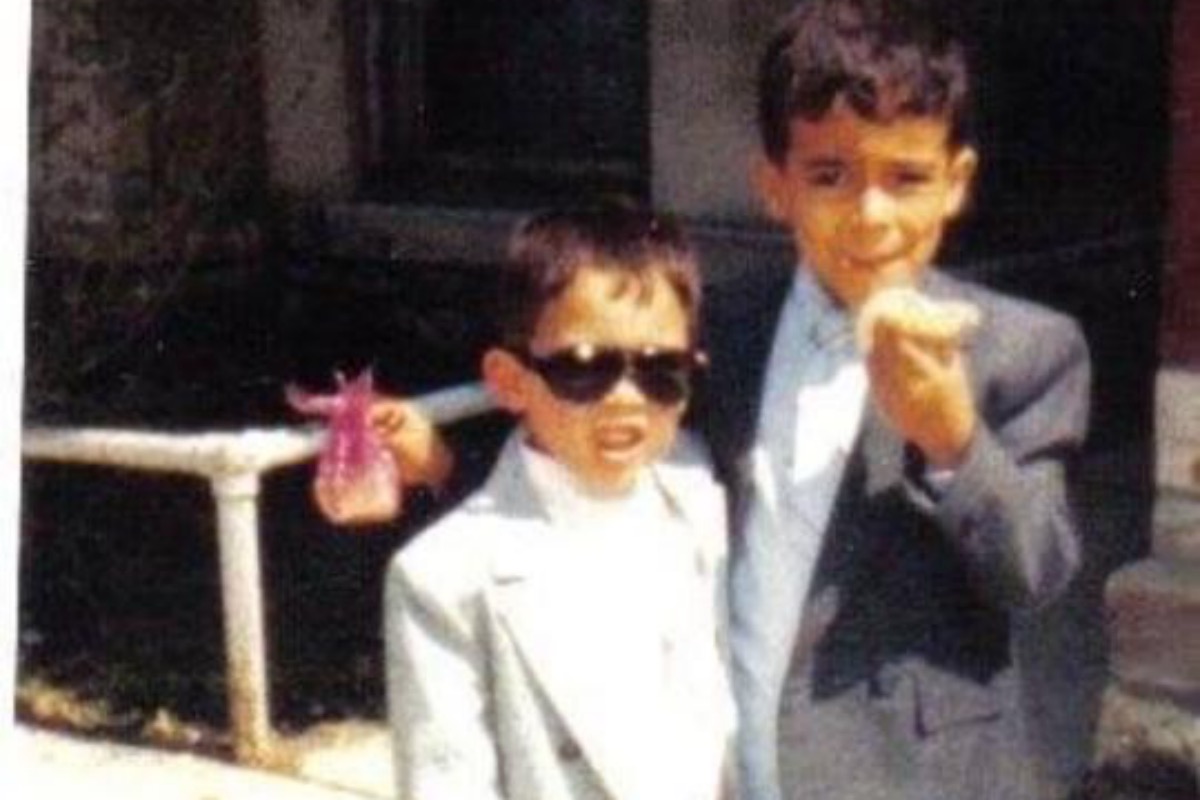

Hector Luis Alamo, right, with his brother Chris, Chicago, Illinois, c. 1990

LAS VEGAS — This story still stings, but I’ll tell it anyway.

It had been years since we saw my dad, at least three or four after my mom left him and moved us out to the burbs. Then he shows up one day wearing his police uniform.

Imagine a beige Puerto Rican man with a five o’clock shadow, thinning slicked-back hair, dark eyes, and broad shoulders, and you pretty much get the picture.

I was at home watching TV. I was no older than 11, still in elementary school. As usual, my little brother, who’s a year and three months younger than me, was out in the street, either playing basketball or setting shit on fire. My dad wanted to go looking for him.

We went to the school, checking the basketball courts along the way. My brother wasn’t at the courts or at school, but the front office lady told my old man about us missing days, and how my brother was getting C’s and D’s.

The way my dad told the lady “Oh yeah?” made my butt cheeks clench. He shot me the look.

We searched all around the neighborhood, my dad making me tell him where to look, but my brother was nowhere. So after half an hour or so, we headed back to the apartment.

We spotted my brother with his friends at the park inside our complex. My dad stopped the car right there, got out, pointed at my brother, and said, “YOU! Get your ass over here RIGHT NOW!”

My brother booked.

He was short for his age but he ran like a jackrabbit. And my dad was no chump either. He’d been in the Army, liked to work out, even played on the police softball team.

My brother ran all over the complex, cutting around buildings and racing across the lawns in between, my dad hot on his heels. My brother’s friends were watching the whole thing and cheering: “FUCKEN PIG! RUN CHRIS!”

They didn’t know our dad from Adam, had never seen him before. They thought some random cop was chasing my brother around, so they were rooting for the homie.

But my brother made a fatal error. A gamble, really, and it cost him. He ran into a building, trying to hide in a stairwell, and there my dad caught him.

