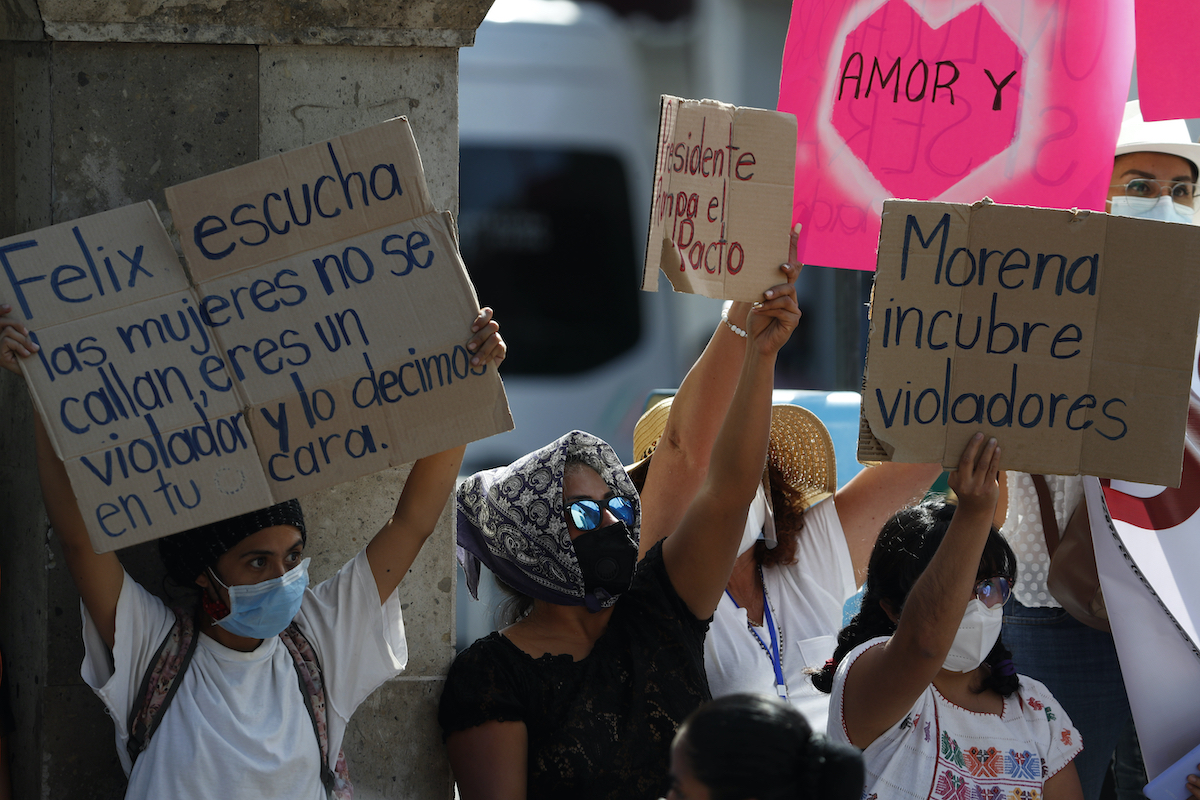

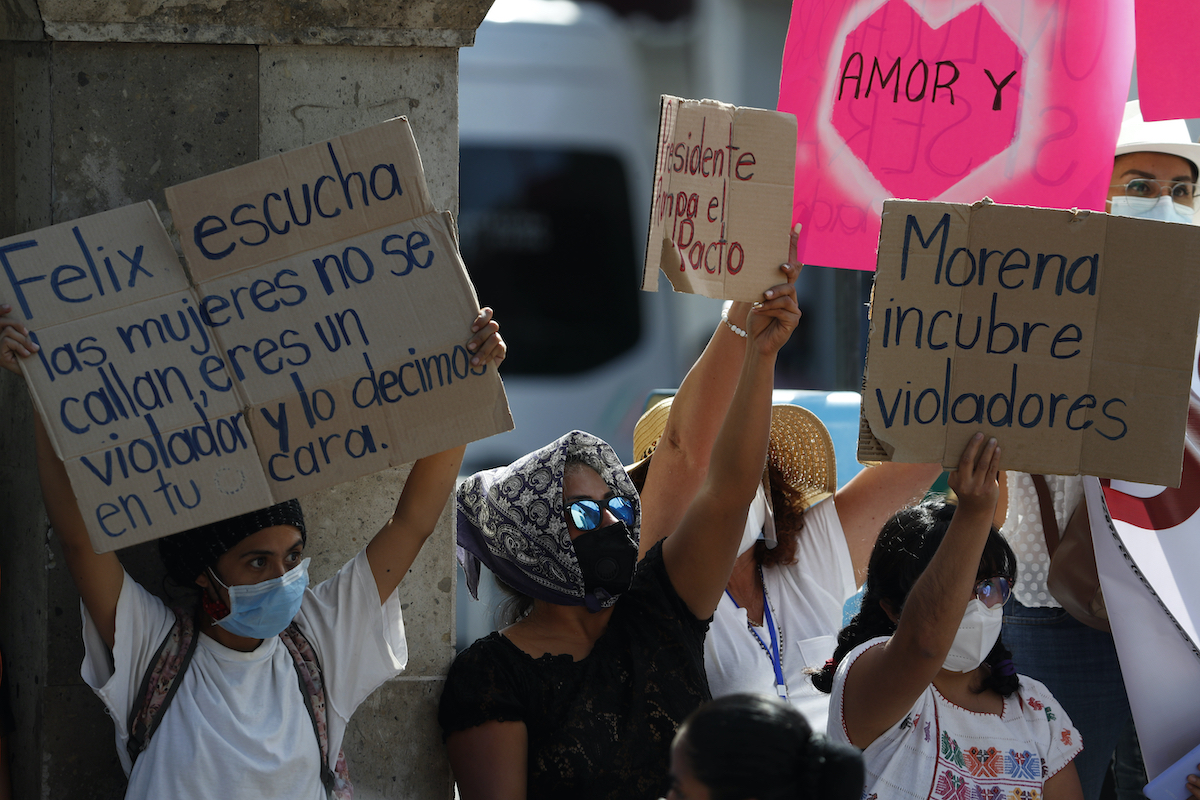

In this Feb. 24, 2021 file photo, women protest against ruling party politician Félix Salgado Macedonio during a visit by Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and Argentina’s President Alberto Fernández in Iguala, Mexico. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo, File)

