By G. Cristina Mora, Claudia Sandoval, and Sylvia Zamora

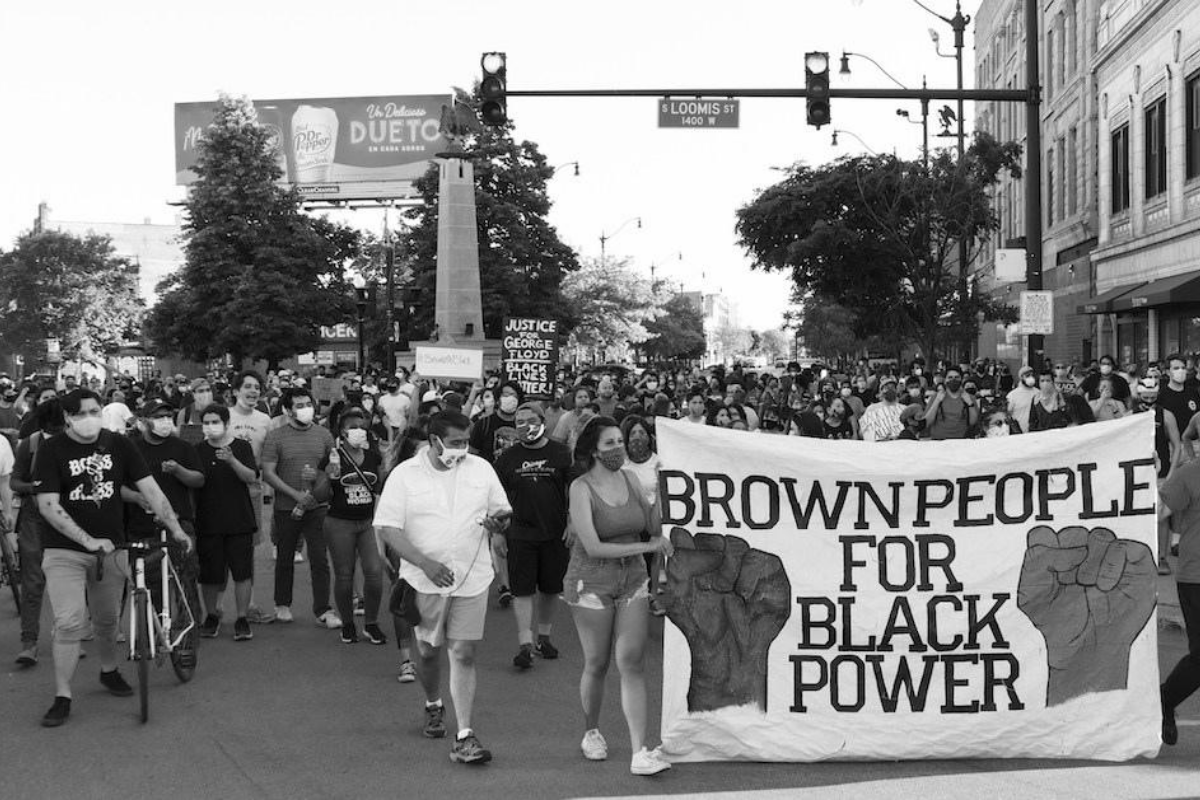

As the 2020 election approaches, voters’ ability to see inequality and systemic racism will be consequential for enacting social change through the ballot box. This means understanding personal experiences and community patterns as not simply random, individual occurrences, but as fundamentally linked to larger systems of bias and inequality against people of color. Time and again, history shows us that Black Americans have an understanding of institutionalized racial disparities. However, as COVID-19 and attention to police brutality grip the nation, many Latinos have yet to fully grasp these structured, racial insights even though their communities suffer disproportionately.

For example, take the issue of COVID-19. It is now well known that Latinos, like Blacks, are contracting the virus and developing more life-threatening complications at much higher rates than whites. As essential and front line workers, Latinos also bear a disproportionate share of the wage and job loss caused by the pandemic. Media stories of Latino death, suffering, and economic vulnerability abound. Accordingly, a recent survey conducted by the University of California, Berkeley reveals that Latinos, more than any other group, believe that COVID poses a major threat to their family’s health and economic wellbeing. Latinos see and feel the painful effects of Covid-19 in their lives.

