Illustration by Mya Pagán/Futuro Investigates

By ROXANNE SCOTT

During the winter, the two-family house I share with my mother sometimes gets so cold that I need a portable heater to stay warm. These days I use an electrical one. When I was a child, my family would turn the oven on to use it as a source of heat.

Now I’m aware that using a gas oven to keep warm can put tenants at risk for carbon monoxide. That made me wonder: How many people know the risks they face in their own homes from CO poisoning?

Until recently, my knowledge of carbon monoxide poisoning was limited to cases where people died at home in their sleep. During the past months, I’ve been following and analyzing the coverage of leaks.

Usually, it would be a quick news spot about the leak on the radio or TV, and maybe assurances that the family or people have been evacuated.

At times, an incident rises to national attention, such as the fatal leak in an Ohio apartment due to a defective boiler, the leak at a daycare in Pennsylvania, or the recent deaths of travelers staying in AirBnbs in Mexico.

And then the coverage disappears.

In New York City, a tenant typically makes a 311 complaint for an immediate housing hazard such as a lack of heat or hot water. According to housing advocates, the lack of a carbon monoxide detector isn’t exactly top of mind when it comes to filing a housing complaint.

“But that could be a representation of the fact that people don’t know that this is something that landlords are required to provide and that they could really benefit from it,” said Sateesh Nori, executive director of JustFix, a housing justice organization that helps renters organize against landlords, including assisting residents in filing a letter of complaint.

Housing advocates say landlords not making much-needed repairs continues the legacy of racism in housing. Because of government policies such as segregation and redlining as well as decades of disinvestment by financial institutions in Black and Latino neighborhoods, poor housing conditions are more likely to exist in these areas.

Latino and Black renters, regardless of income, make up the highest percentage of tenants with three or more maintenance deficiencies that can affect their health, according to public data.

Those deficiencies include rodents, mold, broken elevators, and heating issues.

Mildred Hernandez lives in The Bronx in a studio apartment with her three cats, Clara, Bella, and Kitty Hernandez, and a baby Chihuahua, Coco. She said she has dozens of problems in her apartment, including it getting too cold in the winter. Hernandez said she’s called 311 to file complaints for violations but would rather not go that route.

“You get tired dealing and dealing with the harassment from the landlord and the super,” she said.

Hernandez added that her landlord wants to push her out of the apartment.

“Whatever deficiencies are in place, a lot of times people don’t know what their rights are to safety,” said Milton Perez of VOCAL-NY, an organization that works on various social justice issues, including homelessness.

Since 2004, landlords in New York City have been mandated by law to provide and install at least one approved and operational carbon monoxide detector within each dwelling unit.

