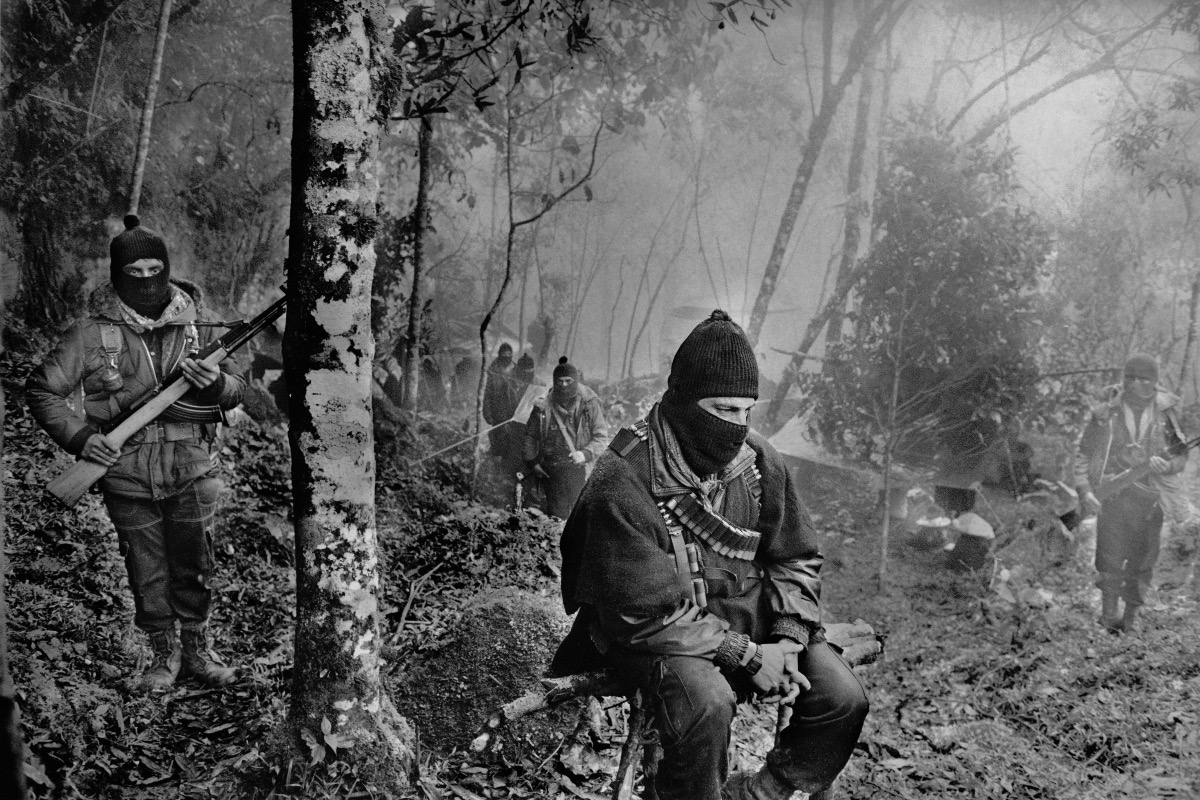

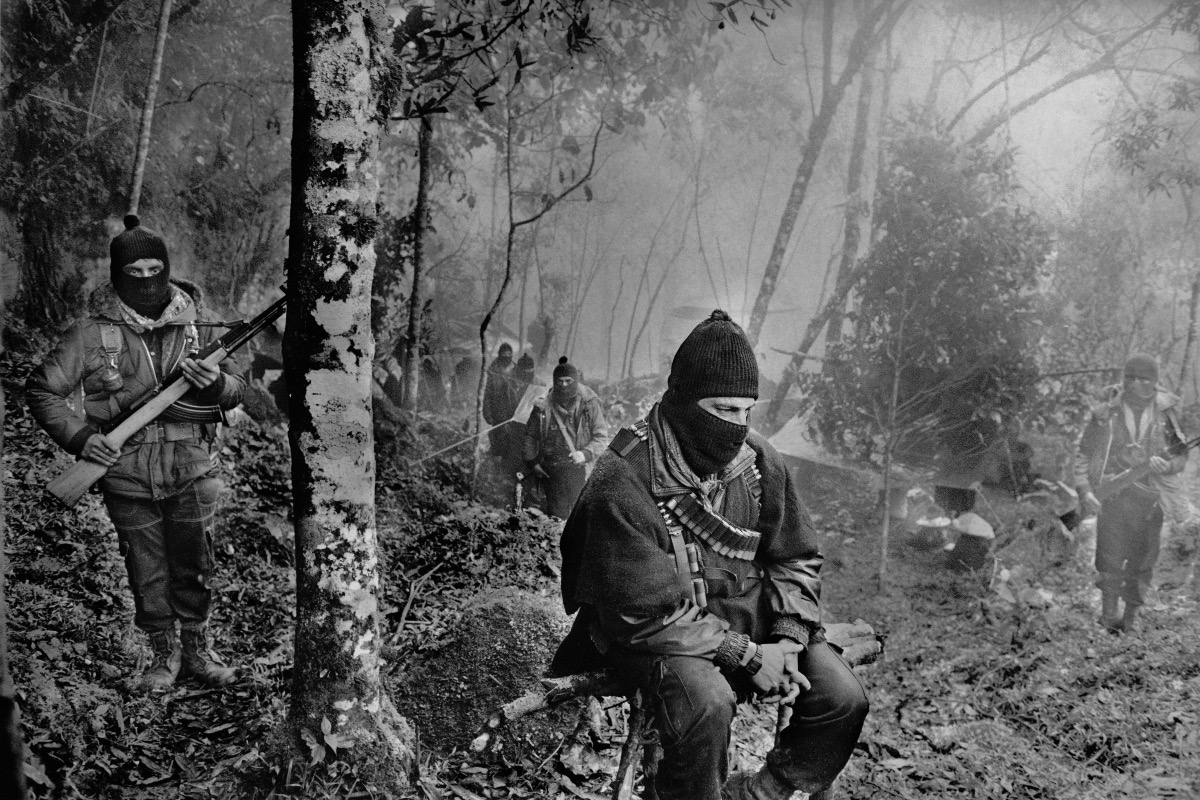

‘Subcomandante Marcos, montañas del surest’ by Antonio Turok, 1994

Eastern Projects Gallery recently brought renowned documentary photographer Antonio Turok to Los Angeles for a solo show. The series of photographs in “The End of Silence,” which ran from October 9 to November 27, documents a 40-year span that mirrors Latin American and Indigenous cultures whose fundamental core of existence is communal. Graphic images of death and life are wrapped around war, the struggle for self-determination, rebellion, revolution, suffrage, loss, and hope. Turok’s exhibition carries the turbulent history of Indigenous and mestizo communities. Despite attempts by modern states to eradicate millennial Indigenous epistemologies and cosmovisions, they continue to survive and thrive under extreme institutional and state-sponsored violence 40 solar years later.

For Eastern Projects’ Chicano owner and director, Rigo Jimenez, this exhibition is “very iconic and truthful to Mexico and Latin American realities.” He adds: “People need to see why people were leaving. Forty years later people continue the exodus!”

By the 1970s and 1980s, revolution and social crises in Central America forced many to migrate to the U.S. Several of these countries were governed by conservative right-wing governments, military juntas, and oligarchies with the full support of the U.S government.

By the early nineties, neoliberal economic policies in Mexico and Latin America would generate another wave of migration to the U.S. Asymmetrical trade deals like North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, which benefited the U.S and Canada more so than Mexico, contributed to the further impoverishment of peasants, workers, and families. Neoliberal policies brought the deterioration of state social services and workers’ rights all across the continent. Land grabs by the bourgeoisie along with the shift from traditional agriculture to transnational agribusiness increased internal tensions across Latin America.

