On the left, Mike Ruiz Rivera, a native of Ponce and a resident of Newark, New Jersey, is a 42-year-old man who survived COVID-19 after more than half a month hospitalized. (Photo by Hiram Alejandro Durán | Center for Investigative Journalism)

Versión en español aquí.

por Vanessa Colón Almenas, Víctor Rodríguez Velázquez, Mc Nelly Torres and Coral Murphy

This investigation is possible in part with the support of the Pulitzer Center and the Facebook Journalism Project.

Miriam Moreno Santiago was picking up her mother’s luggage in Orlando, Florida, when she was told she wouldn’t be able to see her. They would be taking her directly from the airplane to the hospital because she was having trouble breathing. María Isabel Santiago Colón, her 68-year-old mother, lived in Brooklyn, New York, but health complications and her age drove her to move South with her daughter. However, her journey changed. Miriam was allowed to see her mom virtually every day. She was able to read biblical passages and put on her favorite church music. But, there was no parting hug. Santiago Colón died of complications from COVID-19 on April 21. Miriam was able to perform a virtual ceremony in honor of her mother.

María Isabel Santiago Colón with her daughter Miriam Moreno Santiago and her grandchildren. (Center for Investigative Journalism)

In New Jersey, Madelyne Osorio also lost her mother, Carmen María Osorio, 71. Although she had asthma, something else was wrong. She went to St. Michael’s Medical Center, but she was not tested for COVID-19, “because at that time not all hospitals had access to the tests.” Her daughter said that two hours later her mother was sent home. She lamented that they could not rule out that her mother had influenza, because they did not run that test either. Days passed and her health situation worsened.

“She was dehydrated,” Madelyne said in a slow tone and as if choosing the words that hurt the least to remember the event. On April 12 there was no going back. Carmen María was taken to another hospital, the Saint Barnabas Medical Center, she was left in the emergency room and her daughter never saw her up close again. Like Miriam, a video call served as a good-bye.

Madelyne Osorio’s mother died in April after going to a hospital where she was not tested for COVID-19 or Influenza and was discharged within a few hours. (Hiram Alejandro Durán | Center for Investigative Journalism)

William Sánchez Vargas, in New York, experienced a different outcome. He was infected with COVID-19 but survived. His voice inevitably cracks, and he cries hopelessly upon remembering.

“I had a fever. I had no appetite. I haven’t eaten in more than two weeks. I couldn’t sleep at night, and sometimes, I don’t know if it was because of the fever, I was hallucinating,” he recalled through tears.

Sánchez Vargas had and survived the virus, but is not satisfied with the way the government handles testing and contact tracing in the city. (Coral Murphy | Center for Investigative Journalism)

In his case, he called the New York City emergency number, but was never seen, despite reporting that he had symptoms of COVID-19. He went to a private doctor and paid for the test, which was positive. Two weeks later, the Government contacted him to find out if he had a car to take him to where they were doing the tests. There was never an effort to trace contacts and find out if his family was having symptoms.

The cases of these Puerto Ricans, aside from taking place in the three states with the largest Puerto Rican populations in the United States —Florida, New York, and New Jersey— also happened in three of the areas where there is the greatest possibility of contagion and death from COVID-19.

