Asylum-seeker from Honduras, Carla Leiva, 32, holds her five-year-old daughter Zoe as they pose for a photo at the “Casa del Migrante” shelter for migrants in El Ceibo, Guatemala, Thursday, August 12, 2021, after they were deported by air from the U.S. to Mexico, then crossed into Guatemala by land. Central American migrants were expelled by the U.S. after being denied a chance to seek asylum under a pandemic-related ban. (AP Photo/Santiago Billy)

By Karina Muñiz-Pagán

Asylum for Sale: Profit and Protest in the Migration Industry is an insightful read at a time when words like “asylum” and “refugee” appear in the mainstream news and as a tactic of disinformation to fuel political power. What are the truths that exist beyond the surface of what most hear or read about? What do refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants have to say about their own experiences?

This anthology seeks to answer such questions. The editors, Siobhán McGuirk and Adrienne Pine, have woven together a collection of personal essays, first-hand accounts, graphic design, journalism, extensive academic research and interviews to understand the mechanisms of asylum and its global profit-making structure. The authors show how predatory capitalism is fueled by the bodies and lives of people being forced to flee their homeland.

The premise of the chapters curated here shifts the lens from the dominant discussion of a state’s moral obligation with regard to asylum cases and refugees. Instead, we come to understand the capital forces that create refugees in the first place, and how the systems and institutions built to address forced migration are too often places of profit extraction.

The book’s five sections take the reader on a global journey to understand asylum. The writers discuss pathways toward asylum, the realities of travel across borders, the waiting in limbo, the profits made from detention camps, the role of NGOs, and what happens next, from survival strategies to mass deportations.

These systems of exploitation and profit are decades in the making —centuries, really, as residual colonialist structures. This will not change unless the institutions themselves change. As Marzena Zukowska notes in her essay, “The Cost of Freedom,” we must interrogate “how xenophobia, racism, anti-Black and anti-poor sentiments drive the lucrative activity of incarceration —one that at its core exploits those already living at the economic margins.” She notes that without radical social change, corporate interests will continue to find ways to monetize every aspect of the immigration process. This “will require many strategies including cutting off the monetary bloodline of the prison industrial complex and targeting institutions with links to the prison industry.” Zukowska highlights grassroots organizations like the Queer Detainee Empowerment Project whose founder, Jamila Hammami, advocates for a “reform-to-revolution” approach. Through crowdfunding to raise bonds, for example, they work as best they can to stop the immediate suffering of people who are detained, while also organizing against immigration prisons and bonds rooted in exploiting the already poor.

Resistance is found in different ways and illustrated throughout the anthology. In “The Poetics of Prison Protest,” authors Behrouz Boochani, who was incarcerated for six years in an Australian-run immigration detention center on Manus Island, and Omid Tofighian show narrative power as a form of protest. As Tofighian notes, “Behrouz used social media throughout his years imprisoned on Manus Island, live reporting events and processes that the Australian government sought to hide from view to tens of thousands of international followers.” The chapter features tweets Boochani sent at great risk to document what was happening. During his time inside, he also wrote his book No Friend but the Mountains: Writing from Manus Prison, awarded two Victorian premier’s literary awards in 2019, and now translated into numerous languages and soon to be made into a film. In Boochani’s acceptance speech, given via WhatsApp while still imprisoned, he said, “after years of struggling against the system that has completely ignored our individual identities. … This proves words still have the power to challenge inhumane systems and structures. … I believe that literature has the potential to make change and challenge structures of power. Literature has the power to give us freedom.”

Resisting, exposing, and creating another way forward is how we can transform our society and dismantle these violent profit-making systems, as Seth M. Holmes notes in the foreword. Holmes reminds us that we all exist in some relation to the asylum industry, and must consider our complicity and ways in which we can join in solidarity with people seeking refuge.

The book is a must-read for anyone who cares about human rights, migration, and is interested in how to resist the global profit-making industry of asylum and find another way for all to be truly free.

