Castillo San Felipe del Morro, known as El Morro and built by the Spanish Empire beginning in the 16th century, guards the entrance to San Juan Bay in Puerto Rico. The citadel was attacked by the U.S. Navy in May 1898 during the Spanish-American War. (Breezy Baldwin/CC BY 2.0)

The Puerto Ricans who support statehood always insist that the U.S. invasion was celebrated by the people of the island. What they fail to mention is that Gen. Miles and his 3300 soldiers were greeted as “liberators,” in quotes, not as mere substitutes for the Spanish colonizers.

The year before, 1897, Madrid had granted Puerto Rico some autonomy—more autonomy than it has now in some ways. The governor general was still appointed by the king, but he wasn’t allowed to stick his nose in the towns’ local affairs without special permission, and Puerto Rico was free to conduct its own trade with the United States and Europe’s other colonies in the Caribbean.

As it stands today, while the people of Puerto Rico are allowed to elect their own governor (since 1948), Puerto Rico doesn’t control its trade —not only that, but anything sailing in and out of Puerto Rican ports must be carried on U.S.-owned and operated ships— and the supreme power of the land, besides Washington, is a seven-member control board imposed by Congress, appointed by the president of the United States, and authorized to meddle in anything and everything that touches the budget or the colonial debt.

Its official name is the “Financial Oversight and Management Board for Puerto Rico” —notice the “for”— but it’s known by the people of Puerto Rico, perceptively simple as the masses everywhere tend to be, as “La Junta.”

As an American —growing up as an American, I mean— I always identified the word junta with the vicious little group of generals that took over a country after a coup, usually in Latin America, but sometimes in Asia or Africa too. So it’s surprising and depressing to see the United States impose its own junta in Latin America, and in the land of my grandparents no less. Instead of epaulets, orders of merit and insignias of rank though, the junta now running things in Puerto Rico, in true American style, wear suits and ties and call the shots from Washington with Wall Street constantly in their ears.

This can’t be what the Puerto Ricans had in mind when they welcomed the English-speaking soldiers in July 1898. Most of those who weren’t still groveling before Spain saw the landing at Guánica as the beginning of the end of almost 500 years of colonial rule.

Gen. Miles chose the spot at the last minute, en route from Cuba where the Spanish navy had just been whooped. He wanted the southwest corner of the island not only because it was the closest to his approach —having just sailed past the southern coast of the D.R. aboard the USS Yale, part of a convoy with 12 other ships— but because the newspapers back home had blabbed too about the original plan to land at Cabo San Juan near Fajardo, on the far side of the island, and then march on San Juan some 47 miles away with a full force of 15,000-something men.

This was the plan, devised and approved by President McKinley and the secretary of war (which is what the Defense Department called itself in the days when America still had no empire to defend). Hearing the news, the Spanish fortified the northern and eastern parts of the island, which were already very pro-Spain.

Had Gen. Miles gone ahead as planned, the invasion might’ve been the bloodiest in U.S. history before the D-Day landing at Normandy during the Second World War. The quick thinking by Miles probably saved a lot of lives and shortened the campaign in Puerto Rico.

Nelson Miles, Commanding General of the U.S. Army, 1898 (Public Domain)

If the name “Nelson Miles” doesn’t ring a bell, he’s the guy Washington sent to the frontier after the Civil War to create a safe space for white people and greed.

“It was Miles who had driven Sitting Bull into Canada after the Battle of the Little Big Horn, Miles who captured Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, and Miles who had put down the Ghost Dance disturbance that ended with the battle of Wounded Knee in 1890,” writes C. Douglas Sterner in A Splendid Little War. “Though the massacre at Wounded Knee badly damaged General Miles’s reputation, he was promoted to Major General and in 1895 became the Commanding General of the Army”—the last man to hold that powerful title before it was replaced by the diluted role of Army chief of staff.

Miles was a bad man, for better and worse. His name stands in the annals of U.S. military history alongside those of Gens. Washington, Scott, Grant, Sherman, Custer, Pershing —who fought at San Juan Hill in Cuba a few weeks before the invasion of Puerto Rico— Patton, Eisenhower, and MacArthur. Miles’ name has largely been forgotten for two reasons: first, because while the other generals (except Custer) are viewed as having fought for just or honorable causes, Miles fought for mostly racist and imperialistic ones; and second, because unlike Custer, who finally got what was coming to him, Miles died an old man.