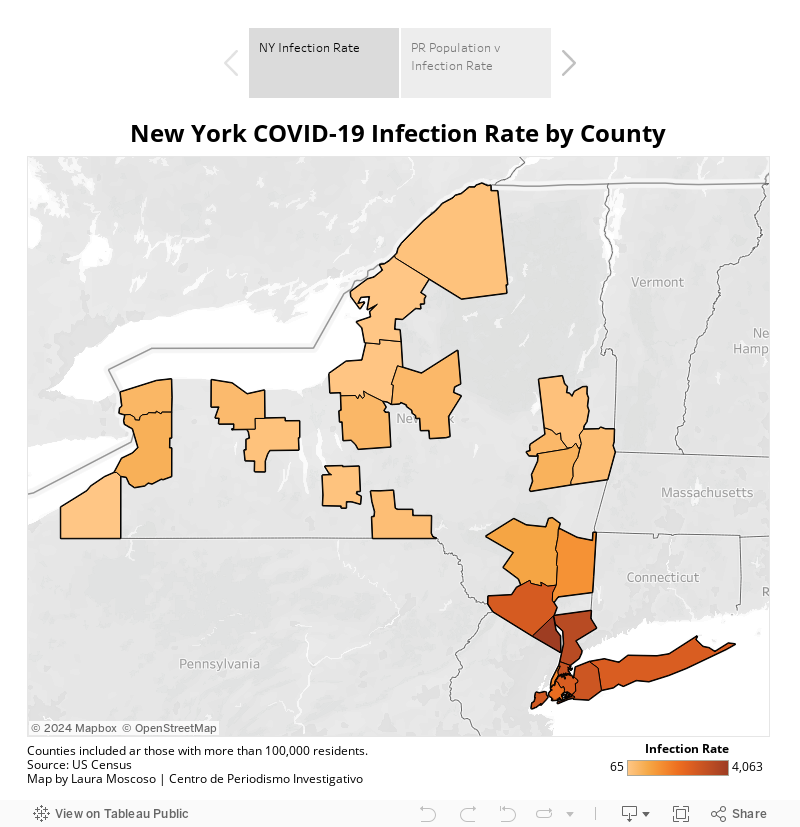

A Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI, in Spanish) investigation found that the geographical areas with the highest number of COVID-19 infections and deaths coincide with the counties with the highest proportion of Puerto Ricans in the United States. This trend occurs when analyzing the rates of infection and deaths in the 594 US counties with more than 100,000 inhabitants. Despite the trend, when looking at counties individually, there are some with a high proportion of Puerto Ricans but with low rates of COVID-19 infection and death. Likewise, there are other counties with a low proportion of Puerto Ricans but with high rates of infection and death.

It was not possible to determine if there is a higher number of infected Puerto Ricans when compared to other minority populations, since the nationality of those who have been tested for COVID-19 or who have died from the virus is not documented.

The investigation includes data available until May 31, which may vary when new information is registered with delay.

Puerto Ricans More Vulnerable in US Urban Areas

Puerto Rican populations in the United States live mainly in urban areas, according to Census data. In these counties, Puerto Ricans tend to face specific challenges, such as, being considered a racial minority, high unemployment, and limitations in English proficiency, the CPI found.

The counties with the most Puerto Ricans in Florida, New York and New Jersey are also the most socially vulnerable when compared to the rest of the counties in these states, the investigation uncovered.

For the analysis, the CPI used information from the Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) produced by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) based on Census data. This index evaluates 15 social factors grouped into four themes: socioeconomic level; housing composition; minority status and language; and housing type and transportation.

When reviewing the correlation between certain vulnerability factors and the rates of COVID-19 infections and deaths in counties with more than 100,000 residents, the conclusion was that it was not related to the phenomenon of poverty. It was related though to a particular type of poverty, urban poverty, according to Luis A. Avilés, a PhD in public health.

This is evident in Fresno County, California, an area with a high proportion of people living below the poverty level (28%), which has a low rate of COVID-19 infections and deaths. “The very nature of economic activities in Fresno, agricultural companies, suggests that contagion and deaths from this disease are increasing with urban poverty,” said Avilés.

“Contagion mechanisms are intensified by urban poverty, unlike what happens among poor workers in the agricultural industries. You have to remember that at the onset of discussions to reopen the economy [in the United States], it was believed that the agricultural and construction industries should open first because they represented a low risk of contagion,” said Avilés, who is also a biostatistician.

Poverty is measured based on a family’s income and the number of members, Avilés explained. For example, “a family of four earning less than $2,200 a month is considered to be below the poverty level.”

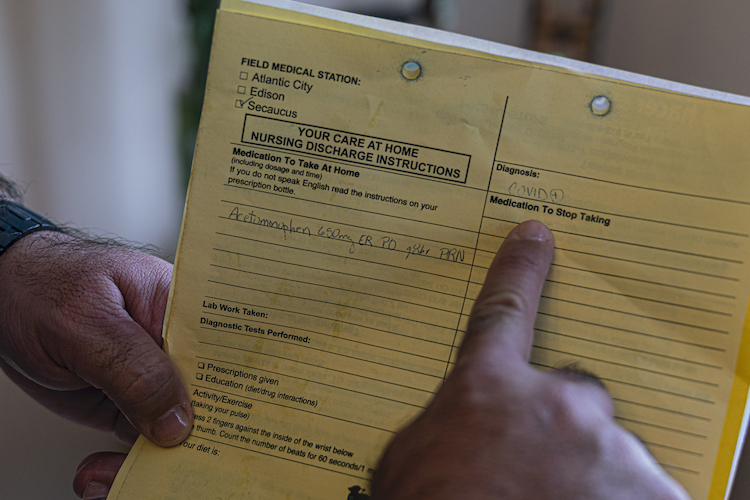

Typically, geographic areas with high levels of urban poverty coincide with a factor associated with COVID-19 infection: overcrowding, which occurs when there are more people than rooms in a house. People living in overcrowded conditions find it very difficult to practice social distancing, one of the main recommendations by entities such as the CDC and the World Health Organization (WHO) to avoid contagion.