By MARÍA VERZA, Associated Press

MEXICO CITY (AP) — Months of protests over the nomination of a man accused of rape, including open dissent within the Mexico President Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s party, haven’t derailed the selection of his preferred candidate to be governor of the Pacific coast state of Guerrero.

Félix Salgado Macedonio’s campaign could become secondary to López Obrador’s costly decision to continue backing an ally accused at least twice of sexual assault.

Salgado has dismissed the allegations as lies, the president has minimized them as political attacks and late Thursday, state election officials confirmed Salgado as the party’s candidate for the June 6 election.

But the controversy has deepened the disillusion and mistrust among women toward López Obrador, who has vowed to be a champion of women’s rights, and opened fissures within his own National Renovation Movement party, known as Morena.

“There is going to be significant erosion that’s not limited to Guerrero,” said Lorena Villavicencio, a federal lawmaker from Morena who has been outspoken in her opposition to Salgado. “It is going to have an impact in many cities across the country.”

Guerrero election officials ruled that since Salgado hadn’t been convicted of a crime, the decision on his candidacy was up to the party.

The Guerrero vote is part of nationwide midterm elections that are seen as critical for López Obrador’s desire to transform Mexico. In addition to 15 governorships, voters will determine whether the president’s allies maintain control of the lower chamber of Mexico’s Congress.

Salgado can only be removed as a candidate if he steps aside or if the party strips him of his political rights. But that appears improbable, even in a leftist party focused on López Obrador, who won power in 2018 with a promise to be Mexico’s first egalitarian administration.

“Morena can’t be a party where electoral pragmatism beats out its principles,” Villavicencio said.

In this February 15, 2021 file photo, the Spanish-language graffiti message “AMLO is complicit” is written on the ground outside the National Palace, as a women’s collective protests against support by the ruling Morena party. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell, File)

Even before Salgado’s candidacy, feminist groups had grown suspicious of López Obrador, who had seemed to wave off growing protests over gender-based violence and the government’s lack of a response.

Basilia Castañeda, a grassroots Morena activist and a party founder in Guerrero, came forward late last year to say that Salgado raped her when she was 17. For two decades she had remained silent, fearing the popular politician who had been a senator, deputy and mayor of the Pacific resort city of Acapulco.

The state prosecutor’s office said that too much time had passed since the alleged crime in 1998, but Castañeda’s lawyers are considering an appeal, arguing that courts should account for the fact she was a minor and she was scared to speak out against a powerful politician.

Castañeda and her family say they have been threatened and have requested government protection.

López Obrador has insisted on the presumption of innocence for Salgado. He has noted that Salgado was chosen by a party poll and said the people can’t be wrong. The controversy, he says, has been fanned by the conservative opposition and enemies of his administration.

But an earlier sexual assault allegation against Salgado has stalled under an opposition party that now governs Guerrero. Xavier Olea, Guerrero’s attorney general from 2015 to 2018, said that current Gov. Héctor Astudillo had “strictly prohibited” investigating Salgado. Astudillo has denied that allegation, and prosecutors said this week that an allegation of sexual assault against Salgado remains officially under review.

The woman in that case worked for Salgado when he ran a local newspaper. In her complaint to the state prosecutor’s office in December 2016, obtained by The Associated Press, she alleged being raped, abused and drugged. The AP is not identifying her, because she has not publicized her case.

Since January, the controversy has divided Morena. While the party’s executive committee has echoed López Obrador’s defense of Salgado, top female members, including Secretary General Citlalli Hernández, have demanded an end to his candidacy.

“We feel very indignant,” Villavicencio, the federal lawmaker. She said Morena was based on the principle of ending “the untouchables, the corruption and the impunity.”

Morena’s National Committee on Honesty and Justice appeared to try to resolve the issue in February by calling for another internal poll on a candidate, but it also affirmed that the accusations against Salgado were “unfair and unfounded.”

The results of the second poll are expected next week.

In this February 24, 2021 file photo, a woman who has been injured during a scuffle with supporters of local ruling party politician Félix Salgado Macedonio is helped by a fellow demonstrator during a visit by Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and Argentina’s President Alberto Fernández in Iguala, Mexico. (AP Photo/Eduardo Verdugo, File)

Olamendi, Castañeda’s lawyer, said Morena’s internal processes were “a farce.”

“It is the worst message we could send women, that if you break the silence, this is what can happen to you,” she said. She blamed many Morena politicians who have stood with the president rather than try to convince him that the support for Salgado was an error.

Claudia Clavín, a member of a network of female political scientists, #NosinMujeres —“Not without Women”— said that for many Morena members, loyalty to López Obrador has outweighed their commitment to women.

Villavicencio has been one of the exceptions. She said she’s committed to working within Morena “so that all the men in all public spaces understand what equality implies… and the responsibility you have from a public position to guarantee that right.”

Meanwhile, the controversy has continued to build ahead of marches planned across Mexico on International Women’s Day, Monday.

“The feminist protests are going to become more radical,” said Clavín. “Now they’re not the only indignant ones, but also other parts of society.”