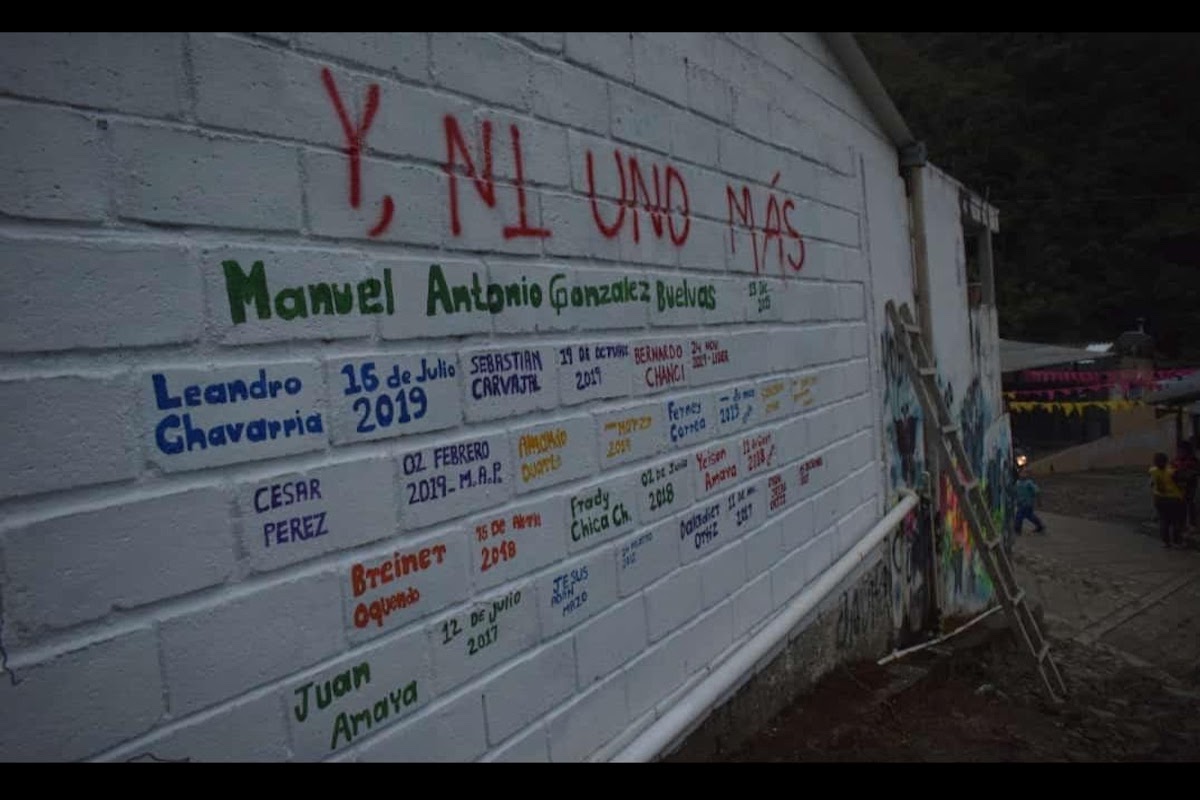

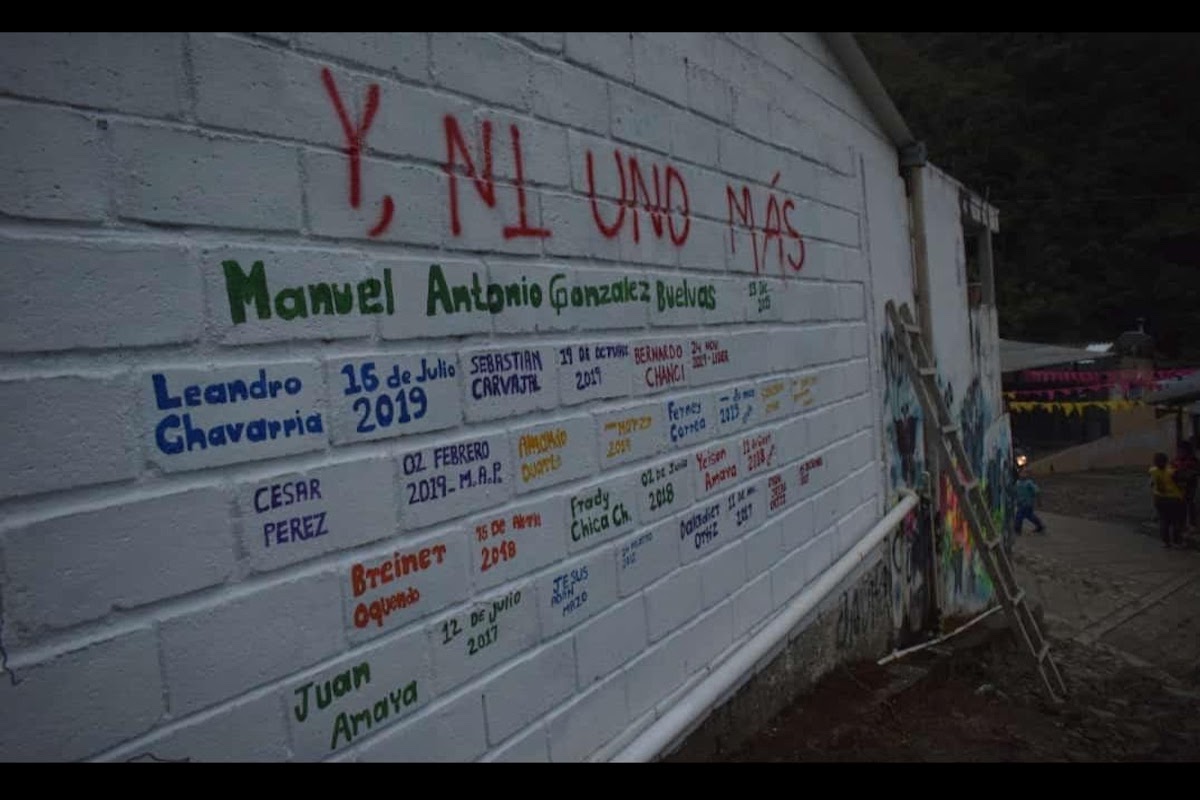

The Santa Lucía community painted a mural with the names of murdered friends and family. (Photo by John Taborda)

By Nicolás Bedoya

On Tuesday, the rural community of Santa Lucía in northern Colombia held a ceremony to grieve the death of another ex-combatant. Manuel González was the 180th FARC guerrilla member to be killed in Colombia since the signing of a peace accord in 2016 between the rebel group and the government.

González joined the FARC guerrillas when he was 15 years old. The peace deal gave him a shot at a “normal” civilian life after 14 years fighting the government deep in the jungle. He settled down in Santa Lucía where he was undergoing the reintegration process. The small rural hamlet hosts a territorial training and reintegration camp for over 70 former guerrilla fighters of the FARC. They are part of the 7,000 ex-combatants who demobilized and turned over their weapons to the United Nations.