***

Here is an excerpt from the book “Asylum for Sale: Profit and Protest in the Migration Industry”:

Beds, Masks, and Prayers: Mexican Migrants, the Immigration Regime, and Investments in Social Exclusion in Canada

By Paloma E. Villegas

Discussions about Mexicans’ migration routes do not regularly conjure Canada. However, the number of Mexican migrants (with varying immigration statuses) to Canada has increased since the mid-1990s. There are several reasons for this. First, growing insecuritization in Mexico, stemming from actions related to organized crime and the “War on Drugs,” as well as government policies to keep working-class Mexicans in precarious livelihoods, has led Mexicans to seek security abroad. Second, migration to the United States, the primary destination for Mexicans, has become more difficult. Security measures at points of entry, as well as within US borders, have intensified in the last few decades, with particularly punitive rhetoric and actions after the 2016 presidential election. Third, until 2009 (and once again after December 2016), Mexicans did not need a visa to enter Canada.

While the Canadian immigration system is often depicted as more accessible than that of the United States, Mexicans in Canada face significant difficulties accessing permanent residence unless they fit into skilled worker immigration streams or are eligible for a narrow conception of family reunification. Those excluded from such applications fall into what Goldring, Berinstein, and Bernhard term precarious immigration status, an umbrella category that includes temporary foreign workers, international students, spouses undergoing the sponsorship process, undocumented migrants, and refugee/asylum claimants.

