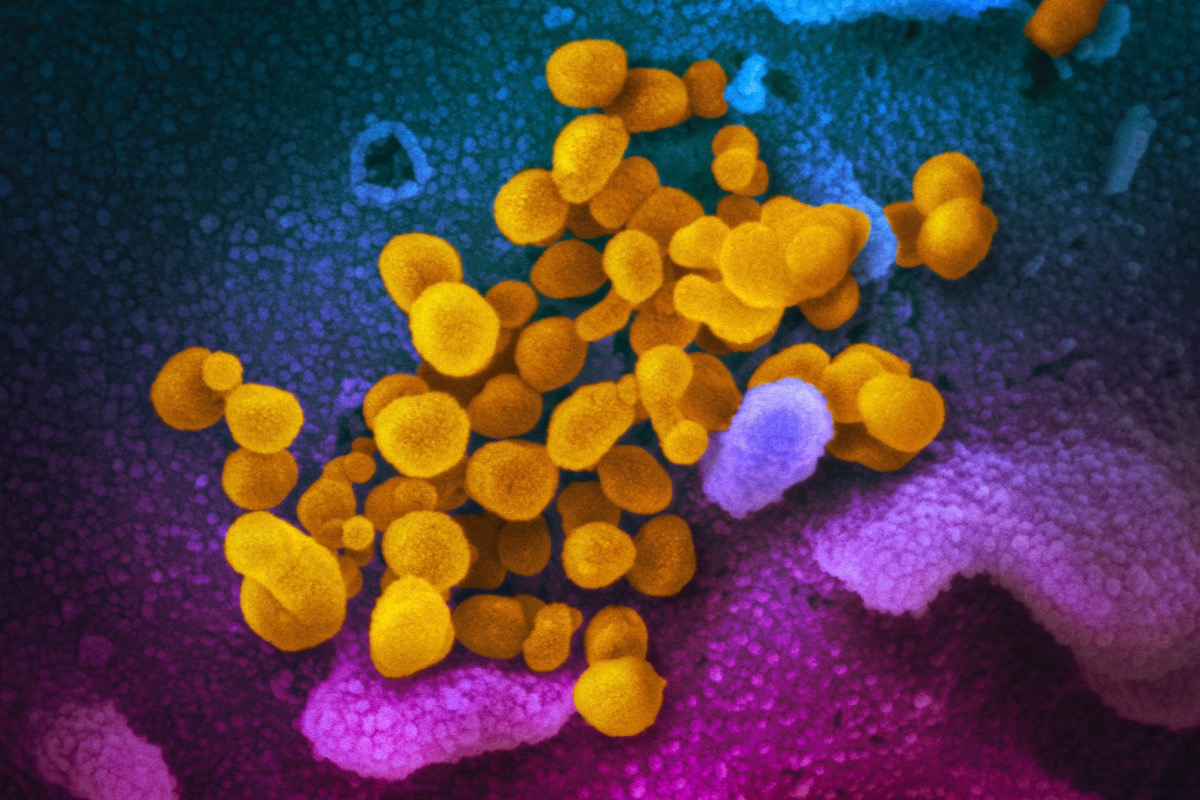

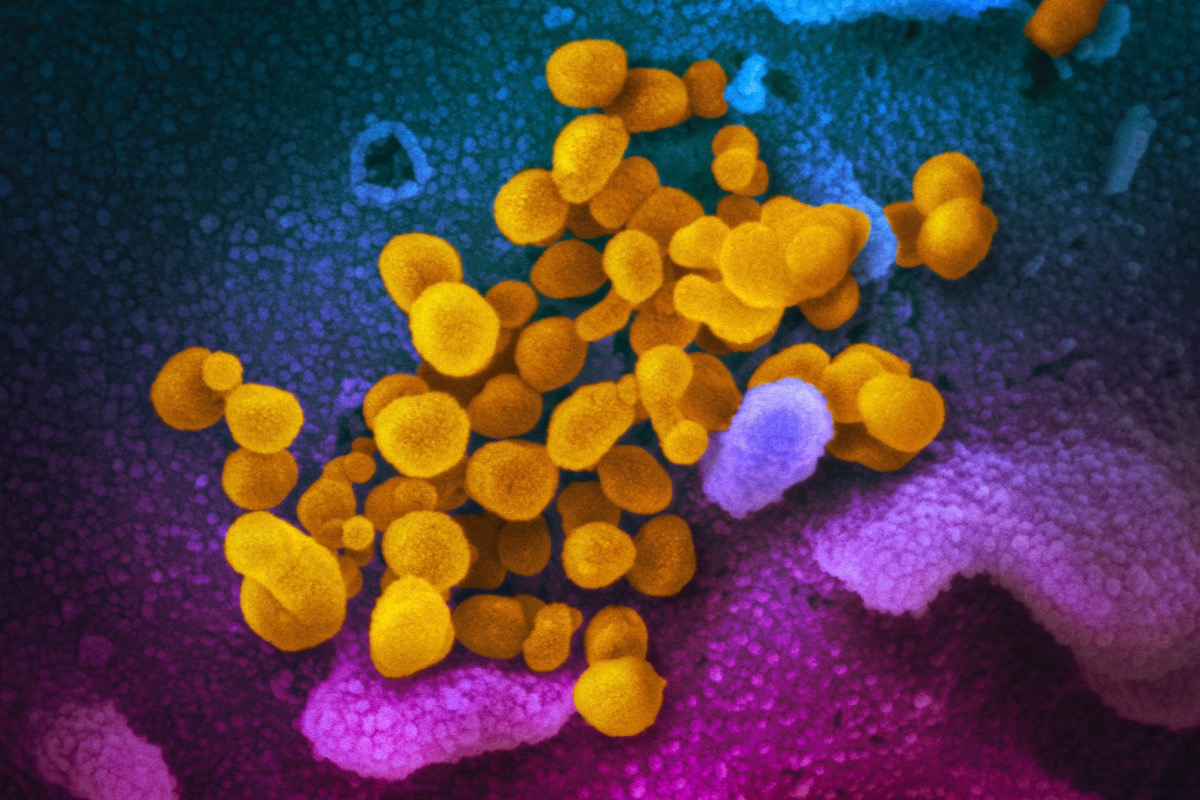

This undated, colorized electron microscope image made available by the U.S. National Institutes of Health in February 2020 shows the Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, indicated in yellow, emerging from the surface of cells, indicated in blue/pink, cultured in a laboratory. (NIAID-RML via AP)

When Karla Monterroso got sick with COVID-19 in March 2020, she initially thought she was imagining her symptoms. The virus was all over the news, and Monterroso chalked up her sudden tiredness and worsening cough to pandemic-induced hypochondria. Then her temperature surged into the triple digits and refused to go down, leaving Monterroso bedridden for two full months.

“It was unrelenting fever,” said Monterroso, a California native who led a nonprofit seeking to increase Black and Latino representation in the tech industry. “I had to crawl from room to room (in my apartment) because walking was so debilitating.”

Three years later Monterroso still hasn’t recovered from her initial bout with COVID. She suffers from chronic fatigue that hinders her ability to perform simple tasks, and movements as basic as standing up can cause her heart rate to spike dangerously. The drastic change in her health has forced her to leave the nonprofit and transition to part-time consulting work.

Monterroso is one of the millions of Americans whose lives have been upended by long COVID, an assortment of symptoms and medical problems that persist for weeks, months, or even years after an initial infection. Growing evidence suggests long COVID is especially common among Latinos, a group disproportionately affected by the pandemic and its economic fallout.