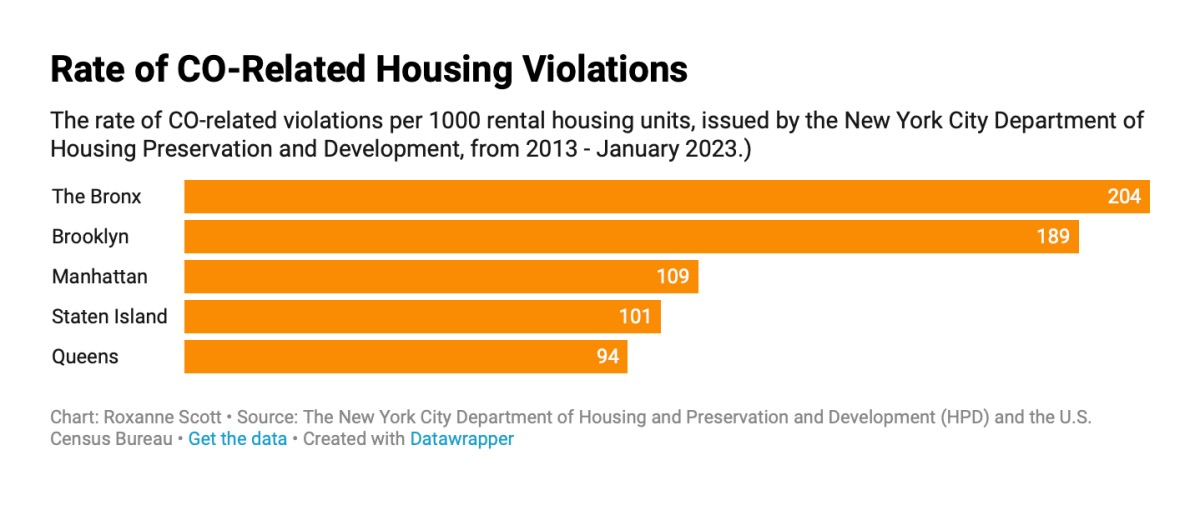

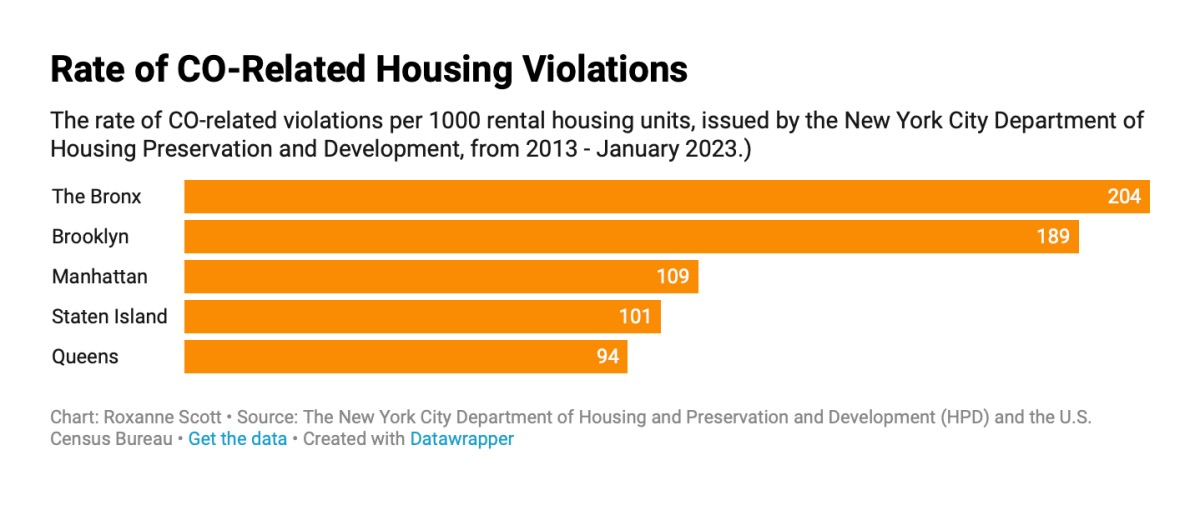

A data analysis by Futuro Investigates using housing violation and census data, found that the highest rate of carbon monoxide-related housing violations occurs in the Bronx, followed by Brooklyn and Manhattan.

It’s not that detectors are hard to come by; they can be easily purchased anywhere from hardware shops, big box retail stores, or online for as little as $25. And because people spend more than 90 percent of their time inside, knowing indoor air quality hazards could be a matter of life or death.

Here’s what you need to know about carbon monoxide poisoning and how detectors may be able to keep you safe in your home.

What Is Carbon Monoxide?