That’s how America atones for its crimes: not by apologizing or making reparations, but by forgetting.

I’m giving you this little background on Miles so you know the kind of man that was leading the liberators of Puerto Rico in 1898, and just what kind of liberation they brought.

Americans watching the general’s movements from back home must’ve known what he had in mind as he eyed the coast of Puerto Rico in late July. During the debates in Congress leading up to the declaration of war against Spain in April, a group of senators led by Republican Henry Teller from Colorado made America promise it wouldn’t hold onto Cuba after liberating her, but would help her become independent as quickly as possible.

Why the Teller Amendment didn’t include Puerto Rico, the Philippines, or any of the other islands that the U.S. ultimately took possession of as the prizes of war, I have no idea. I’m thinking it was just a clumsy oversight. Maybe Teller and them assumed that what they said about Cuba would apply to all of the Spanish colonies America invaded. Or maybe they just couldn’t imagine that Puerto Rico and the others would be made colonies of the United States, much less for over a century and counting.

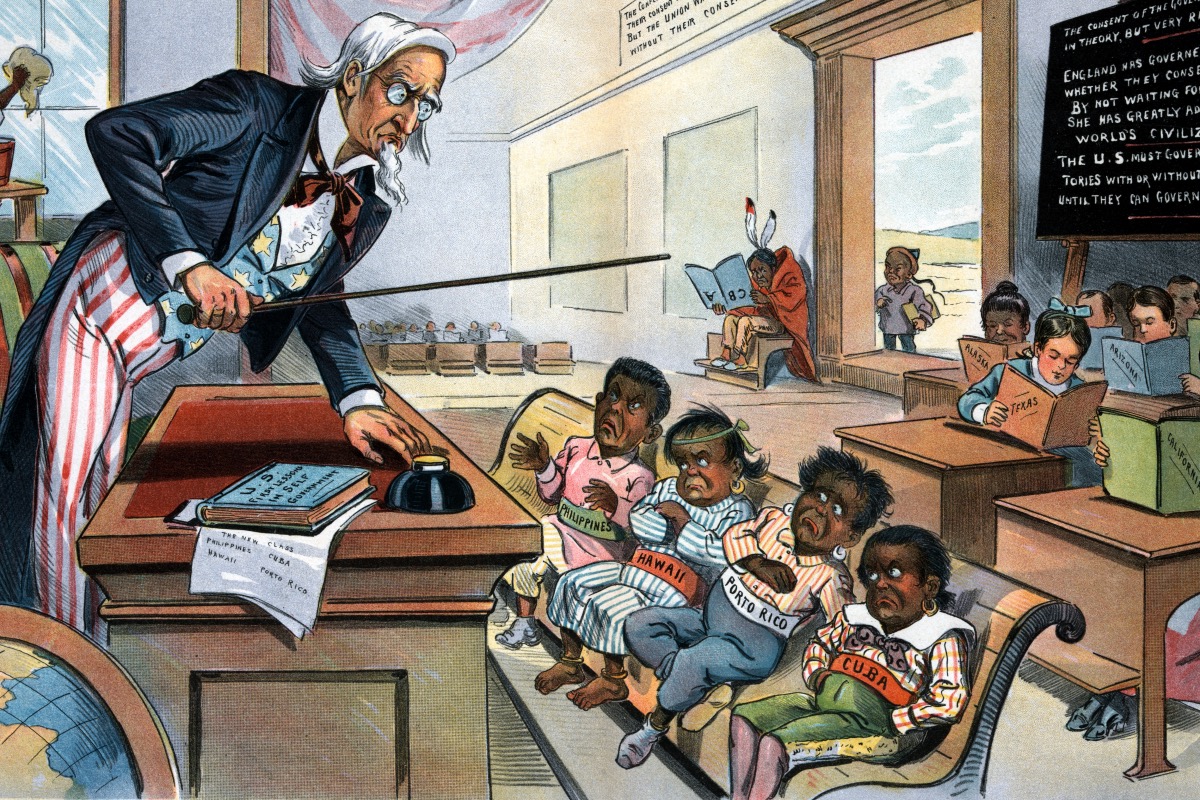

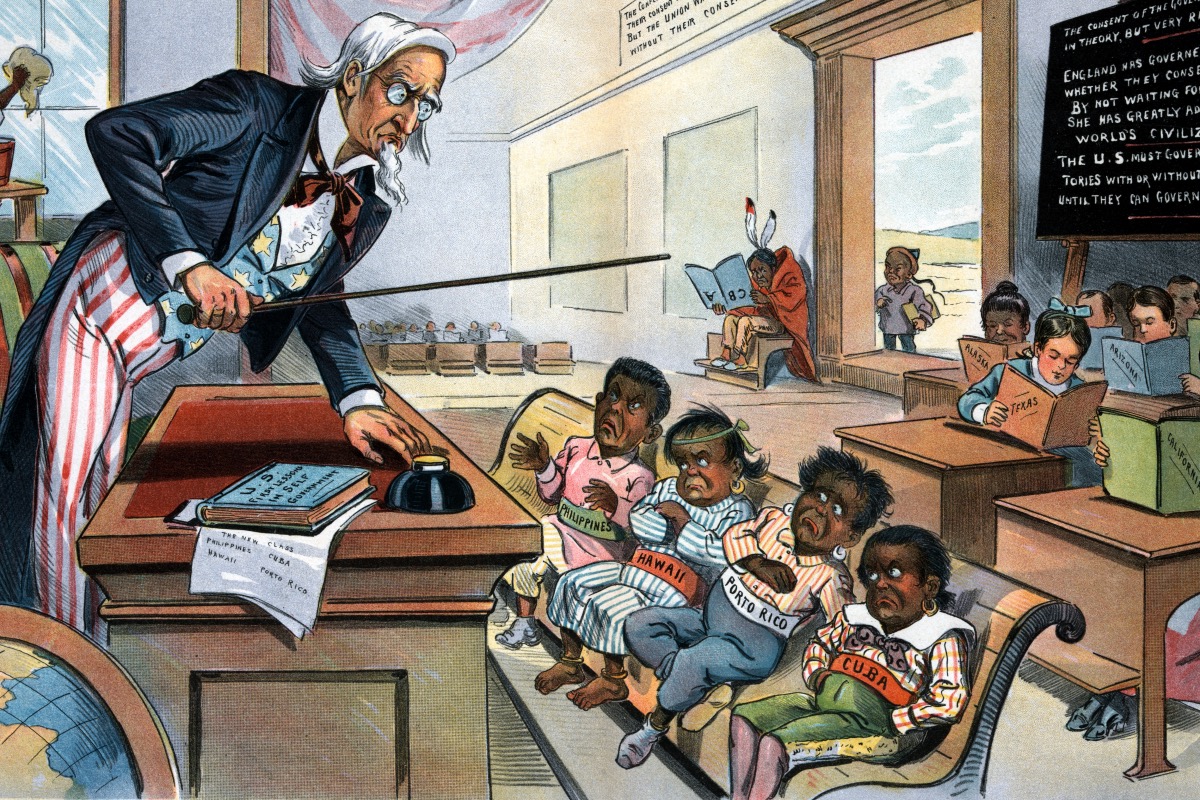

Caricature by Louis Dalrymple shows Uncle Sam lecturing four children — labeled Philippines, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and Cuba — in front of children holding books labeled with various U.S. states. A Black boy is washing windows, a Native American sits separate from the class, and a Chinese boy is outside the door. The caption reads: “School Begins. Uncle Sam (to his new class in Civilization): ‘Now, children, you’ve got to learn these lessons whether you want to or not! But just take a look at the class ahead of you, and remember that, in a little while, you will feel as glad to be here as they are!'” (Public Domain)

A month before the invasion of Puerto Rico, the American Anti-Imperialist League had met for the first time in Boston. The group counted among its members the activist and social worker Jane Addams, steel baron Andrew Carnegie, former Presidents Benjamin Harrison and Gover Cleveland, author Henry James and his philosopher brother William, labor leader Sam Gompers, and arguably the most famous man in the world at the time, Mark Twain, just to name a few of the characters whose names we still mention today.

