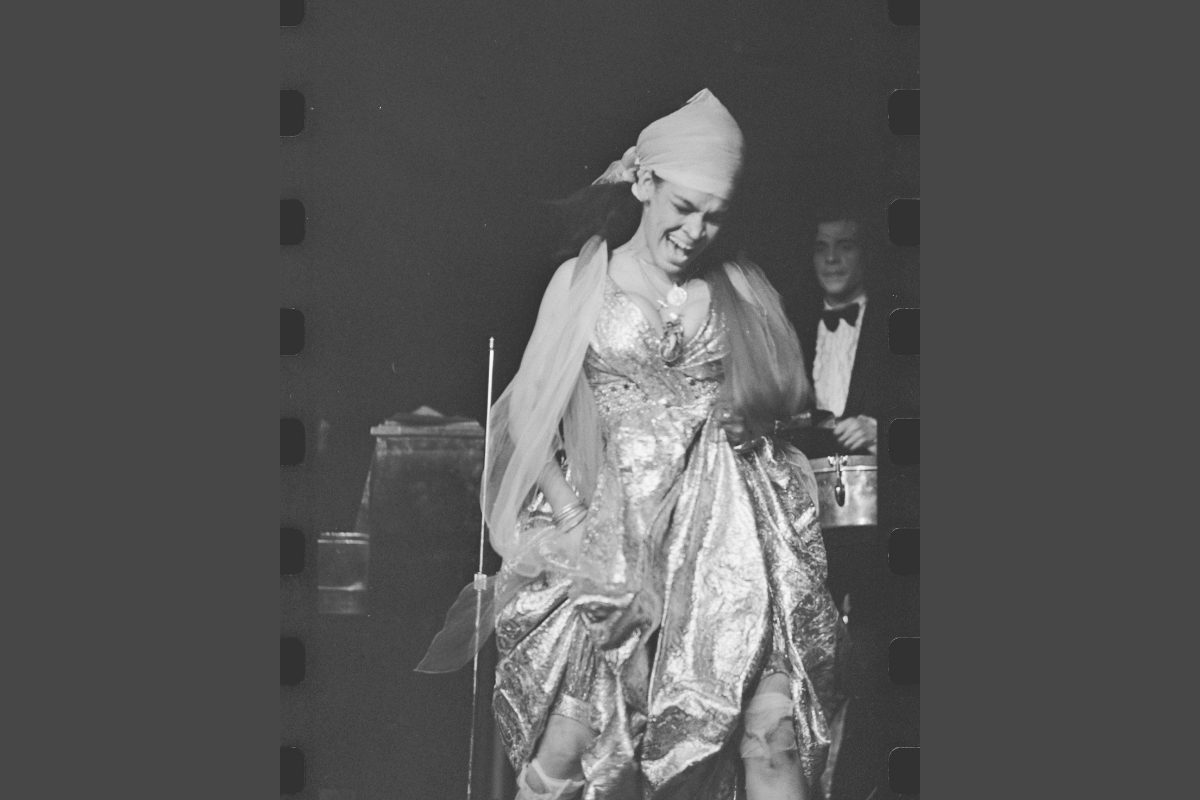

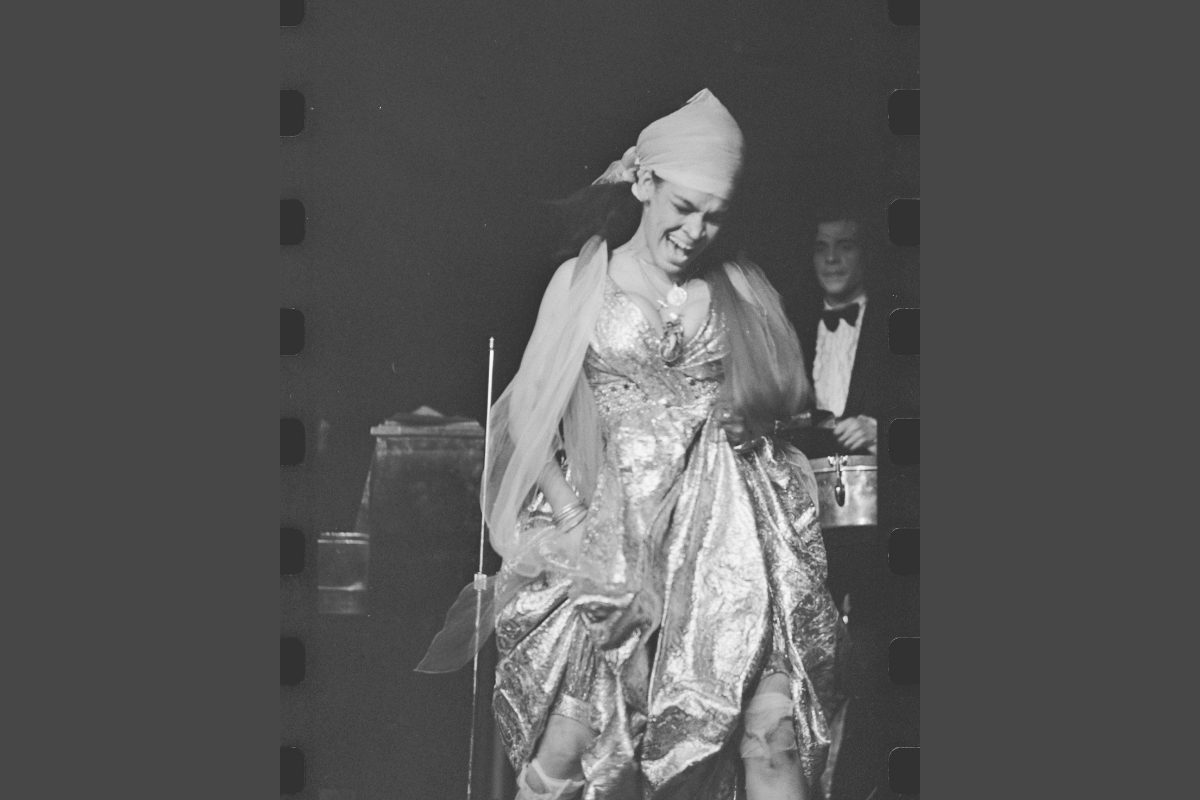

La Lupe (Public Domain)

Rainbow García stood on her old block in the Bronx, New York with bouquets of yellow roses and balloons. It was a few weeks after the 30th anniversary of her mother’s death, and Rainbow was making an ofrenda right on the street that’s named after her mother—La Lupe Way. Rainbow is the daughter of Lupe Victoria Yolí Raymond, or La Lupe— an Afro-Cuban singer who was once called the “Queen of Latin Soul.”

When Rainbow was growing up, La Lupe drove a station wagon and had a pet German Shepherd that would escort her down the block. But Rainbow said that even though her mother “wanted to be normal, she honestly stood out,” because she wasn’t just any neighbor: She was La Lupe, an inimitable artist whose performance style shocked audiences in the 1960s and 1970s. Rainbow said this part of the Bronx is a legend like her mother.

This episode of Latino USA is part of our series Genias in Music, remembering notable women and their contributions to their fields throughout history. In this installment, we question some of the myths about La Lupe that attempted to delegitimize her music and we look at how her identity as an Afro-Latina influenced the racist and sexist characterizations of her as “possessed,” “crazy” and “on drugs.” Scholars like Jadele McPherson and biographer Juan Moreno-Velázquez argue that La Lupe was misunderstood while she was alive because there was no one performing like her in the American and Latin mainstream. By singing and moving in the ways she was known for, La Lupe was resisting her erasure and claiming her space—whether audiences understood it or not.

La Lupe’s album covers portrayed her in metallic over-the-knee boots, mink coats, and petaled white skirts. She played at Carnegie Hall, headlined at Madison Square Garden and starred on Broadway. But before La Lupe became a legendary figure in New York, she was one of the top performers in Havana, Cuba in the late 1950s and early 60s, amid the Cuban Revolution. She was born in Santiago, on the eastern side of the island, which has one of the oldest comparsa or carnival traditions in Latin America.