The presence of long COVID in Latino communities —coupled with a lack of awareness about the condition and limited options for treatment— is deeply worrisome to Monterroso.

“There are people out there right now who are waking up fully depleted in a way that they don’t understand,” she said. “They have no idea that what’s happening to them is long COVID.”

A Worrying Trend

Much remains unknown about long COVID and its underlying causes. The dizzying array of symptoms associated with the condition —including exhaustion, brain fog, respiratory and cardiovascular issues, and neurological problems— has made it difficult to treat or quantify, and scientists are still working to understand why it affects some COVID-19 survivors and not others.

A series of studies from the past two years point to long COVID’s outsize toll on Latino Americans. In a nationwide survey released in May by the U.S. Census Bureau, 36 percent of Latino respondents reported COVID-19 symptoms lasting three months or longer, compared with 31.8 percent of Black respondents and 30 percent of whites. Earlier research from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that nine percent of Latino adults had long COVID—higher than Black and white adults and nearly double the percentage of Asian adults.

Long COVID’s prevalence among Latinos is a troubling but unsurprising outcome of the pandemic, which saw people of color hospitalized and die at higher rates than the general population, medical experts told Latino Rebels. One factor is the fact that Latinos are overrepresented in the nation’s “essential workforce” and more likely to live in crowded, multi-generational households, which made COVID harder to avoid when it first began spreading.

