Armando Sandoval, leader of the Machetes, an offshoot of the Young Lords that advocated for Puerto Rican independence and served the community. Sandoval was shot in a drive-by on June 26, 1973, an event that sparked the Park Slope Riot. (Courtesy of Kima, Natalie, and Delmy Alina Sandoval)

On the evening of June 26, 1973, Elliot and Armando Sandoval were sitting on the front stoop of their first-floor apartment at 6 Berkeley Place in Park Slope, Brooklyn. It was late, brisk yet warm, like any other summer night. Quiet too.

Earlier that day, Puerto Rican candidate Herman Badillo lost to Abe Beame in the Democratic mayoral primary runoff election. Beame, who was white, won by a slim margin.

The race was about race—the actual politics were an afterthought. Tensions had been ratcheting up in the neighborhood following a string of racially motivated assaults on Black and Puerto Rican residents. Moreover, police brutality, domestic violence, and drug abuse were rampant not only in Park Slope but throughout New York City.

Seemingly out of nowhere, a sedan pulled up to where Elliot and Armando were relaxing. Armando had been chatting with an Italian friend when a group of armed Italian Park Slopers got out of the vehicle. It’s unclear whether a verbal exchange ensued —perhaps the Sandoval brothers were caught off guard— but before they could take cover, gunshots rang out.

Elliot was shot in the stomach and Armando took a bullet to the buttocks. As the assailants fled, one of gunmen shouted, “If Badillo had won, we would have killed you!”

The car peeled off, speeding down the dimly lit street and disappearing into the darkness. The Sandoval brothers were sent to New York-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital and weren’t discharged for at least a couple days.

Keeping Cool

The next day, “all hell broke loose,” according to Wilfred ‘Wilfie’ Sandoval, Armando’s brother and my mother’s uncle, who still vividly remembers what would become known as the Park Slope Riot of 1973.

Wilfie had taken the bus from Sunset Park to Park Slope along its usual route down 5th Avenue. He frequented the neighborhood to see his brothers. Wilfie grew up in Park Slope and remembers his childhood fondly.

After stepping off the bus, Wilfie started toward the apartment. It was a beautiful day. Everyone was outside. People seldom remained indoors during the summer. There was no air conditioning, no electric fans. All they had were cold showers and fire hydrants that children would set off so they could frolic. Keeping cool was somewhat of a challenge in Park Slope, both figuratively and literally—at least it was on June 27, 1973.

Wilfie noticed a crowd had gathered near 6 Berkeley Place. It was unusual, even for a community that spent most of its time outside. But word had quickly spread about the drive-by.

“Yo, the Italians, man, they shot your brothers. They shot your brother Armando. They shot your brother Elliot,” a Puerto Rican resident told Wilfie as he approached.

He was at a loss for words.

The rest is history.

The Park Slope Riot didn’t happen in a vacuum. Elliot had “put a gun to the Italians in the neighborhood and they retaliated,” Armando said online in 2015. “We had moved the mafia from our hood. They tried to bribe me, offering [part of] the numbers racket, which I turned down… we stood our ground.”

Presumably, the mafia approached Armando because of his role as the leader of the Machetes, an offshoot of the Young Lords that advocated for Puerto Rican independence and served the community however they could. This was a political organization, not a gang, though many of its members were packing.

Machete House

Armando founded the Machetes in response to widespread police brutality and domestic and racial violence that had been taking place throughout Park Slope at the time. The group sought to uplift the community.

Machete House, their headquarters, was located on the ground-level floor of 6 Berkeley Place. It was like a hotel. Anyone could crash there if there was enough room. There was a sofa and a single bunk bed with four mattresses built into it. If you were desperate, you could push some of the wooden chairs together and fall asleep in an upright position, though you might regret it the next morning.

According to Wilfie, the landlord forfeited the four-story property because he could no longer afford to maintain it. Tenants suddenly became squatters, and they continued living there for at least a few years. One of those squatters was Armando, who was also a factory worker at the time.

