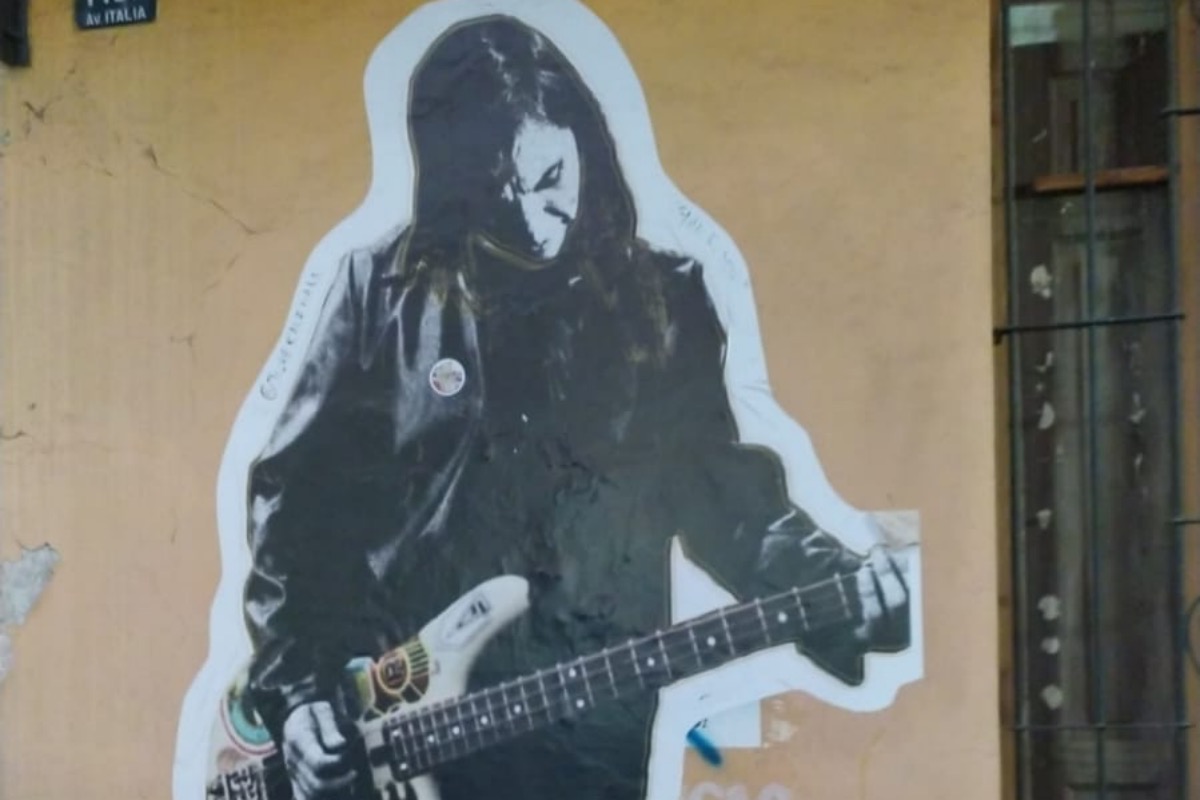

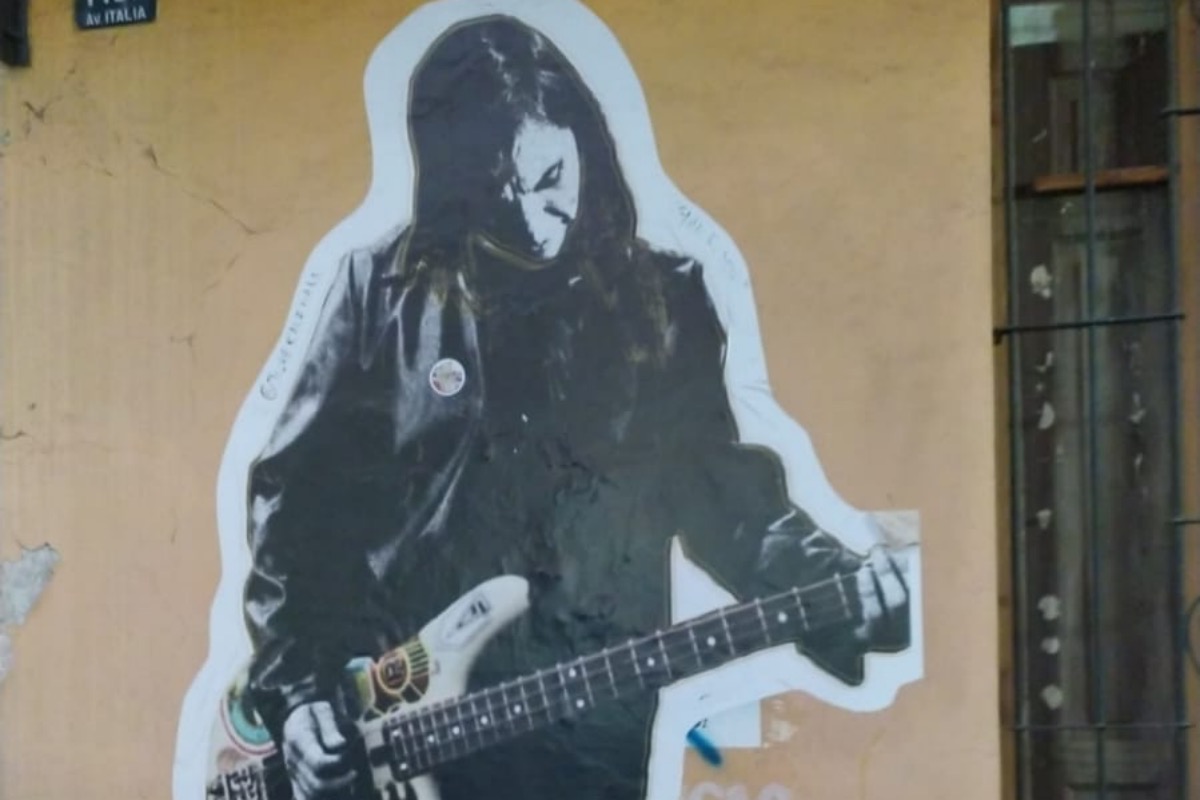

A stencil of singer-songwriter Violeta Parra as a punk rocker, seen on the streets of Chile today. (Nicolas Alonso)

By 1953, Violeta Parra had been playing music in Chile for more than 20 years. But at 35 years old, she began a mission that would change music in her country and beyond: to collect and preserve the country’s traditional folk music. Coming in contact with that musical heritage changed Violeta, and she would go on to compose song anthems like “Gracias a la vida,” which have touched people across the world. But life was not easy for Violeta—her life was marked by illness and loss.

In the latest episode of our Genias in Music series—about the lives and work of notable women musicians—we dive into the complexities of Violeta Parra, a pioneer of political folk music in Latin America.

Violeta was born in 1917 in a small village south of Santiago, the capital of Chile. She was the third of nine siblings—her father was a schoolteacher and her mother a seamstress. Behind her parents’ back, Violeta picked up the guitar and taught herself how to play when she was around seven years old. Her mother didn’t want any of her children to become musicians, but it was almost inevitable. After her father died of tuberculosis in 1930, the family couldn’t make ends meet so Violeta and three of the eldest children started going out to play in the streets and ask for food and money.

Violeta moved to Santiago a few years later and continued playing. She got married at 21, had two kids, and her career slowed down. Her husband wanted her to stay home and be with the children, which was expected of women at the time. But Violeta was never going to be just an ama de casa: she separated from that man and managed to have the marriage annulled —something virtually unheard of at the time in Chile— and continued her career playing in a duet with her older sister, Hilda Parra.

Violeta was restless. The biography Después de vivir un siglo, by Víctor Herrero, tells how one day in 1953, she went to visit her older brother Nicanor Parra—who would later become one of Chile’s most renowned poets. Nicanor was studying traditional forms of poetry, and Violeta recognized those forms as what the older generations sang in bars, music they had heard since they were children but was being lost. Nicanor encouraged her to find and preserve those traditional songs. Violeta threw herself completely into that work: she eventually collected more than 3,000 songs, folk tales, and proverbs. But she also wanted the whole world to know and appreciate the value of Chile’s traditional folk music.

