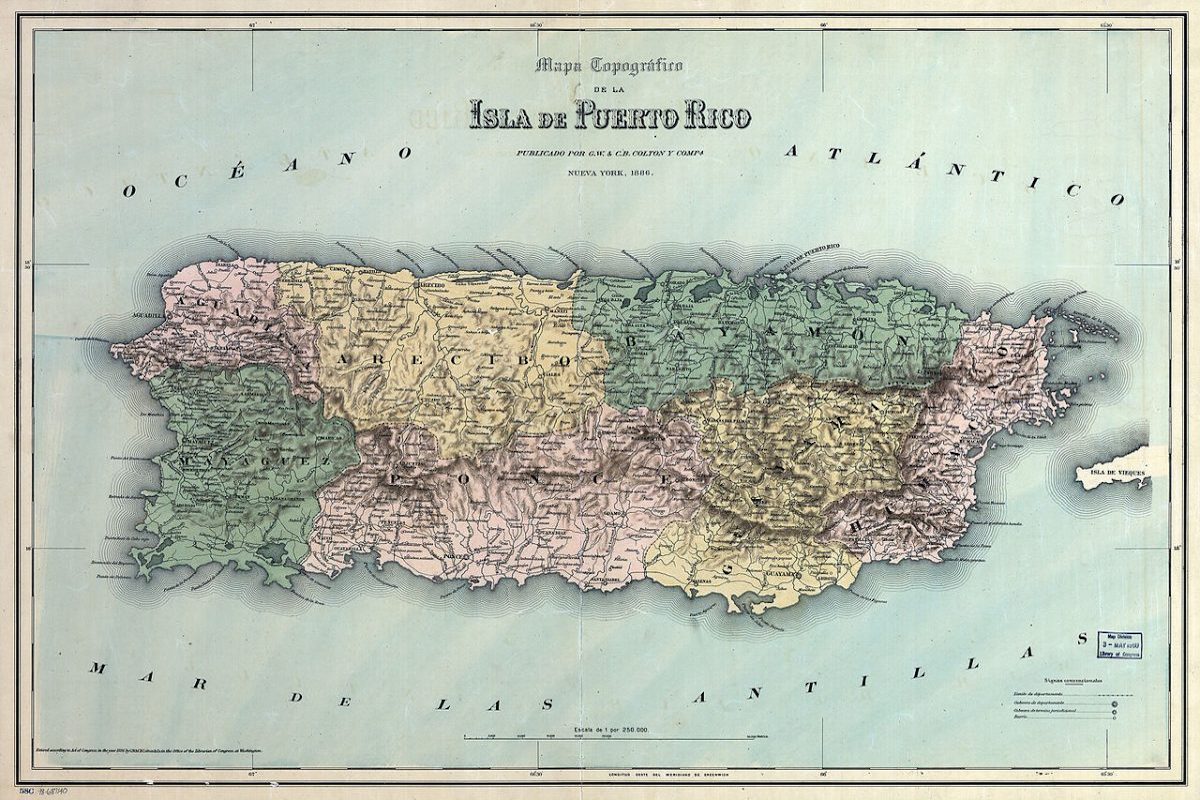

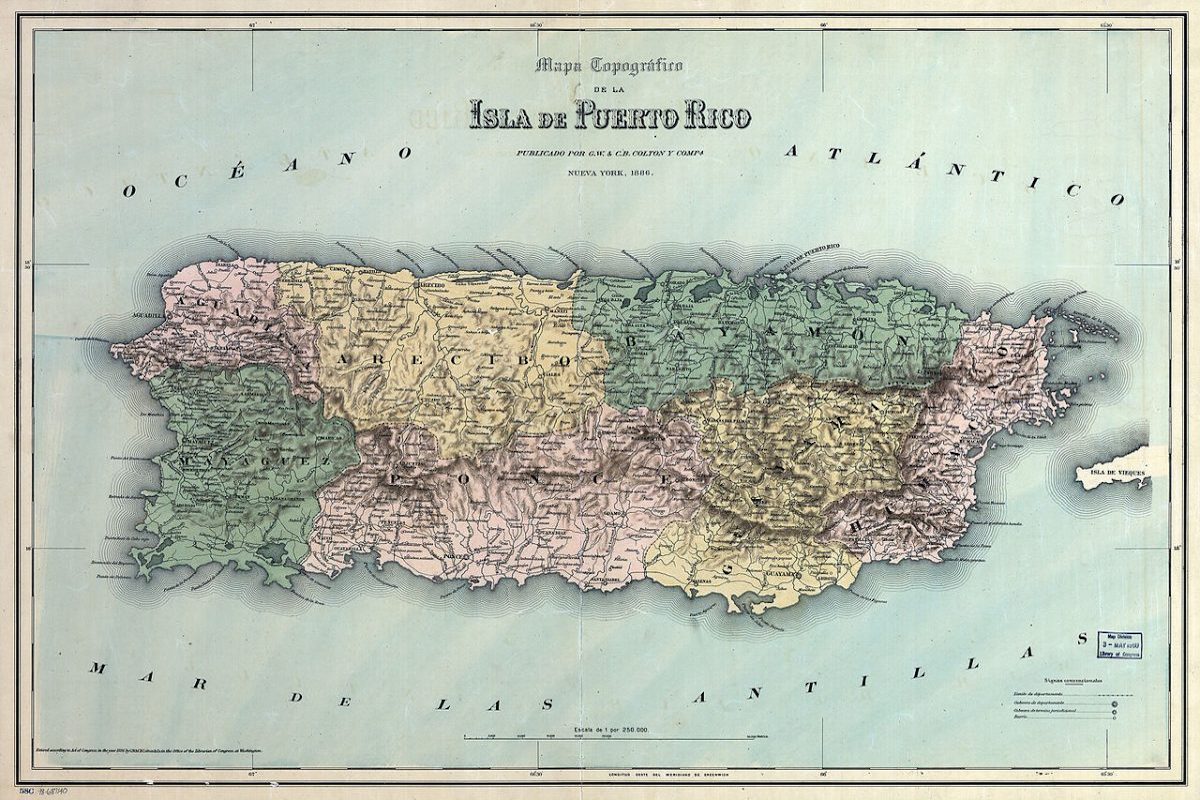

(Public Domain)

“[He] fought for the independence and freedom of his people and his country, died terribly for his efforts at a very young age, and is somebody probably not well known in history outside of [his homeland].”—Cameron Reilly, host of a history podcast

LAS VEGAS — The above quote could’ve been said about a lot of people, especially in Latin America. Che, of course. Sandino. Martí even. Or Don Pedro, if you forget the “young” part.

It was said of Wolfe Tone.

Few people know the name Wolfe Tone (his first name was Theobald, but he’s remembered simply, if at all, as Wolfe Tone). On the handful of times I’ve uttered his name in conversation, I always get a confused look. Most people couldn’t tell you if Wolfe Tone was a person, place or thing.

You could say he’s all three.

Wolfe Tone was a man, a revolutionary, co-founder of the United Irishmen, who fought to see Ireland break free of England and monarchy, and form an independent republic à la the United States.

For that, Wolfe Tone is Ireland. Just like Che is Cuba, Sandino is Nicaragua, and Don Pedro is Puerto Rico, whether their names are celebrated there or not, or even remembered. Except for Che, who fought and died trying to free the whole world from an inhuman economic system, they all fought to free their homelands, and paid the greatest price.

“Many suffer,” Wolfe Tone wrote, “so that some day all Irish people may know justice and peace.”

As a lover of justice and peace, Wolfe Tone is the idea not only of Irish independence, but of independence itself.

Portrait of Wolfe Tone (Public Domain)

