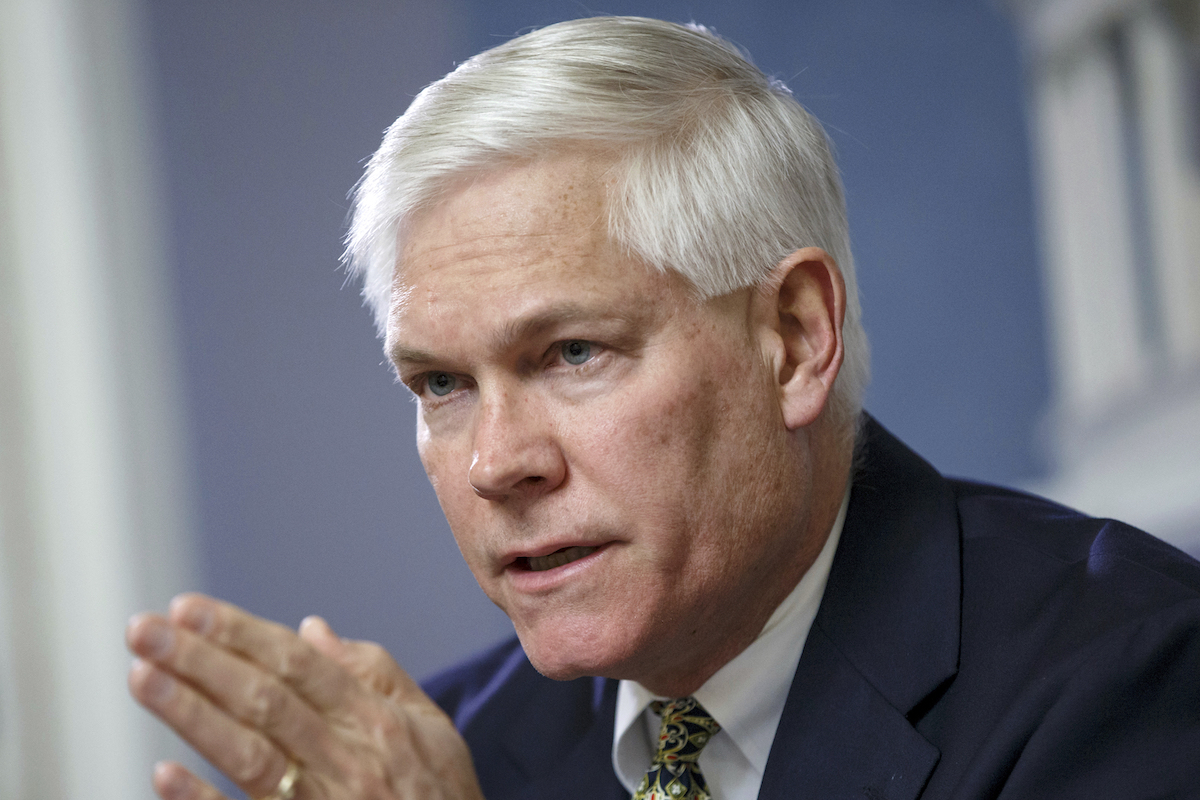

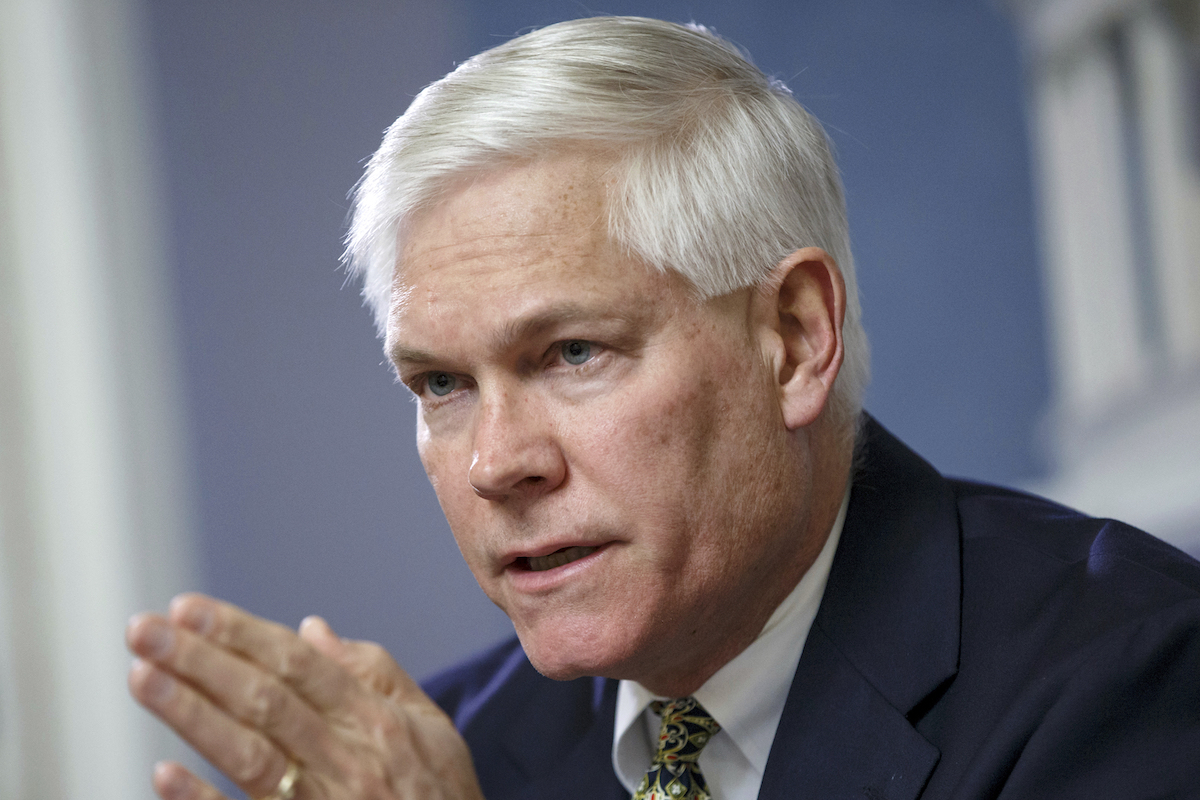

In this February 2, 2015 file photo, then Rep Pete Sessions, R-Texas, opens a meeting of the House Rules Committee at the Capitol in Washington. Venezuela’s socialist government tried to recruit former Congressman Pete Sessions to broker a meeting with the CEO of Exxon Mobil at the same time it was secretly paying a close former House colleague $50 million to keep U.S. sanctions at bay, The Associated Press has learned. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)

By JOSHUA GOODMAN, Associated Press Writer

MIAMI (AP) — Venezuela’s socialist government tried to recruit then-Congressman Pete Sessions to broker a meeting with the CEO of Exxon Mobil at the same time it was secretly paying a close former House colleague $50 million to keep U.S. sanctions at bay, The Associated Press has learned.

An official at state-run oil giant PDVSA sent an email to the Texas Republican on June 8, 2017 seeking his help arranging a meeting between Venezuela’s oil minister and Darren Woods, then Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s successor at the helm of the Irving, Texas-based Exxon. The purpose: to lure Exxon back to Venezuela after a decade’s absence and inject much-needed dynamism into the OPEC nation’s collapsing oil industry.

The email, which was seen by the AP, has been shared with U.S. federal law enforcement looking into the person who allegedly instructed the PDVSA official to send the email to Sessions: former Miami Congressman David Rivera, according to two people familiar with the investigation who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss the politically sensitive matter.

Rivera at the time was collecting part of a whopping $50 million contract for three months of consulting work for an American unit of PDVSA—a business deal now being investigated by federal prosecutors in Miami because he never registered as an agent of a foreign government.

It’s not clear how Sessions, who is running again for Congress this fall, acted on the request, though he did not reply directly to the email. In any case, Exxon rebuffed the sought-after meeting in Dallas, according to the two people.

