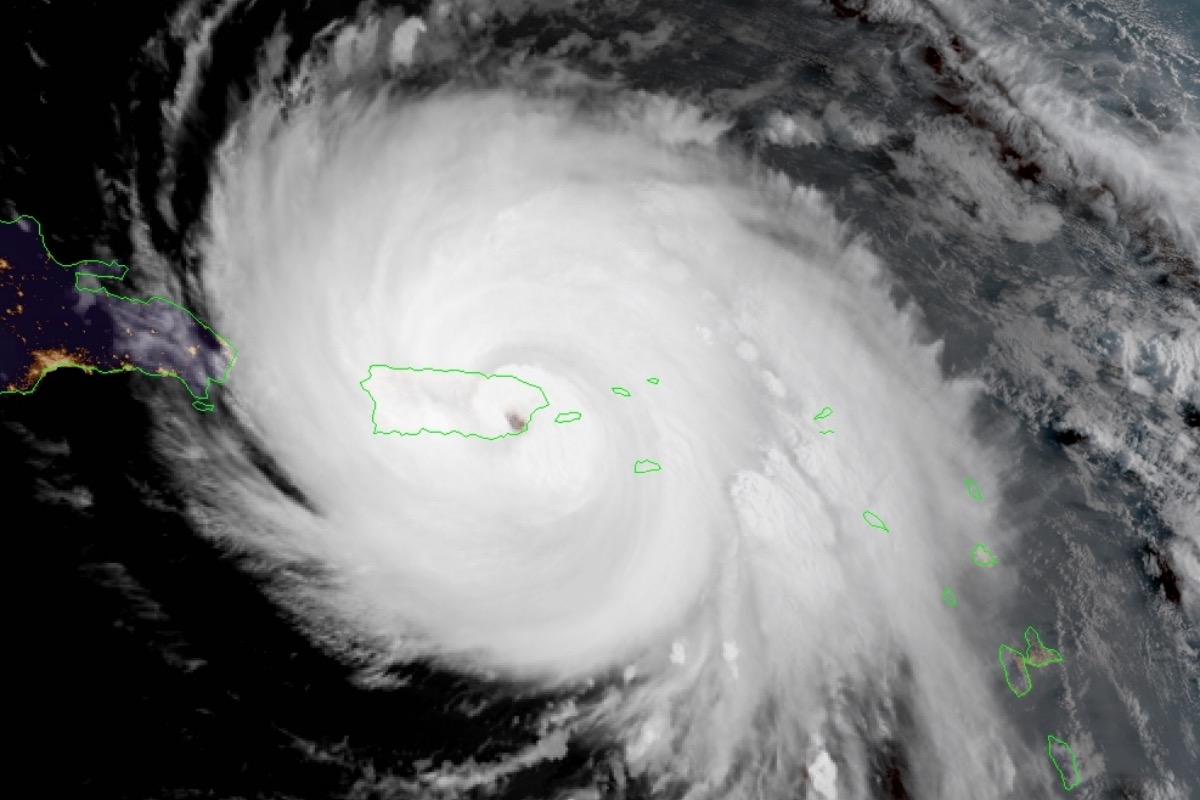

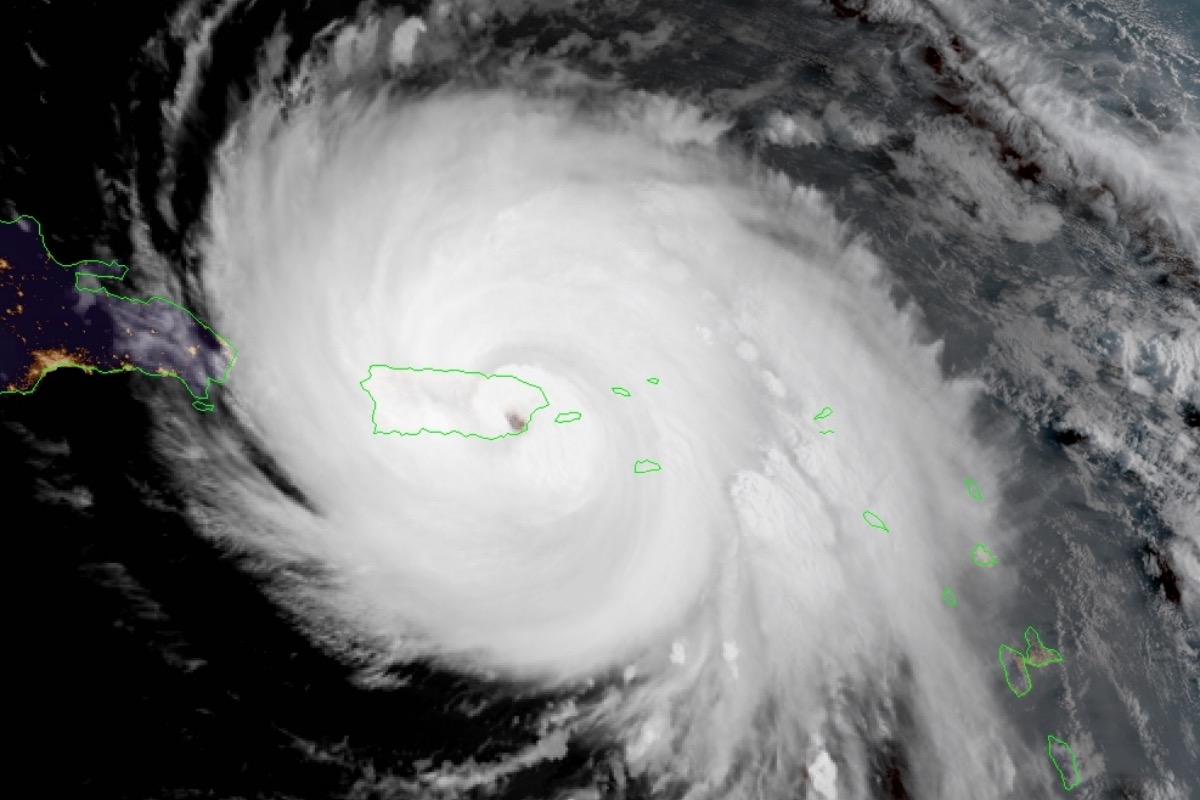

Hurricane María makes landfall near Yabucoa, Puerto Rico, around 6:15 a.m. ET on September 20, 2017. (NOAASatellites/Public Domain Mark 1.0)

SAN JUAN — People from the Caribbean know precisely when hurricane season starts every year. On June 1, they begin seeing the signs they now know by heart: boarded-up windows, long lines at grocery stores, a palpable sense of tension that peaks between August and October, only to ease once the season ends on November 30.

With this year’s hurricane season only a few days away, major forecasters have already made their predictions, most settling on a fairly “normal” 2023 Atlantic hurricane season with an average of 14 named storms, seven hurricanes, and three of those reaching Category 3 or above.

While many are elated to hear that it will be a normal season, experts warn nobody should let their guard down because it could still produce devastating damages caused by destructive winds, heavy rainfall, and flooding.

“All it takes is one storm, one hurricane in the wrong place, and you’ll experience all the effects,” Dr. William Gould, director of the Caribbean Climate Hub at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, told Latino Rebels.

Multiple experts who spoke with Latino Rebels echoed Gould’s sentiment, some warning Puerto Ricans to prepare as if one hurricane was assured to make landfall.

Atlantic hurricane seasons can produce any number of storms, but only one of them needs to make landfall to cause disaster—especially in the Caribbean where damages from multiple seasons can compound alongside other crises.

“Even under these conditions, because of the nature of the region and because the nature of the islands, a tropical storm can do significant damage,” Kristinia Doughorty, a PhD student researching disaster risk management at the University of West Indies in Jamaica, told Latino Rebels.