Their anti-imperialism was founded on the principle that “all men, of whatever race or color, are entitled to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” as they later wrote in their 1899 platform. They held as their guiding documents the Declaration of Independence, Washington’s Farewell Address, and Lincoln’s powerful words at Gettysburg and other places.

“We maintain that governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed,” the League said. “We insist that the subjugation of any people is ‘criminal aggression’ and open disloyalty to the distinctive principles of our government.”

“It should, it seems to me, be our pleasure and duty to make those people free, and let them deal with their own domestic questions in their own way,” wrote Twain of Spain’s former colonial subjects in the Philippines in 1900, who had declared their independence two years before but were fighting a brutal war against their supposed American liberators.

“And so I am an anti-imperialist,” said Twain. “I am opposed to having the eagle put its talons on any other land.”

Just as Twain and others condemned the idea of the United States owning colonies, Puerto Ricans had been arguing and fighting against Spanish colonial rule —or colonial rule of any kind— in Puerto Rico. The Grito de Lares, which had seen Puerto Rico become an independent republic for a few fleeting hours, had occurred just 30 years before the invasion, and was followed by pro-independence stirrings across the archipelago, leading to another failed uprising, this time in Yauco, only a year before and a few miles from where the U.S. stepped ashore.

The charter granting autonomy came a few months after the Intentona de Yauco—“the Attempt,” as it’s called. So, fact is, Gen. Miles and his men might not have received such a warm welcome were it not for Gov. Macías y Casado in San Juan suspending the new autonomous government and declaring martial law right after the declaration of war in April.

Many of the same people who took part in the Grito de Lares and the later uprising in Yauco really did celebrate the arrival of Yankee soldiers, thinking the land of Lincoln and Jefferson had come to spread the blessings of liberty in Puerto Rico and help her stand on her own, as was Washington’s stated goal in neighboring Cuba. Hostos himself hoped so. De Diego, now called the “Father of the Puerto Rican Independence Movement” but still a 32-year-old poet at the time who had been a vice minister in the short-lived autonomous government, thought the invasion would mean equal U.S. citizenship rights for Puerto Ricans, a dream he was promptly snapped out of by the racist policies instituted by the ensuing military occupation.

General Nelson Miles and other soldiers on horseback in Puerto Rico in 1898 (Public Domain)

Gen. Miles, slick as he was, may have understood the political climate in Puerto Rico better than the physical.

“From all contemporary accounts,” writes Dr. Mark R. Barnes, senior archeologist with the National Park Service, “the Puerto Rican population were in the main not unwilling to accept the American troops, but Miles knew it was psychologically and strategically prudent to not give them any excuse to initiate local resistance to his forces. For this reason, American troops were kept under strict control to prevent any outrages against the civilian population and Puerto Rico guides and translators who accompanied all the American units provided good communication with the islanders. In addition, the influx of American money to hire Puerto Rican stevedores, oxen cart drivers, laundresses, and a host of other service providers gave a boost to the economy of the southern part of the island.”

Barnes quotes a New York Times article dated July 27, two days after the invasion:

“The neighborhood of Guanica and Ponce is said to be the section of the island where the opposition to Spanish rule is strongest and where a propaganda campaign in favor of accepting the Americans as deliverers (emphasis mine) instead of as enemies could be most advantageously begun. Gen. Miles has with him some representatives of the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Junta. It is believed that one of his objects in touching near Ponce is to establish contact with the insurgent and set on foot a movement which may result in making the American occupation of the island much easier than it would be if all the efforts of the invaders were confined to fighting their way along. General Miles had a number of conferences with representatives of the revolutionists of the island before he left here, and he is known to have counted on doing as much toward winning over the people of the province by friendly overtures as possible, having regard to the ultimate benefits of such a policy on the permanent American rule, which it is proposed to establish here.”

Why would an American general meeting with Puerto Rican revolutionaries before his invasion of Puerto Rico give anyone the impression that he was going there to help it secure its independence?

