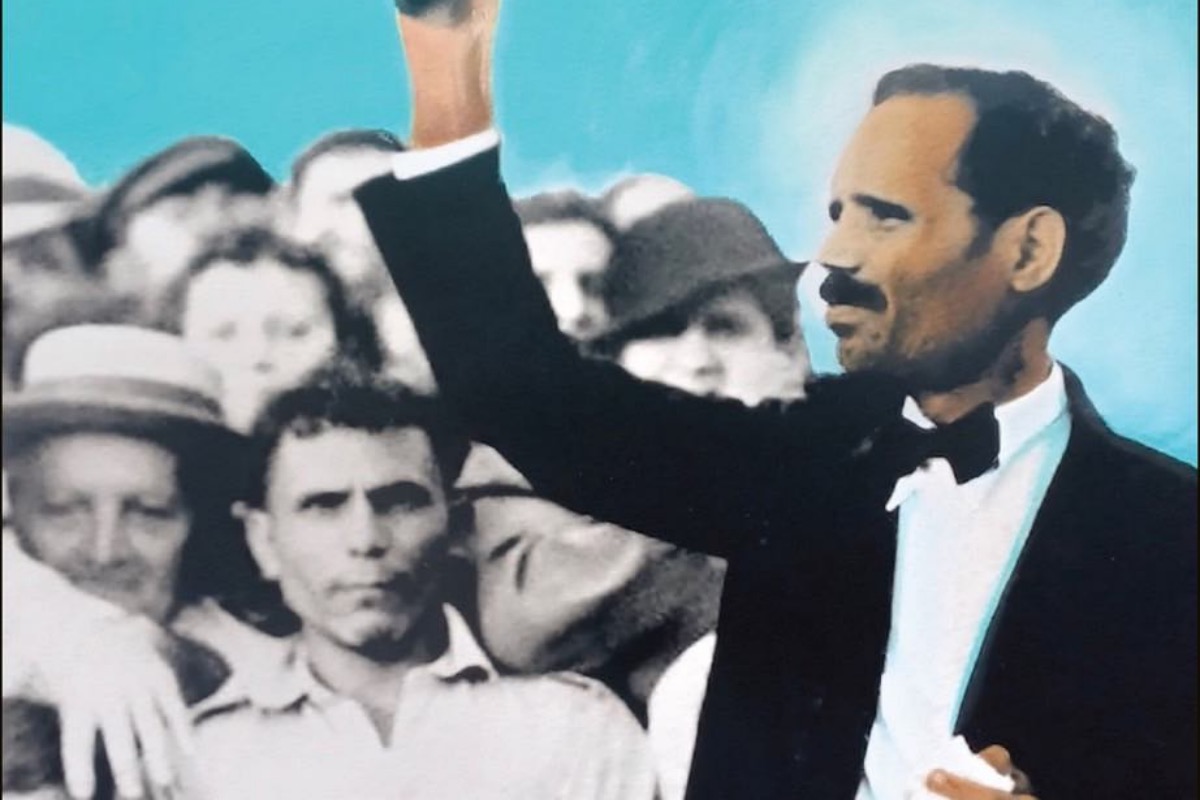

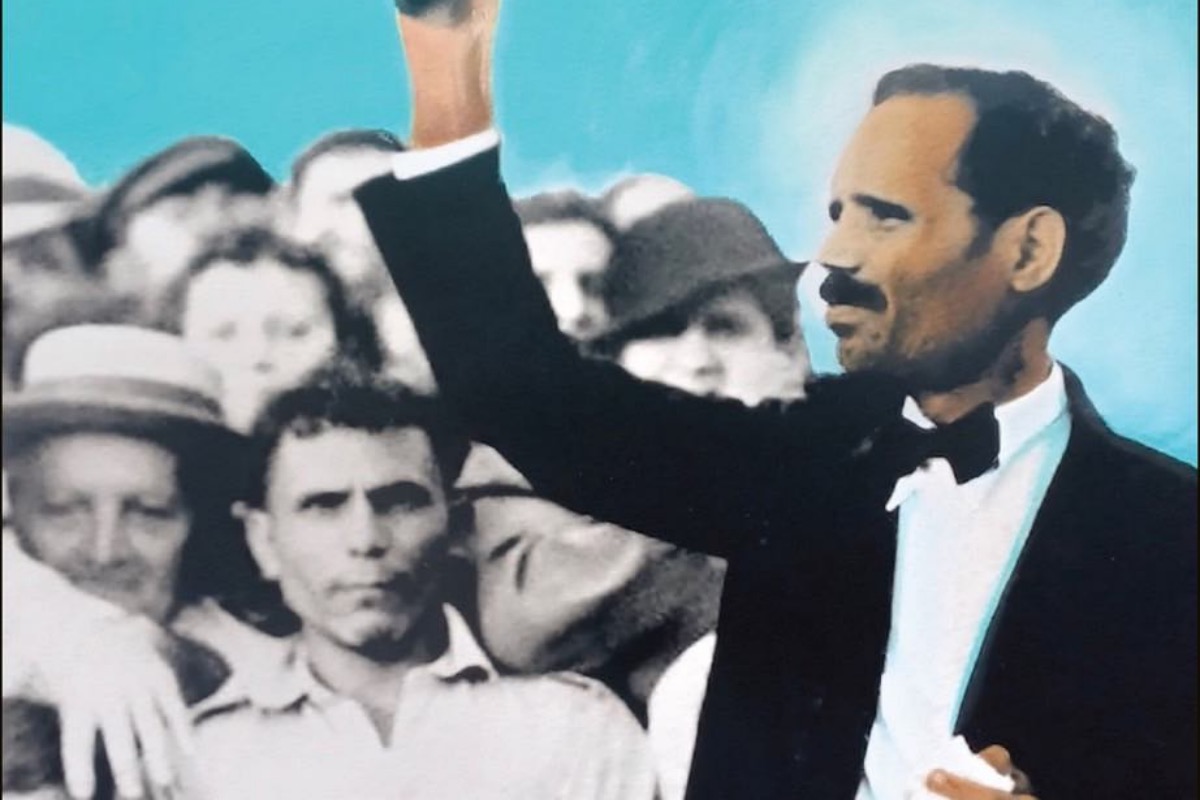

Cover art for ‘Vida y Hacienda: The Life and Legacy of Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos’ (Remembering Don Pedro/Facebook)

When I was completing the manuscript for my first book, Vida y Hacienda: The Life and Legacy of Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos, I knew that I wanted to tie the life’s work of Don Pedro, who transitioned to the ancestral realm in 1965, to contemporary Puerto Rico. Obviously, I knew that I had to at least consider 1) the fiscal control board, known as “La Junta,” created by an act of Congress in 2016 to steer the Puerto Rican economy through appointees of the U.S. president, and 2) the devastating, traumatic effects that Hurricane María has had on the Puerto Rican infrastructure and society since it struck in 2017.

I recalled something Don Pedro shared with Ruth Reynolds, a white U.S. anti-imperialist, which she later shared as part of her oral history conducted by the Center for Puerto Rican Studies in the 1980s:

“A few days after the devastating San Ciriaco Hurricane finished passing over Puerto Rico in 1899, a young Don Pedro overheard remarks given by an officer of the U.S. Army that impacted him so much he remembered and recounted them years later to her. Commenting on the effects of the hurricane, the officer called it a godsend, saying that the U.S. government could not have gained so much economic control in such a short time without it.”

As I point out in my book, the San Ciriaco hurricane struck in the early formative years of the U.S. colonial regime that was certainly opposed by sectors of the Puerto Rican people but that was not seriously challenged until 30 years later, when Don Pedro became president of the Nationalist Party of Puerto Rico in 1930.

Today, the socio-political climate has seen mass demonstrations that have forced a governor to resign his post, grassroots organizing that has both met immediate needs and put into question the efficacy of federal aid, and, more importantly, a renewed national dialogue around the status question —in response to status bills introduced on the floor of the U.S. Congress— as well as the very future of Puerto Rico itself, considering everything that has taken place over the past five years.