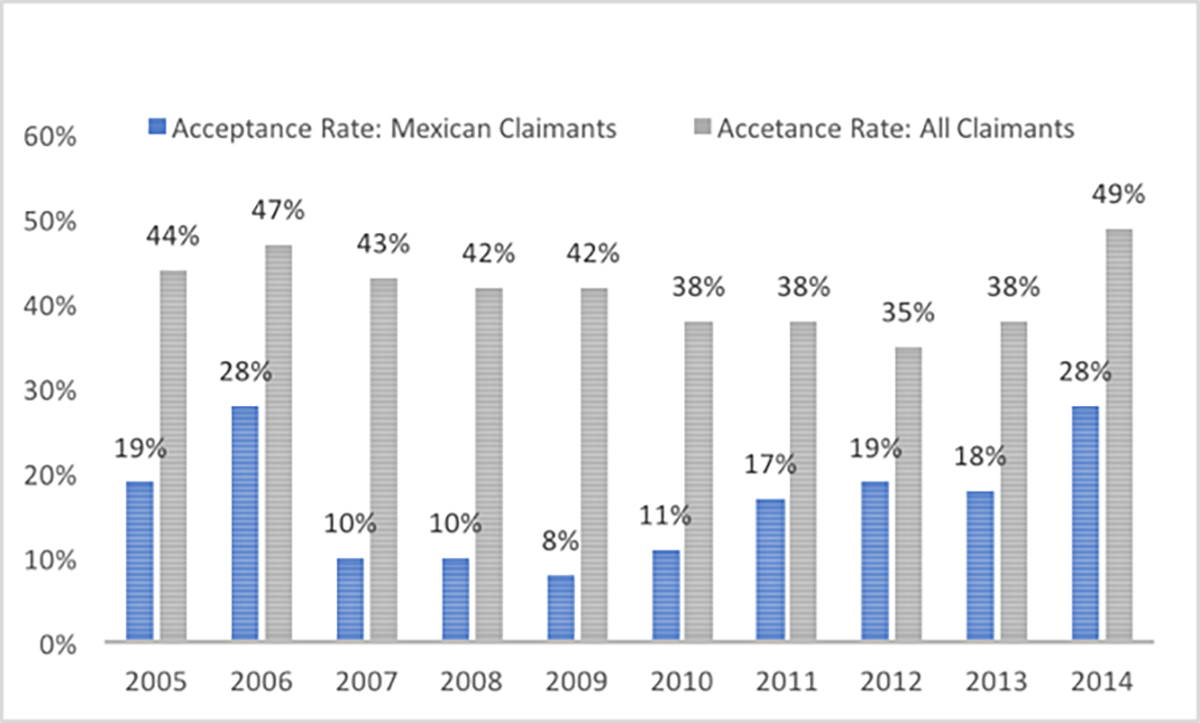

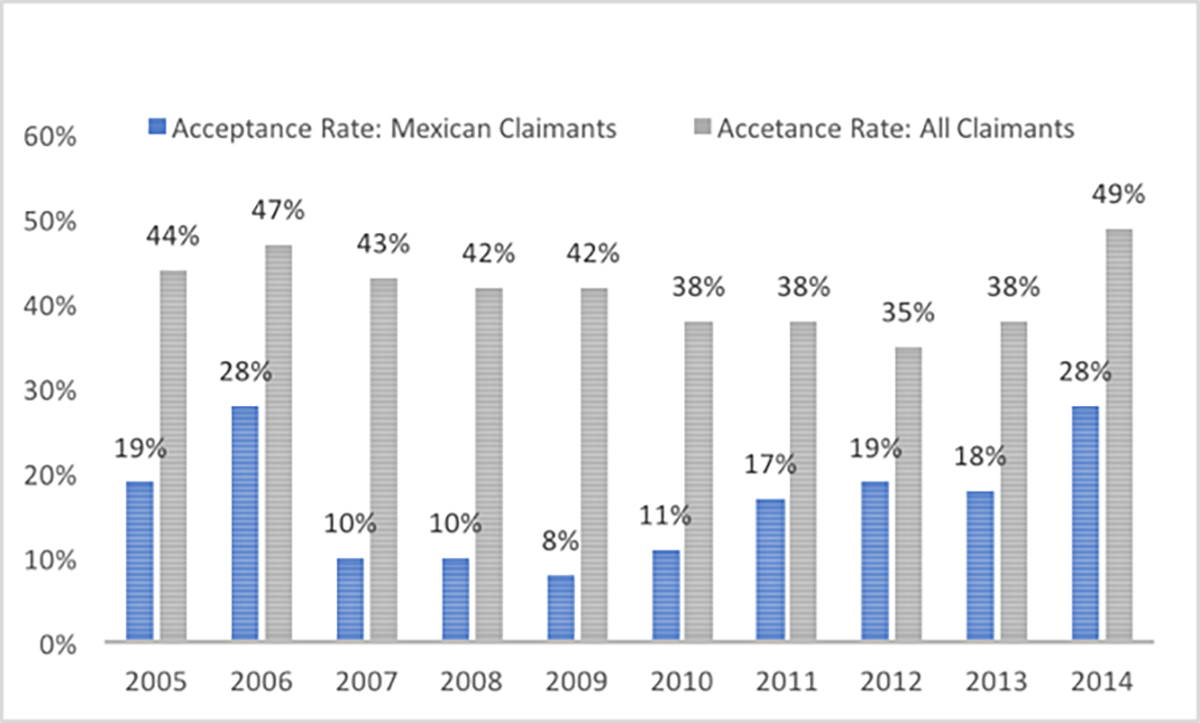

The process of applying for refugee/asylum status in Canada is difficult to navigate. There are two avenues to apply for refugee protection in Canada. The first involves an application for resettlement from abroad (often from refugee camps) alongside a referral from an organization like the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). The second, for which Mexicans are eligible, can only occur inside Canada. Applicants apply at the border or at an immigration office, are evaluated in terms of eligibility to apply, and then must provide specific evidence to prove that their need for protection aligns with the criteria outlined in the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA). Applicants must outline their case and provide evidence in support of it. This process involves investment of time, energy, and money (lawyers, translation fees, and shipping costs for documents), as well as the emotional labor needed to relive trauma and to perform it in a way that is palatable and legible to immigration authorities. Sometimes those investments are not enough. Approval rates for Mexican refugee/asylum claimants have ranged between 8 and 28 percent in recent years (see figure 22.1).