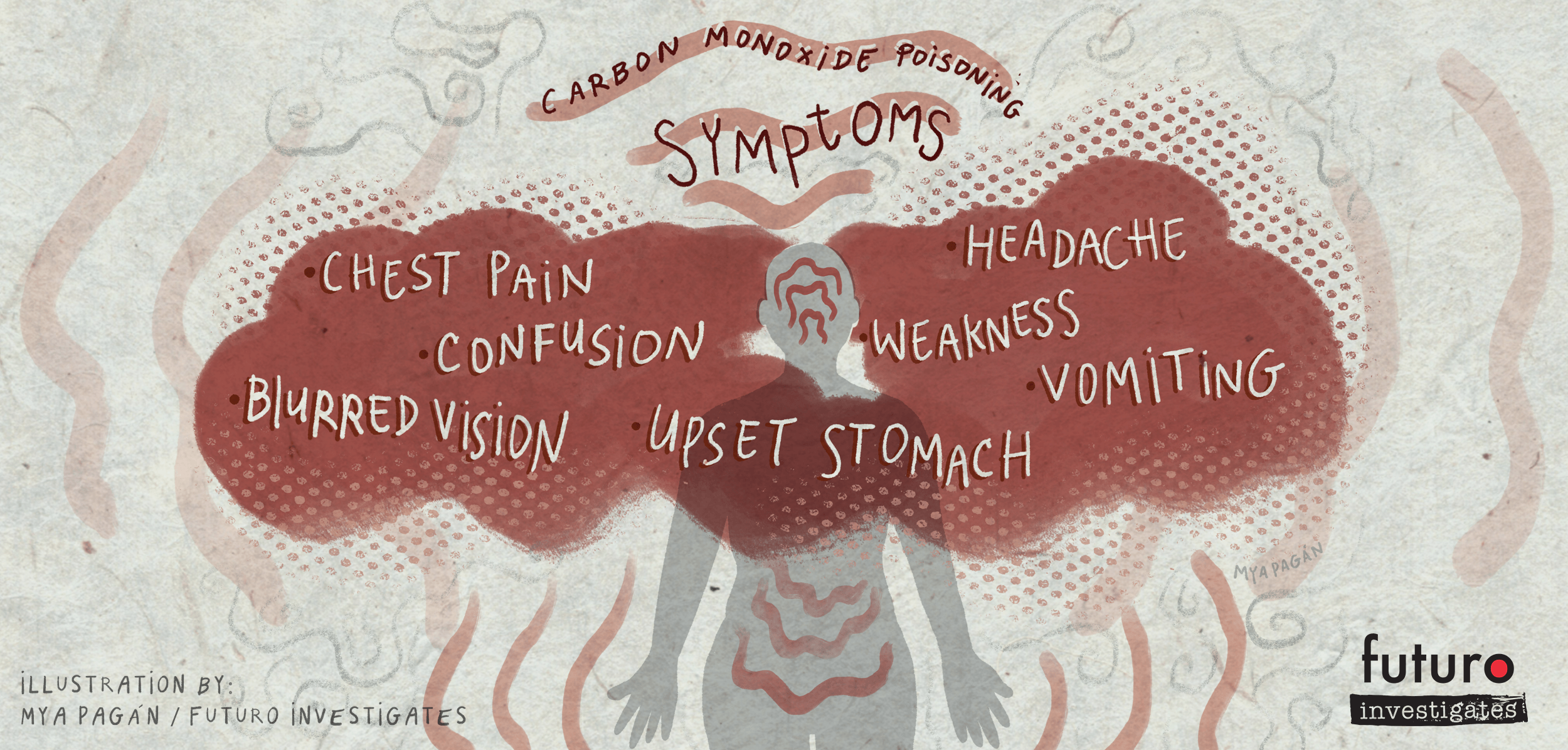

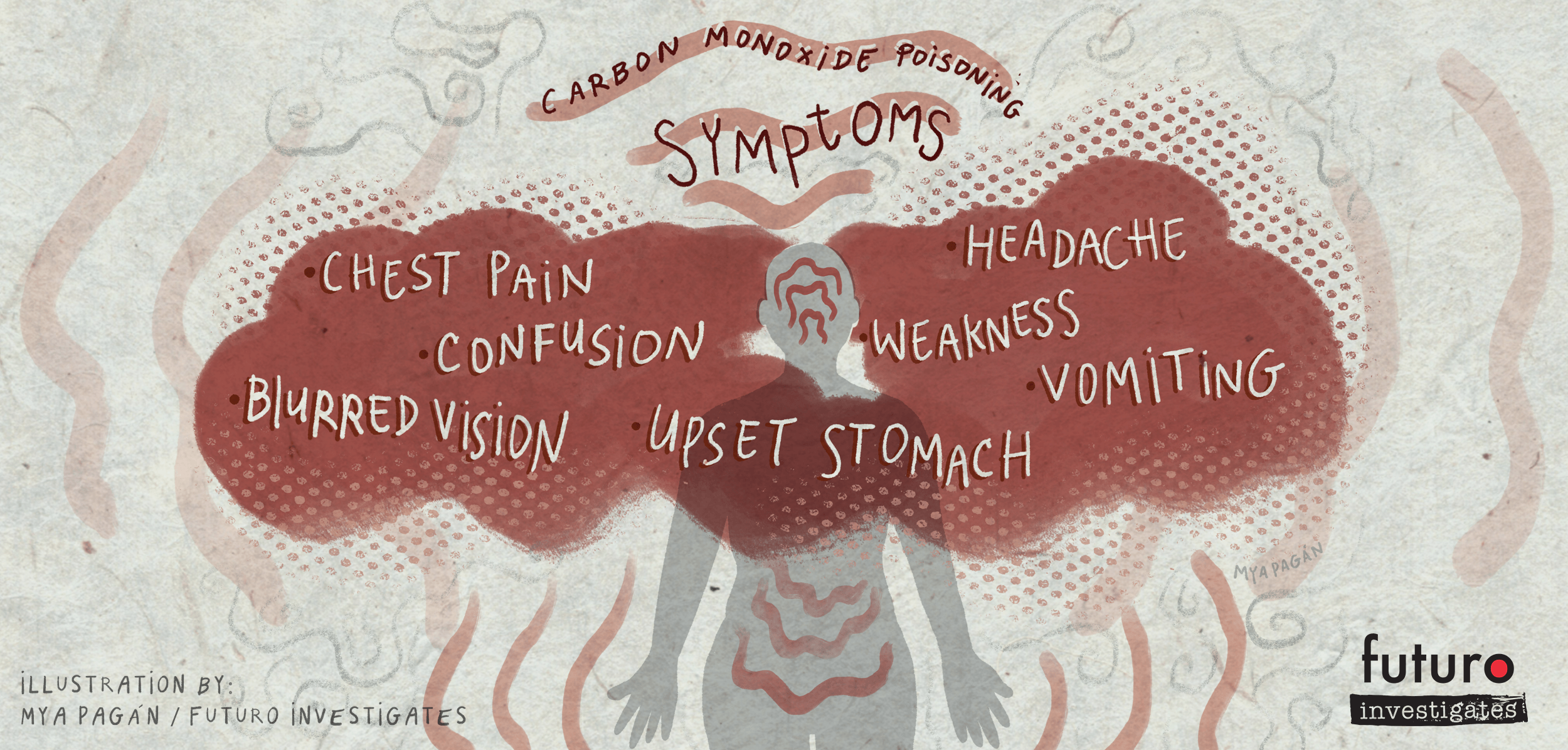

Often monikered “The Silent Killer,” the odorless and colorless gas causes symptoms such as dizziness, headaches and nausea. But those symptoms can be attributed to several maladies.

For this reason, the invisible gas is also referred to as “The Great Imitator.” People affected may very well think that they have the flu or food poisoning and can often be misdiagnosed when they go to a doctor.

