Jennifer Lopez performing at the Video Music Awards in New York City, on August 20, 2018. (MTV International/CC BY 3.0)

My first experience that led me to critically reflect on the word “negrito/a/x” took place in a theory of history course I took in 2010 at the University of Puerto Rico-Río Piedras.

At that time, I was already critiquing all the ideological conventions of racial mixture which was hard to miss: there were barely any Black professors or students at UPR, local channels didn’t have a single Black television talk show host, students made racist remarks all the time, and they got away with it. (A couple of years before, Tego Calderón’s album, El Abayarde, was released altering our understanding of Black Puerto Rican racial pride.)

In the classroom, a good friend of mine said the word “negrito” in a sentence when he was referring to a friend. The whitest Puerto Rican professor you could imagine (whom I have a lot of respect for up to this day) interjected while sitting behind his desk in front of the room and pulled up his hand to his side as if he was measuring a child.

“Was he this tall?” he asked my friend.

My classmate chuckled and replied, “No, I meant negro” and continued to make his point.

The fact that he referred to his Black friend as a small Black child wasn’t his fault. We were both from working-class parcelas (ghettoes) and using that kind of language was normal to us. Of course, at that time I had heard other Black artists like Don Omar use the word “Negro” in his songs like “Conteo,” “Repórtense,” among others. For example, in his song “Yo Puedo Con Todos” he says:

El Negro sin celos

Y a tu lao’ con las modelos

Y por mi culpa, muchachos

Ustedes no ven un pelo

El Negro de Carola

Quien menea la bola

Con el que está conspirando

Pa’ tumbarle la chola

After witnessing that incident in the classroom, I started to wonder what was the difference between Black Puerto Rican people referring to themselves as Black in comparison to non-Black Puerto Ricans calling themselves and others “negro/a/x” and “negrito/a/x.” This rumination reminded me of a movie I saw when I was about 11 years old in Puerto Rico. I can’t remember the name of the movie, but I remember a scene where the white plantation owner was saying to a Spanish visitor in Puerto Rico, “You don’t know what it is to go through a hurricane.” Within that conversation, he calls on one of his enslaved Black workers by calling him “Negro.” I wondered if that Black guy had a name. Nowadays, we know about Black maroons and enslaved Africans in Puerto Rico who were further dehumanized by being called “moreno” or “negro,” and not their proper names.

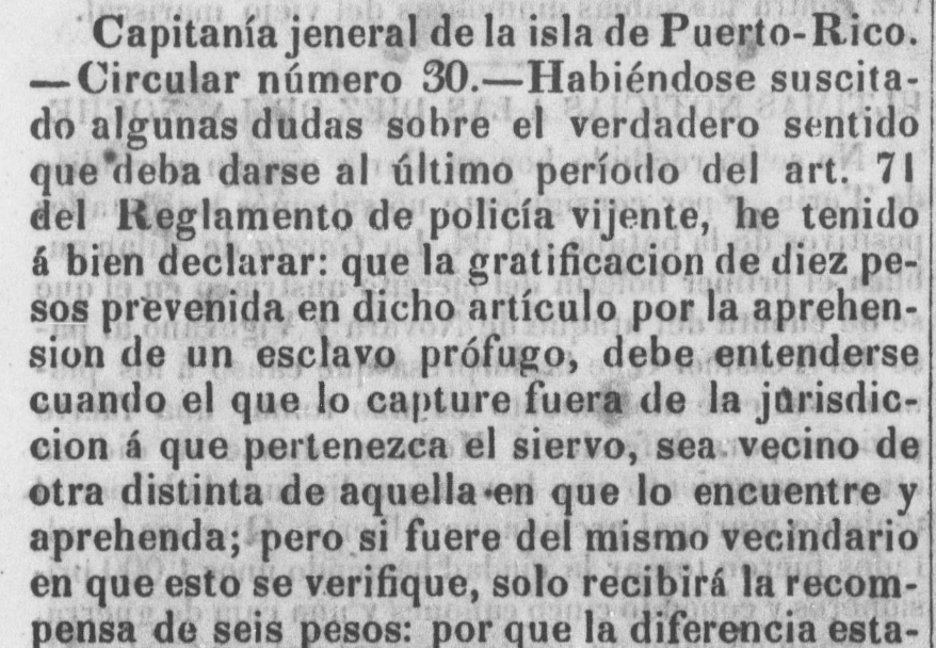

Ads offering rewards for marooned enslaved Black peoples was common back then in Puerto Rican newspapers, which makes me wonder if non-Black Puerto Ricans used to call each other Negro/a or Negrito/a for endearment as well back in the day. Probably not, especially when Black bodies are being hunted and treated like cattle. It doesn’t matter if slavery in Puerto Rico was 14 percent or 5 percent. What matters is the psychological association of the Black body and referring oneself as Black without having to deal with actually being Black. I wonder if non-Black Puerto Ricans feel some type of shame when they say “Our Black people are different,” which a white Puerto Rican scholar and activist had the audacity to tell me in Humboldt Park a couple of years ago.

