Evelyn, a Salvadoran immigrant on Temporary Protected Status (TPS)x, and her husband, who is also Salvadoran but is not on TPS, at the “Day Without Immigrants” rally in Washington, D.C., on February 14, 2022. (Ali Bianco/Latino Rebels)

ARIZONA BORDER, June 1999 — It has been two days and two nights of trudging through the Arizona desert. Faustino’s left leg is lifeless. As his feet drag through the sand, he recalls his previous endeavors at this same malicious journey.

The first four attempts remain largely a blur of dust, heat, and severe dehydration. The fifth he spent taking care of a six-year-old boy crossing with no guardian. After the sixth, he was exhausted. It had been two months of trying.

He pushes forward this seventh time until he finds a car to take him to Los Angeles.

He doesn’t realize he’s six months too late.

SANTA ANA, El Salvador, 18 Months Later — With earthquakes come destruction, and crime quickly follows. Landlords extort Evelyn’s family business by raising rent prices. The streets of Santa Ana grow less safe by the day, but they are also the same streets where she’s taken her first steps. This is the same land her father has fought for 17 years to protect as a member of the Salvadoran military. Now, her family is preparing to leave.

Evelyn’s mother has received a two-month tourist visa to the United States—a longer than average vacation, but still temporary. Not long after Evelyn, her parents, and younger sister arrive in Aspen Hill, Maryland, a 7.6 magnitude earthquake wrecks El Salvador. Two months later, Evelyn’s family has to face their new reality—they are not returning home.

From 1999 to 2001, Honduras, Nicaragua and El Salvador were designated for Temporary Protected Status (TPS), an executive federal protection for immigrants from countries suffering natural disasters, instability, and armed conflict. Still, TPS is not automatically granted but must be applied for by eligible individuals. Of the 400,000 immigrants currently on TPS, over 300,000 of them are from Central America.

Evelyn’s family came as the TPS designation was announced. With the possibility of their eligibility, they weighed their options, but Evelyn knew it wasn’t much of a choice—they would be at risk if they returned.

“My mother told me, ‘What do we do?’ The earthquake made everything worse in El Salvador,’ says Evelyn. “It’s traumatizing.”

Central American migrants discuss their journey using a map posted inside the sports complex where thousands of migrants have been camped out for several days in Mexico City. (AP Photo/Rebecca Blackwell, File)

Evelyn, her little sister, and their parents settled in Maryland. She celebrated her 16th birthday a few months after arriving, welcoming a new chapter of her life but mourning the loss of her childhood in Santa Ana. She started going to English classes with her younger sister as her family waited to be approved for TPS.

“In El Salvador they teach you in schools, but it’s different from here,” says Evelyn. “I was trying to learn in this little school where you paid for classes, and all of us were Latinos there. But it wasn’t the same as a high school where you have to speak English. It was hard at first, at least for me.”

Towards the end of 2001, their application had been accepted, and she was able to enroll in public school. “You felt a bit freer to do things,” Evelyn recalls. “Because when you don’t have a status, it’s scary.”

This is a fear that Faustino has lived with since he arrived in Arizona. The announcement of amnesty for Hondurans suffering from political instability and the devastation of Hurricane Mitch occurred before he found a ride to Los Angeles. Any Hondurans in the country as of January 5 were eligible. He arrived six months later.

But like Evelyn, Faustino didn’t have the option to return to his home country.

“There were friends of mine that were killed to be stolen from, to take their money,” Faustino says. “They killed a friend of ours. Our lives were in danger, so my dad decided that I should find a different future.”

To get to the U.S., he went through El Salvador, then Guatemala, paying his way through until he got to Mexico. There he was shoved into the bottom part of a truck under a stack of bananas with 50 other people, praying they would get past the security checkpoints.

Once he got to Arizona, his mission was to meet up with his family in New York. Eventually, he moved to Virginia and started a life there, without papers. Evelyn stayed in Maryland. She was constantly renewing her TPS.

MARYLAND, 18 Years Later — Jesly watched her mom watching TV TV, confused as to why she looks so distressed. A reporter was talking about the Trump administration’s attempt to shut down the TPS designation for many Central Americans who have been in the country for almost 20 years.

Jesly’s father had been deported in 2010 to Guatemala. It was not something she had ever hoped to relive.

“Mami, you can’t go back to that country,” Jesly told her.

Evelyn had left El Salvador so young. She had no idea what they would do, where she would work, if she was sent back.

In 2018, the Trump administration attempted to end TPS for El Salvador, Nicaragua and several other countries. A district court blocked the order, but an appeals court reversed the decision.

Photo via the National TPS Alliance

“(Jesly) started to understand that the risk that I could be deported is there,” says Evelyn. “She didn’t know that because (my children) were born here, they have all of these rights. Because we are immigrants we don’t have that, we don’t have the privileges to travel or have what they have.”

Evelyn’s husband, Jesly’s stepfather, is also Salvadoran. But he is not on TPS. When the potential of deportation started to grow in 2018, they discussed what would happen in the worst-case scenario.