But Sessions did engage in other mediation efforts in Venezuela over the next 15 months.

At the urging of a Venezuelan media mogul who would go on to become a top U.S. fugitive, he secretly traveled to Caracas in April 2018 for a meeting with President Nicolás Maduro. The businessman, Raul Gorrin, was present at the meeting and Rivera served as a translator, a third person familiar with the visit said, also on condition of anonymity.

A few months later Sessions phoned the socialist leader with Rudy Giuliani, the U.S. president’s personal lawyer, around the same time both men were involved in another shadow diplomatic effort to fire the U.S. ambassador to Ukraine. Both men’s interest in Venezuela and Sessions’ advocacy of a Trump-Maduro meeting came as a surprise to John Bolton, according to the former National Security Adviser’s new book on his time at the White House.

The AP first reported Sessions’ peacemaking trip to Caracas in 2018. The earlier email regarding Exxon and his connection to Rivera was not known at the time.

In this February 24, 2011 file photo then Rep. David Rivera, R-Fla., talks during a freedom for Cuba march in Miami. Venezuela’s socialist government tried to recruit former Congressman Pete Sessions to broker a meeting with the CEO of Exxon Mobil at the same time it was secretly paying a close former House colleague $50 million to keep U.S. sanctions at bay, The Associated Press has learned. (AP Photo/Alan Diaz)

Sessions’ role in the ultimately futile back channeling, more extensive than previously believed, is now part of prosecutors’ examination of Rivera’s paid consulting and how the money he received from Venezuela —at least $15 million of the promised $50 million— was spent, the two people said.

While there is no indication Sessions benefited from Rivera’s consulting contract, the two men’s efforts overlapped, with the same interlocutors, and at times seemed aligned.

A far cry from today’s “maximum pressure” campaign by the U.S. to remove Maduro, there was a brief window following Trump’s 2016 election when the socialist leader was desperately looking to court American investment and repair relations with Washington.

Trump’s perceived softness on Russia, Venezuela’s top ally, spurred Caracas to quickly mount an influence campaign that included funneling through Citgo, PDVSA’s Houston-based subsidiary, $500,000 to Trump’s inaugural committee—topping contributions by corporate giants Verizon, Pepsi and Wal-Mart.

Sessions was considered a key target of Venezuela’s charm offensive because of his close ties to Tillerson —both men have held leadership positions in the Boy Scouts of America— and ties to the U.S. oil industry. Exxon is among the firms headquartered in his former Dallas district.

The five-sentence message sent to Sessions’ personal email address, which starts with the word “eagle,” is short on specifics. But it makes reference to earlier correspondence, also seen by the AP, in which Exxon General Counsel and Vice President Randall Ebner mentioned a willingness to discuss new business after the settlement around the same time of a long-running arbitration stemming from Venezuela’s takeover of an Exxon-run oil field in 2007.

To woo the company back at a time when oil production was collapsing, Maduro was ready to offer Exxon a concession in the Hugo Chávez Oil Belt, which sits atop the world’s largest crude reserves, the two people said.

“We thank you for your commitment to making this meeting happen,” concludes the email to Sessions.

Exxon declined to comment.

But by the time the ink dried on a $259 million payment schedule signed between Exxon and PDVSA on July 31, 2017, relations between the two countries had become more hostile.

The Trump administration started rolling out the first round of sanctions in response to Maduro’s plans to rewrite the constitution and undermine the opposition-controlled congress.

In this March 12, 2020 file photo, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro gives a press conference at the Miraflores presidential palace in Caracas, Venezuela. (AP Photo/Matías Delacroix, File)

Sessions is looking to return to Congress if he can win a mid-July runoff in a heavily Republican district near his native Waco different from the seat he held for 11 terms until he was ousted in 2018.

He declined to comment in response to detailed questions. “The U.S. Department of State would be your best resource for any information regarding contacts made with Venezuela,” a spokesman said.

The State Department declined to comment.