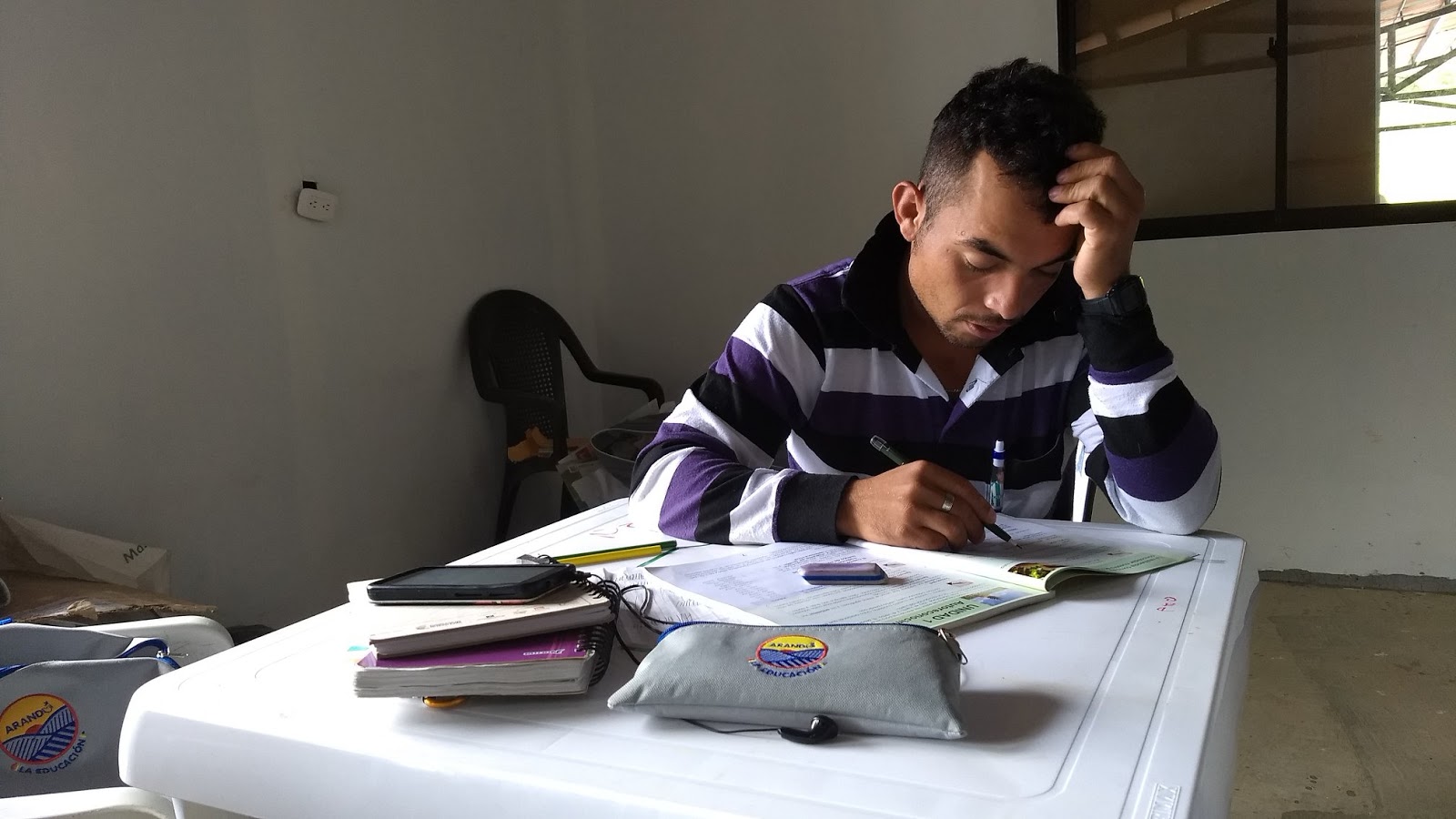

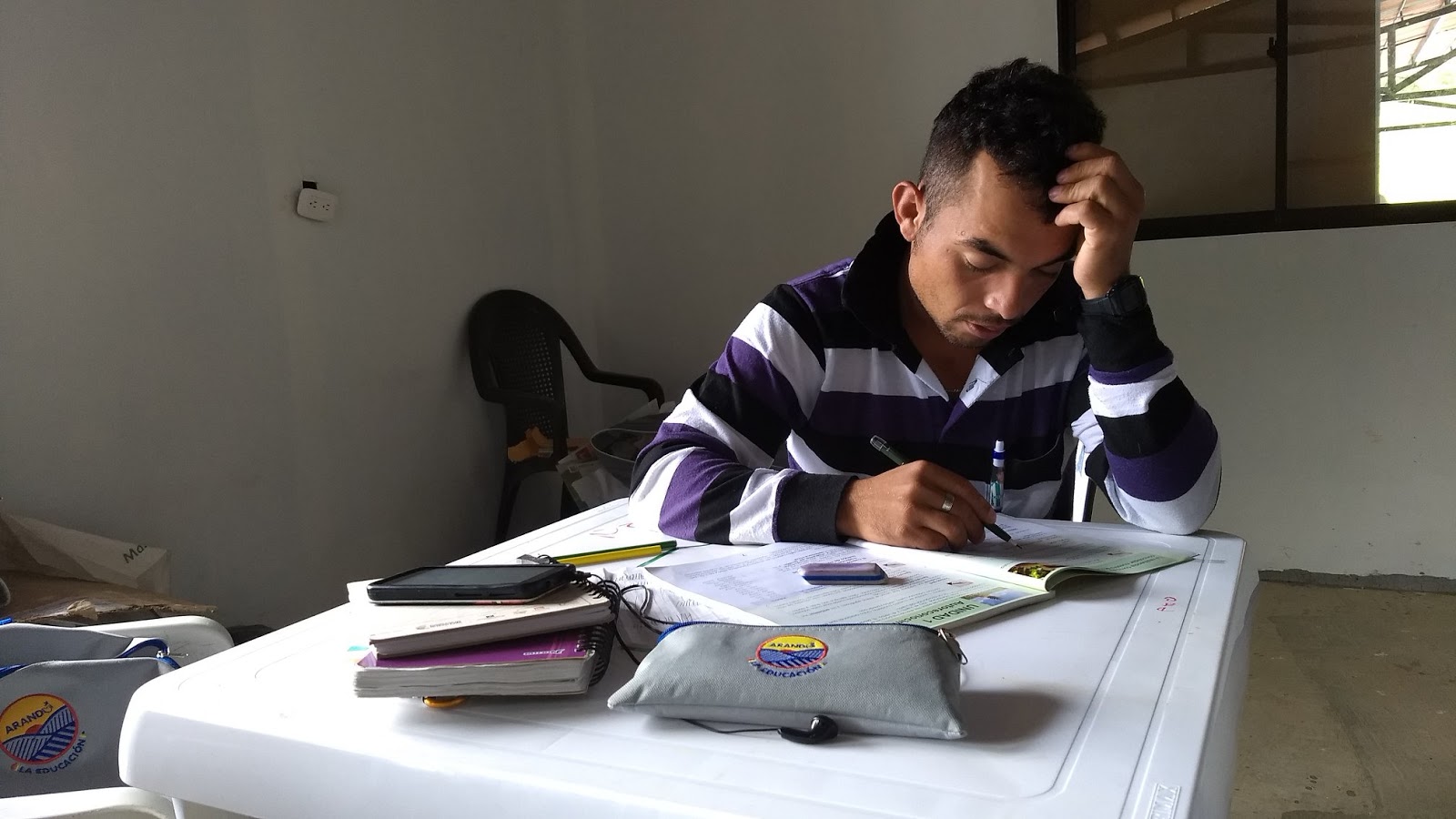

At the camp, González learned to read and write, taking advantage of educational opportunities denied to him during years of armed conflict. In February, González’s wife gave birth to a baby girl. He supported his family working in a collective cattle project and as a motorcycle taxi driver.

Last Friday around 1 p.m., González got a request to take a passenger to the small town of Ituango—an hour and a half away on his motorcycle. On the journey back, he was stopped by armed men just 40 minutes from the camp. González was forced to lay face down on the ground, and he was executed. Following his death, the FARC released a statement condemning the warning left by the armed group: “any ex-combatant seen transiting the road today will be killed.”

Franklin, a friend of González’s and fellow ex-combatant living in Santa Lucía who goes by an alias, said he found out about González’s death about three hours after it happened.

Manuel González learned to read and write in the Santa Lucía reintegration camp. (Photo by Viviana Vargas)

“Here you can’t move at night,” Franklin said over the phone. Armed groups had imposed a curfew preventing any movement on rural roads past sunset. “It was hard because authorities wouldn’t retrieve the body.”

Despite the fear and danger of violating the curfew, the community refused to leave González’s body on the road. “Out of the pain and impotence we all felt, 14 of us decided to go pick him up and bring him to the camp,” Franklin said.