‘Tu Negrita del Bronx’

So when I heard about last week’s Jennifer Lopez (JLo) controversy of calling herself “tu Negrita del Bronx,” I decided to play the song “Moreno Soy” by Luigi Texidor in my car while driving to the gas station.

It reminded me of his live soneo (salsa singing with acapella rhymes) where he was making fun of his own Blackness while also affirming his Blackness even if they cut his leg, like they did to Kunta Kinte.

Artists like Ismael Rivera —among others— have affirmed the word “Negro” to mean the Black experience. If Black Puerto Ricans have affirmed the word “Negro/a/x” in Puerto Rico and the diaspora for such a long time, why can’t non-Black Puerto Ricans respect that?

Does it affect their Puerto Ricanness? Does claiming to be Black on the inside at the expense of invisibilizing Black people worth it?

If JLo is a “Negrita del Bronx,” then what do we call a Black Puerto Rican woman from the Bronx?

When I hear Texidor’s song, I feel proud of my melanin and I lament Black Puerto Ricans like my father from Santurce who sought to improve the race by marrying a white Puerto Rican woman from Utuado, as he did in previous marriages. We should ask non-Black Puerto Ricans: Why is invisibilizing Black people by claiming to use such an adjective so freely for the sake of your Puerto Ricannes mean to actual Black people? Do you get called Dominican after you’ve said you’re Puerto Rican like 10 times? Do you get called Negro cepillao out of nowhere because you are Black person with “good hair?” Did you get made fun of—like my Black cousin by my deceased white brother in Toa Baja? When my cousin would come to visit, my brother would sing, “Here comes Jonathan” to the tune of the “Men in Black” theme song, or he would call him “carbón” (charcoal). Even though my brother had two Black siblings, it didn’t stop him from being an anti-Black racist towards my cousin.

Blackness as a Joke

There are many studies about this happening everywhere in Puerto Rico. A recent study found the following:

“’Blackness is a joke for Puerto Ricans, Blacks make them laugh (le damos pavera). It is as if the darker we are the funnier we are.’ Some people mentioned ‘social circles’ as a source of racism writing simply ‘among my social circles.’ Others mentioned that they had experienced racism as part of life in a mixed-race couple. One respondent wrote: ‘I have two daughters and they have skin that is darker than mine, their dad is Puerto Rican like me, but people often ask me if they are my daughters.’ And another commented, ‘My husband was Black and I am white and everyone stared at us.’”

Blackness is also a joke when it used to invisibilize Black bodies and then claim that Negrito/a is “a form of endearment.” I wonder if the people who don’t mind getting called Negrito/a would like to also deal with the actual structural and interpersonal racism that comes with claiming Blackness?

Another major issue with JLo’s comments is that it makes it harder for Afro-Latinas/os/xs in the United States to make their case for equity when they are already severely ignored in mainstream media and in policies in the country.

In addition, although I have issues with the extreme patriotism some Black Puerto Ricans express, I can see why Black people sometimes have to stand up for their own Blackness within the realm of nationalism. However, non-Black Puerto Ricans and their claims to “Blackness” should not deter them from envisioning their Blackness without the Puerto Rican flag.

As such I wonder what it means to use the word “negrito/a/x” so loosely among Puerto Ricans that derives from people who were dehumanized and objectified into producing commodities? Similar to other words like Boricua, are we honoring natives by calling ourselves Boricuas or does it make more sense to honor people by not claiming to be them and understand their experiences? This seems to be the central problem—for Puerto Ricans Blackness is an extension of Puerto Ricanness. Many don’t know how to recognize Black Puerto Ricanness as a phenomenon that needs to be acknowledged without having to see yourself in those Black experiences.

Most of us have very little knowledge of Puerto Rico prior to the U.S. invasion of 1898. Some behave as if 1898 is the date when Puerto Rican history begins to matter. Contrastingly, I’m always thinking about Puerto Rican history and varied stories prior to 1898. I always wonder what it would be like to be in horse carriages in Puerto Rico and pass by enslaved populations. The recent uncoverings of Black cemeteries gives a horrific revelation of a Puerto Rico very different than the one we imagine after 1898.

Pre-1898 is a time when everyone was already allegedly mixing freely and living in harmony. Although many historians will say that slavery never exceeded 15 percent or that many Black people were already freed (libertos), I still think they miss the point. I still love thinking about Marcos Xiorro’s slave insurrection conspiracy in July of 1821 that got him killed because another enslaved man called Ambrosio decided to snitch. We still have a lot of Ambrosios who are the first ones to attack Black Puerto Ricans trying to demand change. As such, I like to imagine the moments Marcos didn’t identify his Blackness with a Puerto Rican flag or with a need to contrast himself with the United States. He was an enslaved Black man that wanted to revolt for the sake of his own freedom and fugitivity. The word “Negro/a/x” for him must have meant something different and I personally would like to honor the signifier “Black” for people like Marcos and not any random person from Puerto Rico.

Who Gets to Claim Blackness?

