The good news is that I was right.

The bad news is structural oppression.

I hacked the imagination of French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu.

I think all of us Chicanos did. I was doing it since I was a child, from the first moment I began translating for my parents.

That was my first job—translating the outside world into Spanish for my mom and dad.

I don’t even remember when I began doing it. I simply remember language as that power. It made me equal to adults.

And there was something wrong with that. Yet, I could not put that into words. And I did not have time to put it into words because I had to act. If I did not act, my family did not act.

We were one of the first Mexican, and I suppose I made us, Mexican American families in our neighborhood on the South Side of Chicago. And I knew if we did not take action, we would be crushed. I was not going to let us get crushed.

If I could pull my weight, and then some, just a little more, my dad easily carried the rest, and my mom smoothed out the rough edges. We would survive, and some day, and some days, or at least for a few hours, thrive.

I was a Cultural Accelerator. I had not coined the phrase for it yet. But it was formulating inside me, through me, because of me. And it helped me survive until I could thrive by uttering the phrase.

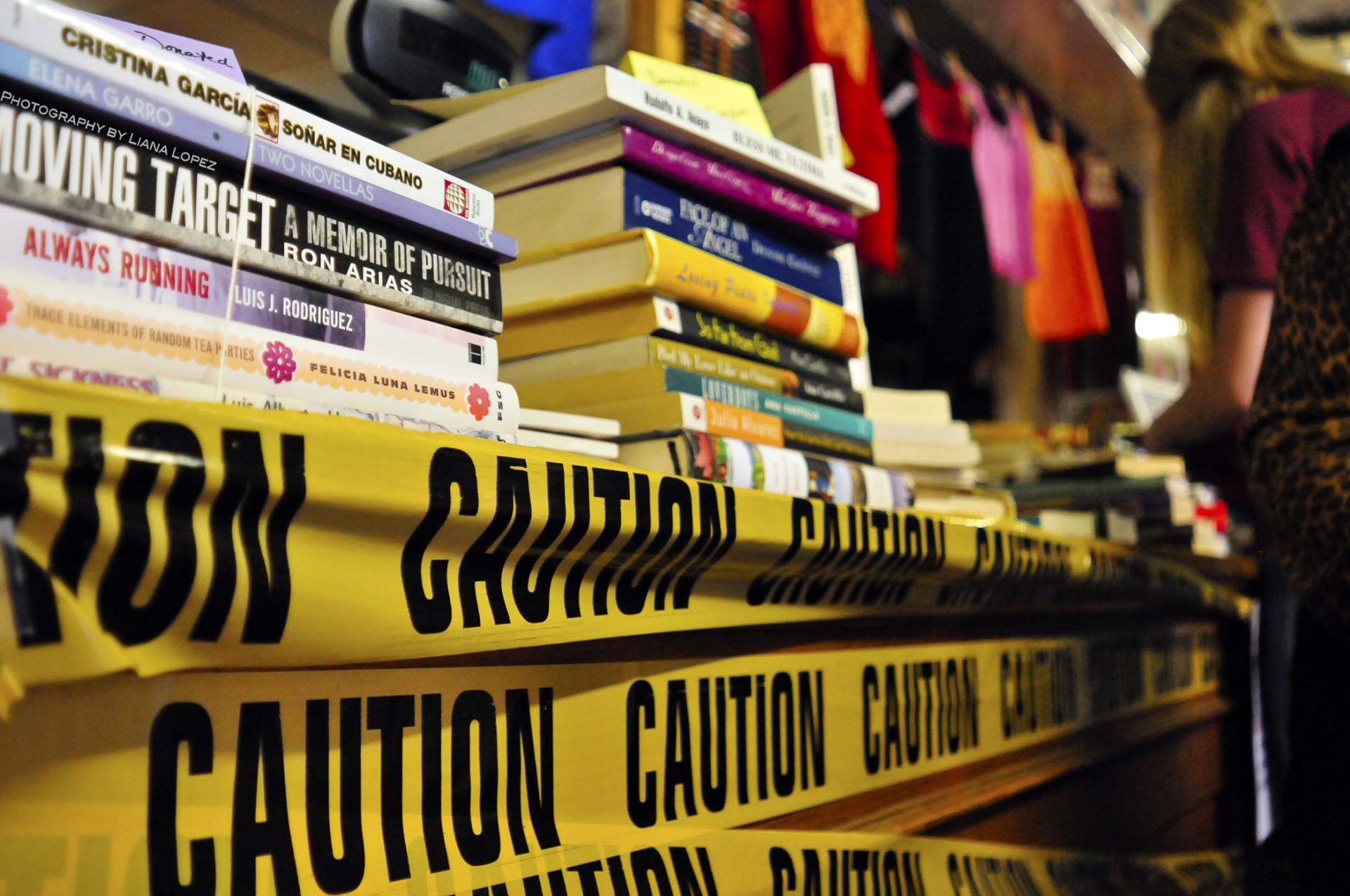

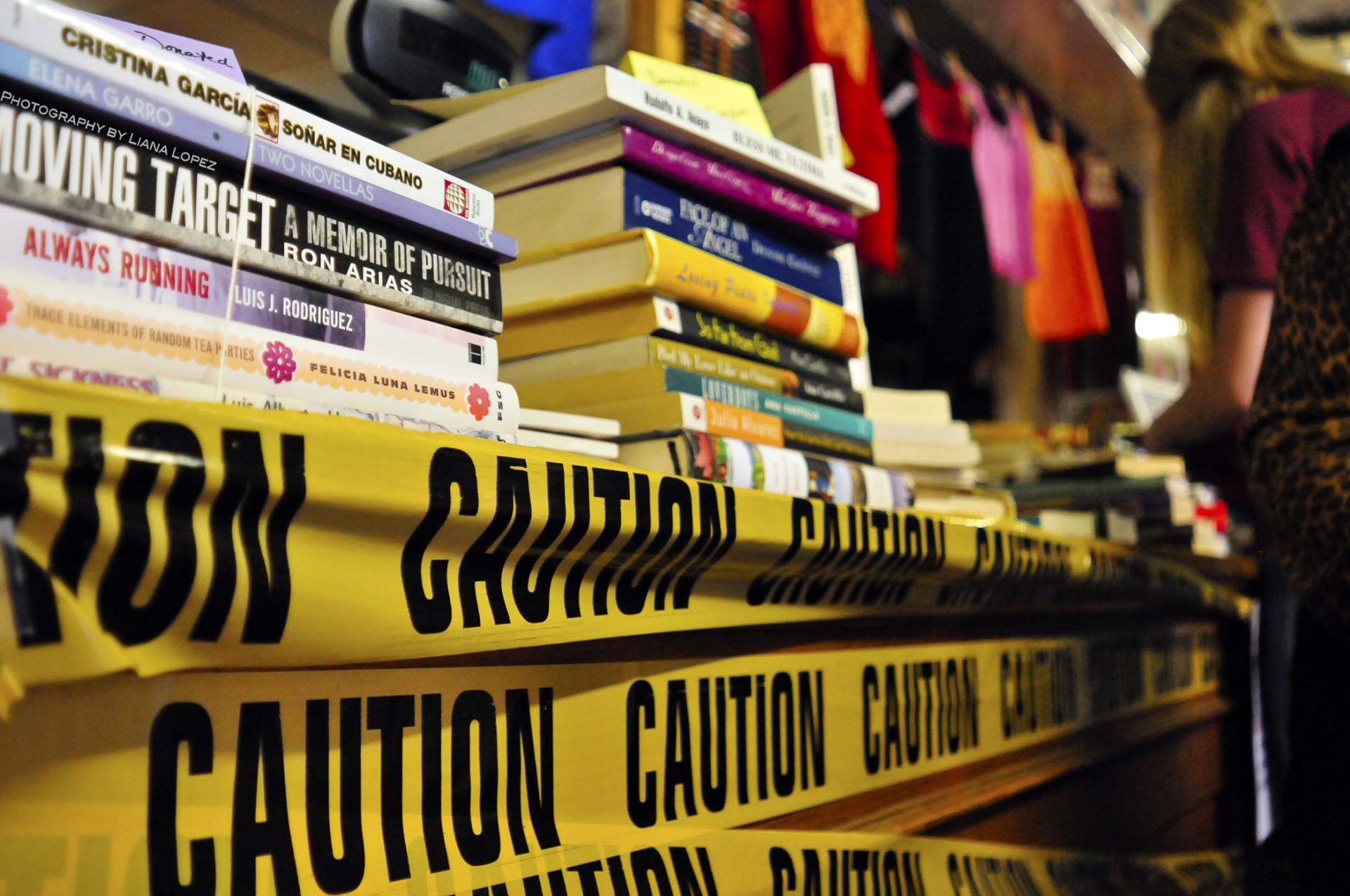

Chicana, Chicano, and Latino authors helped me survive the educational, work, and political system to get me to the exacting wording of my struggle. They lived it and described and discussed it is so clearly to me.

Yet, other folks still not understand.

Again, it was like translating. You can convey some literal explanations, but there are more profound ones that will escape the target of your words. The persons you are speaking to might even ignore the profound message even when it registers. Or, most likely, they have turned their minds off to you saying, thinking, or imagining, anything of importance except to report if you will or have fulfilled their desires.

Of course, they would listen to a white man, especially if he spoke French.

When I first read Pierre Bourdieu’s work, I was as thrilled as when I first read Gloria Anzaldua’s work, or Dagoberto Gilb’s fiction, or Piri Thomas’ novel Down These Mean Streets.

They struck a profound tuning fork. I felt that intellectual buzz of matching profound deep ideas.