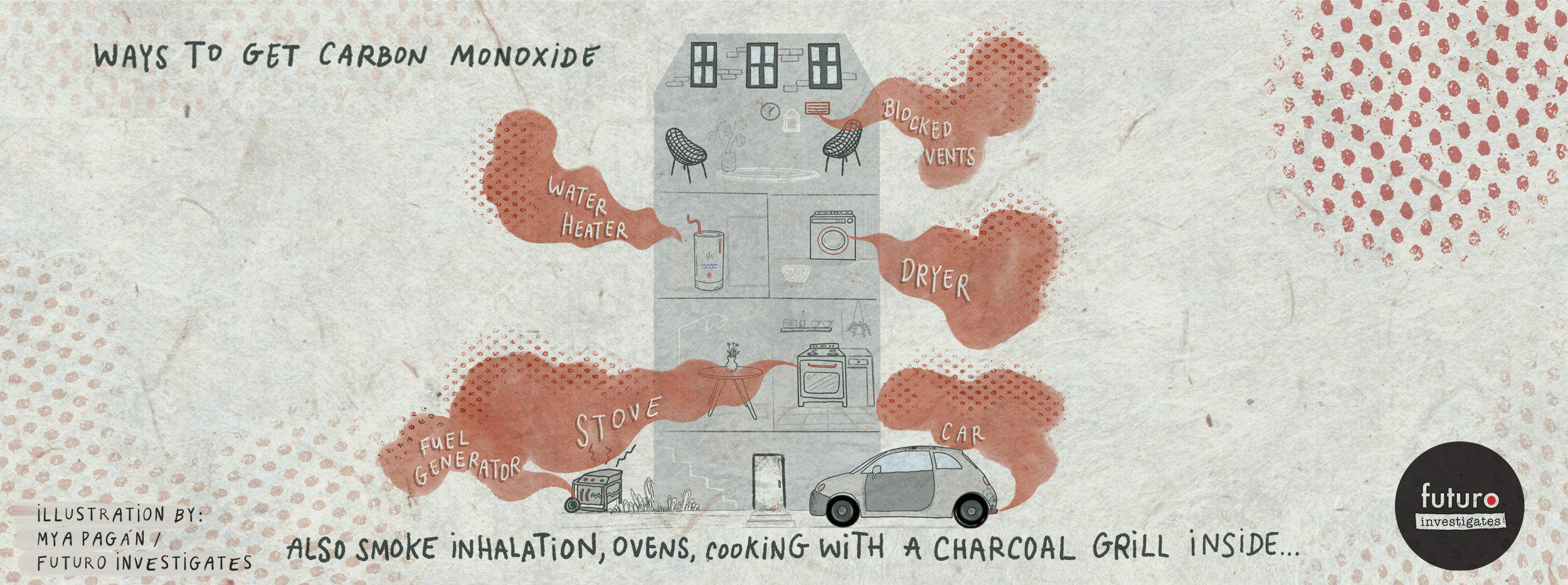

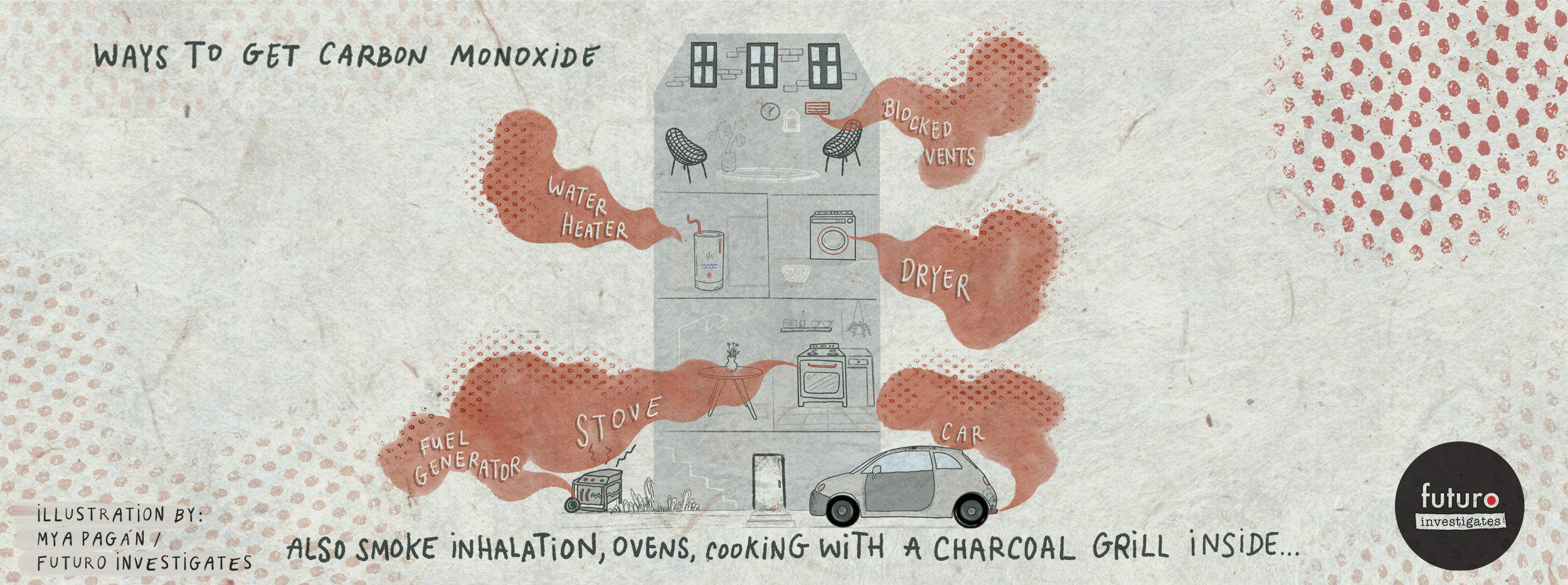

As the CDC publicizes, a source of carbon monoxide is idle cars in enclosed garages. In the home, carbon monoxide poisoning can come from a myriad of sources including ovens, faulty heating systems, and fuel-burning appliances.

Small amounts of carbon monoxide are also emitted from gas stoves daily, but defective stoves can release it at high levels.

During power outages due to severe weather, carbon monoxide poisoning can also come from fumes from portable generators.

A U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission report shows that Black people are at higher risk of CO poisoning due to generators, accounting for nearly a quarter of CO deaths.

Latinos of any race accounted for nearly 15 percent of these deaths. According to the commission, between 2011 and 2021 at least 770 people died in the U.S. of carbon monoxide poisoning while using portable generators.

What Does Carbon Monoxide Poisoning Look like?

When a person breathes in carbon monoxide, the gas replaces oxygen in the blood. At high levels, the gas can be fatal.

Without visual or olfactory clues like fire, a person may be in need of medical attention long before they’re overcome with carbon monoxide poisoning. Studies by the CDC warn that infants, children, pregnant women, the elderly and people with certain chronic conditions are particularly vulnerable to the gas.

At least 400 people across the U.S. die every year from poisoning and more than 100,000 visit the emergency room because of the gas, according to the CDC. Those cases include poisoning on boats and at work.