In a 2017 interview, Turok poses a question: “Have we really learned anything from history?” Perhaps the answer is yes, with the exception that there are many actors in charge of dismembering truth. Clearing out truth from lies is what makes Turok’s work a valuable experience for all generations and people from all walks of life. It is a daring act to come face to face with an unknown reality especially when it questions our perception and our indoctrinating beliefs.

His medium of choice of black-and-white photography eliminates the distraction that comes with color photography, allowing Turok to remove the blinders to the rawness of the present world order. In the most restrictive moment of photographing under fire, Turok’s composition seems to come second to the visual narrative drama captured in his work.

What stands out in “The End of Silence” is the will of life as an act to no longer live in silence. Turok spaces in images of memory as stored energy. To recollect experiences in film emulsion all too ready to engage in conversation with the present is crucial for Turok.

And for a place like Los Angeles, this exhibition is very relevant. The city holds one of the largest diasporas of refugees, immigrants, and second-generation Americans from Central America dating back to the eighties and nineties. It is a relived memory brought by a Mexican photographer to the doorsteps of L.A.

‘Widows of Guatemala’ by Antonio Turok, 1989

In Widows of Guatemala, taken in 1989, every square inch of the image is occupied with the presence of Mayan Guatemalan widows who endured violence, rape, and the loss of loved ones during the civil war. Despite its beauty, it is a chilling photograph. The civil war in Guatemala between the military dictatorship and peasants, children, workers, elders, students and indigenous communities is one of the bloodiest in Latin American history. For scholar Susanne Jonas in The Battle for Guatemala: Rebels, Death Squads and U.S. Power, the displacement of peasants (Ladinos and Indigenous) and land appropriation of communal lands by the elite with the aid of the U.S. was the direct cause of Guatemala’s civil conflict. Over 440 villages were entirely destroyed. Jonas describes the scorched-earth polices as genocide and a covered-up holocaust.

The title of this image hints at the tragedy of war in particular for women and especially if they’re Indigenous. If interpreted as past tense, we lose the significance of Widows of Guatemala, hence acknowledging the suspended closure and mourning which continue to this day. Despite moving along with life, the hurt and trauma is a new tenant in the heart and mind of many in Widows of Guatemala. It is a silent hurt, an invisible scar.

Regarding the dismembering colonial practices towards non-Western cultures in Something Torn and New: An African Renaissance, writer and scholar Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o poses the following questions: “What are the consequences of lack of mourning?” And “how does it impact or disrupts the collective experience or those involved?” These are fitting questions to be examined by all of us.

Turok’s work is a visual interpretation of Eduardo Galeano’s book, Open Veins of Latin America. Hence, the presentation of this series is a “construct of memory built to … ‘bring into appearance‘ a community historically neglected, un-acknowledged and discriminated against.”

What can we extract from Turok’s exhibition other than the drama in this body of work? Besides an aesthetic consideration, this selection of photographs consists of accumulative historical moments that circumvent between the past and an unknown future. What arises is a dialogue between two thinkers, W. E. B. Du Bois —“the problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line,” or racism— and Jose Carlos Mariategui’s argument of the Indian problem as “the land problem.” Both of their arguments can be traced to the early years of the colonization of Abya Yala (Latin America).

Following the signing of NAFTA in 1993, the Zapatista rose up in Chiapas, Mexico, drawing the world’s attention to the perverse logic of domination by a modern colonial world system against people in the Global South. Images of anti-imperial and anti-capitalist guerrillas circled the planet. In other words, they were and continue to be the first responders “denunciating the New World Order from that order’s victims.”

“Who were these masked and multicolored Indians with makeshift weapons?” the late Tom Hayden asks in his introduction to The Zapatista Reader. The Zapatistas’ proyecto de vida (project of life) against los malos gobiernos is contained within many of Turok’s images. He captures the solidarity muscle behind the rebel group. Turok decompresses the lived experiences from the confinements of a time capsule that would otherwise be lost in space. His gentle click on the camera forwards, “from a real body which was there, proceeds radiation which ultimately touches me who am here,” as Roland Barthes writes in Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography—hence, Turok’s direct presence as a witness to the many struggles. The spirit in several of the images is one that cannot be at rest; it interrogates us in the present. Turok’s photo documentation consists of “thinking images“ charged with feelings and emotions.

