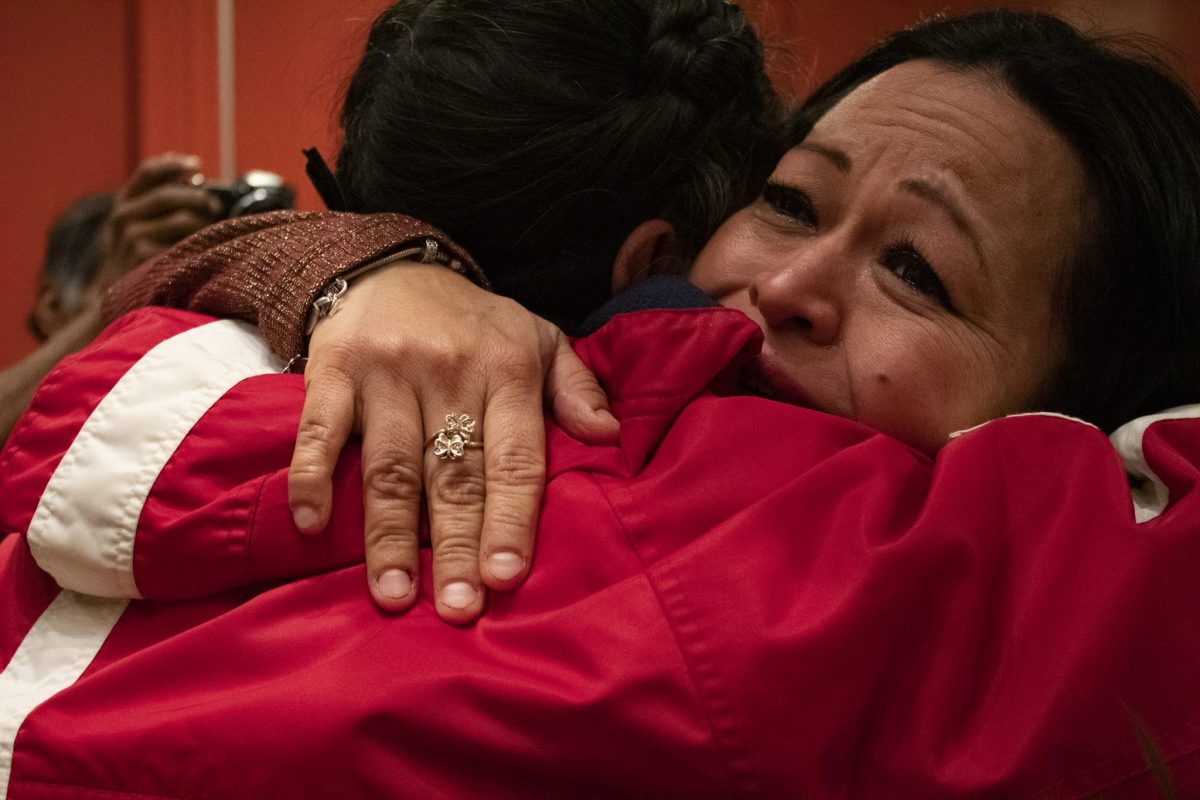

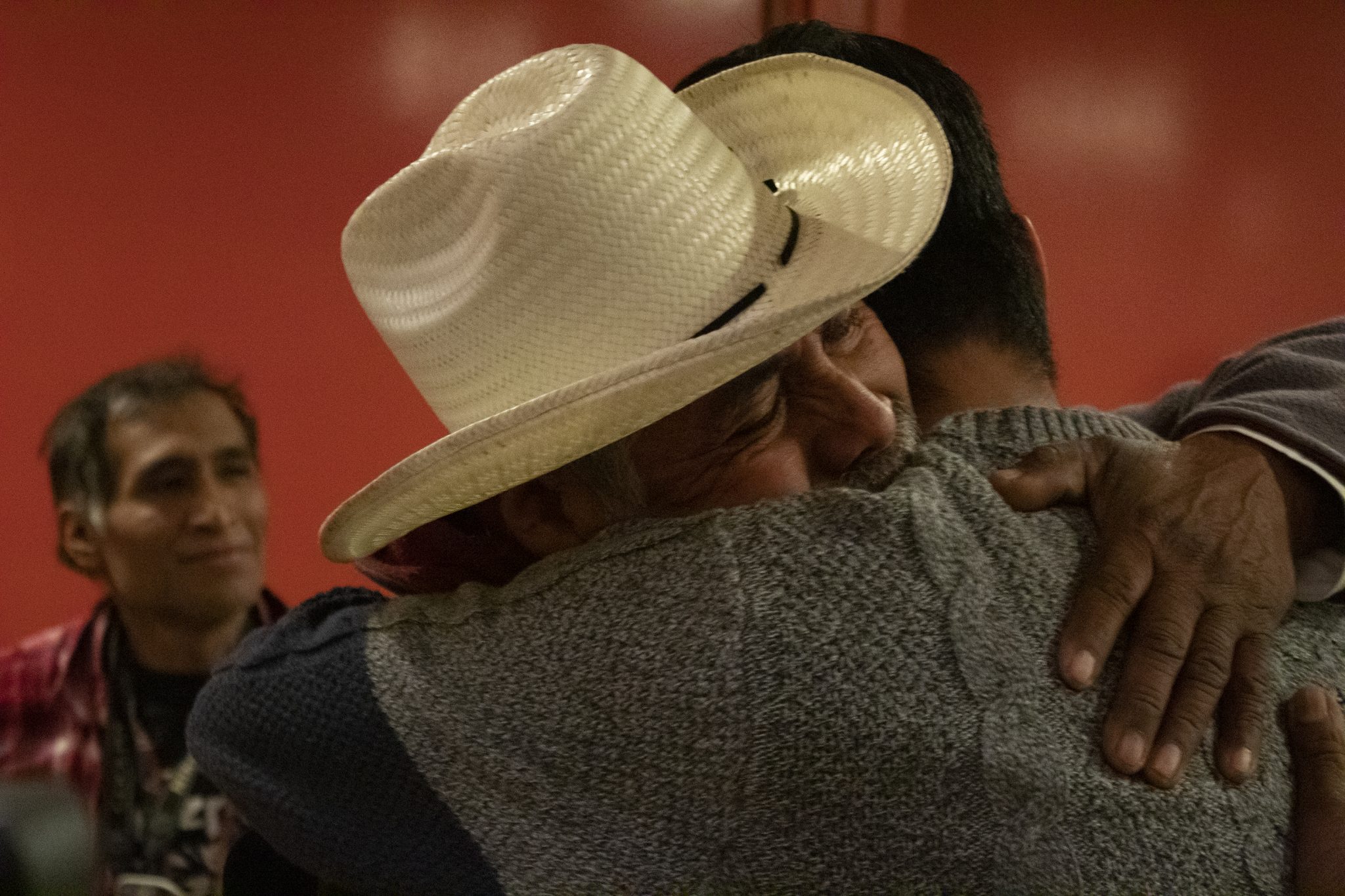

(Photo by Mariana Calvo/Latino Rebels)

At times, I now wonder if events like it will ever happen again.

For the past several years, Mexican states had been cooperating with the U.S. Department of State to create three-week visiting programs where elderly residents were allowed to reunite with their U.S.-based relatives and meet spouses and grandchildren they had only interacted with through phone calls and WhatsApp messages.

