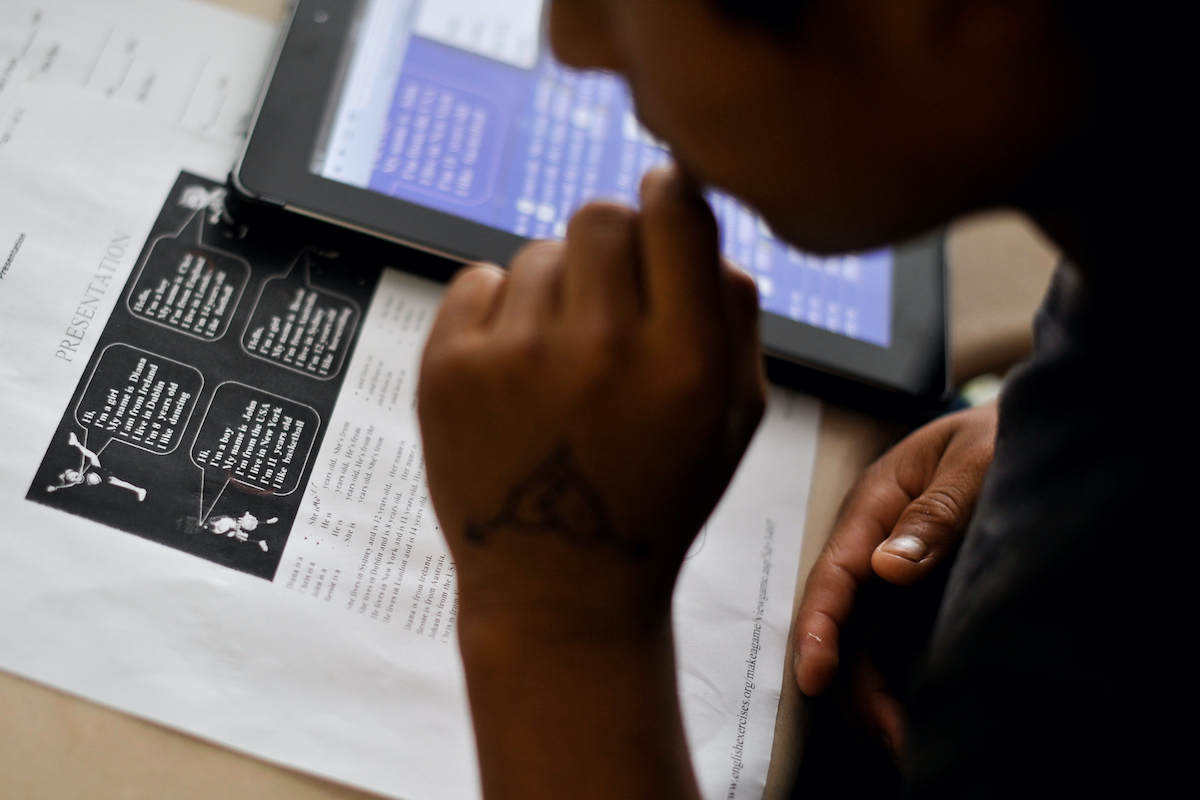

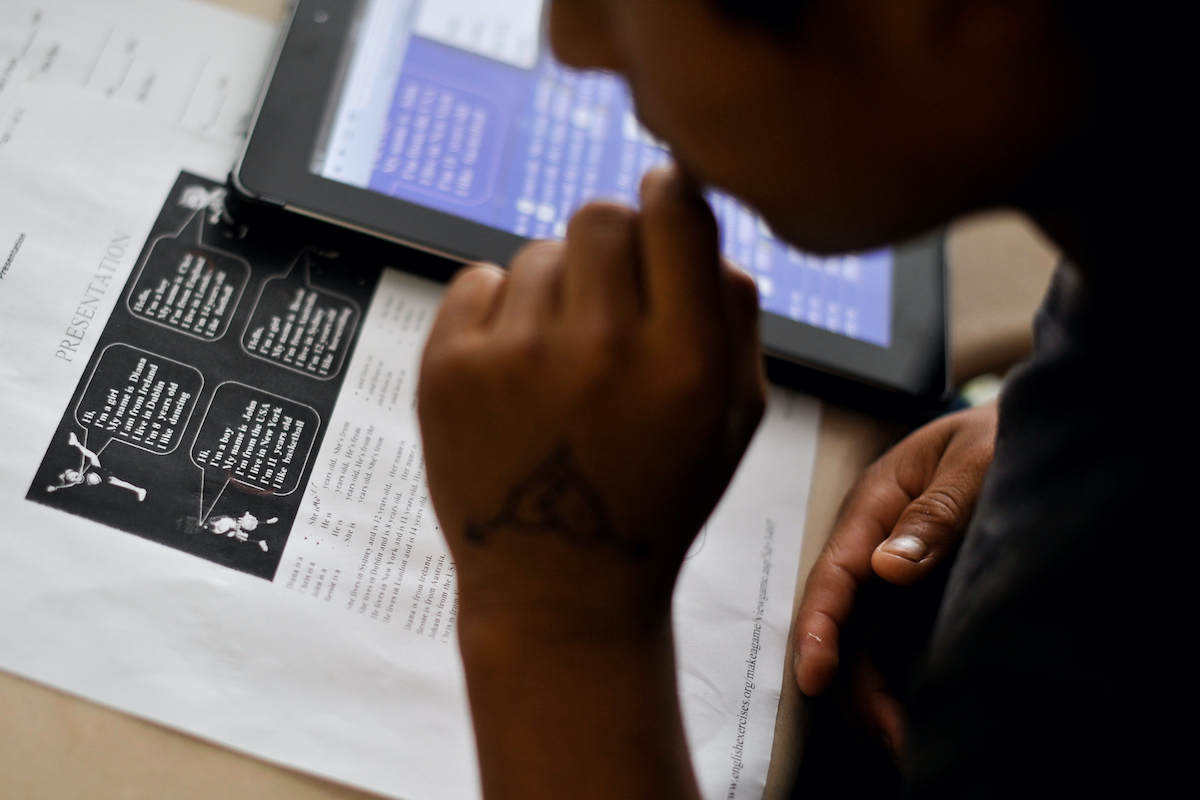

(AP Photo/Emily Varisco)

By Cecilia Silva

The popular Netflix series, “Ginny and Georgia” focuses on the story of a young Black teen as she navigates the world of suburbia while balancing multiple identities.

While this on-screen story has been hugely successful, other TV series have been wildly sensitive and highly criticized such as “Black-ish,” “Dear White People,” and the updated “One Day at a Time.”

All of these shows do one important job that is long overdue. They force viewers to face the reality that students of color have experienced many unique obstacles while going through the public-school systems in suburban neighborhoods.

These obstacles can range from racist remarks from classmates and teachers to curriculum and policies that only highlight the importance of white narratives and history. But one of the most harmful obstacles is the incorrect labeling of immigrants and students of color as English Second Language (ESL) or English Language Learners (ELL).

This labeling of students as “others” who are not white does not represent the reality of the shifting numbers of those who do comprise the middle class. In the past several decades, there has been an increase in racial diversity amongst the middle class. People of color have worked hard to establish themselves in suburban areas that provide better opportunities for their children.

To understand the problem, it is important to understand what it means to be “middle class.” The Pew Research Center has stated that middle class and middle income have become interchangeable over the past several years, so that your income defines what class you are in. In 2014, the medium income for a family of three in the middle class was $73,392.

According to The Brookings Institution, the middle class is no longer exclusively made up of white Americans, but instead has become far more diverse over the past four decades.

In 1979, white Americans made up over 84% of the middle class, but in 2019 that number had significantly dropped by 25%. More specifically, Black Americans account for 12%, Latinx Americans account for 18%, and Asian, American Indian, Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, biracial Americans account for the remaining 10% of the middle class.

In “Ginny and Georgia,” Ginny, who was often the only Black girl in her mostly white classroom, quickly brought back memories of my own experiences as a Latina attending school in a predominantly white suburban school district, Klein ISD of Spring, Texas in the 2000s.