John Lema, president of Latino Edification Multicultural Aid Center, north of Newark, NJ, explained that overcrowding is a challenge faced by communities in that area. Newark is a city in Essex County, where there is a large population of Hispanics, of which 7% are Puerto Rican.

“The levels of infection and contagion in these areas have been quite high, not because people have not followed the government’s rules, but because we have many buildings occupied by many families,” Lema explained, specifically referring to the area with the 07104 zip code, where the rate of infections until June was 2,972 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, and the death rate of 247, according to New Jersey Department of Health data.

Puerto Ricans Among the Populations With Highest Chances of Infection and Death in New York

William Sánchez Vargas is 57 years old and manages four apartment buildings for the elderly or disabled in the Bronx. He says that about 16 people have died there from COVID-19. He also learned about the death of at least 10 close friends.

New York is the epicenter of infections and deaths from this virus in the United States. The first case was reported on March 1. As of May 31, the number of infections in the state totaled 370,770, and 28,688 deaths. As of June, 17% of people killed by COVID-19 were African-American and 14% Hispanic, according to the New York State Department of Health. This data does not include New York City, where Latino and African American deaths from the virus are 34% and 28%, respectively. Although the rate of infection and hospitalization by COVID-19 is higher among the Black population, the death rate from this condition is higher in the Latino community in the city, where Puerto Ricans and Dominicans are the majority.

Héctor Cordero Guzmán, a doctor in sociology and demography, and professor at Baruch College at The City University of New York (CUNY), explained that this situation happens not just because of the number of Puerto Ricans and Dominicans in the area, but also because of the way in which they are grouped into specific communities and neighborhoods where they become the majority in those areas.

“When you’re the majority in a minority group, you have a higher risk of contagion due to the size of these populations. The counties in New York are low-income areas with a lot of social contact and with many people who are dedicated to the informal economy, selling on the street, cleaning industries, taxi drivers, among others,” Cordero Guzmán said.

He added that the way in which this state is organized in terms of housing, encourages communities, such as Puerto Ricans and Dominicans, to live in overcrowding, which prevents them from complying with social distancing. He also pointed out that due to the type of professions carried out by the residents of these communities, the option of staying at home “is a luxury they cannot afford.”

Sánchez Vargas was afraid to go to a hospital, because he knew of the collapse of the city’s health system under pressure with so many infections.

“Since there are so many cases in the hospital, they put you on a stretcher in a corner and, because maybe you don’t have many symptoms, they won’t pay attention to you and they will go tend to others who really need it; and they leave you there to die,” said Sánchez, who was born in New York, and has family in the central mountains of Adjuntas, Puerto Rico.

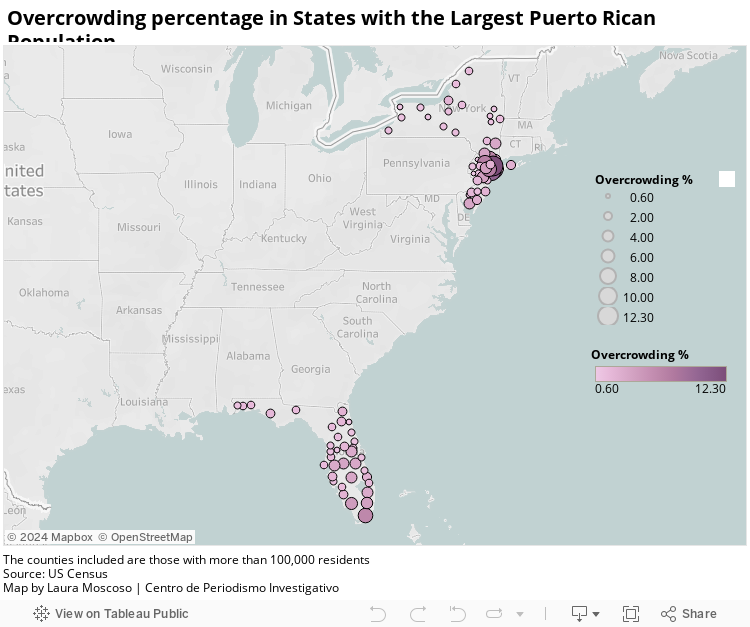

New York, where a million Puerto Ricans live, is the state with the strongest relationship between the proportion of the Puerto Rican population and the rates of infection and death by COVID-19 across the United States, the CPI found when applying the statistical formula called Pearson correlation, which measures linear correlation between two variables and establishes that a trend is strong if the result exceeds 0.50.