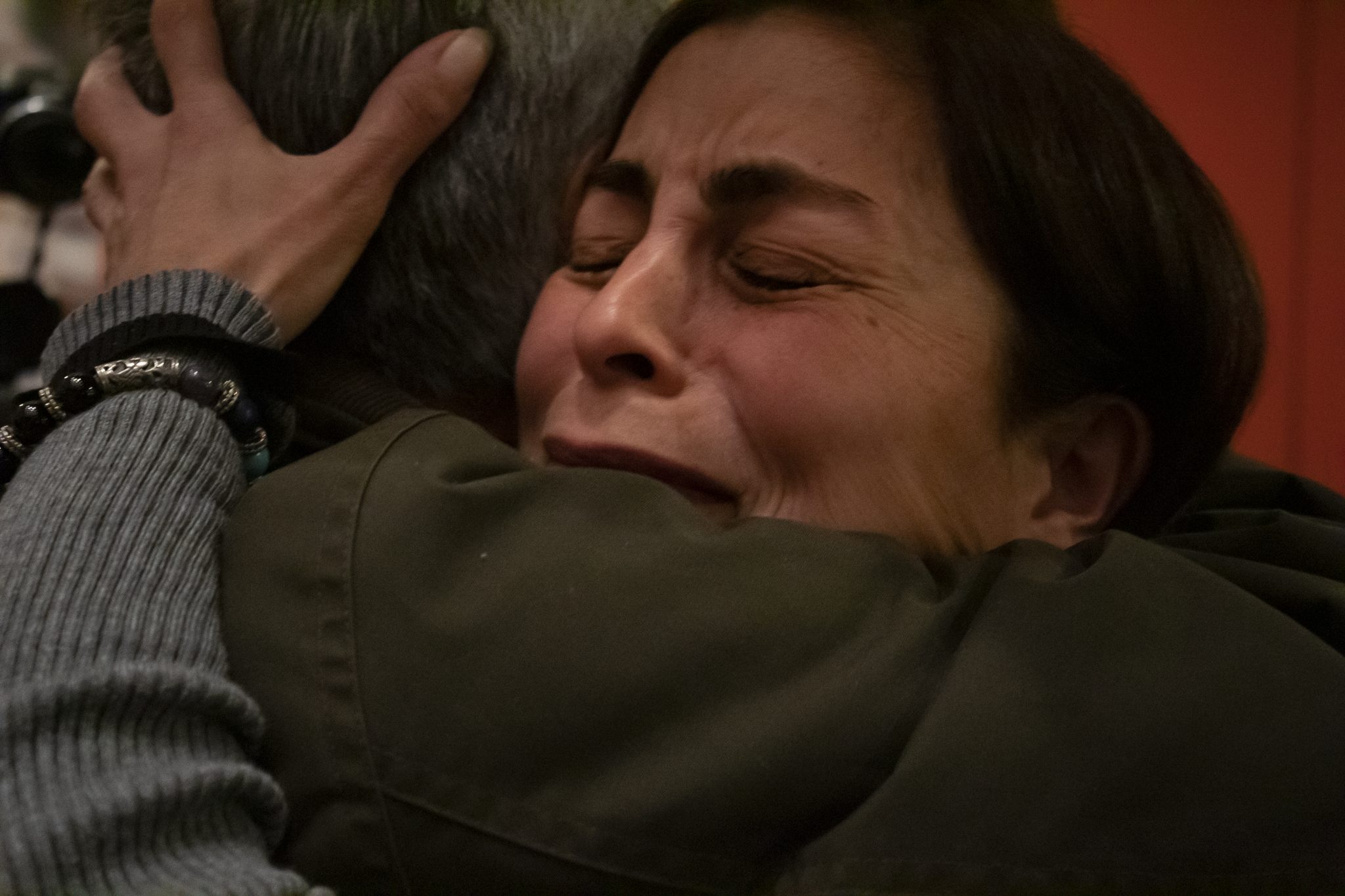

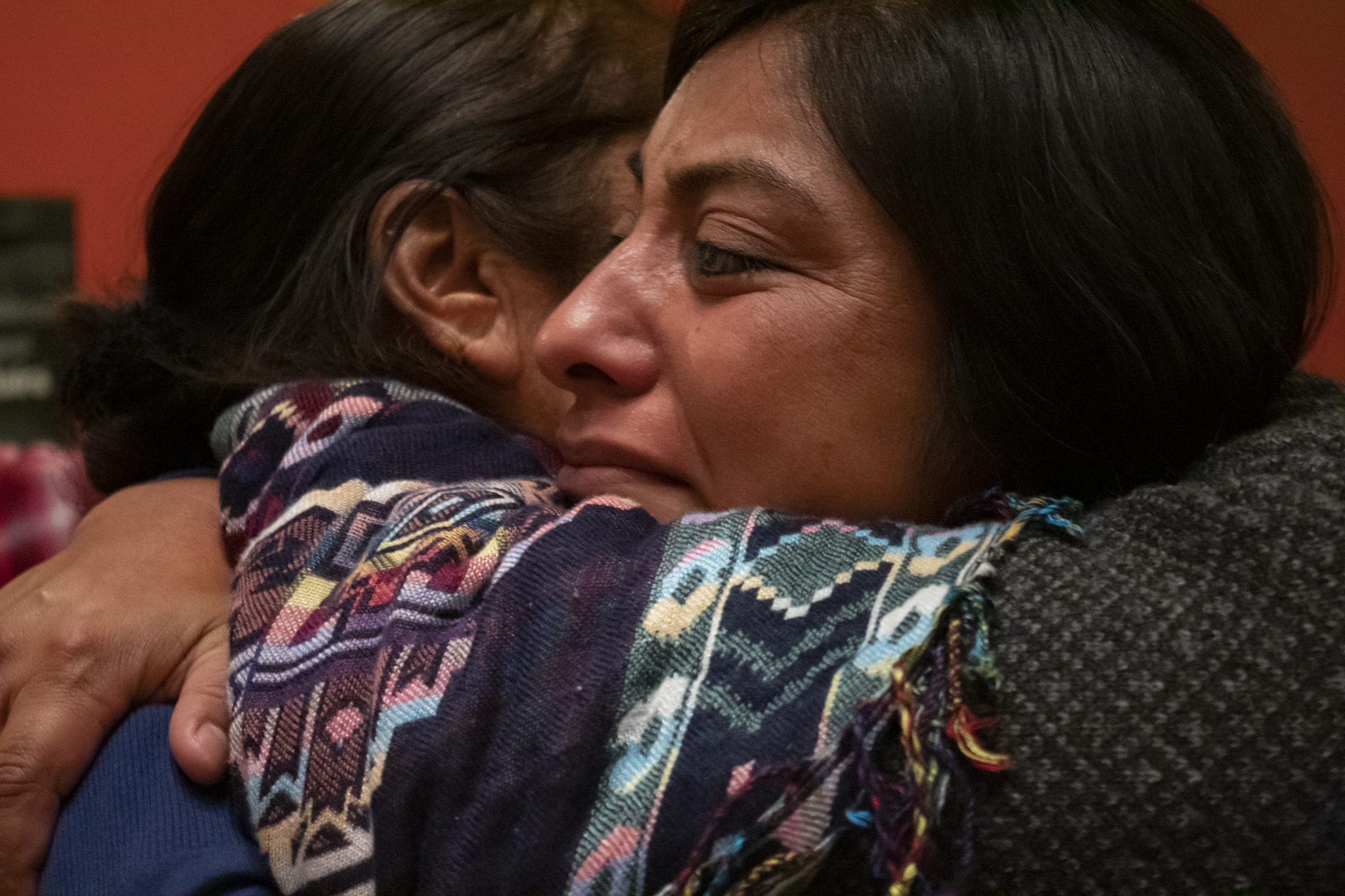

(Photo by Mariana Calvo/Latino Rebels)

Prior to COVID-19, Mexican families separated by U.S. immigration laws had been reuniting in cafeterias, schools, and churches across the country in events held by their home states to promote these visiting programs. They were rare but necessary opportunities for some of the five million undocumented Mexicans in the United States who have elderly parents and grandparents they are unable to see.