Understanding this show is fiction, when her peers and the adults who were supposed to support her when she was singled out for her identity and instead didn’t, I wondered why this problem continues to exist.

If suburbia and the middle class are becoming more diverse, then why has the public school system not made an effort to prioritize the importance of readjusting their school policies to become more inclusive and culturally sensitive?

One solution is bringing Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion initiatives to school boards that would encourage them to reevaluate the curriculum and policies that harm students and disrupt their educational experience.

The United States Department of Education has publicly stated that diversity and opportunity are key to the success of a growing nation. On the DOE website, the first line states “a growing body of research shows that diversity in schools and communities can be a powerful lever leading to positive outcomes in school and in life.”

The text mentions the need to invest in innovation, expanding opportunities, and opening doors. But ESL/ELL courses are not opening doors with the standard practice that is in place today, and they haven’t for a long time. This critical discussion around the need for more DEI in the public school system is urgent.

The earliest case of ESL practices in Texas is most popular due to the 1949 case of Hernandez v. Driscoll CISD. Linda Pérez was one of the many students who was placed in “Mexican” first grade to learn English, despite the fact that she only spoke English.

She and many other students were forced to undergo a three-year program of the first grade which in return set these children apart from their peers. This is one of the earliest and most known cases that set the tone for ESL/ELL practices, but it still happening today. Students of color are disproportionately affected by these discriminatory practices and policies.

While the ESL population is estimated to be nearly 5 million students K-12 in U.S. public schools, not all of them need to be labeled ESL and removed from their classrooms for a separate track. Instead, we should explore following the path that some institutions are already taking, such as Brentwood Schools in Los Angeles.

In 2020, Brentwood Schools, a private K-12 institution, shared the start of their multi-year DEI strategic plan. They’ve outlined community forums, surveys of students, staff, parents/guardians and alumni experiences; dialogue sessions; a curriculum review; and DEI consulting. Sensitive, inclusive curriculum and training for teachers and administrators would reveal the damaging rush to judgment currently in place for ESL/ELL practices and provide the opportunity to learn where improvement is needed.

When done well, DEI initiatives provide the opportunity for students of color to succeed in an environment where they would feel welcomed and wanted. They also allow for predominantly white students and communities to become more culturally aware and sensitive, which in return will better prepare them for the diverse society that they will enter after graduation.

As a Latina attending a predominantly white school district, I was removed from my classes and identified as an ESL/ELL student.

This led to my placement in courses where I began learning material I already knew and was simply the result of my being a shy second-grader. None of the faculty or staff asked my parents about our home practices or if we even spoke another language at home.

My parents have attended school in the U.S. since they were children. English was and still is the predominant language we speak at home. My mother was furious when she learned I was not receiving an adequate education.

Checking a box doesn’t give context to a student’s knowledge of a language and/or their intelligence. My family simply identified our ethnicity as “Hispanic/Latino,” which in return meant we were “less than.”

Klein ISD’s direct labeling of my family as “other” set the tone for my educational experience. In return, I was bullied because of my heritage and physical appearance throughout the entirety of my attendance.

When my bullying was brought to the attention of the administration, my family was told there was “no proof” despite the notes that strictly told me to end my life and that I could be “making it up for attention.” The issue wasn’t resolved until I was told the only remaining opportunity was to graduate early with an adjusted degree plan.

No child should have to decide between their education and their mental well-being.

Children are resilient, but it isn’t their responsibility to grow from every trauma that a system out of their control imposes on them—it’s everyone’s responsibility to protect children, their education, and their innocence.

By implementing policies that would re-evaluate the discriminatory practices that currently exist, no child would be left behind and locked out of opportunities as I was.

However a student identifies their educational future would be brighter.

***

Cecilia Silva is the Texas Program Manager for ReflectUS, a Majority Leader with Supermajority Education Fund, and a 2021 Public Voices Fellow of The OpEd Project.

So in 25 years the largest minority group will be Asians. so maybe we should teach Mandarin in schools? That will be the language to learn. Also. Maybe parents can learn the language and help to teach their children. Bec obvi we can’t teach 30 diff languages in our elementary schools. Too expensive and not enough people contributing their fair share.