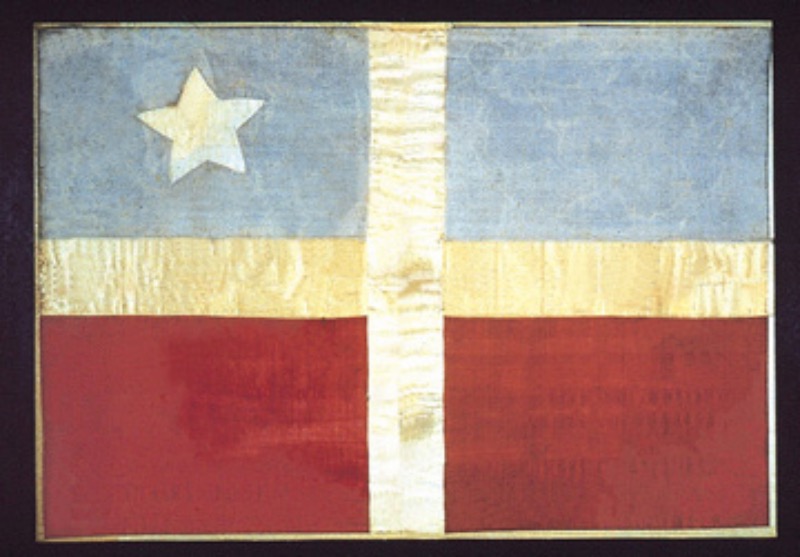

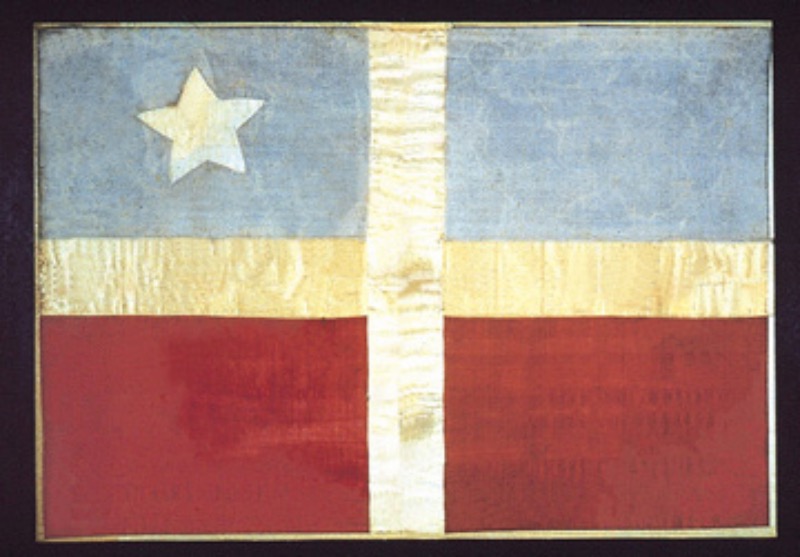

The “Revolutionary Junta” mentioned refers to, I assume, the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico, first founded by Betances and others in the Dominican Republic in 1867 for the purposes of planning what would become the Grito de Lares the year after, and later refounded in New York in 1895, where it would plan the uprising in Yauco and design the first modern-day version of the Puerto Rican flag. (It’s often said that the Gag Law of 1948 made it illegal to display the Puerto Rican flag in Puerto Rico, or even own one. But the legislature in San Juan only criminalized what had already been a federal offense in Puerto Rico since the occupation began in 1898.)

The original flag of El Grito de Lares, also known as “The First Puerto Rican Flag” (Museum of History, Anthropology and Art/University of Puerto Rico/CC BY 3.0)

Much is made of the reception Gen. Miles received from the local leaders of Ponce, who held a banquet to honor the invaders after they reached the city —the largest on the island at the time— where Miles would set up his headquarters. The welcoming committee was headed by Rosendo Matienzo Cintrón, an outspoken member of the Puerto Rican Autonomist Party. He and the party had been pushing for full independence within the Spanish Empire—something like the Free Association status in relation to the United States that some Puerto Ricans are calling for today, under which Puerto Rico would be free, but protected.

Gen. Miles, knowing he had to play his cards right or risk having to fight both the Spaniards looking to keep their colony and the Puerto Ricans looking to free themselves from outside control, gave a speech to the assembled ponceños that disguised America’s plans for Puerto Rico.