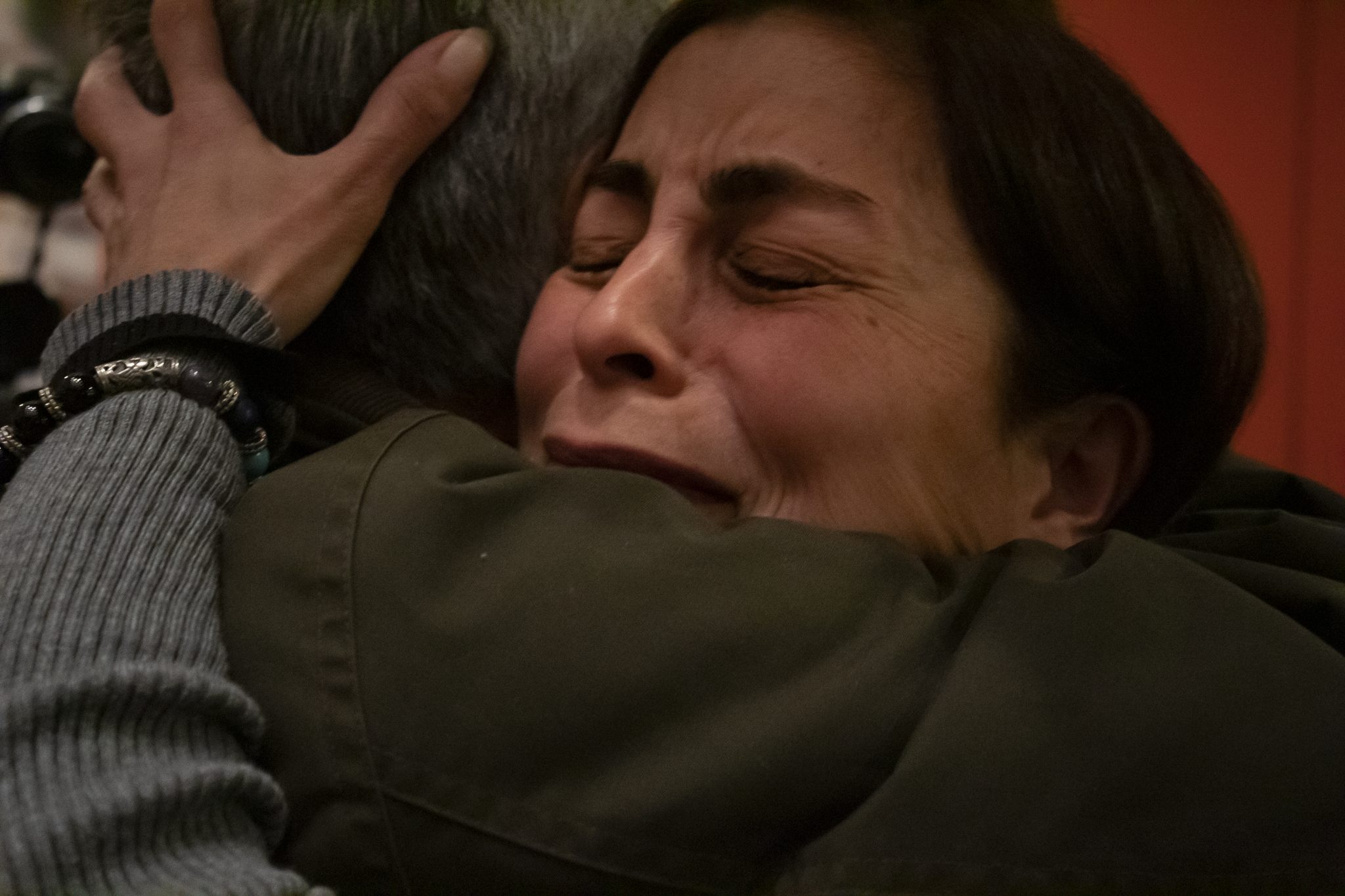

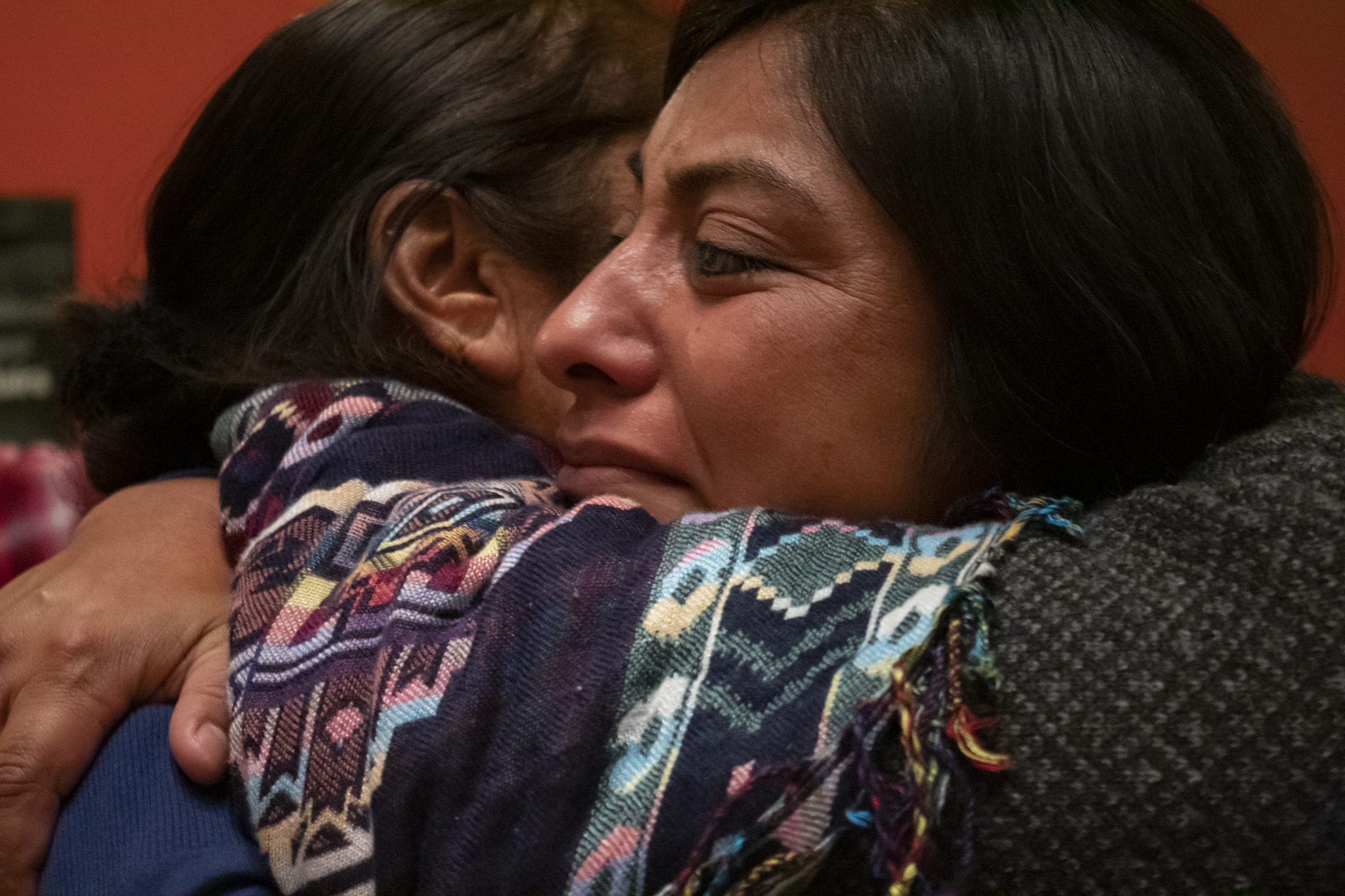

(Photo by Mariana Calvo/Latino Rebels)

In December of 2019, I was invited to photograph one of these powerful events at a church basement in midtown Manhattan. It was called the Guelaguetza Familiar and it was hosted by the Mexican state of Oaxaca, the second-largest home state of Mexican immigrants in the tri-state area.

Over the course of two hours, I witnessed the emotional reunification of 43 families who had been separated for decades. There were laughs. There were tears. There was hope. It was a quiet yet urgent rebuke of the age of “family separation” and a testament to the incredible sacrifices that come with the pursuit of a better life. And now, because of COVID-19, events like the the Guelaguetza Familiar have been postponed indefinitely.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo/Latino Rebels)

At the time, attending the Guelaguetza Familiar felt like a privilege and now in the age of social distance even more so.

While we still do not fully understand the true character of the coronavirus and the COVID-19 disease, the one thing we know with certainty is that staying away from our loved ones —especially our elderly loved ones— is the one way to keep them from contracting the virus and dying before their time. Perhaps, it is also a lesson in empathy.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo/Latino Rebels)

For decades, immigration laws have forced undocumented immigrants to socially distance from their loved ones, a kind of pain that those of us who once lived with unrestricted movement are only beginning to understand. We are learning a lesson that undocumented immigrants have long known: that sometimes to protect those we love, we have to stay away from them. But it doesn’t make it any less difficult.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo/Latino Rebels)