Figure 22.1: Refugee approval rates: Mexican claimants compared to all claimants (Data source: Citizenship and Immigration Canada)

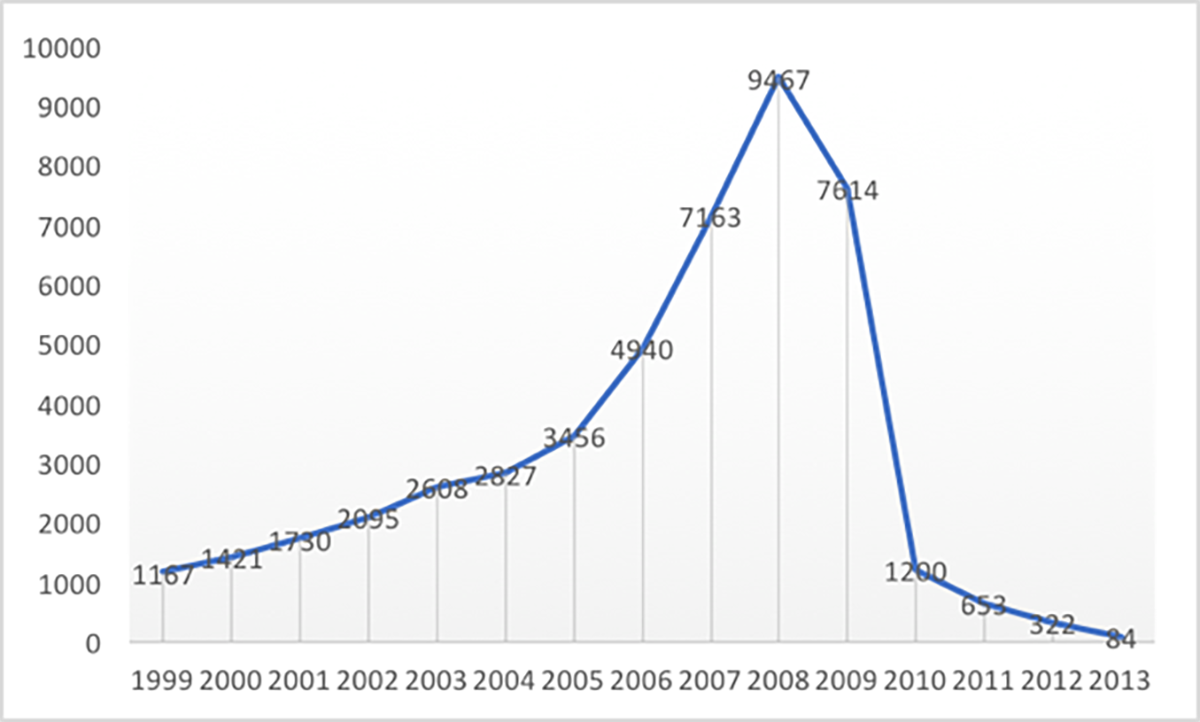

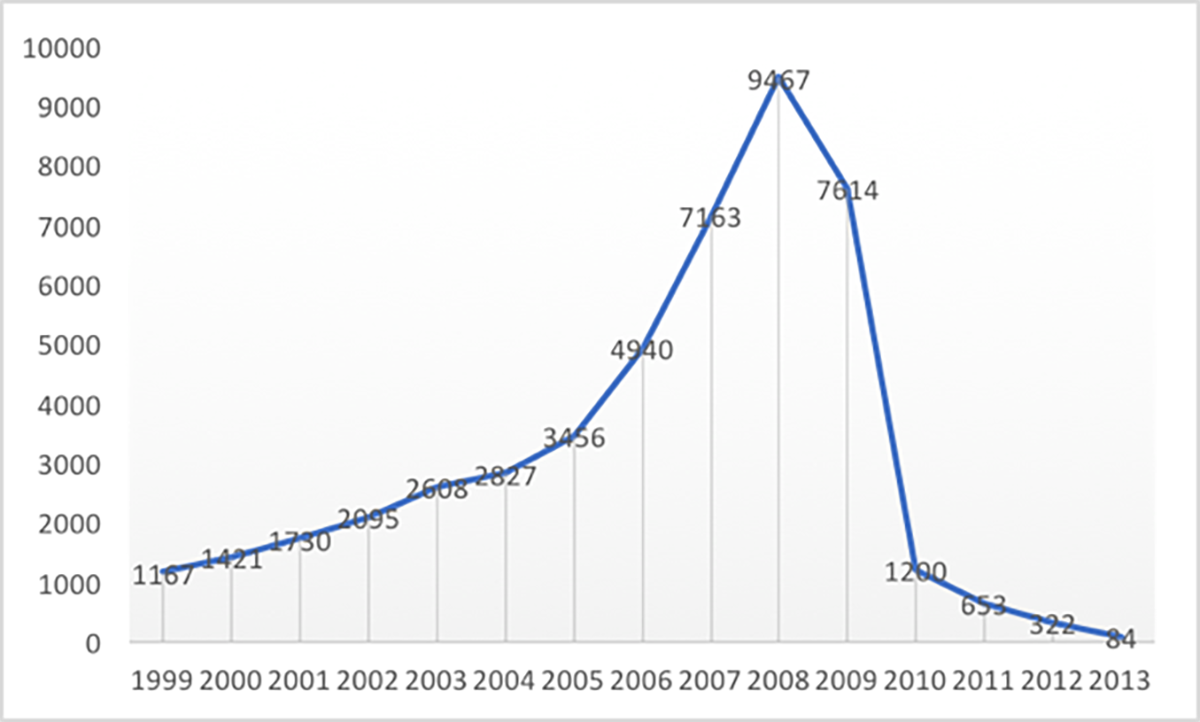

To contextualize this shift, refugee/asylum applications from Mexican nationals prior to 2009 made it a top source country (see figure 22.2). The Canadian government’s response to the high number of applications was to identify Mexican claimants as “bogus”—using the low acceptance rate as evidence to support their rhetoric. As I write in Ethnic and Racial Studies, this maneuver positioned Mexican claimants as undeserving of protection and legitimized a 2009 policy that required Mexican nationals traveling to Canada to have an entry visa. Additionally, in 2013, the Canadian government identified Mexico as a “safe country” for the purposes of refugee determination, making it more difficult for Mexicans to successfully apply for protection.

Number of claims by Mexican nationals (Data source: Citizenship and Immigration Canada)

As a Mexican migrant in Canada, an immigration scholar, and an artist, I analyze the case of Mexican precarious-status migrants in Canada using three art pieces.8 Each piece draws from my research findings and personal experience. I arrived in Canada in 2006, after having lived in the US undocumented for almost fifteen years. In 2009 and 2010 and again in 2014 and 2015, I conducted research with Mexican precarious-status migrants in Toronto, interviewing a total of twenty-one participants.

I propose that Mexican precarious-status migrants in Canada, particularly refugee/asylum claimants and undocumented persons, experience what Menjívar and Abrego term “legal violence”: explicit and implicit violence enacted by the government and its legal systems on non-citizens. In this case, the barriers produced by the immigration system through limited access to refugee protection and permanent residence lead to violent encounters in terms of employment, access to social services, and the navigation of everyday life. For Mexican refugee/asylum claimants, one way legal violence operates is through low acceptance rates and