La Lupe’s scream-like vocals and frenetic movements made her performances unpredictable—and unforgettable. Accounts of La Lupe’s act became like folklore in Cuba; onstage, she would moan, groan, shriek, kick off her shoes and pull her hair. As her radical stage persona became mythologized in Cuba, she threatened another revolutionary figure: Fidel Castro. By her account, Castro sent his officers to tell her that he wouldn’t share the spotlight. He censored her art, so La Lupe knew she had to leave the country.

When La Lupe arrived in New York City in the early 60s, she recorded with some of the biggest names in the Latin music scene, including percussionist Mongo Santamaría, with whom she recorded her first album in exile. She also met Tito Puente and they became friends and collaborators, recording multiple hits and albums, including the bolero “Qué Te Pedí.”

With artists like Puente, Santamaría and Johnny Pacheco, La Lupe was one of the only women performers helping solidify a Caribbean diasporic style in New York. And while she was known for boleros and boogaloo, she was also inspired by American genres like soul and rock, singing in both English and Spanish—often within the same song.

La Lupe was called “The Queen of Latin Soul,” both to promote her as a crossover artist, but also because she made soul music her own.

“She started to create musical arrangements that you could say are polyrhythmic and she’s putting them into sounds that you hear in R&B and pop music and soul music,” said Jadele McPherson, an artist-scholar who has studied performance and religion in Santiago de Cuba.

By the mid-70s, La Lupe’s label Tico Records was acquired by Fania, the “Motown of salsa.” With the salsa movement underway, Fania wasn’t as interested in La Lupe’s style and she was brushed aside while Celia Cruz was elevated. La Lupe earned the reputation of being difficult to manage and there were rumors that she was a drug abuser, even though her family and friends have consistently denied these claims. Changing tastes in Latin music coupled with her strained reputation led her career to decline by the 80s.

To her fans and Bronx community, La Lupe is an identity. Her pioneering legacy remains present through her music and memory, passed down to young generations of Latinos and Latinas who heard their families belt Lupe’s lyrics at barbecues and in their tías’ living rooms.

Featured image of La Lupe is part of the public domain.

Special thanks to Fulaso, whose track “No Mires” is featured in this episode.

***

Latino USA with Maria Hinojosa, produced by Futuro Media, is the longest-running Latino-focused program on U.S. public media.