My thoughts about 2020:

Spring

On March 20, Governor J.B. Pritzker announced the Shelter in Place order for the state of Illinois. I assumed, to my relief, that I would stay home and prevent potential exposure to the deadly virus. My plan was to ride out the pandemic with the humble savings in my account. Surely, the government would get a handle on things and all would be back to normal by the time summer hit Chicago. To my horror, the Governor uttered an exemption for essential workers—triggering a series of excited phone calls from my employer. They were right to be excited for they predicted what I couldn’t see at the time: the pandemic was far from over and we were lucky to have a job.

I watched the news in disbelief as New Yorkers piled their dead into refrigerated trucks. As a refrigerated trucker, I struggle to imagine pallets of kale or bananas replaced by cold bodies. I wonder about things that only a refrigerated trucker would wonder about such as, what is the temperature set point for a reefer containing the dead? How many bodies fit in a truck before hitting the load weight capacity?

My route consists of delivering to four or five grocery stores and restaurants, which means I get my temperature checked four to five times daily. It’s why I know that my temperature ranges from 96.4 to 97.8 degrees throughout the day. Temperature checks along with hand sanitizer and masks are standard procedure. I wonder if conservatives mock me for wearing a mask even though my immune system may be compromised. I wonder if liberals mock me for lowering my mask even though maneuvering thousands of pounds on a pallet jack is dangerous when my glasses fog up. I’m doing the best that I can in the absence of a national strategy.

Unfortunately, the Trump administration was not alone in its failure to protect its citizens. Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) held massive rallies where he joined crowds of his supporters and kissed their babies on the cheek as if the death toll were not on the rise. Naturally, I worried about my elderly parents who live in a small apartment in Tijuana but spend several days a week at my sister’s house in California. My parents have two countries and two Presidents, but very little protection.

My parents are more worried about me. They have a point. It is often impossible to social distance inside high-risk environments like restaurants and grocery stores. Adding to my parents’ concern is the fact that the virus has been devastating for people with diabetes and other conditions like sleep apnea. I take two different diabetes pills and sleep with a CPAP machine. Without this regiment, my blood sugar spikes and I wake up gasping for air. I shudder when I speculate about the different ways the virus can affect my body.

Summer

In June, my dad was hospitalized due to complications from a surgery. I couldn’t visit him because of the risks that come with disease and air travel. I imagined getting infected with the virus and giving it to my dad only to make his condition worse. He is doing a lot better now, but it’s still too risky to visit. In August, my sister gave birth to her first child, a beautiful baby boy! I’m grateful for the cute pictures, but I wish I could hold him. I’ve missed so many family gatherings that I adopted two dogs just to have a family to come home to. As if a pandemic and homesickness weren’t enough, massive protests erupted.

