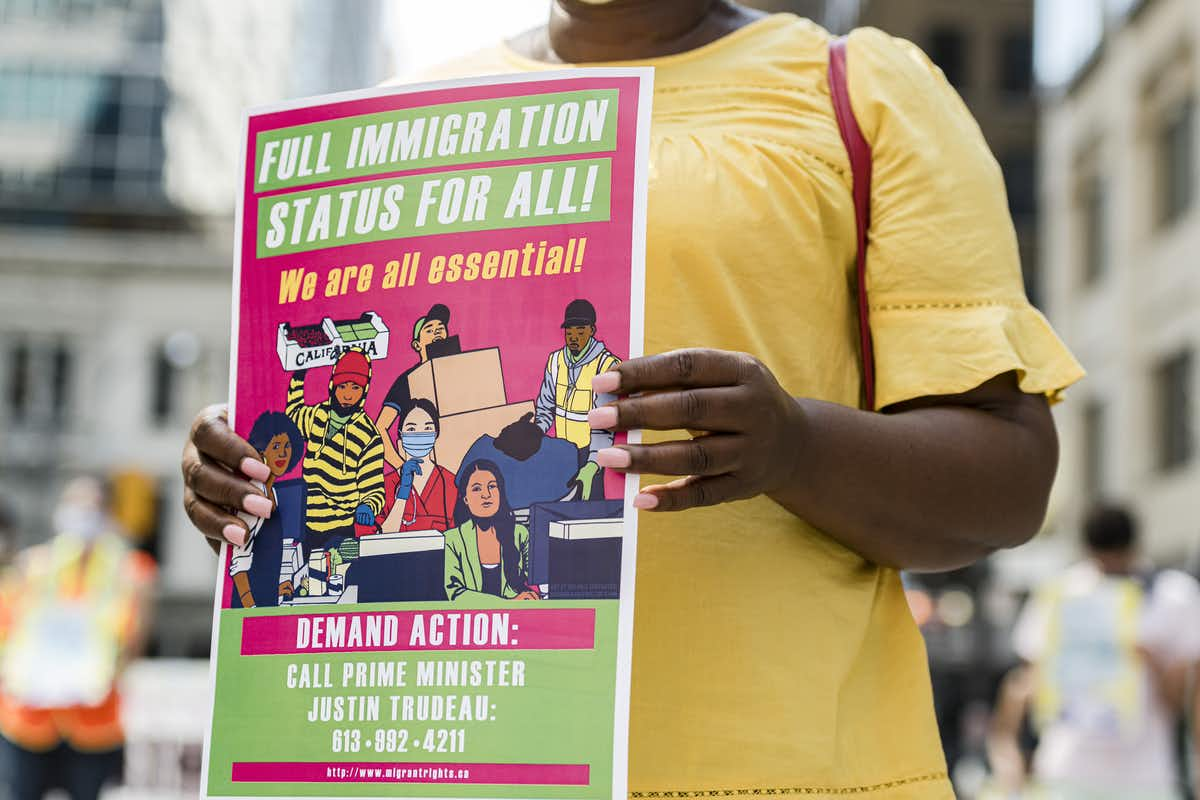

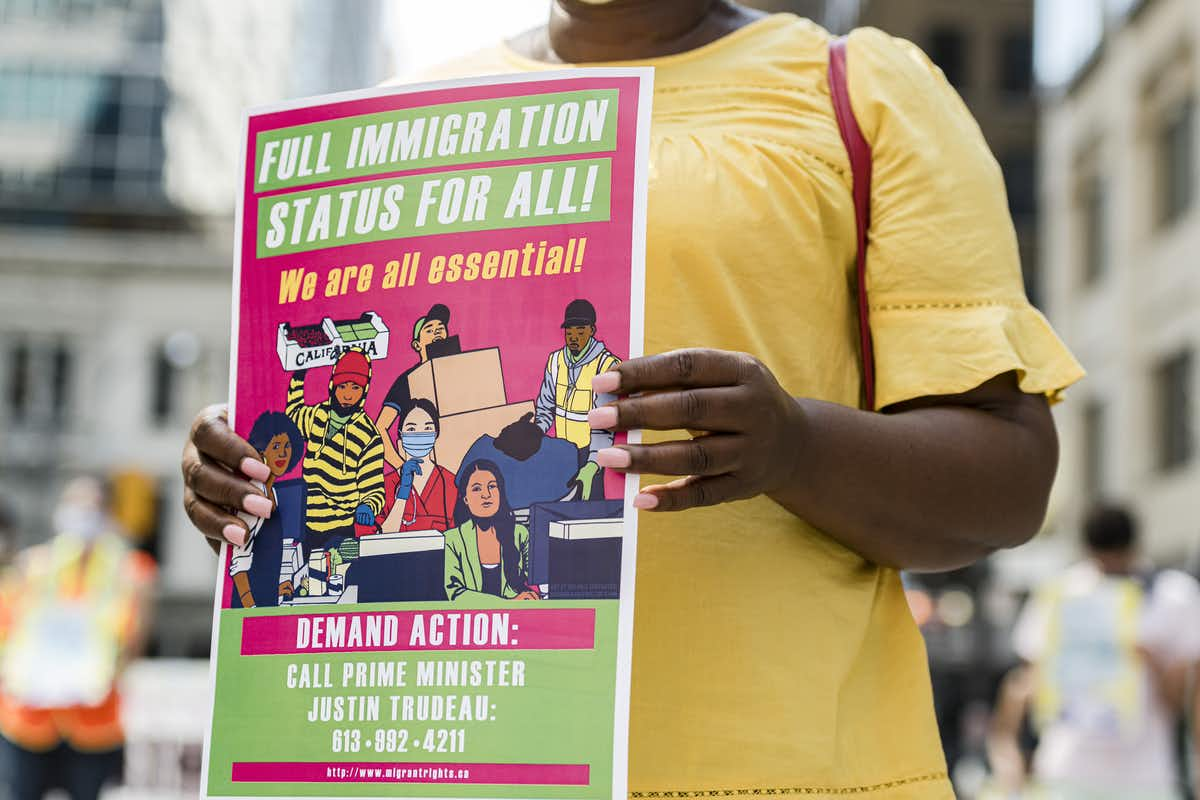

Temporary migrant workers in Canada are facing COVID-19 while dealing with an immigration system that leaves them vulnerable. (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Christopher Katsarov)

By Fay Faraday, York University, Canada

Migrant workers in Canada have suffered tremendously during COVID-19. Each year, some 85,000 low-wage migrant workers come to Canada under the Temporary Foreign Worker Program. They do essential work in many fields including health care, in-home care, agriculture, food processing, cleaning services, delivery services and construction. Thousands more are undocumented.

Just six weeks into the pandemic, documented complaints from over 1,100 migrant farm workers had already identified widespread wage theft, inadequate housing, lack of PPE, inadequate food, coercive restrictions on workers’ movement, intimidation, surveillance and heightened racism.

In 2020, 12 percent of migrant farmworkers —over 1,780 individuals— tested positive for COVID-19 in Ontario alone. Bonifacio Eugenio Romero, Rogelio Muñoz Santos and Juan López Chaparro from Mexico died of the disease.

Meanwhile, migrant workers providing in-home care for children, seniors and people with disabilities documented similar experiences, including overwork, loss of immigration status and a third of workers being denied the ability to leave their employer’s house at all since the start of the pandemic.

Low-wage migrant workers are restricted to working for a single employer, which creates the enormous power imbalance that facilitates workplace exploitation. Their ability to remain in Canada is dependent on maintaining their employer’s favor. Resisting exploitative workplace demands typically results in termination and loss of housing. In addition, these workers are subject to predatory recruitment fees and surveillance by recruiters, which pressures them to continue working even in abusive conditions to pay back recruiters.

Academic research, films and investigative journalism have recorded these conditions for decades with virtually no change.

Throughout the past year, migrant workers across the country rallied and demanded permanent status for all as the solution to their exploitation.

In a year of global protests about systemic racism, it is important to reflect on how institutionalized racism shaped Canada’s temporary labor migration programs and how migrant workers’ demands for #StatusForAll seek to correct that.