The coefficient in contagions was 0.56 in New York, while the death rate yielded a result of 0.71. Even excluding the Bronx, which is the New York county with the most Puerto Ricans (19%), the trend in infections and deaths remains just as strong.

Being considered a minority, not being fluent in English, not having a health plan, living in overcrowding conditions, and not having a high school diploma are factors of social vulnerability that could cause greater probability of contagion or death, the CPI found through interviews with Puerto Ricans in the three states, demographic data review, and by consulting experts.

“Hispanics represent the majority of deaths [in New York City],” Surgeon General Jerome Adams said during a press conference at the White House on April 10.

African American and Latino communities are more vulnerable to COVID-19 also due to pre-existing health conditions, Adams said.

According to the CDC, COVID-19 is a higher risk condition for older adults and people of any age who have serious illnesses.

Biostatistician Rafael Irizarry Quintero, a Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health professor, added that “in the United States, [preliminary] recent studies find that obesity is the strongest death predictor among COVID-19 patients. In the United States, obesity is more prevalent among people with low income.”

Adams said that African Americans and Native Americans “develop high blood pressure at much younger ages and it’s less likely to be under control and does greater harm to their organs.“

In the case of Puerto Ricans in the United States, Adams pointed out that these communities have high rates of asthma. According to 2017 data, 6.8% of adults over 18 in the Bronx have this condition. This county has the highest asthma rates, compared to Manhattan (4.6%), Queens (3.9), Brooklyn (3.7%) and Staten Island (1.7%).

By mid-May, 15,888 COVID-19 deaths had been recorded in New York City. Of these, 12,571 people suffered from some chronic health conditions such as diabetes, asthma, cancer, respiratory diseases, immunodeficiency, heart disease, hypertension, kidney or liver disease, and obesity.

The Bronx, New York’s Most Vulnerable and Affected County

The Bronx was the county with the highest COVID-19 death rate and the fifth highest rate of infection in the entire United States, as of May 31. The legendary neighborhood that has received generations of Puerto Ricans since the 1930s, which today represent 19% of its population, is also the most vulnerable county in New York, according to the SVI.

The director of the El Maestro Cultural and Educational Center, in the south Bronx, Fernando Laspina Franco, mourned the death of many of his acquaintances in the area. He remembered Puerto Rican boxer and coach Nelson Cuevas, who died in late March. In 1976, Cuevas opened the Apollo Boxing Club, where he trained the famous, such as Mike Tyson. In fact, Tyson paid tribute to Cuevas on his Instagram account.

Fernando Laspina Franco and Armando Pacheco Matos in front of the El Maestro Cultural and Educational Center in the Bronx. (Coral Murphy | Center for Investigative Journalism)

“We lost one of the best people in the boxing world. Nelson Cuevas died from complications with coronavirus. I had my first amateur fight at his Apollo Gym. I remember us kids would be so excited because when we had an exciting fight he would buy us soda and a mini hotdog in a biscuit because he knew we didn’t have money. Being around him during my amateur career was the best time of my life. Rest In Peace. End of an Era,” Tyson wrote.

Laspina Franco also suffered the loss of close relatives by COVID-19. “I lost 12 cousins here in the Bronx, and I lost my nephew, who passed away in Chicago,” he said.

Laspina Franco has lost more than a dozen family members and friends to COVID-19. (Coral Murphy | Center for Investigative Journalism)

He explained that they face multiple social and health challenges in his neighborhood. According to the SVI, 29% of the Bronx population lives below poverty levels, 12% is over 65, and 10% has no health insurance.

“Individuals we’ve found, who have diabetes and high blood pressure are at especially higher risk of bad outcomes from COVID, including dying,” said Dr. Oxiris Barbot, who is of Puerto Rican descent, and commissioner of the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, offering data that coincides with what the WHO has noted. According to the city, 36% of the population in the Bronx suffers from hypertension, 32% from obesity, 16% from diabetes, and 6% from asthma.