However, most poisoning happens in the home. The New York State Department of Health has counted nearly 900 deaths from carbon monoxide poisoning between 2000 and 2019.

In reality, carbon monoxide at low levels is all around us outside. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency monitors outdoor carbon monoxide and other common air pollutants. Indoors, however, depending on the local government, the gas is regulated by a hodgepodge of local housing agencies, health departments and/or fire departments.

Nikolas Petesic treats people with severe carbon monoxide poisoning at NYC Health + Hospitals/Jacobi in the Bronx. He works in a unit with a hyperbaric chamber, a nearly 25-foot submarine-shaped device that heals patients with severe poisoning.

Inside the chamber, patients breathe oxygen at higher than average air pressure to fill their blood with oxygen and reverse the effects of poisoning.

The nearly 25-foot hyperbaric chamber at NYC Health + Hospitals/Jacobi in the Bronx. The pressurized chamber treats people with severe carbon monoxide poisoning as well as decompression sickness from scuba diving. According to NYC Health + Hospitals, Jacobi performs about 1300 hyperbaric treatments per year. (Roxanne Scott/Futuro Investigates)

During the winter and times of natural disasters, Petesic sees an uptick in cases. “The extreme weather always brings patients to us,” he said.

Petesic remembers, for example, when his unit worked non-stop during the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy in 2012. The CDC said that more than 260 people were exposed to CO within the eight days after the storm made landfall.

