A San Salvador COVID-19 cemetery which buried 20 people a day in July 2020. Many experts viewed official fatality totals as undercounts. (Photo: Carlos Barrera/El Faro)

Welcome to El Faro English.

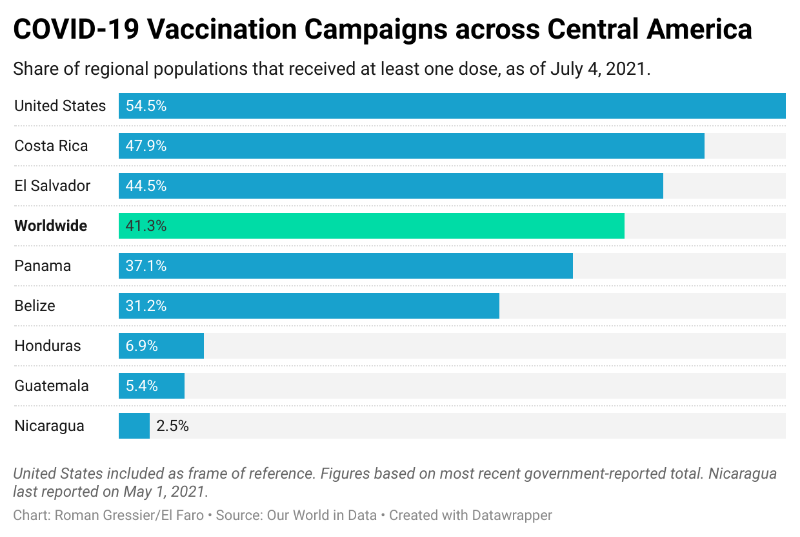

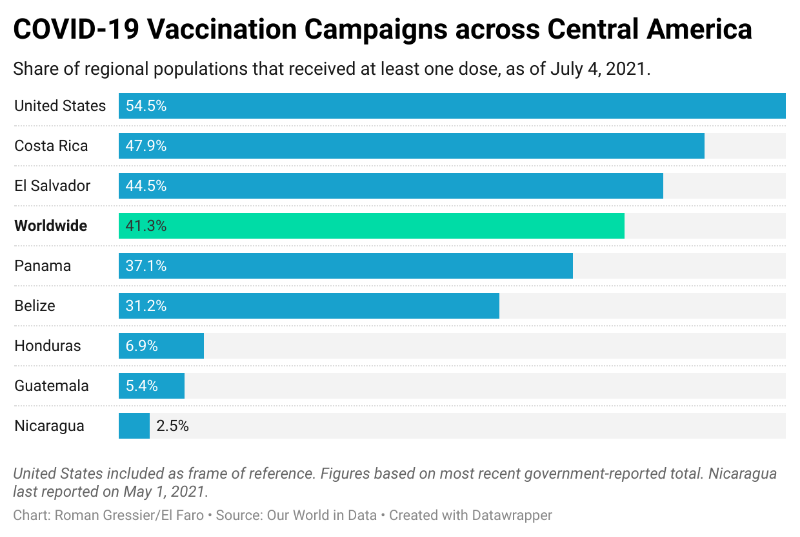

Sixteen months into the pandemic and five months since pharmaceutical giants began pumping out vaccines, Central America remains vastly undervaccinated. Limited access to shots in the region, however, seems to be conditioned on more than simply need and availability.

After contributing to the spread of COVID-19 in Central America through deportations, the United States is now attempting to, at least partially, contain its spread in Central America through vaccines. The Biden-Harris administration recently announced a major round of vaccine donations to Central American countries, which so far have mainly relied on shots from China and Russia.

On Friday, the U.S. embassy in El Salvador announced the arrival of 1.5 million doses of the Moderna vaccine. Just hours later, the Chinese Embassy announced it would send 1.5 million Sinovac vaccines to El Salvador. The back-to-back vaccine donations landed in El Salvador as the United States and China —the latter of whose diplomatic footprint is growing in the region— jockey for leverage with the Bukele administration.

Across El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala, there have been more than 650,000 confirmed COVID-19 cases and nearly 19,000 reported deaths—with weak health systems struggling to respond to the ongoing scourge.

When the State Department pulled the visas of four senior Bukele officials last week for corruption or undermining democratic institutions, Health Minister Francisco Alabí’s name was conspicuously absent from the list—this despite evidence that he favored family members with pandemic-related contracts, as well as the fact that prosecutors raided his ministry in November as part of an investigation into millions of dollars of illicit pandemic spending.

Sanctioning Minister Alabí or other ministry officials in the report to Congress would mean, by law, reconsidering ongoing cooperation with the ministry in charge of vaccine rollout.

China has taken a different tack in vaccine diplomacy, donating two million doses in March and April while Bukele sparred online with members of the U.S. Congress over allegations of corruption and authoritarianism. In the wake of the May 1 legislative coup, the Chinese embassy emphasized its commitment to the principle of non-interference in a tweet, saying it believes “the Salvadoran people are capable and wise enough to handle their own internal affairs.”

The Chinese Embassy, meanwhile, has struck a different tone: "China always applies the principle of non-interference in the internal affairs of others and is convinced the Salvadoran people are capable and wise enough to handle their own internal affairs." https://t.co/F6903qG1xX

— El Faro English (@ElFaroEnglish) May 3, 2021

The Salvadoran government’s ability to amass vaccines from abroad —while also sealing off the details of these contracts and its broader vaccination strategy through 2024— has been a major boon for its regional image.