I discovered him in college, in an Irish history course. There were some 10 kids in the class —and by “kids” I mean 20- and 30-somethings— and three or four were grad students. I had to be the only non-white person in the class. I was the only dark one, anyway.

The course roughly covered the period from the early Jacobite rebellions to the Irish War for Independence, and, suffice it to say, we talked a lot about freedom fighting. The other kids in the class, even the young associate professor himself, had a strange, detached way of speaking about these struggles for freedom and independence. So much emphasis was placed on learning the dates and locations of battles, and the names of the leading figures —the people, places and things of history— that the actual essence of the story got shoved into the background.

We were studying Ireland’s struggle to gain its independence from England, or at least secure a little autonomy —and even defend, at times, its very right to exist— yet my classmates acted as if it were all purely academic, like the simple exercises assigned to second-graders. We all agreed that what the English Crown and its Parliament did to the Irish people was heinous, treating them like subhuman scum in their own land. But my classmates seemed to view the question of Irish independence as more or less arbitrary.

Independence? Sure, why not.

But I was never on the fence about any of it.

I was fresh from taking a course on Puerto Rican history, taught by Prof. José López, younger brother of Oscar López, the Puerto Rican revolutionary who at the time was still where he’d been since the ’80s—in prison. For Prof. López, freedom and independence were beyond academic or arbitrary. They were matters of life and death, of the right not to be someone’s property.