“In the prosecution of war against the kingdom of Spain by the people of the United States,” he said, “in the cause of liberty, justice, and humanity, its military forces have come to occupy the island of Puerto Rico. They come bearing the banner of freedom.”

Maybe no other man embodies the spirit of Puerto Rico before, during, and after the invasion better than Matienzo Cintrón, who heard Gen. Miles speak that day in Ponce. An autonomist when the Americans landed, a year later he joined the newly founded pro-statehood party, the Partido Republicano Puertorriqueño, believing U.S. statehood was more or less in line with his autonomist goals, only replacing Madrid with Washington.

Quickly realizing this wouldn’t be the case, he broke with the statehooders, forming the Unionist Party in 1904 alongside de Diego and Luis Muñoz Rivera, both of whom had been founding members of the Autonomist Party. The Unionists controlled Puerto Rican politics till 1932, and were the first major party to advocate openly for the independence of Puerto Rico.

With Muñoz Rivera as Puerto Rico’s resident commissioner in Washington and de Diego as president of the Puerto Rican House of Delegates —the highest elected office in Puerto Rico at the time, as the governor was still appointed by the White House— Puerto Rico voted various times for independence or at least greater sovereignty in the early days of the occupation.

Everything got shot down or nipped in the bud by Washington.

The year before he died in 1913, Matienzo Cintrón broke with the Unionist Party, feeling it wasn’t doing enough to push for Puerto Rico’s independence. He formed the Puerto Rican Independence Party with Luis Lloréns Torres and others, and together they wrote a manifesto demanding Puerto Rico’s full and immediate independence.

When the United States threatened to grant citizenship to the people of Puerto Rico in 1916 —as a way of smothering the cries for independence while scoring a supply of dark bodies to chuck at the Germans over in Europe— Muñoz Rivera, still the resident commissioner in Washington, gave a speech on Capitol Hill basically telling the Americans “thanks, but no thanks.”

“Our natural citizenship,” he said, is “founded not on the conventionalism of law but on the fact that we were born on an island and love that island above all else, and would not exchange our country for any other country, though it were one as great and as free as the United States. If Puerto Rico were to disappear in a geological catastrophe and there survived a thousand or 10,000 or a hundred thousand Puerto Ricans, and they were given their choice of all citizenships of the world, they would choose without a moment’s hesitation that of the United States. But so long as Puerto Rico exists on the surface of the ocean, poor and small as she is, and even if she were poorer or smaller, Puerto Ricans will always choose Puerto Rican citizenship.

“It is true,” he admitted, “that my countrymen have asked many times, unanimously, for American citizenship. They asked for it when through the promise of General Miles on his disembarkation in Ponce… they believe it not only possible but probable, not only probable but certain, that American citizenship was the door by which to enter, not after a period of 100 years nor of 10, but immediately into the fellowship of American people as a State of the Union. Today they no longer believe it.”

“Give us our independence,” he ended, “and you will stand before humanity as the greatest of the great.”

He spoke these words in May 1916, and died in November.

Since even before his death though, from the moment Gen. Miles landed on that doomed beach, there has been a steady campaign to snuff out any patriotic feeling or cravings for freedom in Puerto Rico. The Law of 1948, which for nine years made it illegal to even whistle a pro-Puerto Rico tune, much less have a get-together and talk about independence, is but one of an endless string of attempts to kill Puerto Rico’s spirit.

The multiple arrests and imprisonments of Albizu Campos and other members of the Nationalist Party…