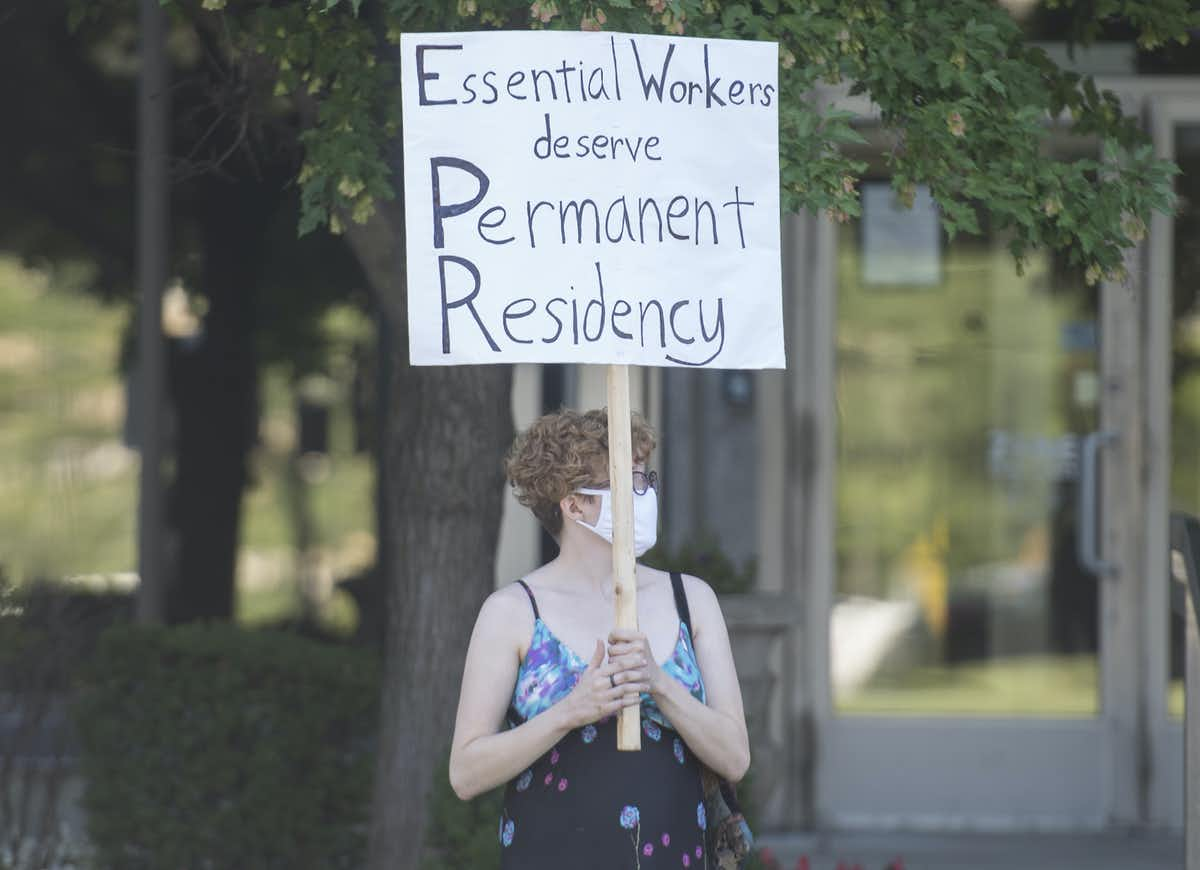

Migrant workers’ calls for #StatusForAll aim to end discriminatory immigration policies. (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Christopher Katsarov)

Racist Policies

Until the 1960s, Canada’s immigration laws imposed explicit restrictions based on racial hierarchies. Black and Brown people were barred from permanent immigration without special dispensation. Canada’s formal labor migration program for care workers was born in this era. Agreements with Jamaica and Barbados created the Caribbean Domestic Scheme in 1955.

From the late 19th century until the Second World War, Canada had primarily imported care workers from England and Scotland to live and work in employers’ homes. These women arrived in Canada with permanent status as British subjects. But as the economic options of white women expanded, Canada found it increasingly hard to recruit care workers from the U.K. and “non-preferred” countries in central and eastern Europe.

The Caribbean Domestic Scheme allowed a limited number of Black women to immigrate while being paid $150 less per month than their white peers. The women risked being deported if they were for any reason deemed “undesirable,” including if they left their employer. While this scheme ended a few years later, it set the template for later migrant care worker programs.

The Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program was created in 1966 in response to Ontario farmers demanding access to seasonal labor from the Caribbean as sources of imported labor from Europe became less available.

The policy rationale of both the Caribbean Domestic Scheme and the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program was to grant Canadian industries access to temporary migrant labor from the Caribbean while avoiding the increase of Black immigration to Canada.

The assistant deputy minister of citizenship and immigration summed up the government’s attitude in a memo dated January 13, 1965. He wrote that “by admitting West Indian workers on a seasonal basis, it might be possible to reduce greatly the pressure on Canada to accept unskilled workers from the West Indies as immigrants. Moreover, seasonal farmworkers would not have the privilege of sponsoring innumerable close relatives.”

Canada’s temporary labor migration programs have expanded in the decades since they were created. Yet the profile of workers doing the low-wage dangerous jobs is the same: overwhelmingly Black and Brown workers from the Global South.

Pathway to Permanent Residency

While Canada’s immigration system no longer explicitly restricts migration based on race, the reality remains that a points system for immigration continues to disproportionately exclude Black and racialized working-class workers from immigrating permanently to Canada.

While the federal government has created a pathway to residency for migrant healthcare workers, other essential workers have been excluded. (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Graham Hughes)

In August 2020. the federal government created a pathway to permanent residency for asylum claimants who worked on the frontlines of healthcare during the pandemic.

But this excludes many of the migrant and undocumented workers on the frontline whose labor was also lauded as “essential”—care workers, farmworkers, cleaners, workers who stock grocery shelves and do food delivery and more.

COVID-19 has laid bare the exploitation of migrant workers in this country. Exploitation that has intensified in pandemic conditions. Workers calling for #StatusForAll deserve a fairer single-tier immigration system that corrects the history of systemic racism.

***

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.