But U.S. officials all along have been suspicious of Sessions’ activities in Venezuela. Sessions had no obvious links to the country besides writing a letter in 2004 to the country’s banking regulators in support of financier Allen Stanford, a former Sessions donor who in 2012 was convicted in Texas and sentenced to 110 years in prison for running a $7 billion-plus Ponzi scheme.

The State Department played no role in organizing the two-day private trip to Caracas, two U.S. officials said on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive matters. Sessions had asked U.S. diplomats not to accompany him to the presidential palace, the officials said, although U.S. Embassy staff did see the congressman afterward at a small reception held for him at the Caracas mansion of government-connected businessman Raul Gorrín.

In 2018, Sessions’ then-spokeswoman Caroline Booth told the AP that her boss had spent the past year working to “resolve issues” in Venezuela at the request of a friend she didn’t identify. She said Sessions paid for all of his travel.

Gorrín at the time was trying to broker a soft exit for Maduro while paying Ballard Partners —Trump’s former Florida lobbyist— to explore expansion opportunities in the U.S. for his TV network Globovision. Along the way, he traveled to Washington to discuss Venezuela’s future with U.S. lawmakers and managed to get his photo taken shaking hands with Vice President Mike Pence in Florida.

Gorrín together with now-Venezuelan Vice President Delcy Rodríguez, a PDVSA board member, organized Sessions’ visit to Caracas and steered the lobbying contract toward Rivera’s Interamerican Consulting firm, according to the two people familiar with the Maduro outreach. The goal of the contract was to improve PDVSA’s “long-term reputation” and “standing” among “targeted stakeholders” in the U.S., according to a copy seen by the AP.

Rivera wasn’t an obvious choice to lead the effort, having made a name for himself among anti-Maduro exiles in Florida mimicking the anti-communist politics of his friend and one-time roommate Florida Sen. Marco Rubio. The three-month, $50 million contract far exceeded the $70,000 per month Citgo had long paid two established lobbyists, Cornerstone Government Affairs and Vantage Knight, for regulatory work.

Rivera’s ties to the Maduro government and Gorrín have been the target of a criminal investigation for over a year, according to a U.S. law enforcement official on the condition of anonymity to discuss the ongoing probe.

He was also sued recently in New York federal court by Citgo’s new board appointed by Juan Guaidó, the head of Congress recognized by the U.S. as Venezuela’s rightful leader. The lawsuit alleges he failed to describe any work performed while under contract, preparing just two of seven promised progress reports. Rivera has said that some of the money he received was destined for Venezuela’s opposition, but so far has offered no evidence or explanation to back that claim.

In this February 5, 2020 file photo, President Donald Trump welcomes Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaidó to the White House. (AP Photo/ Evan Vucci, File)

Meanwhile, Gorrín’s efforts came to nothing: a few months after introducing Sessions to Maduro, he was indicted in Miami on federal money-laundering charges, including allegations that he helped embezzle $200 million from PDVSA on behalf of the president’s stepsons.

Gorrín and Rivera did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

Sessions and Rivera have a history of working together.

As chairman of the National Republican Congressional Committee, Sessions helped elect Rivera to Congress in 2010 despite domestic abuse allegations that almost derailed his campaign. In 2012, he hosted a Washington fundraising reception for the freshman congressman.

Later, Rivera’s political career unraveled amid several election-related controversies, including orchestrating the stealth funding of an unknown Democratic candidate to take on his main rival in a South Florida congressional race and a state investigation into whether he hid a $1 million contract with a gambling company. He has never been charged with a crime.

Sessions, the son of recently deceased former FBI Director William Sessions, has had his brushes with scandal as well. Last year, he was entangled in the impeachment investigation centered on Trump’s dealings with Ukraine for writing a letter to Secretary of State Mike Pompeo seeking Ambassador Marie Yovanovitch’s dismissal after meeting with two associates of Giuliani with ties to the former Soviet republic.

***

Follow AP reporter Joshua Goodman on Twitter: @APjoshgoodman. Contact AP’s global investigative team at Investigative@ap.org.