During the Texas winter storm in 2021, The Texas Tribune reported at least 11 confirmed deaths with more than 1400 people seeking emergency care for carbon monoxide poisoning.

There’s also fire-related carbon monoxide poisoning. Petesic said medical staff worked day and night in 2022 after the Twin Parks fire in the Bronx, which killed 17 people.

The fire, the city’s deadliest in decades, was started by a defective space heater in the 19-story building. Many of the tenants were immigrants from The Gambia.

“Our team was here for basically 24 hours working on patients and a lot of them were critically ill children,” Petesic said.

He added that a common thought is that injuries from fires include burns. “But they were not burned,” he said of the patients.

Most of the patients suffered severe smoke inhalation. “The smoke went up through the stairwell of that building,” he said, “and really caused a lot of people to pass out from carbon monoxide poisoning.”

How Do I Keep Safe at Home?

Petesic said that many of his patients are people of color.

“We see, sometimes, undocumented people,” he said, “because they may not have a carbon monoxide detector in their building.”

Whether you own your home or live in a rental, a carbon monoxide detector can keep you safe from high levels of the noxious gas.

Some health advocates say they’ve experienced negative health effects from even small amounts of poisoning. The National Fire Protection Association stresses that updated research is needed on low-level poisoning, which can lead to impaired brain function including learning and memory, as well as heart problems.

Detectors are a resident’s best bet for staying safe. Some detectors have a two-in-one feature that includes smoke detectors.

Other models are standalone. Some need to be installed in the home. Others can be plugged into a socket or portable system like a transistor radio.

No matter which one you obtain, having them in your home is essential.

“If you have that detector up in your house and you change the batteries twice a year and can check it, most of the time, they’re going to ring,” Petesic said.

Much like a smoke alarm telling you a fire in your home, he said, a carbon monoxide detector will let you know if the fatal gas is present.

Make sure to check the warranty of your detectors. Batteries should be checked twice a year. Detectors can last anywhere from five to 10 years.

New York City has required carbon monoxide detectors in homes since 2004, under the Bloomberg Administration. Five years later, Amanda’s Law required carbon monoxide detectors statewide. (Roxanne Scott/Futuro Investigates)

How to Get —and Maintain— a Detector as a Renter?

If you’re a homeowner, you can purchase detectors and place them in the appropriate places in your home. But according to Census data, two-thirds of New York City residents are renters. Because of the nature of renting, tenants have less control over what appliances they need to ensure they stay safe in their homes.

Building owners are required to provide renters with carbon monoxide alarms, replace expired ones, provide notices about the maintenance of alarms, and inspect heating systems annually. Tenants are responsible for replacing batteries twice a year.

According to the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development, the lack of a carbon monoxide detector in an apartment is a hazardous violation. That means a landlord should fix the issue within 30 days. Fines for building owners range anywhere from $25 to $100, plus $10 per violation per day.

Housing advocates, such as Nori of JustFix, say those fines aren’t enough and that landlords chalk up violations as the price of doing business.

Whatever the housing issue, residents should feel empowered to complain. Advocates such as Nori know that many tenants fear retaliation, such as being kicked out of their apartments. “It’s a really credible fear,” he said.

“The worst crime you could commit is being annoying,” Perez, of VOCAL-NY, said about some renters’ fears about filing a housing complaint

Nori said the byproduct of leaving housing to the whims of the market is that people have to calculate the risks of filing a complaint versus living in an unsafe apartment.

“It’s a tradeoff between healthy housing and affordable housing that should not be made,” he said. “You get what you pay for and that shouldn’t be the guiding principle of housing.”

—

This is the first story in the series “Air We Can’t Grasp: The Insidious Matter of Carbon Monoxide.” It was produced by Futuro Investigates as a project of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 Data Fellowship.

***

Futuro Investigates is the investigative and special projects division of the Pulitzer-winning organization Futuro Media, led by Maria Hinojosa and Peniley Ramírez. Twitter: @fuhinvestigates