Puerto Ricans Survive as Best They Can

Richard López Rodríguez is a 35-year-old Puerto Rican who lives in Far Rockaway, Queens, and works as a doorman in a building on Fifth Avenue in Manhattan. His hours are 3 p.m. to 11 p.m. Since the pandemic and curfew began in New York, López Rodríguez has not stopped working, and commutes daily on subway’s A line.

“I take precautions for my brother, who is handicapped. I’m the one who exposes myself daily when leaving and returning. Except for that, my family stays at home, locked up, watching out that no one gets sick, especially my brother, because since he can’t speak, it would be hard for us to know if he got sick with this condition,” said López Rodríguez, who lives with his sister, his three nieces, and his brother.

Richard López Rodríguez

Like other marginalized groups, Puerto Ricans living in New York are not exempt from the racial and class disparity reflected in the COVID-19 crisis in this state. They are more exposed to contagion because many have been unable to stay at home due to the type of work they do, such as taxi drivers, delivery services, cooks, among other tasks considered essential during the pandemic. López Rodríguez, for example, watches over the entrance to a 16-apartment building, where some owners left to isolate in their second homes during the pandemic.

“They’re multi-millionaires who don’t take risks. Many have left the city for their mansions [outside the city]. [Others] used to go out to walk the dogs, but they’re not even doing that anymore,” he said.

Doormen were included among the essential jobs mandated by an executive order that Gov. Andrew Cuomo issued on March 20. However, the CPI found that the job was removed from that list later that same day.

In mid-June, Service Employees International Union (SEIU) local 32BJ reported the death of 132 members related to COVID-19. This labor group represents 175,000 doorpersons, janitors, security officers, and airport and restaurant workers on the East coast. Its President, Kyle Bragg, said that among the duties of the doorpersons is to give access to the buildings, which is part of security. He added that the majority of union members are immigrants and Black people who live in low-income neighborhoods and have been the most affected by the pandemic in New York.

“While essential workers are keeping others safe, they and those close to them are getting sick and dying,” he said. By traveling on public transport, this working class is more exposed to contagion, he added.

The effects of the pandemic have also taken a toll on the routines and finances of Puerto Rican families living in New York and bring to the forefront how they experience life from vulnerability there, as a minority, due to language obstacles and the type of vertical housing that prevails in the city. Unemployment, which reaches a rate of 10% among Puerto Ricans in New York according to 2016 data from the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, is also a factor.

Milagros Cancel Ruiz, a native of Mayagüez, lives in a one-bedroom apartment in the Bronx with her three children with autism. She uses the bedroom and her children sleep in a bunk bed and a sofa bed in the living room. Two birds also live there, which, in addition to being the family pets, help keep the children calm, says Cancel Ruiz.

Milagros Cancel Ruiz tries to keep her three children busy with daytime activities from the one-bedroom apartment where they live in the Bronx. (Hiram Alejandro Durán | Center for Investigative Journalism)

Staying at home, as the authorities have requested, has represented a greater expense due to the need to buy protection and cleaning items and groceries, which is a challenge for this Puerto Rican mother who since November 2019 has been unemployed.

“If you don’t spend that additional [money], how are you going to protect yourself? Because right now, no Government is coming here to the community to say: “Take this mask, take this alcohol or take what you need.” That comes out of your pocket,” said Cancel Ruiz, who only has “the aid that any unemployed person gets.”

“It’s a little bit difficult, especially now to pay for rent, because you have to use that money to be able stock up on the things you need most. Now you have to spend more money on groceries because you cannot be going out every day. Everything gets more expensive. If groceries were $100 before, now it’s $150 or $200,” she said, for example.

Cancel Ruiz also said it has been a challenge to take care of her children’s emotional health considering the radical change of having to take their classes and therapies in a different environment.

Two of Milagros Cancel Ruiz’s three children, Edwin Sanabria (left) and Giovanni Cancel (right) in the bed they share in the living room. (Hiram Alejandro Durán | Center for Investigative Journalism)

“You have to prevent them from falling into depression. You always have to be doing things, continually getting involved in positive things and being alert all the time, which is not easy. Be healthy, take care of yourself first to take care of the children. COVID-19 has not been easy on the life of anyone, especially in my life, because everything in their routine changed. Now everything is done at home. The therapies are done at home. Now everything is virtual,” she said.

The Situation in Florida

Jimmy Santiago, 55, worked part-time at Managed Labor Solutions, which provides transportation services to car rental companies at the Orlando Airport, in Florida. Tasks included moving rental vehicles to where they are cleaned and taking company employees to the vehicle fleet lots.