Hurricane Fiona hit Puerto Rico in September 2022 as a Category 1 storm, causing at least 25 deaths and $2.5 billion in damages. On the eve of Fiona making landfall, the archipelago was still facing problems caused by Hurricane María in 2017, alongside effects from earthquakes, 11 of which were magnitude five or greater. Government mismanagement and corruption made the situation worse.

Many people in Puerto Rico did not adequately prepare for Hurricane Fiona because it was “just a Category 1 hurricane.” Experts say this type of view could cause great harm because it makes people feel safe while being underprepared.

The 2022 Atlantic hurricane season became one of the most costly on record for the United States, mostly because of Hurricane Ian. Peaking at Category 5, it caused damages totaling over $113 billion and killed about 150 people across the United States and Cuba.

Caribbean Uniquely Vulnerable to Increased Storm Activity

The Caribbean is a multi-hazard zone, an area where multiple natural disasters can and regularly do overlap.

Risks outside hurricane season can also exacerbate the damage caused by hurricanes. St. Vincent, a small island country in the Lesser Antilles, suffered an eruption from its largest volcano, La Soufrière, followed by flooding and small earthquakes in April 2021. Over 20,000 people were forced to flee their homes.

“That is three disasters that happened (concurrently). How do you recover? How do you plan for these events? That is something that we in the Caribbean are also trying to consider and grappling with. How do you plan for multiple events at the same time, or if not at the same time, in quick succession?” said Doughorty, who’s also a youth climate activist.