She knew she couldn’t hide from Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). Every 18 months, she gave them all her information, her address, her job title, even her fingerprints. They knew where she would be if they took her TPS away.

After the legal and political complications that came with trying to end the TPS program, status holders have their TPS extended yearly. But Evelyn’s TPS card is technically expired, with the date on it ending in 2019. Since then, immigrants on TPS have had to wonder if their expired cards might cause problems for them.

“The first time it worried me because when they didn’t let us reapply, my work told me to bring a physical card, which I told them I don’t have. I called immigration and they told me that this pop up on their page was the only thing to show,” Evelyn remembers. “Thankfully, my work accepted that announcement but if they hadn’t, then I couldn’t work.”

A new TPS designation for El Salvador would include Evelyn and her husband. She explained it would give her a new card and provide security to her and her family.

But for now, she says she is hanging by a thread.

“It was terrifying, and still is,” says Evelyn. “Because it’s still just an extension. It’s scary because I have my job, I work for the government and I have my kids under my insurance, using my benefits. And that’s when the fear sets in. What if I lose my job? We bought a house in 2017 with my husband, and you wonder if you don’t have this status then maybe you’ll lose your house. And finally, what about my kids? It’s a fear of not knowing what will happen in the future. It’s uncertain.”

VIRGINIA, 2018 — Joseph’s mother and father knew he was a rising star. An honor roll student and lover of sports and mathematics, he was gearing up to apply to college. He turned 18 soon, and would have opportunities his father never did. The one thing holding him back wasis fear.

As night arrived, Joseph flipped through his calculus book mindlessly. From the kitchen table, he tapped his foot, turning toward the door. More time passed with no homework done.

Finally, his father walked through the door. Joseph let out a sigh of relief.

To Joseph, Faustino is as worthy as any American citizen. His father makes excellent food, works as a chef and has always provided for their family. But living with undocumented parents became more concerning as ICE raids and deportation rates grew.

“If I put myself in his shoes, I see how early he wakes up to go to work and keep a roof over our heads, so that we have water and food,” Joseph says. “Without him, nothing would be possible. Because of him, I’m fighting for Hondurans to have TPS and live their lives.”

A boy covered in a Honduran flag joins a march against the administration of President Jaun Orlando Hernandez and the recent decision by the U.S. government to end temporary protected status, or TPS, for tens of thousands of Hondurans who have resided in the United States for nearly two decades, on the streets of Tegucigalpa, Honduras, Friday, May 4, 2018.(AP Photo/Fernando Antonio)

If a new TPS designation were assigned for Honduras today, Faustino and his wife would be eligible for work authorizations and legal status. For their family, there is no alternative. Honduras remains unstable. The country is still recovering from Hurricane Mitch, and in 2020, it was hit by not one but two hurricanes.

“Apart from the natural disasters, during the pandemic there just weren’t any hospitals,” Faustino recalls. “They robbed the money from the hospitals. There were no vaccines until other countries donated vaccines, including El Salvador which is a smaller country. In the hospitals there was nothing.”

It is because of the ongoing conditions in Honduras that Faustino believes a new TPS designation is not only justified but overdue. Natural disasters, political instability and ongoing armed conflict—Honduras qualifies with all of these conditions, says Faustino.

“It would be a catastrophe to return Hondurans to that country. We are totaling almost two million in the U.S. If we went back to Honduras, the crime rate would rise. So would poverty. There’s no schools; they don’t even have chairs for all the kids; the teachers are underpaid. Honduras isn’t ready,” he says.

Joseph has an older sister who is applying to college now. His younger brother is five. Should his parents be deported, he fears what would happen to his siblings.

Faustino explained he could not leave his children behind. Even worse, he said being American citizens in Honduras would put a target on their back.

Faustino was Joseph’s age when he left his family behind and came north, crossing the border on foot. Joseph knows that as an American citizen he has more opportunities, but even today, as high school seniors like him prepare for their futures, his remains uncertain.

“I would be more relaxed, less afraid that something will happen to them, if they had TPS,” says Joseph.