While the governments of Honduras, Guatemala, and Nicaragua scrounge to get needles into the arms of 10 percent of their populations, about 44 percent of the total population in El Salvador have received at least one dose. On Saturday, Bukele announced that anyone over the age of 25 is eligible for a vaccine and that the country will pick up the pace by vaccinating 75,000 people per day.

3 buenas noticias en 15 minutos…

— Nayib Bukele ?? (@nayibbukele) July 3, 2021

The Salvadoran government has gone as far as donating —and highly publicizing— shipments of vaccines and other forms of pandemic relief to Honduran and Guatemalan communities.

Guatemala

The U.S. government first pledged a shipment of 500,000 vaccine doses to Guatemala on June 3, but during Kamala Harris’ trip days later, they upped the number to 1.5 million doses. For the Giammattei administration, that seems to be the high point in a beleaguered vaccination effort.

A contract gone wrong with the Russian direct investment fund (RDIF) to deliver 8 million doses of the Sputnik vaccines has caused backlash against Giammattei, with civil society groups calling for his resignation Sunday.

Last week, Guatemalan health minister Amelia Flores asked Russia to return part of the $80 million paid for vaccines because some vaccines were not delivered.

Guatemala’s anti-corruption unit within the Attorney General’s office has requested a copy of the contract purchasing the vaccines, which the health minister has declined to provide. Prosecutor Aura Marina López of the anti-corruption unit told Guatemalan newspaper Prensa Libre the office will request the contract through a judicial order if necessary.

“Right now, we depend on the vaccines that friendly countries donate,” civil society organizations said in a joint statement on July 4. “They are acting with absolute irresponsibility and negligence in managing vaccines to control Covid-19.”

#AHORA Organizaciones de la sociedad civil exigen la renuncia del presidente @DrGiammattei:

“está actuando con absoluta irresponsabilidad y negligencia en la gestión de vacunas para controlar el Covid-19”.

Vía: @noel_solis pic.twitter.com/IftJpmdInL— Emisoras Unidas (@EmisorasUnidas) July 4, 2021

Nicaragua

Nicaragua also made a big purchase of 1.9 million Sputnik V vaccines, but so far has only received 190,000, according to Nicaraguan media outlet Confidencial.

With the aim of vaccinating 70 percent of the population by the end of the year, Nicaragua began vaccinating citizens over the age of 50 last week. But Confidencial reports the country has only received 531,00 vaccines (mainly Sputnik V and Covishield) so far, enough to vaccinate just over 8 percent of a population of over 6.5 million.

Honduras

The vaccination rollout has been crawling in Honduras, with less than 60,000 Hondurans fully vaccinated as of July 3, according to government data. Another 695,000 people —amid a population of nearly 10 million— have received the first dose.

President Juan Orlando Hernández said in May that he was considering opening a China office in Honduras, which he called a “diplomatic bridge” to help the country acquire new vaccines.

The country did not receive any vaccines from the United States until late June, when a shipment of 1.5 million vaccines arrived through the COVAX program through the World Health Organization.

“We are sharing vaccines with Honduras because it’s the right thing to do from a global public health perspective, and right for our collective security and well-being in the region,” Juan González, senior director for the Western Hemisphere told Reuters.

In the Central American countries that maintain diplomatic relations with Taiwan and not China —Honduras, Guatemala, and Nicaragua— securing Chinese vaccines has posed diplomatic challenges and threatened to damage the relationship with the United States.

“China continues to increase its presence in Central America, as warnings from the United States intensify,” writes Costa Rican political scientist Constantino Urcuyo in El Faro English. “The situation in the isthmus will continue to be one of competition rather than confrontation, but the United States will also continue with its nineteenth-century Monroe Doctrine approach to the region, pushing back against extra-continental insertions into its zone of influence.”

The need to bounce back from the pandemic, and the desire to find an alternate partner to the United States, has made Beijing’s vaccine diplomacy appealing to Central American governments, writes former Costa Rican president Luis Guillermo Solís in Americas Quarterly. But the United States, Solís explains, has been more wary of China’s growing influence in the region after a wave of diplomatic shifts in 2017 and 2018, including El Salvador’s break with Taiwan.

Recently, members of Congress have been keeping an eye on vaccine donations.

“Without U.S. engagement and leadership, our competitors will continue efforts to use their less effective vaccines as leverage to coerce Latin America and Caribbean nations in support of a diplomatic agenda inimical to ours,” wrote Senators Marco Rubio (R-FL), Bob Menendez (D-NJ), and Tim Kaine (D-VA) in a letter to Biden in May.

As the United States and other wealthy countries begin to return to some semblance of pre-pandemic normalcy, cases in Central America are steadily climbing, reaching an all-time high in both Guatemala and Honduras. It remains exceedingly difficult to get an accurate accounting of cases in Nicaragua, but reports are grim.

As vaccines trickle in as gifts from countries —the United States, China, Russia— seemingly wanting to outdo each other in a game of diplomatic one-upmanship, the people of Central America continue to contract the virus, spread it, suffer, and die. The pandemic is very much not over in Central America.

Thanks for reading. If you’ve learned from our work, consider supporting independent journalism in Central America, for the price of a coffee a month, at support.elfaro.net.