The first novel written by a Latino that I read was Thomas’ novel. He was a Puerto Rican writer from NYC. I was a Chicano on the South Side of Chicago, but I could relate to the chaos, violence, the Spanglish, the cursing, the struggle, the writing. It boggled my mind. Finally, as a Junior in college, I was reading sentences that worked at a literal level, a social level, cultural, spiritual, level.

My Creative Writing teacher had turned me on to it. No one else read it. When I read it to others, they did not get it. It was not taught at my college, my high school, and well, it was probably too intense for middle school.

I was a one-man island of the literature of one man from The Island. But that was more, because before that I was the only one in my head.

I was not a nobody. I was only body.

Now, I was mind and imagination. I was not crazy to think. My body carried a brain, and that brain was calling the shots. That brain was the boss. Not my fist, my kick, or my.

Thirty-five years later, I would have the same experience reading Pierre Bourdieu’s Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, finding his work on my own, then more, then more.

His breakdown of the sociology of cultural breakdown and build-up was the stuff of Chicana, Chicano, and Latinx fiction, poetry, and memoir and our own sociologists.

Again, his translated French was saying in English what we had been saying slightly differently in Spanglish.

I remember his discussion of the structural oppression of Moroccans in France. Their plight was familiar. It dawned on me that everything he observed about Moroccans in France could be applied to Chicanos in the U.S. And then it struck me.

Here’s the bad news.

He studied structural oppression.

My family dramatized it.

He conducted surveys to quantify it.

We conducted protests.

He summarized.

We survived.

The rage is that we are saying the same thing. To our ears. Seems obvious. But his work puts it in terms Anglo folks understand from a white fellow who speaks French.

Don’t stereotype me as bitter. Because now, because of him, we are allies.

He quantified in numbers.

We quantified in blood.

So, I was right. When I was a kid on the south side of Chicago, I knew I was surrounded by rackets, at every level, but I could not put it into words. However, I could find the words to act. I had to. That was my job.

Again, my first job was translating the outside world into Spanish for my parents. That made me equal to adults.

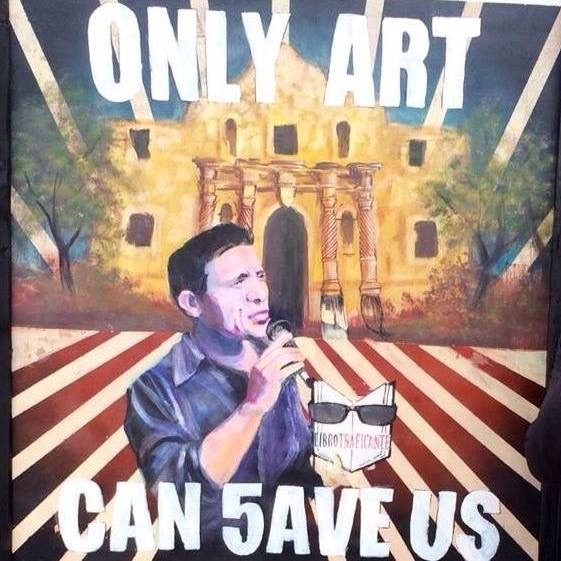

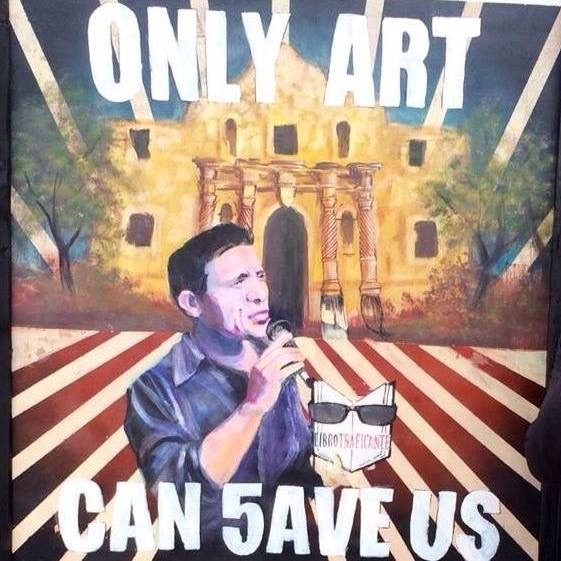

Now as an adult, as a Cultural Accelerator, I translate our world into English, so others can understand us. That makes us equal to you.

I may have gotten to the books at a disadvantage, but my family’s Cultural Capital multiplied the power of the educational capital they helped me obtain. And I was delivered to this era of upheaval by a community used to upheaval, so that everything that once simply helped us survive will now help us thrive. And I can act on that knowledge.

And I can finally put into words the blessing that will benefit my community and unite us with your community: I am a Cultural Accelerator.

***

Tony Diaz is a writer, activist, professor and media personality. More at TonyDiaz.net. He tweets from @Librotraficante.