“He took his job very seriously. He liked it because it kept him busy,” said his widow Marisol Romero, to whom she was married for 11 years.

That commitment to the job kept him going back despite the first news stories warning about the increase in COVID-19 cases in the area.

“I was very worried about him because he had a heart condition. The company was extremely irresponsible. When the news of the pandemic came out, he didn’t have any type of protection,” said Romero, a native of Guayanilla.

When he began to feel ill, Santiago, a native of Peñuelas, went to the hospital, where he tested negative for influenza. They did not test him for COVID-19.

“After that, he started to feel better. On the second day he went to work. But when he came home, he felt worse. He went to the doctor again and they changed his medicine. I saw that he was weak, he was barely eating,” Romero recalled, still shocked by the loss. They lived with two children and a grandson.

At 2 a.m. on a Thursday in late March, Santiago asked his wife to take him to the hospital, as he felt very sick. It was his daughter who took him to Osceola Regional Medical Center, since Romero is a cancer survivor and her family did not want her to be exposed to the virus.

“They did the COVID test, but after five days they had not given me the result. The nurse didn’t know how it got lost and it had to be done again. But he was already in very bad condition. He would call me and tell me he could no longer breathe,” Romero said.

Santiago’s clinical case became complicated and they had to intubate him. His death certificate said that his passing was associated with complications from COVID-19 and respiratory failure.

After her husband’s death, Romero contacted Managed Labor Solutions to alert them of the situation. Although she spoke to two employees, she said company managers never contacted her or took corrective action to protect the other employees.

“As a responsible person, I called the company, because I know that after a patient is diagnosed with COVID, everyone around them has to be quarantined. I know that he worked in a group. What the company did was remove him from the list, because if an employee is absent for a few days, they remove them,” she said.

The CPI contacted Managed Labor Solutions five times, but they were not available for a reaction.

Meanwhile, the Greater Orlando Aviation Authority, which operates the airport, said through the manager of public affairs Caitlin Dineen, they “cannot speak on behalf of a third-party contractor.”

The first case in Florida was reported on March 1. As of May 31, this state had 56,077 positive cases and 2,451 deaths on record. By that same date, 36% of positive cases and 22% of deaths were of Hispanics.

Despite the fact that Florida is the state with the highest Puerto Rican population (1.1 million people, according to the Census), when analyzing all its counties, no relationship was found between the proportion of Puerto Ricans and the infection and death rates, as in New York.

On May 18, Florida entered the first phase of reopening certain companies and businesses, as Gov. Ron DeSantis announced. After that date, state authorities have reported a rebound in COVID-19 infections. On Monday, June 22, Florida exceeded 100,000 infections. The CPI analyzed the data through June 21, but —like the previous observation— no relationship was found between the rates of infection and the proportion of Puerto Ricans in that state.

According to Avilés that is because contagion in Florida responds to gatherings that occur in places such as beaches and churches, and not in areas where more Puerto Ricans live.

“You have to see if those places are near Puerto Rican’s neighborhoods, or if Puerto Ricans visit there. [As of June 21], the counties with the highest [rates of] infections —Martin, Miami-Dade, Collier and Palm Beach— are on the coasts with beach access. So, there’s no correlation because this increase typically occurs in places where there aren’t so many Puerto Ricans,” the biostatistician concluded.

Meanwhile, sociologist Cordero Guzmán said Florida has a different urban structure than New York.

“You have to look at the concentration and spread of these populations in both states. In New York, we speak of a greater geographic concentration living in buildings with multi-generation families. In some communities in the Bronx, Puerto Ricans live in houses, but further south of that county, the trend is that they live in buildings. In Florida’s case, Puerto Ricans are more spread out and social contact could be lower,” the CUNY professor said.

On the other hand, epidemiologist Cruz María Nazario stressed that the problem with the spike seen in Florida is that the virus will ultimately continue to affect minorities in that state.

“The hypothesis is that, given the lack of control that has taken place in Florida, it’s very likely that the infection and death rates in those populations that are most vulnerable —Latinos— could increase. This hypothesis is based on the fact that, as opposed to the groups that are in better socioeconomic positions, minority groups cannot stay at home, work remotely and, above all, don’t have adequate health insurance, their employers don’t pay sick days, and force them to go to work even if they’re sick,” the expert explained. The leisure and hospitality and the health services are among the top five industries where Hispanics work in Florida, according to 2018 data from the US Department of Labor.