“Many had jobs that got them infected God knows how many times,” said Dr. Viju Jacob, the medical director at Urban Health Plan, which operates community health centers in underserved New York City neighborhoods. “And each time you have an infection, you’re more likely to have long-term consequences.”

Jacob also highlighted the large number of Latinos infected by early strains of the virus, which have been linked to a higher likelihood of developing lasting COVID symptoms. He also warned that the heavy concentration of long COVID cases in communities of color could compound existing health inequities and force families to make difficult decisions around treatment.

“Many of our patients are going to face dilemmas like, ‘How am I going to pay for my diabetes medicine?’” while managing long COVID costs, he said. “It’s a truly sad situation.”

Barriers to Treatment

People with long COVID face many obstacles to accessing care, but getting a correct diagnosis can be a battle in itself.

Angela Vázquez made a series of trips to the emergency room in the spring of 2020. Vázquez had contracted COVID-19 earlier that year, and her symptoms had worsened dramatically in the weeks that followed. When she visited the ER complaining of body numbness and disorientation, medical staff attributed the symptoms to anxiety over the pandemic.

“I went to the hospital multiple days in a row and… didn’t even get lab work done,” said Vázquez, who works for a children’s health equity nonprofit in Southern California. “I was coded as a Brown woman having a psychiatric crisis and then discharged.”

Vázquez was able to find some validation from a friend, who encouraged her to seek out physicians specializing in illness triggered by infection. She switched primary care providers and finally received confirmation that her symptoms were a result of COVID-19.

“People have been getting post-viral chronic illness for generations, and that’s the kind of medical information that’s not out there, especially in immigrant communities and communities of color,” Vázquez said.

The dearth of information on long COVID in Latino communities may be keeping Latinos with lingering symptoms from seeking treatment, according to medical experts. Other well-established barriers to care, including high costs, limited English proficiency, and problems navigating the nation’s medical system, could also be deterrents.

“I don’t think many people in the Latino community are aware of the fact that the reason they don’t feel well is because they have long COVID,” said Dr. Leo Morales, a professor at the University of Washington School of Medicine and co-director of UW’s Latino Center for Health. “There’s a burden of disease out there that is not well recognized.”

To better understand that burden, Morales is conducting a study on long COVID’s prevalence and impact among Latinos in Washington state. Preliminary results are expected in October.

Morales hopes the study will further illustrate long COVID’s toll on Latino communities and encourage clinicians to take ongoing symptoms seriously.

“I think just shedding that light will raise the profile of the problem,” he said. “There’s much more that needs to be done in terms of equipping primary care doctors to recognize (long COVID) and then to provide treatment themselves.)

Planning Ahead

Three years after the onset of the pandemic, long COVID has become a talking point in and outside medical circles. The condition was formally defined by the World Health Organization in October 2021, and multiple governments have launched large-scale studies aimed at understanding its effects.

In the U.S., long COVID can be considered a disability under certain circumstances, creating a pathway for patients to receive disability insurance and other federal support.

Still, the country remains unprepared to assist the growing number of Latinos with long-term COVID symptoms—some of whom may be unable to work or fulfill other responsibilities, advocates and physicians told Latino Rebels.

“I worry most about the impact this is having on families,” Dr. Morales said. “It’s not just severely ill patients who aren’t able to work, but also parents who can’t keep up with caregiving activities.”

Monterroso highlighted the need for “culturally responsive” outreach and resources, noting that most long COVID support services cater primarily to white patients. She also called on lawmakers to make federal disability benefits more accessible to Latino patients.

“I think the focus among long COVID patients is often about diagnosis and treatment, which are both important,” she said. “But the missing gap for many people of color is support and care, because we’re denied disability (insurance) at a different rate.”

Monterroso has grown tired of convincing providers that her chronic exhaustion and elevated heart rate stem from a previous COVID-19 infection. She worries other Latino sufferers of long COVID will remain untreated so long as they continue to be dismissed by medical professionals.

“The average person of color is interacting with health care in a way that is tremendously adversarial,” she said. “They’re either getting ignored by the system or they’re seen as disrespectful just for advocating for themselves.”

***

Illan Martin Ireland is a summer correspondent at Futuro Media and a graduate of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

In the US Long Covid is considered a disability. And there you have it. Smh

[…] Jason Aldean? Please spare me the small-town nostalgia. Gradus ad Parnassum, or, Stepping up to Lev Long COVID a Growing Threat to Latino Communities Here’s the real problem with Florida’s school standards for slavery My 43-Minute Reaction to […]