That calling led her to accept an invitation to travel to Europe in 1955, even though her youngest daughter, Rosa Clara, was just nine months old at the time. Violeta left her daughter with her husband and said she would be back in two months. But tragically, Rosa Clara contracted pneumonia and passed away shortly after Violeta left. The singer-songwriter received the news when she arrived in Europe after a weeks-long boat trip. Devastated, Violeta turned to her work and decided to stay in Europe for almost two years.

When she returned to Chile, Violeta was already composing her own songs but she was also experimenting with new art forms. She began to paint, sculpt, and sew traditional large wool tapestries, called arpilleras. Her art would eventually make it to the Louvre museum.

Violeta’s music also grew experimental, recording instrumental albums that dabbled in atonal music. But Violeta didn’t stop collecting traditional folk music, and it enraged her to go out to the countryside and see how the poorest regions of Chile were left behind by the government. Her music also turned more overtly political, denouncing the hypocrisy of politicians and the Church, as well as the constant violence that the government inflicted on its own people.

By the 1960s, a new generation of musicians was playing folk music and popularizing it—among them Violeta’s eldest children, Isabel and Angel Parra. But Violeta felt she needed to go back to the roots and be closer to the people. So in 1965 she opened La Carpa de la Reina, a space where she wanted to build the “University of Folklore” and where anyone could learn to play, sing, and dance traditional folk music.

Sadly, that ambitious project would prove to be too much for Violeta. As she overextended herself to try to make it work, her physical and mental health started deteriorating. Sabine Berman, Violeta’s biographer, found that she had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder. It was during this time that Violeta would compose her masterpiece, the album Las últimas composiciones.

According to the scholar Paula Miranda, this album presents Violeta’s philosophy of life: love as an ethical principle with which to face the world. It’s what you hear in the anthem of gratitude “Gracias a la vida,” but also in “Volver a los 17,” and even a song like “Maldigo del alto cielo.” Violeta’s son has stated that with this album, Violeta said everything she needed to say in this life.

Soon after its publication, on February 5, 1967, Violeta ended her life. She didn’t get to see the changes that her music would bring in Chile, but she’s acknowledged as the “Mother of La Nueva Canción,” a movement of political folk music that swept Latin America in the coming years.

Violeta is acknowledged in Chile as the seed of political music. She’s seen as a rebel and a poet, a larger-than-life figure that gave Chile a musical identity. Her music and memory are alive to this day.

***

Latino USA with Maria Hinojosa, produced by Futuro Media, is the longest-running Latino-focused program on U.S. public media.