By the time I took his class at UIC, Prof. López had already spent decades pushing for Puerto Rican independence, and for Puerto Rican empowerment in the United States—the right of Puerto Ricans not to be treated as a colonized people both there and here. Even after all the time and energy he’d poured into those twin causes, you could see the fire in him still. If anything, it burned more.

When he spoke of Betances, and especially Don Pedro, his tone weighed down by the sheer reverence with which he regarded them, we were made to believe that these names didn’t refer to mere mortals. These were titans, semi-divine heroes, Perseus reborn, with a supreme intelligence and righteousness only matched by their moral courage. They were Boudica. They were Túpac Amaru, both the original and his descendant.

They were Puerto Rico. Their names stood for freedom.

When we got to Wolfe Tone in that Irish class, I immediately recognized another Betances, another Don Pedro. Another Che. Another Martí.

Just like them, Wolfe Tone was born of privilege but hated aristocracy and sided with the underclass—when he toured America in 1795, he thought the elitism based on money here was just as bad as the elitism based on birthright back home. Raised a Protestant, he began his career advocating for the rights of Catholics.

Maybe because I’m a Puerto Rican, or a Honduran, or just a hater of religion and a lover of humanity, but his writing sprayed gas on the flames already blazing within me:

“To subvert the tyranny of our execrable government, to break the connection with England, the never-failing source of all our political evils, and to assert the independence of my country, these were my objects. To unite the whole people of Ireland, to abolish the memory of past dissensions, and to substitute the common name of Irishman, in place of the denominations of Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter, these were my means.”

And maybe it’s because I’m a Black Latino man from an immigrant working-class family, a former have-not of the highest order, a riff-raff radical, that Wolfe Tone’s words washed over me like gospel:

“Our independence must be had at all hazards. If the men of property will not support us, they must fall; we can support ourselves by the aid of that numerous and respectable class of the community, the men of no property.” (emphasis his)

The man was no saint, though—no hero ever is. Early on, as a wide-eyed and ambitious young man looking to succeed within the system, Wolfe Tone wanted the British to establish a military colony in Hawai’i. That fact alone would make a lesser man damn near irredeemable in my eyes. Then again, Jefferson was a sexist slaveowner, which hasn’t stopped people of all genders and colors from deploying his words in their calls for freedom and justice, from Dr. King to A.O.C.

History is like life, messy as fuck. But we don’t scrap either just cuz things get messy. C’est la history!

Wolfe Tone led the failed rebellion of 1798. The British celebrated their victory over the rebels with massacres and rapes, butchering tens of thousands of Irishmen and women. They caught Wolfe Tone’s brother Matthew, gave him a quickie trial, and hung him.

When they caught Wolfe Tone, he was wearing the uniform of a French officer, which he technically was. “I entered into the service of the French Republic with the sole view of being useful to my country,” he said at his trial:

“To contend against British Tyranny, I have braved the fatigues and terrors of the field of battle; I have sacrificed my comfort, have courted poverty, have left my wife unprotected, and my children without a father. After all I have done for a sacred cause, death is no sacrifice. In such enterprises, everything depends on success: Washington succeeded—Kosciusko failed. I know my fate, but I neither ask for pardon nor do I complain. I admit openly all I have said, written, and done, and am prepared to meet the consequences. As, however, I occupy a high grade in the French army, I would request that the court, if they can, grant me the favour that I may die the death of a soldier.”

He asked to be shot as a soldier instead of hanged like a common criminal. The request was denied. So he tried slitting his own throat in his cell, supposedly, though some say he was shot in the neck. Whatever it was didn’t kill him. The doctor who patched him up told him not to speak or he would bleed to death, which Wolfe Tone considered good news.

He died in November 1798, only 35 years old.

He was young and died fighting, like Che and Martí. And like them, he was an intellectual who really had no business being anywhere near a battlefield, much less commanding soldiers. But he was as Che described himself in his last letter to his parents: “one who risks his skin to prove his truths.”

Wolfe Tone. Betances. Martí. Don Pedro. Che.

These men were powerful thinkers and godlike with words, hurling phrases like thunderbolts. Their booming broadsides will resonate forever.