For Puerto Rico, Don Pedro represents an important link, a continuity, between the generations of the 19th century, when Latin America freed itself from Spanish colonialism, and the modern era, in which Latin America strives to protect itself from the insidious influence of U.S. imperialism. He is responsible for establishing the seminal position in Puerto Rico’s national memory of El Grito de Lares, Ramón Emeterio Betances, “La Borinqueña,” the flag, and more.

Beginning in 1930, and when it was outlawed and made illegal during the era of the Gag Law from 1948 to 1957, Don Pedro made symbols and icons out of this revolutionary history. So powerful and immovable were they that the commonwealth government which could not replace them, had to co-opt them instead in 1952, darkening the shade of blue in the flag and softening the revolutionary lyrics of the anthem.

Don Pedro matters because he represents a dream deferred. Puerto Rico has been a colony since 1493, when the Taíno and their Borikén leader, Agüeybaná, began to face the colonial ambition of imperial Spain. Don Pedro spoke of the right of Puerto Rico to take its place as a free nation within the international community, able to control its own destiny. He not only cited the moral obligation of the international community to support Puerto Rico’s national self-determination, he also argued for independence from the perspective of international law, saying that, since Puerto Rico had been granted autonomy by Spain in 1897 and was not consulted in the Treaty of Paris that ended the Spanish-American War in 1898, the U.S. occupation was illegal and to be resisted by all means.

From a scholarly perspective, there is still much to uncover and contextualize with respect to Don Pedro in particular and Puerto Rico’s independence movement in general. When it comes to the many documents belonging to Don Pedro and the Nationalist Party that were confiscated by the colonial or federal government through raids or other repressive means, there is no telling how much material will ultimately see the light of day.

In spite of this, researchers like José Manuel Dávila Marichal, who recently authored Pedro Albizu Campos y el Ejército Libertador del Partido Nacionalista de Puerto Rico (1930-1939), will have a key role in countering the narrative that has stigmatized and characterized as bearing no practical value the independence movement and its adherents.

The example I always give, as far as research that needs to be further expanded upon with regard to Don Pedro, is his effort in 1936 to hold a constitutional convention. Always encountering details about his trial under charges of seditious conspiracy, rarely do I see any attention given to his call for the political parties of Puerto Rico to elect delegates to meet in a constitutional convention, declare Puerto Rico an independent republic, and begin discussions over what they would later present to the United States as terms for a permanent treaty between the two nations.

As I discovered that there was not only support from the political leaders of Puerto Rico for this convention —including the leader of the statehood party at the time— but that there was also considerable popular support among the masses —before even a month had passed, more than 10,000 people took part in a pro-constitutional convention meeting in Caguas, and more than 30 municipalities saw the Puerto Rican flag raised in their respective town halls in support of the movement— I realized there is still so much research to be done.

Don Pedro matters because many still do not realize his impact and effectiveness.

Don Pedro matters because he is a prominent part of that historical narrative that has been suppressed and slandered. I do believe that, once Puerto Rico becomes a free nation, he will hold a much more honored place in history.

For now, Don Pedro’s stands as the inspiration for countless people to take up the fight for liberation from colonialism and the imperialist threat that casts a dark shadow over the Caribbean territory whose sovereignty has been usurped since 1493—the Puerto Rican archipelago, the nation of Borikén.

—

You can help the author raise funds for his next project, a book of translations of writings authored by Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos, by donating to and sharing his GoFundMe campaign.

***

Andre Lee Muniz is a Boricua from the projects of South Brooklyn, the creator of Remembering Don Pedro, and the author of ‘Vida y Hacienda: The Life and Legacy of Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos.’ Instagram: @RememberingDonPedro

[…] A new book on the legacy of Pedro Albizu Campos recently came out. The book is Vida y Hacienda: the Life and Legacy of Pedro Albizu Campos (link to the Big A, appears to be independently published. Not even WorldCat has a record). I learned about it via Latino Rebels. […]