Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador waves a starting flag during a ceremony in Lázaro C´årdenas, Quintana Roo state, Mexico, Monday, June 1, 2020. (AP Photo/Víctor Ruiz)

By MARK STEVENSON, Associated Press

When Andrés Manuel López Obrador won Mexico’s presidency after years of agitating for change, many expected a transformative leader who would take the country to the left even as much of Latin America moved right.

Instead, López Obrador is leading like a conservative in many ways—cutting spending, investing heavily in fossil fuel development and helping the U.S. crack down on the northbound flow of migrants.

As coronavirus spreads through Mexico, the president known as AMLO has rejected widespread shutdowns and pressed to keep the economy going. He’s used the pandemic to justify weakening environmental protections, and pushed for oil-centered infrastructure projects despite the collapse in petroleum prices. He’s resisted both economic stimulus programs and expansion of coronavirus testing and tracking.

López Obrador is resuming his trademark tours of the Mexican countryside this week despite the fact that the country is suffering its highest rates of coronavirus infection and death rates so far.

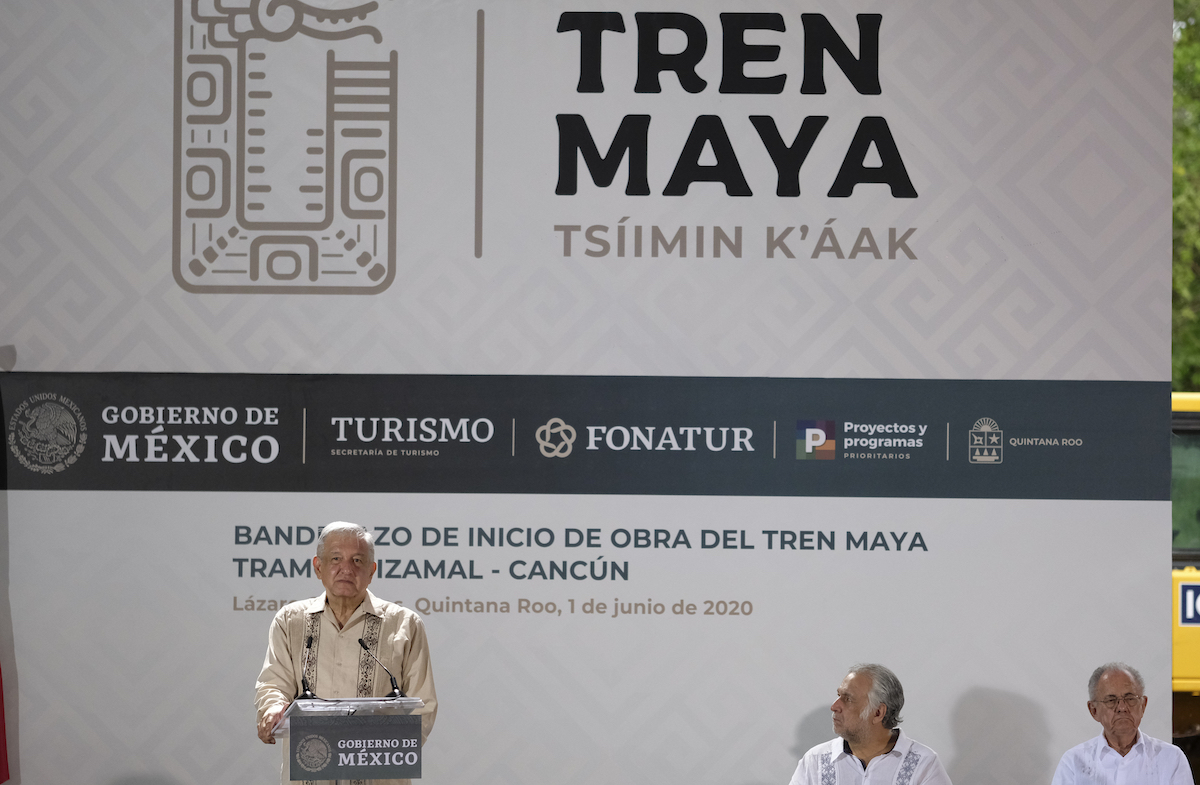

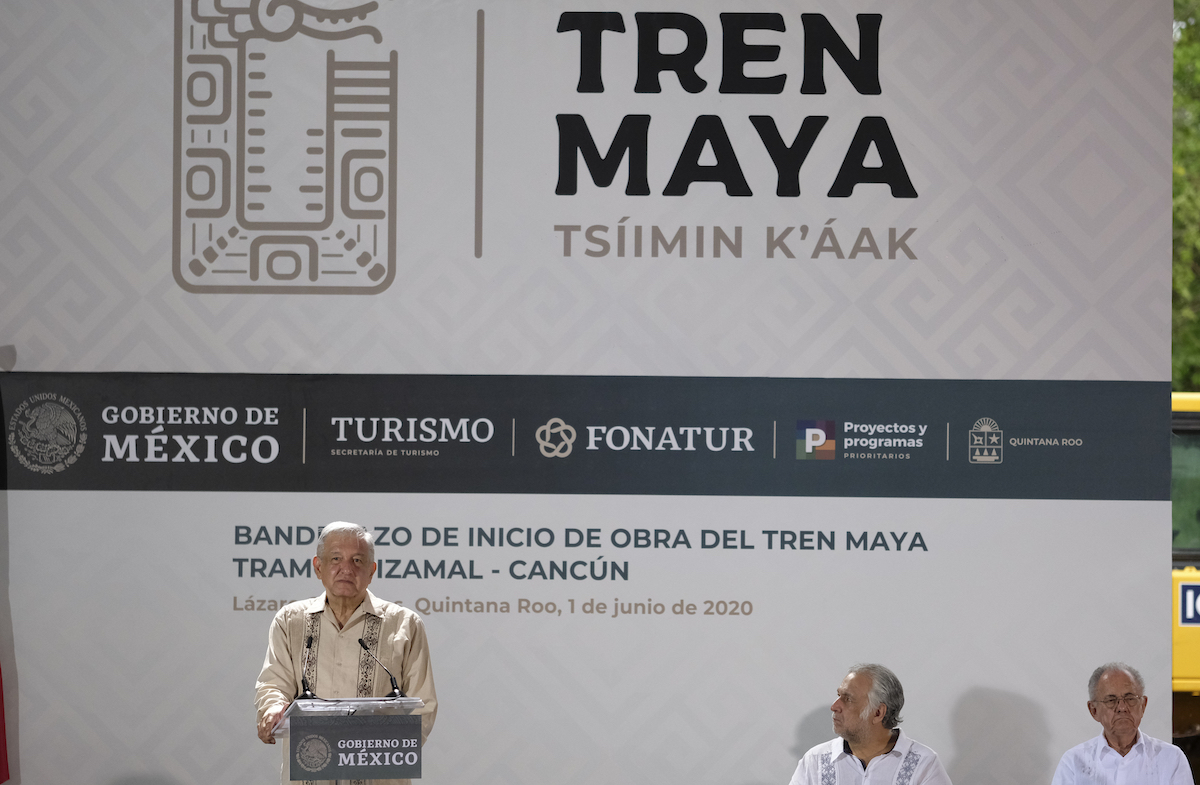

After a two-month hiatus, López Obrador this week kicked off construction of a tourist train that will link beach resorts and sites of ruins on the Yucatan Peninsula.

On Tuesday in the Yucatan capital of Mérida, López Obrador said Mexico’s economy would bottom out in April, May and June, but “from July forward we’re going to recover. The recovery is going to begin, that’s my forecast, I’m working for that.”

His only concession to the coronavirus pandemic is that he is no longer wading through crowds of supporters, kissing children and receiving hugs.

When he’s not on tour, López Obrador uses social media and daily press conferences to dominate the news cycle and label virtually any criticism as part of a conspiracy. Many observers draw parallels to U.S. President Donald Trump’s communication strategy.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador waves to supporters in Lázaro C´årdenas, Quintana Roo state, Mexico, Monday, June 1, 2020. (AP Photo/Víctor Ruiz)

“They really are similar,” said Federico Estévez, a political science professor at the Autonomous Technological Institute of Mexico.

When López Obrador doesn’t like what statistics show, he does not shy away from challenging them.

He recently suggested replacing gross domestic product, which hasn’t seen any growth in over a year, with a well-being index to measure happiness.

“We are going to ask people, not just about their material conditions, but about other factors like spiritual well-being, and not just material issues,” López Obrador said last week.