Last week was St. Patrick’s Day, and thinking of Ireland always makes me think of Puerto Rico, two islands with vibrant cultures dominated by WASPy foreign powers that have tried hard to snuff those cultures out, along with the people. The Great Famine, the most devastating moment in Irish history, wasn’t really caused by a potato blight, but by the British policy of exporting food out of Ireland even as over a million Irish people died of starvation, with another million leaving the island. Any Puerto Rican or Hawaiian, any colonized people for that matter, knows exactly what the British Crown intended: it wanted to depopulate the island, out of a desire to make the population more controllable, but also out of a pure hatred for the natives.

Same goes for Puerto Rico, or Hawaii, whose people aren’t poor because they’re lazy and can’t manage their own economies. They’re poor because their economies are controlled by a foreign power that doesn’t care about their health or prosperity, only its own. Empires always work this way.

In September 2017, Puerto Rico was hit by two Category 5 hurricanes in the span of two weeks. The second, María, was the biggest storm in the world that year, and the worst to hit Puerto Rico in over a century. Thousands of Puerto Ricans died, and millions more were left without power and drinking water for months afterward.

Yet the U.S. government, the richest and most powerful the world has ever seen —just as Britain’s was during the Famine— not only looked on from a distance, but kept extracting, awarding wasteful contracts to shady companies and pressing Puerto Rico to pay the massive debt it had incurred under the economic policies imposed by the same U.S. government. Sound estimates say that Puerto Rico’s debt is equal to all the money it has lost through the Jones Act, a colonial law that requires any and all goods shipped into and out of Puerto Rico be carried on U.S.- owned and operated vessels, which makes every recovery effort in Puerto Rico that much harder.

Puerto Rico has one arm tied behind its back, and Uncle Sam’s hand in its pocket. The relationship between Ireland and John Bull had been that way for centuries, and the free and independent state of Ireland is still bullied by its former master today. Northern Ireland remains part of the United Kingdom, and is one of the world’s powder kegs. The potential for violence in Northern Ireland, or anywhere that self-government is denied, can be explained by the popular protest chant: No justice, no peace.

St. Patrick is remembered as the Roman missionary who came to Ireland and got rid of all the snakes. The story is meant to be taken as an allegory for the Christianization of Ireland, since there were no snakes on the island, but there were plenty of druids and other pagan Celts.

Puerto Rico needs its own St. Patrick to get rid of its snakes, and I don’t mean the corredora. I mean the infamous vendepatria, those slimier, more venomous snakes with forked tongues who would sell the health and freedom of the Puerto Rican people for a little green and a nest egg. Those faithless heathens who don’t know if Puerto Rico should cling to its master, or assert its freedom and independence, as is the right of every human being.

Puerto Rico needs its own Wolfe Tone. It needs another Don Pedro.

But how many will it take to free Puerto Rico?

***

Hector Luis Alamo is the Editor and Publisher of ENCLAVE and host of the Latin[ish] podcast. He tweets from @HectorLuisAlamo.

I fully understand Mr. Alamo’s longing for a liberating hero that will free Puerto Rico from the unfair treatment of 123 years by the U.S. political-economic power structure. However, under both domestic and international law there are two ways, not one, out of that conundrum: separate Puerto Rican sovereignty in the global community of independent nation-states or SHARED Puerto Rican sovereignty WITHIN the Union of political entities that is the United States of America. Most of those of us who actually live in Puerto Rico have concluded that however enticing independence looks on paper it presents a huge number of difficulties on a practical level, not least of which is the uncertain fate of the U.S. citizenship that 6 million Puerto Ricans in the U.S. mainland and a further 3.2 million in the Caribbean U.S. territory have come to appreciate, cherish and, yes, even love, because we understand perfectly well, like our Afro-American brothers and sisters did before us, that one shouldn’t confuse the abuses committed against Puerto Rico by the U.S. power structure with the U.S. itself, much less with the promise of full rights for all American citizens inherent in the U.S. Constitution and U.S. laws. Yes, we treasure our ethnicity and culture but we’re equally appreciative of our legal-political condition as U.S. citizens because they’re not incompatible in the least. No doubt the “half in, half out” compromise that is Puerto Rico’s commonwealth status with regard to the U.S. at large has outlived its usefulness and must come to an end as soon as possible but I respectfully submit that Puerto Rico would actually be MORE VULNERABLE, not less, to future U.S. economic pressure and trade abuses as an independent republic than as a State of the Union. No offense but I much prefer to have Florida as a template for a future Puerto Rico than the Dominican Republic. Idealism has its place and liberating heroes are fine and dandy–in the pages of history books. In my opinion –presently shared by a majority in Puerto Rico– the PROPER way to redress past U.S. grievances against our people is by granting Puerto Rico statehood, NOT independence.