The community waited until the next morning for authorities and crime scene investigators to arrive at the camp and take the body. However, faith in government security forces hangs by a thread in this region. Ituango, the municipality where Santa Lucía is located, boasted one of the highest homicide rates in Colombia in 2018, and 11 ex-combatants have been killed there since the signing of the peace accord.

Thirty years after armed groups began operating in Ituango, the area once again became a conflict zone at the end of 2017. The government proved ineffective in preventing narco paramilitary groups from taking over former FARC territories. Paramilitary offensives in former rebel territory have led to a rise in the number of guerrillas choosing to rearm to combat their old nemesis.

“Ituango has taken the worst of this peace process by far,” commented one woman who was forced to leave her hometown last year. She didn’t want to provide her name for safety reasons. In November alone, fighting between FARC dissidents and the Clan del Golfo paramilitary group displaced over 200 people in the municipality.

However, it is not only ex-combatants who have been targeted. In the last three years, over 700 social leaders have been killed too. Bernardo Chancí, a community leader who promoted the government’s voluntary substitution of coca crops, was assassinated in Ituango just 20 days before González was killed. The police also “accidently” shot social leader Ferney Piedrahita outside his home last month without warning, allegedly mistaking him for a combatant.

“The implementation of the peace process requires very delicate leadership,” Franklin said. “Any loss of an ex-combatant or social leader is an attack on the peace process. Unfortunately, us Colombians have gotten used to getting killed. We pick up the dead and bury them, we pick them up and bury them again. Nothing changes.”

Many fear the new FARC political party, whose leaders are mostly ex-combatants, will share the fate of the Patriotic Union political party, which was born out of peace negotiations in 1985. Throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s, over 2,000 of its members and politicians were systematically assassinated by security forces and paramilitaries. Many ex-combatants say this is already becoming true of the FARC. Elmer Arrieta, González’s father, has received multiple death threats. Arrieta recently ran for the departmental assembly as a candidate for the FARC political party. Before the peace process, he was the second in command of the FARC front that operated in Ituango.

“Today they took my son, but not just from me,” Arrieta said at his son’s burial on Tuesday. “They took him from the people, from peace and from the hope that reconciliation will prevail. Peace should not cost us our lives.”

At the end of the ceremony, the Santa Lucía community painted a mural listing the names of their dead loved ones at the entrance of the hamlet. With the situation growing more tense by the day, the sobering list is only expected to get longer.

***

Nicolás Bedoya is a photographer and researcher specializing in social conflicts and human rights. He is the cofounder of Colombia-based VELA Collective and has been featured on BBC, Bloomberg, America’s Quarterly Magazine and others. VELA’s work uncovering the guerrilla dissident phenomena and paramilitary incursions in northern Colombia forced him to leave the country in 2018. Nicolas now resides and works in New York.