In Subcomandante Marcos, montañas del sureste (featured image), taken in 1994, the Zapatista mestizo poet leader is pictured sitting on a log in deep thought, his fingers intertwined, accompanied by guerrillas. The background is a dense jungle veiled in clouds. El Sub is etched with the transmission of light in the same likeness as Auguste Rodin’s bronze sculpture, The Thinker—except Subcomandante Marcos is not alone nor is he nude, but in the company of a bandoleer across his chest, full of rounds, in a jungle that breathes him and the rebels support and love while a mist descends from the heavens to blanket them all with protection.

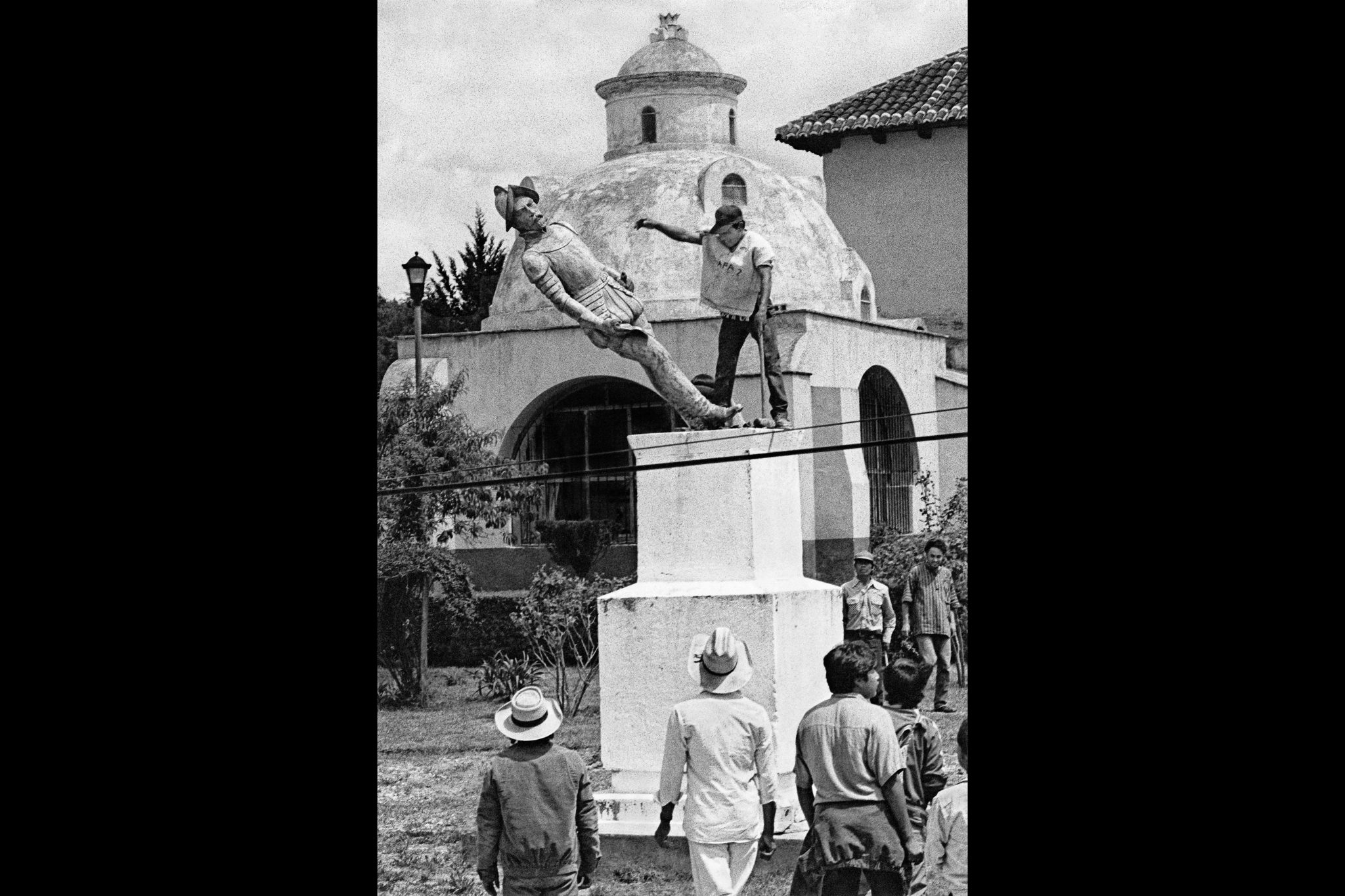

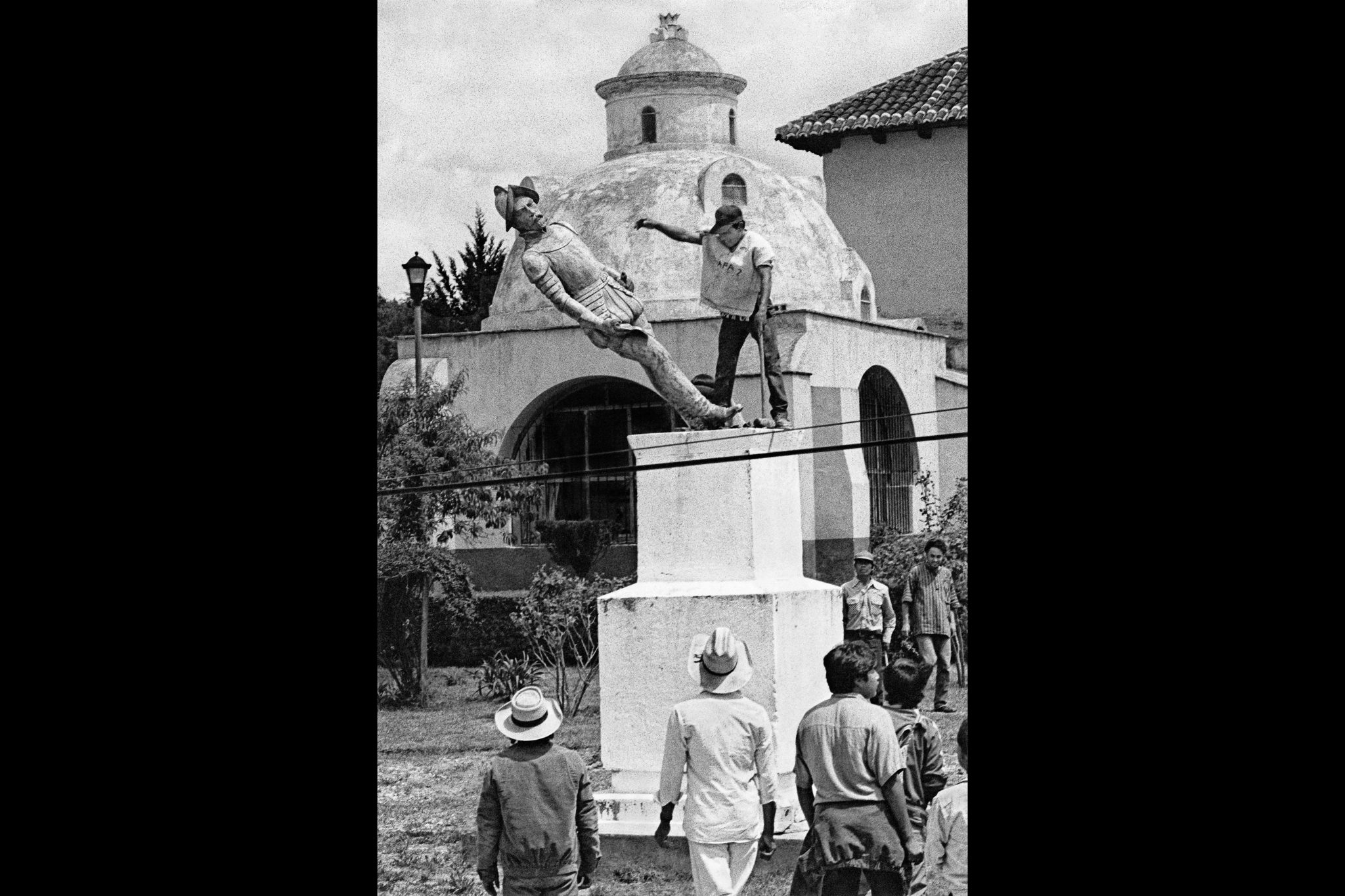

‘The Collapse of Don Diego Mazariegos’ by Antonio Turok, 1994

In 1992, while some celebrated the 500th year since the discovery of Las Americas, thousands across the continent protested and celebrated 500 years of resistance to Western colonization. That same year, Turok would capture with a click “The Collapse of Don Diego Mazariegos,” in which a bronze monument of the conquistador and invader of Chiapas is toppled in a village square. Like those of other conquistadors, the colonial monument to Don Diego Mazariegos represented “a conversation of we don’t belong together.” Upon impact with the ground, the bronze sculpture’s head would come off and be carried through the town by locals as the unmasking of silence.