the reasons provided for those decisions: Mexico is “safe,” and Mexicans can relocate to internal flight alternatives (IFAs)—urban areas or far-off sites within the country—if they feel unsafe in a particular region. Low acceptance rates send a message to potential applicants that they should not apply for protection, because the likelihood of approval will be low. This violence renders refugee/asylum seekers vulnerable to detention and deportation, the day-to-day operations of which are often outsourced by the state to private companies. Their vulnerability in turn creates profit-able opportunities (linked to further violence) for individuals and companies offering informal employment and services outside the public sector, as well as entities profiting from the immigration industrial complex.

In this context, legal violence involves at least three types of investments. First is an ideological investment in a Canadian national narrative that depicts its systems as fair and generous, ignoring the outcomes of its immigration policy. Second is an investment in fiscal responsibility and austerity that portrays Mexican refugee/asylum claimants as “abusing” the system by applying for protection and accessing social goods during that process. During the application process, claimants have access to ESL courses, health care services, social assistance, including some legal aid, and can apply for a work permit. Given the high rate of unsuccessful refugee/asylum claims, the third investment involves maintaining precarious-status migrants in an exploitable existence by refusing to recognize migrants’ claims or by preventing migrants from making claims. This process, as noted above, allows the Canadian nation-state and economy to profit from the labor of precarious-status migrants, who have difficulty exerting their rights, given the possibility of being deported. This is particularly salient when considering the unsafe working conditions inherent in the jobs available for such migrants. They often experience an interlocking of difficult physical work conditions and psychological abuse, with women migrants also facing the possibility of sexual violence.