When I saw them coming, my dad was gripping my brother by the upper arm, almost lifting him off the ground with one hand. There were tears and black fear in my brother’s eyes.

When we got inside the apartment —my mom wasn’t home— my dad, his eyes wild with rage, slowly slid off his thick police belt in one smooth motion, doubled it over, and chased my brother into the bedroom and went to town on him, growling threats as my brother cried and screamed with the crack of leather against his naked skin.

I was crouched in a corner of the sala with my hands on my ears bawling. When my dad was satisfied with my brother, he emerged from the room.

“You too,” he said with hate in his eyes.

I only got beat for a minute for missing so much school. Maybe my good grades saved me, but most likely the man had tired out on my brother.

My earliest memories of my dad back in Chicago are when my mom was in the Navy stationed at Gitmo, in Cuba, and we stayed with my dad and his Italian Beef wife —she wasn’t Italian Italian, feel me?— in a house near the Brickyard. I used to shit myself as a kid, don’t know why —guess I wasn’t properly potty-trained or something— and one time my dad beat the shit out of me for it.

“I’m doing this because I love you,” he said tenderly as he went to work on me.

I was in kindergarten, and even then it struck me as a weird thing for a father to tell his first-born son as he’s whipping him like a runaway slave. Part of me believed him, which made me glad that my dad loved me so much to pour that much energy into fixing me.

But another part of me —the bigger, growing part— knew that violence had nothing to do with love, that someone couldn’t possibly love me if they beat me, and that anyone who claimed to love me while beating me either didn’t know what love was or didn’t know how to love.

My dad was addicted to crack and other drugs, and had been since before I was born. I’m sure that’s part of what made him violent. I’ve also heard that his dad used to beat him, so there’s that too.

When he was sober and clean though, I tell you my dad was the greatest father on planet Earth. Everybody loved him, even my mom. He was funny and smart, the life of the party, the favorite son, favorite uncle, a good friend, the most popular among his cop buddies, liked by anyone who met him.

I was proud to be his son, proud that he had given me his own name. I used to think I had big shoes to fill.

But now that I’m a man —or as close as I’ve come to being one— I realize what my mom survived. I understand the familiar cold in her eyes, and why she eventually got violent with us—not that she was right, but I understand it. After all, my brother and I got violent with each other and other people.

Never with women though. That was one of the lines we drew early on that we hoped would keep us from becoming too much like our father.

The other, for me, was never doing any drug harder than Molly or shrooms.

I always assumed my mom was just a miserable person by nature, or that it had to do with her growing up a poor immigrant from Honduras. And since my father, when he was clean, was so upbeat and fun-loving, full of jokes, I resented my mom for the dark cloud that followed her around.

Now I know the agony she endured—for us. She sacrificed herself, letting herself get warped and dented, just to spare us the pain of living without the man we loved desperately.

My dad beat on my mom too, and since she had been in the Navy and was a bit of the G.I. Jane type, that wasn’t easy to do. She fought back plenty—punching, kicking, pulling, biting, scratching. But he was bigger than her and stronger and faster.

I remember when he cracked her with his power twister bar that he would bend over and over as we watched TV, usually Marty Stouffer’s Wild America or In Living Color. We were living in a ratty apartment in the old Wicker Park. My dad exploded and left my mom with a huge knot on the side of her forehead. For a whole week she looked like she was growing a horn.

One time, I forget what I did to deserve it, but my dad caught me while I was in the shower, knowing the belt would burn hotter against wet flesh.

My mom reported his violence and drug abuse to the police, but it was no use. They were all his friends down at the station, and a lot of them were drug addicts too who beat their wives and kids. It was just what they did, so complaining to them about my dad was like criticizing Chicagoans for eating deep-dish pizza.

But it’s been almost 30 years since all that, and my dad’s an old man now. I flew him out here to Vegas a few years back, before the pandemic, to spend time with me and my sister (it was her idea) and my brother and my niece. I remember being nervous as we were walking to meet him at baggage claim, like I was still afraid of him or something.

Then there he was, looking short and fragile and old. Don’t get me wrong, he looked good and strong for his age, even with the limp. But this clearly wasn’t the man I used to fear.

And I was no longer the boy who used to fear him.

We hadn’t seen him in almost 10 years, and it was weird how like us he was, or us him, I guess. Not only his face but the way he talked, the way he moved, his sense of humor.

The apple really doesn’t fall far from the tree, though I’d like to think I’ve rolled my ass a long way from where I fell.

To my dad’s credit, he had accepted our invitation to Vegas while expecting the worst. I could see it in his eyes. He was trying to be upbeat and play it cool, but dude was shitting himself.

I put a hand on his shoulder and said, “Don’t worry, old man. You’re not here to get bitched out. You’re safe.”

***

Hector Luis Alamo is the Senior Editor at Latino Rebels and hosts the Latin[ish] podcast. Twitter: @HectorLuisAlamo