Unemployment and Hunger

As of May 31, the highest rate of infections in Florida occurred in Miami-Dade (663 infections per 100,000 inhabitants), where the proportion of Puerto Ricans is 3.69%. The county with the highest percentage of Puerto Ricans was Osceola (32%), and its infection rate was 207 infections per 100,000 inhabitants.

When evaluating the rates of infection and deaths from COVID-19 in Florida, it is evident that being a minority, overcrowding, limitation with the English language, not having medical insurance, and not having a high school diploma are the most prevalent social vulnerability factors.

In addition to these factors, Puerto Ricans are also more vulnerable due to poverty compared to the rest of the population. Osceola, for example, ranks third in counties with the highest social vulnerability score. According to the CDC, this county has 16% poverty, 10% does not speak English, 16% does not have health insurance, and 67% is considered a minority group.

The unemployment factor did not draw a parallel with COVID-19 deaths and infections in the general population, according to the calculation of the Pearson coefficient. However, a small connection was found between this factor and the proportion of Puerto Ricans in Florida.

When looking at the Florida Department of Labor statistics, in May, this state registered 850,400 fewer jobs compared to the same month in 2019. The hospitality and leisure industry was the most affected with the loss of 460,500 (-37%) jobs. Osceola and Orange counties —where the most Puerto Ricans live— had the highest unemployment rates, at 31% and 23%, respectively.

Denisse Centeno Lamas, a Puerto Rican who lives in Florida, is an example of how the virus crisis affects jobs. As executive director of Hispanic Family Counseling —an organization with a presence in several Florida counties that offers mental health services— she had to lay off 80% of her administrative employees to avoid a shutdown and to continue offering the therapies.

“It was a very difficult and frustrating situation for me because the truth is that my employees are excellent. They are passionate about what they do. It’s very tough, very sad, but I really could not pay them. It would’ve been worse to have them come to work and then not pay them,” she said.

Deborah Oquendo, 44, a native of Bayamón, was laid-off on March 25 from her job at the Orlando airport. Oquendo was one of thousands of Puerto Ricans who emigrated to the United States in 2017 after Hurricane María.

Deborah Oquendo with her family at her home in Orlando, Florida.

She lives with her husband, daughter, and her 76-year-old mother in Orlando, in Orange. Since being laid-off, Oquendo has been caring for an elderly person who lives in Tampa, almost a two hours ride from her home. She does that from Tuesday to Saturday. To make ends meet, Oquendo landed a part-time job at a pool maintenance company that services apartment complexes in Orlando. She works there between 3 a.m. and 5 a.m., and then she goes to Tampa.

Oquendo is aware of the risks of going outside and is concerned about her mother’s health, that of the lady she cares for, and for her 3-year-old daughter’s. But she needs the income for her family’s expenses.

Another challenge Puerto Ricans in Florida face in the context of COVID-19 has been access to food, several interviewees said.

This reality led Father José Rodríguez, from the Jesús de Nazaret Episcopal Church in Orlando, along with other people in the community, to create a food bank that they provide to people via a drive-thru. So far, they have donated groceries to more than 250 families.

Linda Pérez Dávila, president of the Boricuas de Corazón organization, agreed that access to food is one of the challenges Puerto Ricans in Florida face during the pandemic. In her case, the group has provided assistance to more than 500 people, thanks to the help of other nonprofit organizations in Osceola, Orange, Hillsborough, and Pinellas counties.

“Many say, ‘Why don’t they have anything to eat if they got $1,200’ [referring to individual federal aid due to the pandemic]. But the money hasn’t reached everyone. [Also], they have been out of work for more than five weeks. There are 70% or a little more [of people] who have not received a paycheck. Very few employers received the small business incentive to pay them and retain them as employees. The first thing they will do is satisfy their hunger and that of their family. They will spend the little money they have on food,” said Pérez Dávila, who founded the organization in 2018 as a result of the efforts she oversaw from Florida to help Puerto Rico after Hurricane María made landfall in 2017.

New Jersey Latinos Most Vulnerable to Infection and Death

Since COVID-19 began to surface in the United States, New Jersey has been in second place with the highest number of virus-related infections and deaths. On March 4, this state reported the first two cases, and as of May 31, it has accumulated 159,575 positive cases and 11,696 deaths.

According to that state’s Department of Health, until then, people who were infected were 30% Latino and 17% Black, with Latinos also ranking first in COVID-19 deaths in this state (19.40%), according to data as of June.