On coronavirus, Mexico says it is deliberately administering very few tests for the disease. Mexico has performed only about 250,000 tests for a nation of over 125 million, or less than 2 in 1,000 people, leading critics to say the country’s COVID-19 figures are greatly underestimated.

“The Mexican government, unlike many and perhaps most governments, has declared that its epidemiological policy has no intention of counting each and every case,” said Hugo López-Gatell, the assistant health secretary who is the president’s point-man on the virus. “We are not interested in it, because it is useless, costly and not feasible to test everybody in the country.”

AMLO was confronted with a choice of expensive, probably unobtainable testing, or a quick expansion of hospital beds and the choice for him was obvious: equip beds.

His single stated goal in the pandemic is “that we not be outstripped, that there be enough hospital beds.”

What’s more striking is the information Mexico hides: figures on “excess deaths,” or patterns of deaths from previous years that could serve to tell how many people have actually died this year compared to previous years of causes like pneumonia. There is a two-year lag in reporting such figures.

The civic group Mexicans Against Corruption said the strategy of little testing “limits the possibility of identifying super-spreaders, people who are asymptomatic and spread the virus massively,” and could spell disaster as the economy re-opens starting June 1.

On the economic front, López Obrador views the pandemic as an opportunity to deepen his drive toward a state-centered, nationalistic movement that is not beholden to international scrutiny.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, left, speaks during a ceremony in Lázaro C´årdenas, Quintana Roo state, Mexico, Monday, June 1, 2020. (AP Photo/Víctor Ruiz)

And like Trump, López Obrador has used the pandemic to weaken some environmental policies. If oil —the stuff that dreams were made of in his home state of Tabasco in the 1970s— is going out of fashion, why not just cancel the renewable energy projects that compete with oil? López Obrador is forging ahead with building a new oil refinery, even as excess capacity builds around the world.

His love of oil —he has canceled electricity purchases from new wind and solar energy projects, in part to save government-owned fuel-oil plants from competition— was born in his first government job in the 1970s. As head of indigenous affairs, he turned to the state-run oil company, Pemex, to help solve the lack of farmland in the swampy homeland of the Chontal Indians. He got Pemex to lend him a dredging barge and dredge up wetlands to pile soil into thin strips of land.

“The answer to understanding him is to go back and look at his hometown,” Estévez said, referring to the small Tabasco town where López Obrador grew up. “He’s never left that world. Biography does matter… In Tabasco it’s all public investment… that’s all he’s ever known.”

However, as the rest of the world turns Keynesian, expanding spending, Mexico’s president has gone to unprecedented lengths to cut budgets, asking public universities to give back part of their budgets, scientists to donate some of their pay, and federal officials to take a pay cut.

The president has granted no tax payment extensions, and instead relied largely on small loans to small and micro-businesses. He vows not to borrow a dime or even run up a budget deficit, a pretty inflexible stance given that Mexico faces a 10% drop in GDP and the loss of a million jobs this year. And he has angered private investors with moves like canceling the new solar and wind energy projects, many of which are already built.

According to report by Bank of America Global Research “the lack of testing will likely keep demand for services constrained even when supply restrictions are lifted, making for a weak recovery. The cleanest example is tourist-related services,” which are Mexico’s third-largest source of foreign revenues behind exports and remittances.

But while López Obrador’s stubbornness has paid off in some areas: he successfully played brinkmanship to win a fraction of the production cut that OPEC had been demanding. He got Walmart’s Mexico subsidiary to cough up $359 million in back taxes the government said it was due for the company’s 2014 sale of a restaurant chain. And López Obrador’s popularity hasn’t really suffered; according to a telephone poll of 500 people conducted for the newspaper El Universal in mid-May, López Obrador’s approval rating remained around 58%, essentially where it was in late 2019.

Still, López Obrador remains highly sensitive to criticism, labeling any call for reassessment of his policies as conspiracy against him, personally. He recently compared his critics to “buzzards,” accusing them of using coronavirus deaths in a bid to discredit him.

Civic groups say that information from death certificates —and anecdotal accounts of crematoriums running beyond capacity— suggest the death toll from COVID-19 may be three times as high as official figures.

“They started talking about deaths, later they claimed we were hiding deaths, and later they went with scenes of crematoriums, right up to three, four days ago, they were talking about the ovens being full at the crematoriums,” López Obrador said. “That is very perverse, very unethical.”