St. Vincent was hit by Hurricane Elsa later in 2021, causing even more flooding and extensive losses to livestock and crops. Approximately a third of the island’s agricultural production had been destroyed by the volcanic eruption earlier in the year.

Hurricanes heavily affect the agriculture and tourism industries, which many Caribbean nations rely on to fund their economies. Such disruptions to local economies can then greatly affect a nation’s ability to respond to natural disasters. Handling multiple disasters at once places strain on government budgets, causing some to put off disaster preparedness in favor of other priorities.

A 2019 UNICEF report found that 761,000 children were internally displaced by storms in the Caribbean between 2014 and 2018, a six-fold increase from the previous five-year period. The report warned that similarly high levels of displacement will likely occur as a result of climate change-fueled storms in coming years.

Climate Change Fuels Risks

“Given climate change has an almost unilateral warming of the surface —that’s more fuel for these storms— we are likely to see a further increase in rainfall,” Dr. Matthew Rosencrans, director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Climate Testbed, explained.

A warmer atmosphere holds more water vapor, which can lead to storms sucking more moisture out of the atmosphere and dumping it across the Caribbean. The latest NOAA fact sheet concludes that it is likely that hurricanes will be more intense globally and have higher rainfall rates. The maximum intensity of Atlantic hurricanes is likely to increase by about five percent throughout the 21st century.

However, researchers have also found that historic data at the current moment does not provide compelling evidence that climate change will change the frequency of storms or the proportion of hurricanes that become major hurricanes.

Data also points to an increasing trend in rapid intensification rates for hurricanes. As the ocean warms, hurricanes speed up dramatically. One study found a large number of storms experienced “extreme rapid intensification“ between 1990 and 2021.

But climate change has also caused some storms to weaken more slowly once they hit land, which causes more rainfall wherever they hit.

Sea level rise also causes an increase in coastal flooding, which could greatly affect population centers built at or below sea level. Georgetown, the capital of Guyana, was built nearly six feet below sea level but is protected by a 280-mile sea wall and a series of canals. Even still, the city of 240,000 habitually floods and is predicted to be underwater by 2030.

Predictably Unpredictable Hurricane Seasons

While many major institutions forecasted a normal or near-normal season, some predicted a below-average or above-average season. Colorado State University predicted a slightly below-average season, while the University of Arizona predicted a very active hurricane season.

This year will be “closer to 2017 compared to (2022),” said Dr. Xubin Zeng, director of the Climate Dynamics and Hydrometeorology Center at the University of Arizona.

Part of the reason for the differing predictions can be attributed to competing atmospheric conditions, explained Rosencrans, who is also the lead NOAA hurricane forecaster. El Niño, a complex series of climatic changes that result in unusually warm waters, is developing in the Pacific. Meanwhile, record-setting sea surface temperatures are warming in the Atlantic. At the moment it’s unclear which factor will become prevalent or if they will cancel each other out, causing a stronger hurricane season.

These conditions are “unprecedented,” according to the Weather Underground.

There is not a lot of historical data they can look at to better understand this upcoming season, Rosencrans explained. But NOAA’s prediction factored this uncertainty into their forecast, which is why their certainty is not as high as in previous years. They forecasted a 40 percent chance for a “near normal” season, with a 30 percent chance for an above or below-average season.

Seasonal forecasting is tricky business, which is why many institutions update their forecasts later in the year when they have more data and are closer to the peak hurricane season.

Preparedness is Key

“(In 2022), there were 14 named storms. But Fiona—the other 13 did not matter. It only took the one. So be prepared as if one is going to hit you every year,” Rosencrans said.

Multiple experts agreed that the key to riding out hurricane season safely is being as prepared as possible regardless of predictions. Many advise to prepare as if at least one hurricane were going to make landfall, then if it does not happen, to keep supplies ready for the next year.

“One of the big lessons from the 2017 hurricanes was that after the storm passed, there are still implications and complications due to the effects on infrastructure and communication and transportation,” said Gould.

Hazards such as flooding, downed electrical cables or lack of access to electricity can greatly affect health and safety in the aftermath of a hurricane. Experts particularly stressed access to information may be cut off after a hurricane, so residents should make sure to have more than one way to communicate with others, like a phone, radio or computer.

“Get the supplies ready now while it is quiet,” Rosencrans said, urging people to check government websites to assure that they are prepared for any coming storms.

***

Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco is the Caribbean correspondent for Latino Rebels, based in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Twitter: @Vaquero2XL

nice