More than 488,000 Puerto Ricans live in New Jersey, according to the Census. The CPI found that the counties with the most COVID-19 infections there coincide with the areas with the highest Puerto Rican populations, but it is a slight trend. However, no trend was found between the proportion of Puerto Ricans and the rate of death.

Mike Ruiz Rivera, 42, is from Ponce, Puerto Rico. He currently lives in Newark, in Essex County, which has the highest death rate from COVID-19 on record. More than 55,000 Puerto Ricans live in this county. It is the second most vulnerable county in New Jersey, according to the SVI. There, 16% of its population lives in poverty and 69% are from marginalized communities.

Mike Ruiz in the room at his home in Newark, New Jersey. (Hiram Alejandro Durán | Center for Investigative Journalism)

Living in poverty, not knowing English, overcrowding, being a minority, not having health insurance, and not having a high school diploma are the vulnerability factors that most affect this state’s population. Considering the SVI indicators, unemployment and having a disability also impact the Puerto Rican population. The Census considers disability as difficulty in hearing, vision, cognitive, ambulatory, self-care, and independent living.

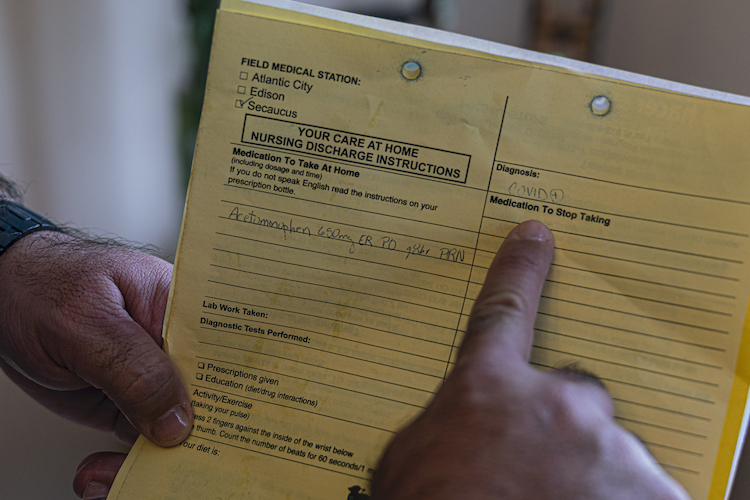

Ruiz Rivera is a plumber. Today, he can tell the story of how he survived COVID-19 after spending 20 days in the hospital and was about to be intubated to breathe. He suffers from asthma and, knowing what was happening with the COVID-19 virus, he locked himself in his room. Days later he went to a doctor’s appointment when he learned that his temperature was in the 100s. They put him in quarantine and on March 30, he remembers that he was about to collapse, and the fever would not break. He asked his mom to call an ambulance and that’s how he ended up in the hospital.

Ruiz shows the discharge papers from the hospital, with the COVID diagnosis (Hiram Alejandro Durán | Center for Investigative Journalism)

“When you got to the emergency room, it was like being in a war movie. You saw all the sick people around you as you passed through. They put me in a room alone. I spent a day there watching people fighting for their lives, screaming, coughing loudly,” he said.

He had a fever of between 102 and 103 degrees for eight days. They did not have to intubate him, and he slowly recovered until he was released on April 19.

“[COVID-19] is the worst thing a person can get. When I got to the hospital, I was traumatized. So, when they told me that they were going to intubate me, I had already seen people they had intubated, who in two days were out of it. I was afraid and said: ‘They’re going to intubate me; I’m going to die.’ I had that on my mind, and I traumatized myself even more,” said Ruiz Rivera.

METHODOLOGY

The United States has 3,142 counties, according to the Census. Of those, about half are small counties that usually have a very small Puerto Rican population. To standardize the analysis, counties with more than 100,000 inhabitants were chosen for a total of 594. The number of infections and deaths in these counties was obtained from the daily report by USAFacts, a nonprofit initiative dedicated to historical and state-by-state data collection. The analysis spanned from January 22 to May 31, 2020. On the CDC’s standard form to collect data on COVID-19, known as PUI (Person Under Investigation), only racial and ethnic identification is required. Therefore, for this research, a geographic analysis was made, focused on places and not on individuals.

[…] the lack of a comprehensive federal response to COVID-19 has been disastrous to Puerto Ricans both on the island and stateside. Biden has the experience and a comprehensive plan to fight COVID-19 from a scientific […]