He had significant influence in the community. Armando was a radical who lamented terrorism and colonialism but adored Puerto Rican revolutionary Oscar López Rivera. When community members had issues that needed to be addressed, they typically didn’t go to the police—they went to the Sandovals.

Turning to the Machetes for help was commonplace. “Armando was a force to be reckoned with,” Wilfie told Latino Rebels. “But he had a heart of gold.”

At the time, Park Slope, specifically 5th Avenue, wasn’t the swanky spot it is today. It was an entirely different place before gentrifying forces had their way, indiscriminately displacing residents of all ethnic and racial backgrounds. By the start of the 1980s, developers hastily began forcing tenants out, ultimately erecting condominiums that now go for upwards of half a million dollars per unit.

Park Slope used to be a multicultural mosaic consisting of Puerto Ricans, Italians, Irish, West Indians, African Americans, and Russians. Although members of these ethnic groups could sometimes be found living in the same buildings with one another, the vast majority of Puerto Rican and Italian Park Slopers made their lives on opposite sides of 5th Avenue, which bisected the two communities.

“Tensions between these communities simmered along 5th Avenue; the intersection of 5th Avenue and Union Street was the epicenter of this tension; and Park Slope exploded in late June of 1973,” read a 2009 post on the blog Save the Slope.

It was more of an eruption.

‘All Hell Broke Loose’

“Everybody went home. Everybody got their guns,” Wilfie said. Strapped up and seriously pissed, some community members prepared for the worst.

If you ask Wilfie, he’ll tell you that the Puerto Ricans were defending themselves. Black and Puerto Rican Park Slopers were prone to being assaulted anytime they walked down President Street, the predominately Italian part of the neighborhood. When the Italians would pass through Berkeley Place or Sackett Street, they very rarely became victims of assault—and if they were, it wasn’t racialized.

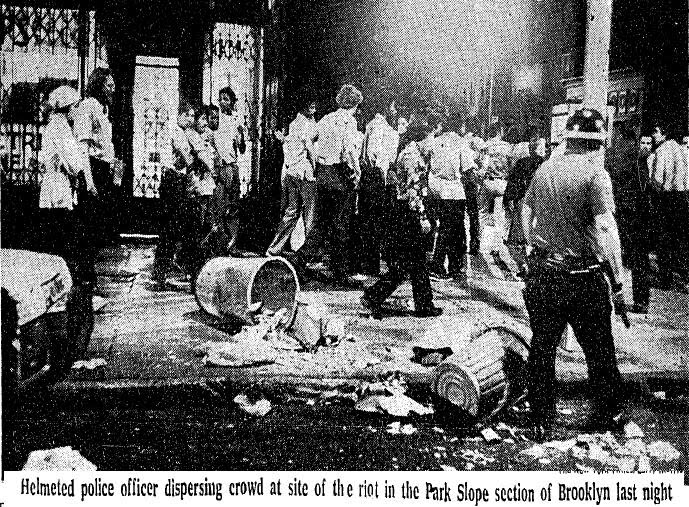

Darkness had fallen on the evening of June 27, 1973. Large crowds of Puerto Rican and Italian Park Slopers formed at the convergence of 5th Avenue and Union Street as cops from the New York City Police Department (NYPD) arrived at the scene. Cars and buses couldn’t get through. They were forced to take alternate routes.

Each police officer pulled up in a bright blue Plymouth Fury I, which had circular steel rims and extendable rooftop lights that illuminated the street. The soon-to-be rioters spewed racial epithets like “spick” and “guinea” before hurling bottles and bricks at each other.

Then came the firecrackers. There were hundreds of them. Trash cans were set ablaze. Car windows were smashed. Firebombs were hurled at cars.

Wilfie found himself in the middle of it all. As the chaos ensued, he heard what sounded like duct tape being ripped.

“That sound, man, it’s never left me,” he said. “A bullet breaking into the skin.”

Wilfie turned to see 15-year-old José Colón falling to the ground as blood gushed from his neck. A police officer dragged the still-bleeding teenager to safety as the Park Slopers exchanged gunfire. Colón had been shot by a .22 caliber sniper rifle and would become paralyzed from the neck down for the rest of his life. He died in 2004.