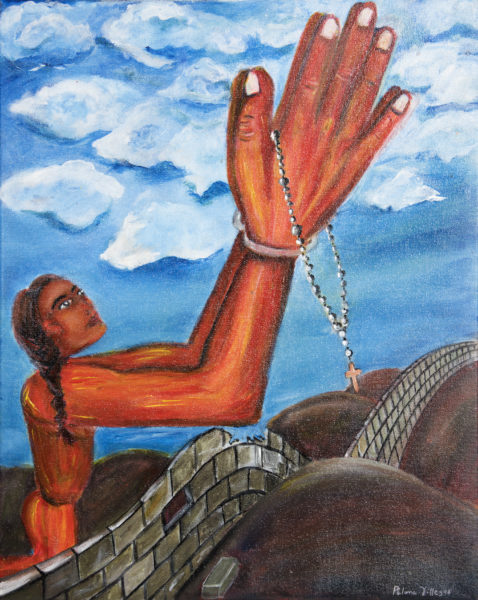

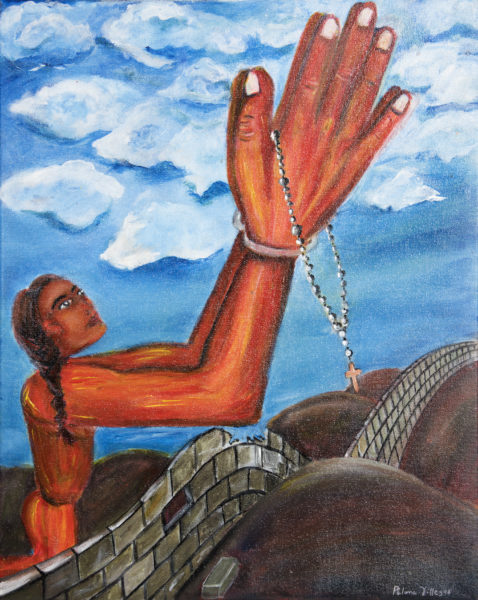

Pleading at the Border depicts the relationship that refugee claimants are often assumed to have with the nation-states they apply to for protection: seeking sanctuary from a benevolent entity. The border in the painting can be imagined in two ways: a port of entry and an internal border. At the port of entry, migrants are asked about their intent to stay in Canada, often in a humiliating manner. Sometimes those who apply for protection are held in detention centers, marked as “flight risks.” The painting illustrates the yearning for security that many migrants experience and the violence and investments (in terms of immensely expensive walls, fences, and technologies of interdiction and detention) that nation-states enact to manage migration. Once migrants enter a nation-state, they face internal borders that create wealth for others while inhibiting their chances for survival—barriers that curtail their ability to access social services and work and limit their freedom to move around the city, particularly if their refugee/asylum claim is refused. Yet migrants engage in resistance to the xenophobic capitalist state. This is illustrated through the brick that has been dislodged from the border onto the floor.

“Pleading at the Border” by Paloma E. Villegas

Borders also have a temporal aspect. For those able to apply for protection, awaiting the resolution of their case can be stressful. I Can’t Even Buy a Bed Because I Don’t Know if I’ll be Able to Stay references Berenice (pseudonym), a Mexican woman I interviewed in 2009, who explained her inability to purchase material goods, because her refugee claim might be refused. Berenice’s account demonstrates the temporal, spatial, and economic limbo that refugee/asylum claimants are placed in as they await the resolution of their applications or the opportunity to apply under a new application. This process can often take years and greatly exacerbate the financial insecurity migrants experience as a result of their liminal status. While it does not prevent the possibility of making plans for the future, it can greatly curtail them as a result of multiple insecurities. The bed, while representing an everyday household item, also signals a location of rest, something that is hard to come by with the continued threat of detention and deportation. The painting facilitates a discussion about the types of investments governments make to exclude precarious-status migrants from Canada’s territory and institutions. For Mexican refugee/asylum claimants, one way this legal violence operates is the establishment of a low acceptance rate (explained above), which can increase migrants’ experiences of a legal limbo.