The Ponce Massacre…

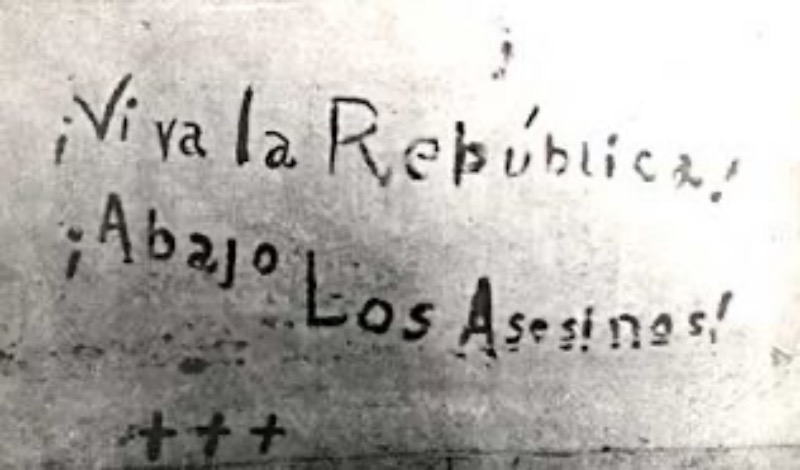

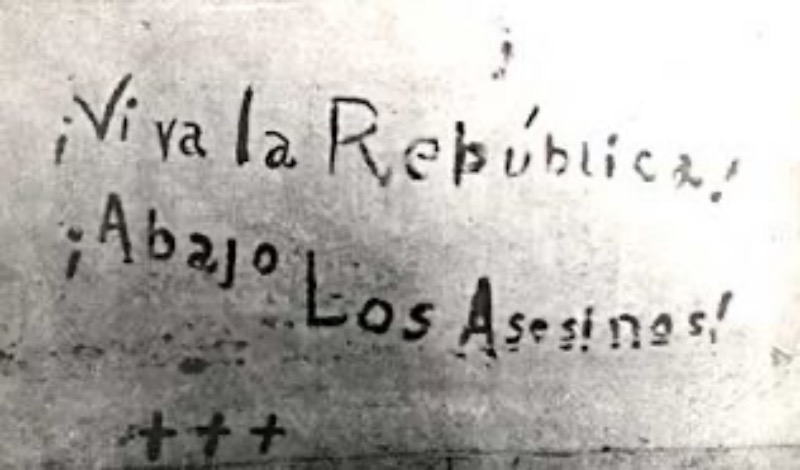

Message written during the Ponce Massacre by young Nationalist cadet Bolívar Márquez Telechea with his own blood before he died, which reads: “Long live the Republic, Down with the Murderers!” March 21, 1937 (Public Domain)

The bombing of Utuado and Jayuya by the U.S. Air Force during Puerto Rico’s third major attempt to free itself…

The murder of pro-independence activists at Cerro Maravilla in 1978, on the anniversary of the invasion, which by then had gone from being known as “Occupation Day” to “Constitution Day”—being the same day that Muñoz Rivera’s son, Puerto Rico’s first elected governor and its greatest traitor, signed the U.S.-approved Constitution of Puerto Rico in 1952, giving birth to its current “Commonwealth” status…

The imprisonment of members of the Fuerzas Armadas de Liberación Nacional, including the 36 years dealt to Oscar López Rivera…

The persecution of FALN’s successor, the Macheteros, and the murder of its leader Filiberto Ojeda Ríos by federal agents at his home in 2005—and on the anniversary of the Grito de Lares too…

The decades-long hunt for those last two groups is deemed justified since their actions are what propagandists for America call “terrorism.”

Tar-and-feathering royal officers, as the Patriots did in the lead-up to the American Revolutionary War; pouring scalding hot tea down the throats of tax collectors just doing their jobs; causing millions of dollars in damages and losses by dumping crates of tea into Boston Harbor—none of that’s deemed terrorism because it was done for America.

The Confederate generals and their soldiers, who waged war against the United States, are not remembered as enemies. They get statues and schools named in their honor.

But any Puerto Rican who dares lift a finger, or even their voice, in defense of Puerto Rico’s natural right to run itself fully and completely, without a foreign veto, has been treated as if they were criminally insane or a plague-carrying rat.

So it’s no wonder then that Puerto Rican independence doesn’t enjoy much public support these days. Or why a day like the 10th of December, the day on which the Treaty of Paris was signed in 1898, ending the war between Spain and the United States, and transferring ownership of Puerto Rico, Cuba, the Philippines, and other Spanish colonies over to the United States —the negotiations for which never including a single Puerto Rican, Cuban, or Filippino— can come and go without even a whisper.

***

Hector Luis Alamo is the Senior Editor at Latino Rebels and hosts the Latin[ish] podcast. Twitter: @HectorLuisAlamo