According to Save the Slope, the “wound was said to be a contributing factor in his death. The shooter, who had earlier served three years on a charge of reckless endangerment, was then charged with 2nd-degree murder, but ultimately pleaded guilty to a lesser charge of manslaughter in 2006 and was sentenced to two to six years.”

The riot turned into a shootout. Luckily, the Italians “were bad shots” or “a lot more people could have died,” Wiflie said.

The police officers who had arrived at the scene took cover by their cars and opted not to return fire. Eventually, the shooting died down.

“I guess everybody just got tired of it, you know?” Wilfie said.

At the end of the night, five people had been shot, including Colón, and five police officers sustained injuries.

History Repeating Itself

The Park Slope chapter of the Machetes disbanded in the early 1980s as drugs like heroin and crack ravaged impoverished communities across New York City. The “War on Drugs” saw New York’s finest attempt to arrest its way out of a public health crisis that continues into the present day, though the consensus is beginning to shift toward a harm reduction model.

I hardly knew my mother’s uncle Armando, who died of complications of COVID-19 in 2020. My deepest regret is not getting to know him when he was alive. He was an extraordinary man.

Armando wasn’t perfect. He was selfless and never backed down from a fight, including the struggle for Puerto Rican independence, a cause he supported until his passing. In 2015, he wrote: “I am still fighting for our country, which is Puerto Rico. We want to end US colonialism of our land.”

Puerto Rico remains far from obtaining the freedom it deserves. It is being gentrified, just like Brooklyn was in the late 20th century. Puerto Ricans are being pushed out. History is repeating itself.

The Revolutionary

At the time of the riot, Armando was 26 and thoroughly radicalized. His affinity for the Puerto Rican independence movement began long before the Machetes had even existed. As far as he could tell, Operation Bootstrap was a capitalist ploy to extract labor from a population that could be taken advantage of. But what other choice did people have?

Back in Puerto Rico, the Sandovals were incredibly impoverished. They lived in an overcrowded structure, working service jobs to make ends meet. Opportunities were scarce, so they migrated to the mainland over the course of several years to make a better life for themselves and their family.

In the United States they were poor too, yet they persisted. The American Dream was something they believed in.

But eventually Armando left the United States for Cuba and then Honduras. In Cuba, he worked in the sugarcane fields to survive. He saw similarities between Puerto Rico and Cuba. The two sister nations had been under the thumb of the United States since the Spanish-American War, both having traded Spanish colonialism for U.S. imperialism.

Puerto Rico remains a colony to this day. Cuba’s fate, though, was different: it became an independent communist state in 1959 following a revolution, a struggle that lasted roughly seven years. Armando went there for a reason. What did he hope to see? What did he learn?

He decided to move to Tegucigalpa, Honduras and started a family there. He would ultimately bring them to the United States. While living in Honduras, Armando served as armed security for schoolchildren. He would ride the bus with them to ensure their access to education.

“He wasn’t selfish. He was selfless,” Violeta Sandoval, Armando’s 14-year-old daughter, tells me. “He would rather feed someone else than feed himself.”

She describes her late father as a charismatic man who stood up for those around him.

Armando left behind a legacy of peace, love, and revolution. He fought for what was right, for the underserved, and for that, he lives beyond death now. Physical permeance is incapable of diluting the impact he had on the world and those around him.

Rest in power, Uncle Armando. You will be missed.

***

James Baratta is a freelance journalist graduating from Ithaca College in May 2022 with a B.A. in journalism. He has written for Common Dreams, Fairness & Accuracy In Reporting, and Truthout, among others. Twitter: @jamesjbaratta

so who lived there before the blacks and hispanics? werent they “pushed out”? white flight was wrong. whites moving in is wrong. well im pretty sure white people can live wherever they want. just like everyone else. maybe a committe should be formed and white people should just wait to be told where they can live. and thatll be a problem too. smh

[…] Source link […]