In closing, there is a need to create historical literacy in schools, social media, public humanities and the media industry that centers Black experiences before and after the U.S. invasion of 1898. We need to create ways for non-Black Puerto Ricans to listen to songs like “Nací Moreno” without having to claim they are one of the morenos. I guess this is the problem, songs like “Nací Moreno” under the mestizaje guise of salsa, and now reggaetón, have been engulfed by the music industry to commodify Blackness as an extension of either Puerto Ricanness or Latinidad.

In the video performance titled “You Don’t Look Like,” Black Queer performer Javier Cardona makes fun of the stereotypical roles he gets in the entertainment industry—roles that are reserved for Black people. In the performance, Cardona makes the crowd say “bunda bunda agua” (which has no actual meaning in Spanish) while staring at themselves in a mirror. What is Cardona trying to convey? Why does he paint himself in Blackface and complains about not looking Puerto Rican enough for the entertainment industry? Perhaps JLo should stare at herself in a mirror and say “bunda bunda agua” and reflect on all the roles she has received she wouldn’t have received otherwise had she been a real Negra from the Bronx.

As such, that is where JLo lies in her comment, an attempt to claim herself as a Negrita as a form of endearment without any regard to the struggles of Black Puerto Ricans, and especially, that of Black Puerto Rican women.

We should ask her a question similar to that of my professor’s: Are you a small Black girl? Do you think you’re honoring people like Marcos Xiorro by claiming a lived experience that isn’t yours? Are you being endearing to Black people that way?

This is much deeper than a “term of endearment.”

***

William García-Medina is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of American Studies at the University of Kansas. García-Medina’s research currently focuses on Black ethnics and the construction and social reproduction of Black American racial identity discourse in the public humanities. In 2016, he earned an MA in Curriculum and Instruction from Teachers College–Columbia University in New York City with a focus on historical literacies in elementary schools. He also has an MA in history from the University of Puerto Rico-Recinto de Río Piedras. He has been contributing to Latino Rebels since 2015 and has made appearances on Latino USA, NPR and the Howard Jordan Journal. He tweets from @afrolatinoed.

I’ve always considered negrito/a not simply a term of endearment but also an acknowledgement and point of pride of our shared African heritage. The majority of Puerto Ricans are not white or black, they are mulato-mestizo, a mix of European, African and indigenous races (in my own case, this includes Asian/South Pacific). But it sounds like the author sees the P.R. race issue in strictly black and white terms. There’s no discussion of the mulato, mix-race culture. JLo is mulato so her calling herself negrita is not far fetched. She may not be Black but I seriously doubt that she’s never been the target of racism herself or that she’s so clueless to be devoid of the struggles of Black Puerto Ricans. (If there’s any doubt, take a look at all the artists that she’s collaborated with over her long career.) Being Puerto Rican alone makes you a target, whether you are white, black or mulato. Nevertheless, Puerto Ricans have all have a long-way before they can call themselves color-blind.

The problem is that Puerto Ricans raised/living in America view blackness from a viewpoint established by the people who conquered and divided them.

There’s an unspoken bias by islanders toward those born on the mainland. It’s actually a projection of a second-class mentality, an inferiority complex which comes out of colonial subjugation. I was born in PR and have lived both on the island and the mainland. One of the problems is that we continue to use the colonialist terms (negrito/a being one of them) to describe ourselves and our fellow countrymen (and that includes all parts of Latin America as well). It’s been a long time since the days of slavery and plantations but we still insist on using these terms…which frankly strike me as triggers. Maybe it’s time to refute these terms? Or, we acknowledge the inherent prejudices within them and turn them on their head the way that Black Americans employ language. They don’t tear each other down because they are darker or lighter. They celebrate their differences.

“mulato” u caint b seeryus, that wuzznt an acceptable term n 1920 let alone 2020

Yea, it’s as bad as negrito. All of these racial classifications and colonialist terms need to go.

[…] Lloréns: It is true that the use of “negrita/negrito” to refer lovingly or kindly to 1 one other is widespread amongst Latinxs, regardless of race or bodily look. It is commonly claimed that the tone of voice of the particular person talking it reveals the intention of utilization, however simply because one thing is widespread doesn’t make it acceptable. […]

[…] Lloréns: Es cierto que el uso de negrita/negrito para referirse con cariño o amabilidad a los demás está muy extendido entre los latinos, independientemente de la raza o el aspecto físico. A menudo se afirma que el tono de voz de la persona que lo habla revela la intención de uso, pero solo porque algo está extendido no lo hace aceptable. […]

[…] “It is true that the use of ‘negrita/negrito’ to refer lovingly or kindly to one another is widespread among Latinxs, regardless of race or physical appearance,” Hilda Lloréns a cultural anthropologist and associate professor of anthropology at the University of Rhode Island told the San Diego Union Tribune. “It is often claimed that the tone of voice of the person speaking it reveals the intention of usage, but just because something is widespread doesn’t make it acceptable.” […]

[…] Lloréns: It’s true that the usage of “negrita/negrito” to refer lovingly or kindly to 1 one other is widespread amongst Latinxs, no matter race or bodily look. It’s usually claimed that the tone of voice of the individual talking it reveals the intention of utilization, however simply because one thing is widespread doesn’t make it acceptable. […]