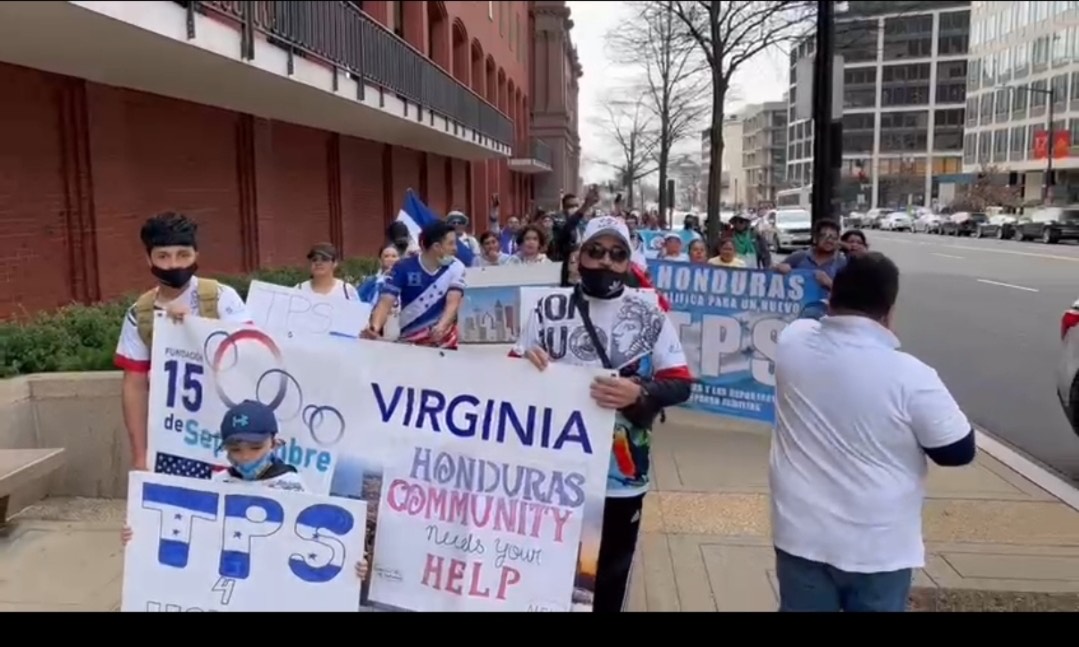

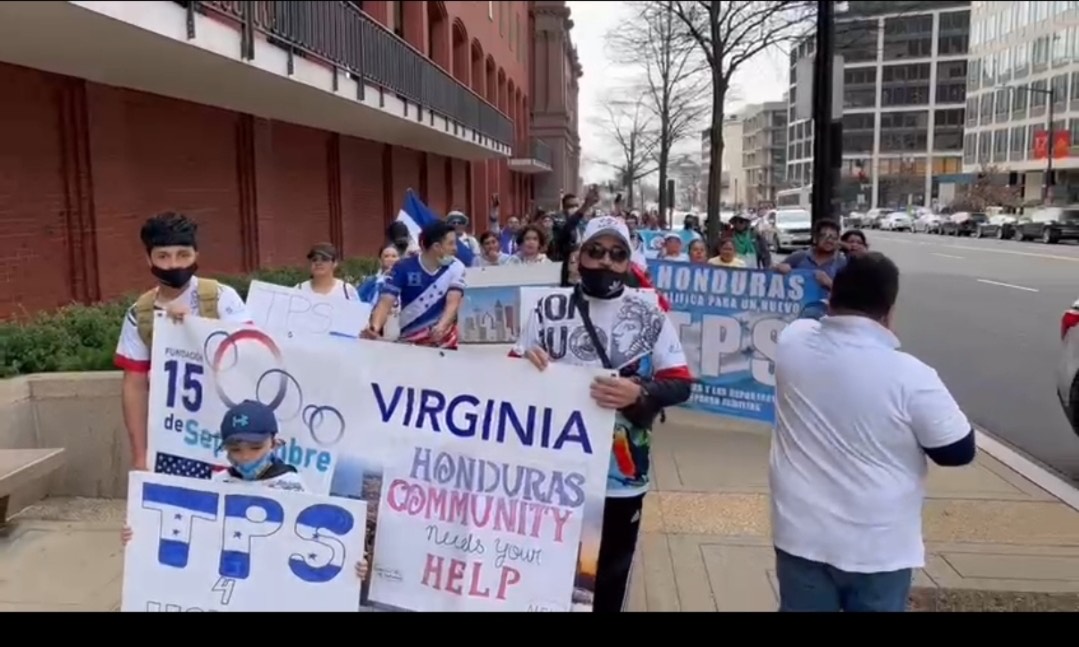

WASHINGTON, D.C., March 7, 2022 — I meet Faustino and Evelyn at separate protests for immigrants’ rights in front of the White House. Faustino stands facing Secret Service agents who pace along the fence that separates the throne of power from the park across the street. Joseph is there, holding the tiny hand of his little brother. They hold a sign asking for TPS, the Honduran flag draped over their shoulders.

It’s been two decades since Faustino and Evelyn left their lives behind in Central America. Both have been fighting to protect their families since they arrived.

“I would love for [the government] to take us into account,” says Evelyn. “The majority of us dream of a better life, a life we can’t have in our home countries. We want to move forward and help our families. We are hardworking people.”

Evelyn’s wish is to eventually gain citizenship and be able to show her kids where she grew up, and for them to meet relatives in person. Faustino similarly hopes he can gain citizenship one day, so that his kids never have to worry about him not coming home from work.

“Immigrants get too easily politicized, and promises are made, and President Biden has the ability to respond with executive action,” Faustino says. “TPS for the people that have been here for 20 years, or those that have American citizens in their families. People that have paid taxes and haven’t had problems with the law.”

“We are Americans,” he adds “I am an American.”

***

Ali Bianco is an immigration reporter working with the Medill News Service. She is a first-generation Venezuelan American and a student at Northwestern University. Twitter: @_alibianco

Honduras doesnt have the space in their schools to accomodate everyone going home??? but the US better have the space??? unbelievable