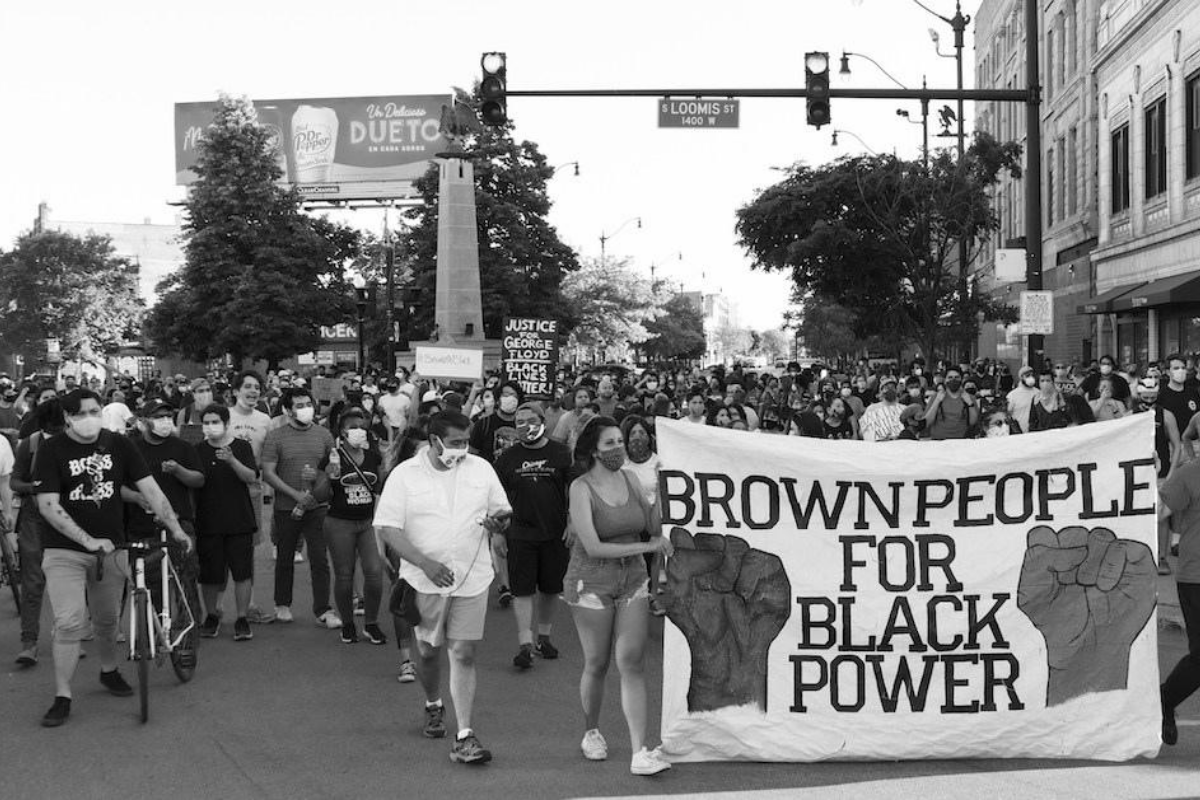

I watched as the Black Lives Matter movement took to the streets to protest white supremacy and demand the defunding of police. I watched Mayor Lori Lightfoot secure a perimeter to protect downtown businesses, while leaving neighborhoods exposed. I watched Black and Latinx activists in Pilsen, my neighborhood, lead unity marches after a few Latinx pendejos started attacking random Black Chicagoans in retaliation for looting. The operative word here is “watched,” for aside from donating a little money when I could, I mostly did nothing.

There’s these mental gymnastics I like to do when I think about my inaction. I’m adamant that my health is too compromised to protest. I remind myself that I served the movement in the past. Though military metaphors are frowned upon in social justice circles, I talk about myself the way veterans talk about serving in wars: I was there, I did it. I can back it up too. In 2006, I was arrested as part of a civil disobedience effort to unionize hotel workers in Los Angeles. At the time I worked for the Hilton, and we eventually won a union contract. Three years later, I got arrested again while organizing warehouse workers in Fontana. As a student at Whittier College, I organized the campus dining hall workers into a union. While other students were busy studying for finals in Wardman Library or pledging for one fraternity or another, I was leading worker delegations.

I was there, I did it.

Yet the pandemic has a way of exposing holes in a narrative. I was definitely there, but where am I now? The hotel industry has been hit hard by travel restrictions due to the virus. These are the very same workers I fought hard to organize. Additionally, what happened to the dining hall workers now that education moved online? I don’t know, but it can’t be good. It’s safe to say that organizers are still organizing and workers will continue to fight with or without me. They don’t need me so why the guilt? Perhaps it has something to do with risking my health for a paycheck, but not for the greater good.

Some have suggested that the work essential workers do is part of the greater good. There’s reason to agree with this sentiment. Farm workers are essential because most of our food is either grown or raised on a farm, but often overlooked is the role of the truck driver. Most Americans don’t live next to a farm and rely on grocery stores or restaurants for their food. The truck driver is the link between the farm and food on a table. As Americans pivot to grocery delivery services, reliance on drivers further increases. The work essential workers do contribute greatly to our communities so why do I hate it when we’re called heroes? It comes back to choice. Essential workers are not heroes who choose to sacrifice their health for their neighbors. It’s more accurate to frame essential workers as the neighbors we’re willing to sacrifice.

Fall/Winter

The main thing on my mind as the year ends is health. One of my dogs was diagnosed with a chronic condition. He suffers from tremendous thirst and consequently he urinates tremendously. He’s lost some muscle mass and develops sores across his body that ooze pus until they scab over. He’s resilient. He takes his medicine and never runs away from the vet. When I bathe him with medicated shampoo he sits patiently without a fuss. I whisper in his ear, “I love you.” It’s what he wants to hear. I know this because I too need to heal.

In October, I canceled the gym membership that I hadn’t used since March. There’s just too many bodily fluids and heavy breathing in a gym to feel safe. It’s getting cold in Chicago and I don’t have the mental toughness to exercise outside. The solution is a stationary bike. I’ve been using the bike a few days a week while listening to Prince and the Revolution. He starts with “Let’s Go Crazy” and by the time he sings “Purple Rain,” 42 minutes have passed. It’s fitting to conclude my workouts with a song about the end of the world in a year that feels like Armageddon.

Of course, various traditions around the globe believe the apocalypse brings an opportunity for rebirth.

A vaccine is promised next year and I sing, “I know times are changing, it’s time we all reach out for something new, that means you too.”

***

Arturo “Tootie” Alvarez is based in Chicago. He trucks. He writes. Not at the same time. Twitter @TootieAlvarez.