“I Can’t Even Buy a Bed Because I Don’t Know if I’ll be Able to Stay” by Paloma E. Villegas

Finally, borders are also racialized, another aspect of legal violence. Gringo Mask references Teresa, whom I interviewed in 2010, and who pro- posed wearing a mask to look like a gringo (a white North American) to pass as having secure immigration status. However, as the painting demonstrates, because of a person’s features, skin color, and accent, as well as lack of documentation, wearing a mask is futile. That is, the different markings of the body can betray the mask shown to the world. The mask also signals the way Canada operates according to an ongoing white settler identity, while at the same time marketing itself as multicultural and inclusionary. Henry and Tator define this type of democratic racism as:

an ideology that permits and justifies the maintenance of two apparently conflicting sets of values. One set consists of a commitment to a democratic society motivated by egalitarian values of fairness, justice and equality. In conflict with these liberal values, a second set of attitudes and behaviors includes negative feelings about people of color that carry the potential for differential treatment or discrimination.

“Gringo Mask” by Paloma E. Villegas

Democratic racism produces the mirage of a “color-blind” society and ignores the ways immigration status and racialization intersect to identify migrants of color as detainable and deportable. It also demonstrates the investment in identifying Mexicans as “bogus” to facilitate the rejection of their refugee/asylum claims and uphold the idea that the Canadian refugee determination system is fair.

Ideological and economic investments influence the violence migrants experience when they have a precarious immigration status. While Canada’s system of immigrant detention is not officially a for-profit enterprise, there are numerous sites of profit-making that depend on the existence and vulnerability of precarious-status migrants. Ideologically, Canada’s reputation profits from a global identification as an immigrant-friendly country, a process that makes invisible the racism and xenophobia that exists in its immigration policy and promotes an ever-ready reserve army of precarious labor.

While Canada’s migration system for “skilled” workers touts itself as “color-blind,” focusing instead on human capital—education, work experience, and the “soft” skills required to navigate working at Canadian firms (what is often referred to as “Canadian experience”)—this class-based system obscures racist forms of exclusion involved in evaluating the “quality” of applicants’ skills. Furthermore, wealthy applicants (in need of protection or not) can bypass many application requirements if they invest a certain amount of money in Canada. A second profit-making process occurs through labor exploitation, particularly because precarious-status migrants receive minimal protections. This makes them vulnerable to violence at the hands of state officials, employers who engage in wage theft and other violations, and health care providers whose fees for uninsured patients are unregulated. Third, profit-making occurs through application and other fees. For instance, approved refugees (those whose refugee/asylum claims were deemed “legitimate”) have to pay processing fees to apply for permanent residence, which provides them with a more secure immigration status. Claimants might also be asked to pay legal, translation, and other fees if they are deemed ineligible for legal assistance. These investments intersect to uphold a legal violence that denies precarious-status migrants security by maintaining insecure living conditions and the threat of deportation—in turn creating profit opportunities for others.

***

Karina Muñiz-Pagán is a queer Xicana prose writer of mixed-heritage with roots in San Francisco and the El Paso/Juarez border. She has an MFA in Prose from Mills College where she was the Community Engagement Fellow and taught creative writing to members of Mujeres Unidas y Activas, a Latina immigrant rights organization where she also served as Political Director. As a result of the generative workshops, Karina co-founded the writers’ group, Las Malcriadas, and edited and translated the bilingual anthology Mujeres Mágicas: Domestic Workers Right to Write, published in 2019 by Freedom Voices Press. Karina is currently working on a memoir called Flygirl about her search for home as a queer Xicana, community organizer raised on Hip Hop, and her political education journeys throughout the US, México, South America, Asia and Europe. Twitter: @KarinaM_P

Paloma E. Villegas is an interdisciplinary artist and assistant professor of sociology at California State University San Bernardino. Her research examines the production of migrant illegalization and its intersections with race, gender, and class. She is the author of North of El Norte: Illegalized Mexican Migrants in Canada (UBC Press, 2020). Twitter: @Nopaldove

why should a person entering a country illegally be allowed to access social services?

[…] Karina Muñiz-Pagán Latino Rebels October 14th, […]

[…] Karina Muñiz-PagánLatino RebelsOctober 14th, […]