The most subtle image in the exhibition is also one of the most striking. The scene in Church of San Andres, Sakamch’en de los pobres, taken in Chiapas in 1994. A silver gelatin print smokes the dramatic sunlight rays with incense, the sunlight drawing directly upon the body of the poor families kneeling in prayer. They worship perhaps with the same humble devotion and veneration as did many of their past ancestors prior to colonization. Cempazuchitl (Mexican marigold), candles, saints and bows adorn the inside of the church with a dynamic aura of quietness. The image, to borrow from Susan Sontag, strikes your skin like a delayed ray of a star.

“Church of San Andres, Sakamch’en de los pobres’ by Antonio Turok, 1992

The consistency in Turok’s photography brings to mind scholar Hugo Zemelman. Zemelman discussed the need to first acknowledge what determines and does not determine our circumstances. Second, whatever does not determine us is what allows us the space to understand “El Hombre” as a creator or a constructor of the new. In other words, Turok’s images challenge modernity’s deterministic attitude towards the poor, people of color, and the Global South.

The silver emulsion in Turok’s black-and-white photography, unlike digital, carries the mystic silver rays of Tonantzin, the Great Mother goddess of Mesoamerica. It is what allows his work to glow out of darkness.

Turok can best be described as a brujo (wizard) who traps the lives and souls of many with his camera. He descends with his black camera into Mictlan, his dark room, to bring back to life testimonies that would otherwise go untold. In this journey, Turok carries with him the spilled blood and the dust of hope. Every so often he releases the energy of these photographs in spaces known as galleries and museums as a soul-cleansing ritual for all to engage in. The energy as resurrection then walks amongst the living, whispering their unknown stories and testimonies of cruelty and challenges.

Like Juan Rulfo’s novel, Pedro Páramo, it is the lifelike aura of the dead as storytellers in much of Turok’s work that haunts the present. In the first sentences of Pedro Páramo, the dying mother pleads with her son to not ask his estranged father for anything: “Just ask for what he owes us.”

The silent co-authors of “The End of Silence” do not ask for anything. They fight for what is owed to them—dignity, justice, and peace. They fight against the very same system and people who have deemed them backward and useless for modernity.

—

Note: To schedule Antonio Turok for a lecture (Zoom or in-person) on his brilliant black-and-white photography, email Dr. Álvaro Huerta.

***

Jimmy Centeno holds an associate’s degree in liberal arts from East L.A. Community College, a bachelor’s degree in Latin American studies from Cal State Los Angeles and is concluding a second master’s in art history.