Yet when asked whether they think that the virus disproportionately affects Latinos and Blacks, Latinos are less likely than other groups to agree. Indeed, the UC research survey shows that the vast majority of Blacks in the state (72%) and a substantial majority of Whites (65%) agree that the virus impacts Black and Brown communities more, but Latinos fall behind at 60%. In other words, in their day to day lives, Latinos are feeling the devastating effects of the virus, but they have a long way to go in recognizing how this hardship is connected to structural and racial patterns of inequality that affect communities of color.

And while, yes, it is true that the virus has “no eyes” and can affect everyone, Latinos are not necessarily understanding that their position, as economically precarious, as subjects of an unequal healthcare system, and as a racially targeted community, has consequently placed them among the most vulnerable groups in the nation.

Similarly, when we consider policing and racial justice, reports show that Latinos, once again, are disproportionate racial victims. National data shows that Latinos are killed by the police at almost twice the rate that whites are, a finding echoed in the narratives within Latino communities about hyper policing, racial profiling, and the recent police killings of Eric Salgado, 22, Sean Monterrosa, 22, and Angel Armenta, 23 in California this year.

Yet survey data show that Latinos are less likely than others to think about policing as a racial justice issue. When respondents were asked whether they agree with the statement, “Compared to Whites, Blacks face more police violence,” we see that a vast majority of Blacks, 92%, agree compared to 75% of whites and 67% of Latinos. More importantly, when asked whether, “Compared to Whites, Latinos face more police violence,” Latinos are the least likely to agree with this statement. In fact, Black respondents are significantly more likely than Latino respondents (90 v. 71) to say that Latinos face disproportionate police violence. This 19-point gap between Blacks and Latinos on the question suggests that Latino respondents are more similar to whites in their view of police violence than to Black Californians, despite the vast racial disparities and closer structural conditions with Blacks on these issues.

Some might ask: If Black Americans are demonstrating a deep understanding of the ways that the system has embedded racial inequalities, why are many Latinos failing to do the same? This question has plagued Latino advocacy groups for decades, and the answer may have to do with messaging and the tough community conversations about race, and racism, that still need to be repeated—in Spanish-language media, in church groups, and at our kitchen tables. Let’s remember that this historic moment presents an opportunity for America to act on issues of racial justice in a meaningful way.

Latinos need to be part of this effort and remember that the upcoming elections will determine not simply the presidency, but also local-level policing and public health policy that disproportionately affect communities of color. Black Americans already see these structural inequalities clearly.

It’s time for Latinos to do the same.

***

Cristina Mora is Associate Professor of Sociology at UC Berkeley and Co-Director of the Institute of Governmental Studies. She is the author of Making Hispanics: How Activists, Bureaucrats, and Media Constructed a New American (University of Chicago Press), which provides a socio-historical account of the rise of the “Hispanic/Latino” panethnic category in the United States.

Claudia Sandoval is Assistant Professor of Political Science at Loyola Marymount University specializing in American politics, Black/Latinx Relations and the politics of Immigration.

Sylvia Zamora is Assistant Professor of Sociology at Loyola Marymount University specializing in African American and Latino relations and Mexican immigration.

maybe if more illegal immigrants worked on the books, and/or didn’t send so mush of their money back home, wed have more money to put into our unfait health system. which is free for them. by the way. smh

[…] into the information. However Latino anti-Black racism just isn’t new or shocking. Plenty of scholars have examined the battle between these two teams, together with Efren Perez and colleagues, here at […]

[…] the information. However Latino anti-Black racism just isn’t new or stunning. A variety of scholars have examined the battle between these two teams, together with Efren Perez and colleagues, here at […]

[…] comments burst into the news. But Latino anti-Black racism is not new or surprising. A number of scholars have examined the conflict between these two groups, including Efren Perez and colleagues, here at […]