During this pandemic, it is undocumented immigrants who have been among the hardest hit. Adding to their vulnerability, undocumented immigrants are also far less likely to seek medical attention and many have died at home as a result. They have died thousands of miles away from their families who they work tirelessly to support.

Dead, because they were trying to keep their hometowns alive.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo/Latino Rebels)

Millions of us are anxiously awaiting the end of social distancing. But with no end in sight, we ache to embrace our loved ones and to resume what once felt like a certain kind of freedom. We cling to memory and we forget that for some of the most vulnerable members of our society embracing their loved ones and feeling free has been for far too long, an elusive, but resilient dream.

And yet they still dream, and we can dream too.

We must.

(Photo by Mariana Calvo/Latino Rebels)

I share the above selection of photographs that I took of families embracing at one of the last family reunification events hosted by the Mexican government for the foreseeable future not as a relic of the past, but as a glimpse into the future. It is my hope that these images foreshadow a future in which family reunification is not a casualty of the coronavirus, but rather a reckoning with what we owe those willing to die for their families and for us too.

***

Mariana Calvo is a freelance photographer and writer originally from Mexico City. She has worked in Guatemala, Colombia, and the United States. She is currently a Lewis Hine Fellow covering the role of barriers to employment on low-income New Yorkers.F ollow her on Instagram and Twitter.